The pursuit of compact, high-ratio, and high-torque transmission solutions is a constant in mechanical engineering. Among existing technologies, strain wave gear drives, commonly known as harmonic drives, are renowned for their high reduction ratios, compact size, precision, and zero-backlash operation. However, their power transmission capacity is often limited by the stress on the flexible spline. This article introduces and analyzes a novel variant designed to overcome this limitation: the End-Face Oscillating Tooth Strain Wave Gear. This architecture synthesizes the principles of conventional strain wave gearing with those of oscillating tooth (or “live gear”) transmissions, promising to retain all the advantages of traditional harmonic drives while substantially increasing the transmissible power. We will conduct a detailed theoretical investigation into the stress state of its key meshing pair, derive formulas for meshing area and specific pressure, and provide a comparative design example to quantify its performance advantage.

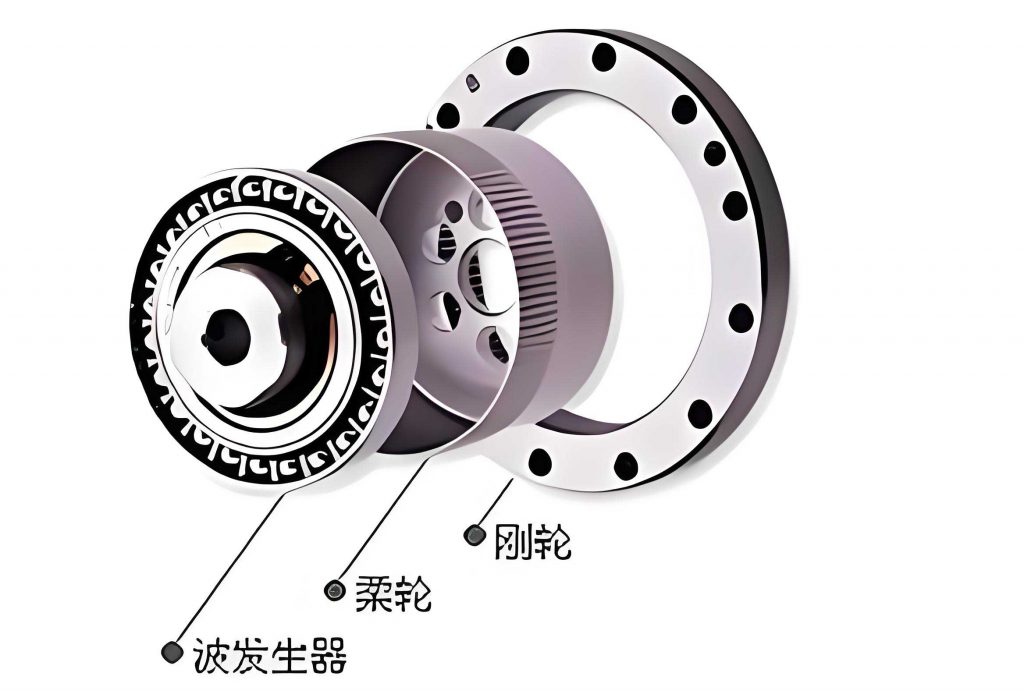

The fundamental structure of a single-sided transmission is illustrated in the figure above. The main components are the Output Shaft (1), the fixed End-Face Gear (2), the Slot Wheel (3) which is attached to the output shaft, the Oscillating Teeth (4) housed in radial slots within the slot wheel, the Wave Generator (6) with a face cam profile, and the Input Shaft (7). The working principle is as follows: as the wave generator rotates, its face cam profile engages with the rear ends of the oscillating teeth. This engagement forces the teeth to undergo axial reciprocating motion within their slots in the slot wheel. The front ends of these oscillating teeth are simultaneously in mesh with the fixed end-face gear. This dual meshing action forces the slot wheel (and thus the output shaft) to rotate relative to the end-face gear, achieving speed reduction and torque multiplication. If the slot wheel were fixed instead, the end-face gear would become the output element.

1. Force Analysis of the Meshing Pair

To understand the force transmission, it is essential to visualize the meshing pairs. A circumferential development of the gear set reveals two distinct engagement zones:

Meshing Pair A: Between the face cam of the wave generator and the rear end of the oscillating tooth (high-speed side).

Meshing Pair B: Between the front end of the oscillating tooth and the teeth of the end-face gear (low-speed, high-torque side).

For manufacturing simplicity, the tooth flanks of both pairs are typically designed as Archimedes helicoids with straight-line generators perpendicular to and intersecting the axis of rotation. While both pairs experience load, the primary focus for strength design is Meshing Pair B. This is because the total contact area in Pair A is generally larger, and the normal forces are significantly lower due to its position at the high-speed input. Consequently, the specific pressure (contact stress) in Pair B is the critical limiting factor. Our analysis will therefore concentrate exclusively on the stress state and specific pressure of Meshing Pair B.

