In the field of precision mechanical transmission, the harmonic drive gear stands out as a pivotal technology due to its exceptional characteristics such as high reduction ratios, compact size, and superior positional accuracy. Since its inception in the mid-20th century, the harmonic drive gear has found widespread applications in robotics, aerospace systems, and precision instrumentation. The core of its performance lies in the meshing behavior between the flexspline and circular spline, which is profoundly influenced by the tooth profile geometry. Among various profiles, the double-circular-arc tooth profile, comprising two circular arcs connected by a common tangent, has garnered significant attention for its potential to enhance load distribution and reduce stress concentrations. However, traditional design methodologies, particularly the unidirectional conjugate method, face inherent limitations in ensuring conjugate engagement across the entire profile, especially for the convex arc segment of the circular spline. This uncertainty can lead to suboptimal contact conditions, reduced meshing area, and increased wear. In this article, I present a novel bidirectional conjugate design method that addresses these shortcomings by jointly considering the conjugate relationships of both the flexspline and circular spline profiles. This approach not only resolves the ambiguity in the circular spline’s convex arc but also promotes multi-point contact, larger engagement areas, and lower contact stresses, thereby advancing the performance of harmonic drive gears.

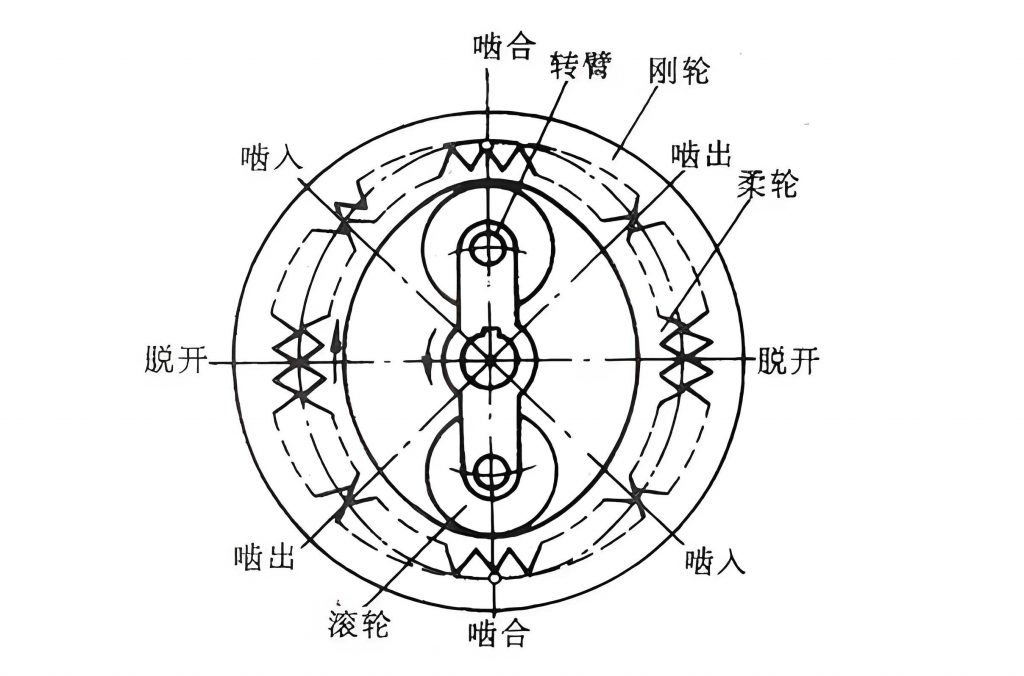

The harmonic drive gear operates on the principle of elastic deformation: a wave generator deforms a flexible flexspline, which then meshes with a rigid circular spline to achieve motion transmission. The tooth profile is critical in determining the quality of this meshing action. Early designs employed straight or involute profiles, but these were gradually superseded by more sophisticated shapes like the “S-tooth” profile and the double-circular-arc profile. The double-circular-arc profile, as the name suggests, consists of two distinct circular arc segments on each tooth: a convex arc near the tooth tip and a concave arc near the tooth root, smoothly joined by a tangent line. This configuration aims to provide continuous conjugate contact over a broader range, improving torque capacity and longevity. However, designing such a profile for harmonic drive gears is non-trivial due to the complex kinematics involving variable deformation of the flexspline. The prevalent unidirectional conjugate method, which derives the circular spline profile from a preset flexspline convex arc, often results in an indeterminate conjugate profile for the circular spline’s convex arc segment. This can lead to scenarios like double conjugation, secondary conjugation, or even profile crossover, which compromise meshing smoothness and efficiency. Therefore, a more integrated design approach is warranted to harness the full potential of the double-circular-arc tooth profile in harmonic drive gears.