2. Geometric Model and Total Meshing Area

A powerful tool for analyzing the concurrent engagement of multiple teeth is the “Geometric Model of Meshing State.” Conceptually, the complete tooth profile of the end-face gear is taken as a virtual datum. The engaged tip sections from the front ends of all oscillating teeth in Pair B are superimposed onto corresponding points of this virtual datum, preserving their relative engagement depth. This creates a composite model that clearly shows which teeth are in full engagement, partial engagement, or disengagement at any given instant.

Let us define key geometric parameters:

- $z_E$: Number of teeth on the end-face gear.

- $z_O$: Theoretical total number of oscillating teeth.

- $U$: Number of waves on the wave generator (typically $U \ge 2$).

- $m$: Module at the outer radius of the end-face gear.

- $h$: Tooth height of the end-face gear (and oscillating tooth front end).

- $\phi_d$: Tooth width coefficient of the end-face gear.

- $R_1, R_2$: Inner and outer radius of the end-face gear working flank, where

$$R_1 = \frac{m z_E (1 – 2\phi_d)}{2}, \quad R_2 = \frac{m z_E}{2}.$$

2.1 Maximum Meshing Area of a Single Pair ($S_e$)

The maximum possible contact area for a single Meshing Pair B occurs when an oscillating tooth is in full engagement with the end-face gear. This area $S_e$ is equivalent to the area of the working tooth flank on the oscillating tooth’s front end (or the corresponding portion of the end-face gear). The tooth surface (rising engagement section) can be described parametrically as:

$$

\begin{cases}

x = r \cos \phi_O \\

y = r \sin \phi_O \\

z = -A \phi_O

\end{cases}

\qquad (R_1 < r < R_2, \; 0 < \phi_O < \pi / z_O)

$$

where $A = h z_E / \pi$, and $\phi_O$ is a parameter related to the oscillating tooth’s angular position. Applying the surface area formula and integrating yields the closed-form expression for the maximum single-pair meshing area:

$$

S_e = \frac{\pi}{z_O} \left[ \frac{R_2 \sqrt{R_2^2 + A^2}}{2} – \frac{R_1 \sqrt{R_1^2 + A^2}}{2} + \frac{A^2}{2} \ln \left( \frac{R_2 + \sqrt{R_2^2 + A^2}}{R_1 + \sqrt{R_1^2 + A^2}} \right) \right].

$$

2.2 Variation of Total Meshing Area ($\sum S_{ej}$)

Not all oscillating teeth are in the working (load-bearing) engagement zone simultaneously. As the wave generator rotates, teeth cyclically enter, traverse, and exit the working zone. Therefore, the total contact area $\sum S_{ej}$ of all active Meshing Pairs B varies periodically with the wave generator’s rotation angle $\phi_W$. The change follows a sawtooth-like pattern with a period $T$. If the end-face gear is fixed, $T = 2\pi / z_O$; if the slot wheel is fixed, $T = 2\pi / z_E$. The total area oscillates between a maximum ($\sum S_{e_{\text{max}}}$) and a minimum ($\sum S_{e_{\text{min}}}$) value. These extrema depend critically on whether the ratio $z_O / U$ is an even or odd integer.

2.3 Total Meshing Area for $z_O / U$ as an Even Integer

When $z_O / U$ is even, within one wave, when one oscillating tooth is in full engagement, another is completely disengaged. The number of teeth in working engagement per wave is $z_N = z_O / (2U)$. The engagement zone model is divided into $z_N$ equal segments. The individual areas of the active pairs form an arithmetic progression: $\frac{S_e}{z_N}, \frac{2S_e}{z_N}, \dots, \frac{z_N S_e}{z_N}$. Summing these across all $U$ waves gives the global extrema:

$$

\sum S_{e_{\text{max}}} = U \cdot \frac{1+2+\cdots+z_N}{z_N} S_e = \frac{z_O + 2U}{4} S_e,

$$

$$

\sum S_{e_{\text{min}}} = \sum S_{e_{\text{max}}} – U S_e = \frac{z_O – 2U}{4} S_e.

$$

2.4 Total Meshing Area for $z_O / U$ as an Odd Integer

When $z_O / U$ is odd, within one wave, full engagement of one tooth does not coincide with the complete disengagement of another. The number of working teeth per wave is $z_N = (z_O + U) / (2U)$. The model is divided into $(2z_N – 1)$ segments, leading to a different arithmetic progression for the individual areas: $\frac{S_e}{2z_N-1}, \frac{3S_e}{2z_N-1}, \dots, \frac{(2z_N-1)S_e}{2z_N-1}$. The global total areas are:

$$

\sum S_{e_{\text{max}}} = U \cdot \frac{1+3+\cdots+(2z_N -1)}{2z_N – 1} S_e = \frac{(z_O + U)^2}{4 z_O} S_e,

$$

$$

\sum S_{e_{\text{min}}} = \sum S_{e_{\text{max}}} – U S_e = \frac{(z_O – U)^2}{4 z_O} S_e.