Our proposed bidirectional conjugate method fundamentally rethinks the design process by incorporating a reverse conjugate calculation from the circular spline back to the flexspline. This ensures that both arcs of the flexspline are conjugate with the circular spline’s convex arc, eliminating the uncertainty inherent in prior methods. The workflow begins with parameter presets for the flexspline’s convex arc, proceeds through conjugate calculations to obtain the circular spline’s double-circular-arc profile, and then performs a reverse conjugation to derive the flexspline’s concave arc. By fitting conjugate points to circular arcs and ensuring non-interference, the method yields complete tooth profiles for both components. This holistic approach reduces the number of required design variables and enhances the robustness of the harmonic drive gear design. In the following sections, I will elaborate on the mathematical foundations, step-by-step procedures, and analytical validations of this method, demonstrating its superiority through comprehensive case studies and finite element simulations.

To establish a rigorous framework for the bidirectional conjugate design method, we first define the coordinate systems and geometric relationships governing the harmonic drive gear assembly. Under standard assumptions—such as inextensibility of the neutral curve, equidistant curve deformation, and rigid tooth profiles—we model the meshing in a plane. Let us consider three coordinate systems: the wave generator frame {OXY}, the flexspline tooth frame {o1x1y1}, and the circular spline frame {o2x2y2}. The deformed neutral curve of the flexspline is described by its radial displacement ω(φ) from the initial radius rm, where φ is the angular position relative to the wave generator’s major axis. The neutral curve radius before deformation is given by:

$$ r_m = \frac{D_b + \delta_f}{2} $$

where Db is the outer diameter of the flexible bearing and δf is the wall thickness at the flexspline tooth root. The position vector of the deformed neutral curve is:

$$ \rho(\phi) = r_m + \omega(\phi) $$

The circumferential displacement υ and the normal rotation angle μ of the neutral layer are derived from the radial displacement as:

$$ \upsilon = -\int \omega \, d\phi $$

$$ \mu = -\arctan\left(\frac{\dot{\rho}}{\rho}\right) $$

Here, the dot denotes differentiation with respect to φ. The angular positions are then related by:

$$ \phi_1 = \phi + \frac{\upsilon}{r_m} $$

$$ \phi_2 = \left(\frac{z_1}{z_2}\right) \phi $$

$$ \gamma = \phi_1 – \phi_2 $$

$$ \Psi = \mu + \gamma $$

where φ1 is the rotation angle of the deformed flexspline end, φ2 is the rotation angle of the circular spline, z1 and z2 are the numbers of teeth on the flexspline and circular spline respectively, γ is the angular difference between them, and Ψ is the angle between the y-axes of the flexspline and circular spline frames. These relationships form the kinematic basis for subsequent conjugate calculations in the harmonic drive gear.

The bidirectional conjugate design method unfolds in a systematic sequence, as illustrated in the flowchart below. We commence by presetting key parameters for the flexspline’s convex arc. Essential design variables include the module m, tooth numbers z1 and z2, radial deformation coefficient ω0*, bearing outer diameter Db, wall thickness δf, and various height coefficients. Additionally, we define the tooth thickness ratio K, flexspline addendum height ha1, flexspline dedendum height hf1, circular spline addendum height ha2, circular spline dedendum height hf2, working height hl for the convex arc, and the arc inclination angle β. These presets are crucial for tailoring the harmonic drive gear to specific applications.

With the parameters set, we compute the flexspline convex arc. The flexspline pitch diameter d1 is:

$$ d_1 = D_b + 2\delta_f + 2h_{f1} $$

The pitch tooth thickness Sa is:

$$ S_a = \frac{\pi d_1}{(1+K) z_1} $$

The radius of the convex arc ρa is:

$$ \rho_a = \frac{h_{a1} – h_l}{\sin \beta} $$

The distance from the arc center to the tooth symmetry axis la is:

$$ l_a = \frac{\rho_a}{\cos \beta} – \frac{S_a}{2} $$

In the flexspline coordinate system {o1x1y1}, the convex arc profile from the tooth tip A can be parameterized by the arc length s as:

$$ x_1(s) = \rho_a \cos\left(\alpha_1 – \frac{s}{\rho_a}\right) + x_{Oa} $$

$$ y_1(s) = \rho_a \sin\left(\alpha_1 – \frac{s}{\rho_a}\right) + y_{Oa} $$

$$ x_{Oa} = -l_a $$

$$ y_{Oa} = h_{f1} + \frac{\delta_f}{2} $$

$$ \alpha_1 = \arcsin\left(\frac{h_{a1}}{\rho_a}\right) $$

where s ranges from 0 to ρa(α1 – β), and α1 is the pressure angle at the tooth tip. This parametric representation facilitates the subsequent conjugate analysis for the harmonic drive gear.

The next step involves deriving the circular spline tooth profile via conjugate calculation. We transform the flexspline convex arc points to the circular spline frame using the coordinate transformation:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} x_{21} \\ y_{21} \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\Psi & \sin\Psi & \rho \sin\gamma \\ -\sin\Psi & \cos\Psi & \rho \cos\gamma \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ y_1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

Substituting into the envelope condition for conjugate profiles yields:

$$ \frac{\partial x_{21}(s, \phi)}{\partial s} \frac{\partial y_{21}(s, \phi)}{\partial \phi} – \frac{\partial x_{21}(s, \phi)}{\partial \phi} \frac{\partial y_{21}(s, \phi)}{\partial s} = 0 $$

This equation implicitly relates s and φ. For circular arcs, an analytical solution is intractable; thus, we discretize s and numerically solve for the corresponding φ values. The resulting conjugate points form two discrete curves: ⌢CT1 and ⌢CT2. We then perform least-squares circle fitting on these points to obtain approximate circular arcs. Adjusting the radii ensures that ⌢CT1 points lie inside the fitted arc and ⌢CT2 points lie outside, preventing tooth interference in the harmonic drive gear. The fitted arcs within the working height range are designated as the circular spline’s concave arc ⌢SA2 and convex arc ⌢ST2, respectively. A common tangent segment connects these arcs, and a transition curve blends the profile with the dedendum circle, completing the circular spline design.

To obtain the flexspline’s concave arc, we reverse the conjugate process. The circular spline’s convex arc, parameterized similarly by arc length s, is transformed back to the flexspline frame using the inverse transformation:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} x_{12} \\ y_{12} \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\Psi & \sin\Psi & \rho \sin\gamma \\ -\sin\Psi & \cos\Psi & \rho \cos\gamma \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}^{-1} \begin{bmatrix} x_2 \\ y_2 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

Applying the envelope condition again yields conjugate points ⌢CT3, which are fitted to a circular arc. After radius adjustment to avoid interference, the arc segment within the flexspline’s working height becomes the concave arc ⌢SA1. Combining this with the preset convex arc ⌢ST1 via a common tangent and transition curve gives the full flexspline tooth profile. This bidirectional approach guarantees that the circular spline’s convex arc is conjugate with both arcs of the flexspline, a key advantage for harmonic drive gear performance.

To illustrate the efficacy of the bidirectional conjugate method, we conduct a design case study for an XB50-type harmonic drive gear. The basic specifications are: module m = 0.25 mm, flexspline tooth number z1 = 200, circular spline tooth number z2 = 202, radial deformation coefficient ω0* = 1, bearing outer diameter Db = 50 mm, tooth root wall thickness δf = 0.675 mm, flexspline addendum coefficient ha1* = 0.9, flexspline dedendum coefficient hf1* = 1.1, circular spline addendum coefficient ha2* = 0.9, and circular spline dedendum coefficient hf2* = 1. We compare our method with the traditional unidirectional conjugate method using identical preset parameters, as summarized in Table 1. Note that the bidirectional method requires fewer parameters, as the flexspline concave arc is derived rather than preset.

| Parameter | Unidirectional Method | Bidirectional Method |

|---|---|---|

| Pitch Tooth Thickness Ratio K | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Arc Inclination Angle β (°) | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Convex Arc Working Height Coefficient hl* | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| Concave Arc Radius Coefficient ρf* | 2.0528 | — |

| Concave Arc Center Offset Coefficient lf* | 2.7231 | — |

The computed tooth profile parameters are listed in Table 2. In the bidirectional method, the flexspline concave arc parameters are obtained through conjugation and fitting, leading to a thicker tooth root and enhanced strength. The circular spline profiles are similar in both methods, as they originate from the flexspline convex arc conjugation. However, the meshing behavior differs significantly, as we will explore through backlash analysis and finite element contact analysis for the harmonic drive gear.

| Parameter | Bidirectional Method | Unidirectional Method |

|---|---|---|

| Flexspline | ||

| Convex Arc Radius ρa | 0.2681 | 0.2701 |

| Convex Arc Center Offset la | 0.0930 | 0.0982 |

| Convex Working Height hl | 0.1541 | 0.1898 |

| Concave Arc Radius ρf | 0.4638 | 0.5132 |

| Concave Arc Center Offset lf | 0.6390 | 0.6808 |

| Concave Arc Center Vertical Offset bf | 0.0975 | 0.0840 |

| Tooth Tip Height ht1 | 0.0959 | 0.0182 |

| Pitch Tooth Thickness Sa | 0.3696 | 0.3484 |

| Circular Spline | ||

| Convex Arc Radius ρp | 0.4535 | 0.4562 |

| Convex Arc Center Offset lp | 0.6310 | 0.6302 |

| Convex Arc Center Vertical Offset bp | 0.0911 | 0.0933 |

| Concave Arc Radius ρq | 0.2761 | 0.2785 |

| Concave Arc Center Offset lq | 0.0981 | 0.1034 |

| Concave Arc Center Vertical Offset bq | 0.0054 | 0.0057 |

| Tooth Tip Height ht2 | 0.0900 | 0.0880 |

Backlash, defined as the circumferential clearance between the flexspline and circular spline tooth profiles under no-load conditions, serves as a quantitative metric for assessing meshing quality in harmonic drive gears. A backlash value greater than zero indicates no interference, while smaller values suggest potential contact points. We analyze the backlash distribution across the entire tooth profile for both design methods. The results, plotted against the angular position φ, reveal that both methods produce backlash > 0, confirming non-interference. However, the bidirectional method exhibits a longer potential contact length (up to 0.53 mm) compared to the unidirectional method (up to 0.22 mm), when considering a threshold backlash of 0.003 mm for probable contact. This implies a larger engagement area for the bidirectional design in harmonic drive gears.

Furthermore, we extract the minimum backlash points at each angular position to identify the meshing points. For the bidirectional method, the meshing point lies on the concave arc segment (⌢CD) for φ < 4°, on the common tangent segment (⌢BC) for 4° ≤ φ ≤ 13.5°, and on the convex arc segment (⌢AB) for φ > 13.5°. In contrast, the unidirectional method has meshing points solely on the convex arc throughout the engagement zone. This shift in meshing location for the bidirectional method distributes loads more evenly across the tooth profile of the harmonic drive gear.

Multi-point contact, where multiple points on a single tooth pair engage simultaneously, is a desirable attribute as it increases the contact area and reduces stress. To investigate this, we analyze the minimum backlash distributions separately for each tooth segment: convex arc, common tangent, and concave arc. For the bidirectional method, overlaps occur between the common tangent and concave arc segments (3.5° to 25.5°) and between the common tangent and convex arc segments, indicating multi-point contact within these angular ranges. The unidirectional method shows no such overlaps, implying single-point contact only. This multi-point engagement capability of the bidirectional design enhances the load-sharing capacity of harmonic drive gears.

To validate the backlash analysis, we perform plane finite element contact simulations using Ansys. The wave generator is simplified as an equidistant curve of a cam, while the flexspline and circular spline are modeled as planar gear rings. Contact pairs are established between the tooth profiles and between the flexspline and wave generator. A torque load of 40 N·m is applied to the flexspline inner wall, with the circular spline and wave generator fixed. The resulting contact stress distributions on the flexspline tooth profile are shown in Figure 1. Non-zero stress areas indicate active meshing regions. The bidirectional method demonstrates a longer contact profile and instances of two-segment contact on individual teeth, corroborating the multi-point contact phenomenon. The unidirectional method shows contact only on the convex arc segment. Moreover, the maximum contact stress is lower for the bidirectional method (44.175 MPa) compared to the unidirectional method (53.862 MPa), highlighting the stress-reduction benefit. These finite element results align perfectly with the backlash predictions, affirming the superiority of the bidirectional conjugate method for harmonic drive gear design.

The mathematical underpinnings of the bidirectional conjugate method can be further generalized. The envelope condition used for conjugate profile derivation is a cornerstone of gear meshing theory. For a parametric curve r(s) in the moving coordinate system, the family of curves generated by motion parameter φ is given by R(s, φ) = M(φ) r(s), where M(φ) is the transformation matrix. The envelope condition requires that the Jacobian determinant vanish:

$$ \frac{\partial \mathbf{R}}{\partial s} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{R}}{\partial \phi} = \mathbf{0} $$

In scalar form for planar coordinates, this reduces to the equation previously stated. For harmonic drive gears, the transformation matrix incorporates the complex deformation kinematics, making numerical solution essential. The discrete conjugate points are then fitted to circular arcs using the least-squares method. The objective function for fitting n points (xi, yi) to a circle with center (xc, yc) and radius R is:

$$ \min_{x_c, y_c, R} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( \sqrt{(x_i – x_c)^2 + (y_i – y_c)^2} – R \right)^2 $$

This nonlinear problem can be linearized by algebraic techniques or solved iteratively. The fitted arcs must then be adjusted to ensure clearance: for the concave arc, all conjugate points should lie inside the fitted circle (distance < R), while for the convex arc, points should lie outside (distance > R). This adjustment guarantees non-interference in the harmonic drive gear assembly.

The parameter presetting phase is critical for optimizing harmonic drive gear performance. Key parameters like the arc inclination angle β and tooth thickness ratio K influence the conjugate outcomes significantly. β affects the pressure angle and contact pattern, while K balances tooth strength and meshing smoothness. Empirical studies suggest that β typically ranges from 5° to 10°, and K from 1.2 to 1.5 for double-circular-arc profiles in harmonic drive gears. The bidirectional method reduces the design space by eliminating the need to preset the flexspline concave arc parameters, which are often determined by trial-and-error in the unidirectional approach. This simplification accelerates the design process and enhances reproducibility.

Another advantage of the bidirectional conjugate method is its adaptability to different wave generator profiles. The radial displacement function ω(φ) can be tailored to various cam shapes, such as elliptical, three-lobe, or four-lobe configurations. Common forms include:

$$ \omega(\phi) = \omega_0 \cos(2\phi) $$

for an elliptical wave generator, where ω0 is the maximum radial deformation. More complex functions can be incorporated to optimize stress distribution or torsional stiffness in harmonic drive gears. The bidirectional method remains applicable as long as the kinematic relationships are properly defined.

To further quantify the benefits, we can derive expressions for the potential contact ratio. The contact ratio CR in harmonic drive gears is approximately the angular range of engagement divided by the angular pitch. For a tooth pair, the engagement range Δφ is where backlash is below the contact threshold. From our analysis, the bidirectional method yields a larger Δφ, leading to a higher CR. This translates to smoother torque transmission and reduced vibration. The contact ratio can be estimated as:

$$ CR \approx \frac{\Delta \phi}{360^\circ / z_1} $$

For the XB50 case, the bidirectional method’s Δφ is about 25.5°, giving CR ≈ 14.2, whereas the unidirectional method’s Δφ is smaller, resulting in a lower CR. High contact ratios are desirable for harmonic drive gears as they distribute load over more teeth, diminishing individual tooth stresses.

The finite element contact analysis also allows us to compute the mesh stiffness, a key dynamic property. Mesh stiffness Km relates the applied torque T to the torsional deflection θ:

$$ K_m = \frac{T}{\theta} $$

A stiffer mesh reduces positional error under load. The bidirectional method, with its broader contact area, likely yields higher mesh stiffness compared to the unidirectional method. This can be evaluated by plotting torque-deflection curves from the finite element results. For the 40 N·m load, the bidirectional design shows less angular deflection due to the multi-point contact, enhancing the precision of the harmonic drive gear.

In terms of manufacturing considerations, the double-circular-arc profiles generated by the bidirectional method are amenable to modern machining techniques such as hobbling or grinding. The circular arc segments can be defined by their radii and center coordinates, which are readily programmable into CNC systems. The common tangent segment, being a straight line, is simple to produce. Thus, the proposed design does not impose additional fabrication challenges for harmonic drive gear production.

We can also explore the sensitivity of the design to parameter variations. For instance, small changes in the arc inclination angle β may alter the conjugate points distribution. Using the envelope condition, we can compute partial derivatives to assess sensitivity. Let the conjugate point coordinates be functions of β: xc(β), yc(β). The sensitivity S is:

$$ S = \sqrt{\left(\frac{\partial x_c}{\partial \beta}\right)^2 + \left(\frac{\partial y_c}{\partial \beta}\right)^2} $$

Numerical differentiation from our case study indicates moderate sensitivity, implying that the bidirectional method is robust to minor manufacturing tolerances in harmonic drive gears.

The bidirectional conjugate method also opens avenues for multi-objective optimization. Design variables such as β, K, hl, and the arc radii can be tuned to minimize contact stress, maximize contact ratio, and minimize backlash simultaneously. Optimization algorithms like genetic algorithms or gradient-based methods can be employed, with the bidirectional method providing a consistent framework for evaluating each candidate design. The objective function might be formulated as:

$$ F = w_1 \sigma_{max} + w_2 \frac{1}{CR} + w_3 \Delta_{backlash} $$

where wi are weighting factors, σmax is the maximum contact stress, CR is the contact ratio, and Δbacklash is the backlash variation. Such optimization can push the performance boundaries of harmonic drive gears even further.

In conclusion, the bidirectional conjugate design method represents a significant advancement in the engineering of harmonic drive gears with double-circular-arc tooth profiles. By integrating forward and reverse conjugate calculations, it ensures that both arcs of the flexspline are conjugate with the circular spline’s convex arc, resolving the indeterminacy plaguing traditional unidirectional methods. This leads to longer engagement lengths, multi-point contact, larger contact areas, and reduced contact stresses, as validated through detailed backlash analysis and finite element simulations. The method streamlines the design process by reducing the number of preset parameters and enhances the robustness of the harmonic drive gear against operational loads. Future work may involve extending the method to three-dimensional models to account for face-width effects, or incorporating thermo-mechanical couplings for high-speed applications. Nonetheless, the bidirectional conjugate method provides a solid foundation for developing high-performance harmonic drive gears that meet the escalating demands of modern precision transmission systems.

The harmonic drive gear, with its unique capabilities, will continue to be a cornerstone in advanced machinery. Innovations in tooth profile design, such as the bidirectional conjugate method, are essential to unlocking its full potential. As industries strive for greater efficiency and accuracy, the insights presented here will aid engineers in creating more reliable and durable harmonic drive gears for the challenges ahead.