$$

The following table summarizes the formulas for the total meshing area.

| Condition for $z_O/U$ | Maximum Total Area $\sum S_{e_{\text{max}}}$ | Minimum Total Area $\sum S_{e_{\text{min}}}$ |

|---|---|---|

| Even Integer | $\dfrac{z_O + 2U}{4} S_e$ | $\dfrac{z_O – 2U}{4} S_e$ |

| Odd Integer | $\dfrac{(z_O + U)^2}{4 z_O} S_e$ | $\dfrac{(z_O – U)^2}{4 z_O} S_e$ |

3. Normal Force on Meshing Pair B

To determine the contact stress, we must find the total normal force $\sum F_{ENj}$ transmitted through all active Meshing Pairs B. We analyze the forces on a single oscillating tooth (e.g., the $j$-th tooth), assuming friction and tooth weight are negligible and load is uniformly distributed along the tooth width (radial direction).

For the $j$-th tooth in working engagement, let:

- $q_{WPj} dr$: Circumferential force component on a rear-end微元 $dr$ from the wave generator (Pair A).

- $q_{ENj} dr$: Normal force component on a front-end微元 $dr$ from the end-face gear (Pair B).

The input torque $T_i$ is the sum of contributions from all $z_N$ active teeth via Pair A:

$$

T_i = \int_{R_1}^{R_2} \sum_{j=1}^{z_N} q_{WPj} \, r \, dr.

$$

The relationship between the force components on both ends of the tooth, derived from force equilibrium and geometry (considering the spiral lead angle $\theta$ of the face cam and the tooth semi-angle $\alpha$ of the end-face gear), is:

$$

\sum q_{WPj} dr = \sum q_{ENj} \tan \theta \sin \alpha \, dr.

$$

The angles $\theta$ and $\alpha$ vary with radius $r$:

$$

\tan \theta = \frac{h U}{\pi r}, \quad \tan \alpha = \frac{\pi r}{h z_E}, \quad \sin \alpha = \frac{\pi r}{\sqrt{\pi^2 r^2 + z_E^2 h^2}}.

$$

Substituting these relations into the torque equation allows us to solve for the sum of the distributed normal force densities:

$$

\sum_{j=1}^{z_N} q_{ENj} = \frac{T_i}{\int_{R_1}^{R_2} \frac{h U r}{\pi \sqrt{\pi^2 r^2 + z_E^2 h^2}} \, dr} = \frac{2\pi^2 T_i}{h U \left( \sqrt{\pi^2 R_2^2 + z_E^2 h^2} – \sqrt{\pi^2 R_1^2 + z_E^2 h^2} \right)}.

$$

The total normal force $\sum F_{ENj}$ is found by integrating this density over the tooth width $B_E = \phi_d m z_E$:

$$

\sum_{j=1}^{z_N} F_{ENj} = \left( \sum_{j=1}^{z_N} q_{ENj} \right) B_E.

$$

Substituting $T_i = 9.55 \times 10^6 \, P_i / n_i$ (where $P_i$ is input power in kW and $n_i$ is input speed in rpm) and the expressions for $R_1$, $R_2$, and $B_E$, we obtain the final formula for the total normal force on Meshing Pair B:

$$

\boxed{\sum F_{ENj} = \frac{1.91 \times 10^7 \, \phi_d m \pi^2 \, P_i}{n_i h U \left( \sqrt{\pi^2 m^2 + 4h^2} – \sqrt{\pi^2 m^2 (1-2\phi_d)^2 + 4h^2} \right)}}.

$$

4. Specific Pressure (Contact Stress) Calculation

The specific pressure $\sigma$ (average contact stress) on Meshing Pair B is defined as the total normal force divided by the total contact area. The most critical condition occurs when the total area is at its minimum, leading to the maximum specific pressure $\sigma_{\text{max}}$. Assuming uniform pressure distribution among all active pairs:

$$

\sigma_{\text{max}} = \frac{\sum F_{ENj}}{\sum S_{e_{\text{min}}}}.

$$

Substituting the expressions for $\sum F_{ENj}$ and the appropriate $\sum S_{e_{\text{min}}}$ yields the design formulas for maximum specific pressure.

For $z_O / U$ as an even integer:

$$

\boxed{\sigma_{\text{max}} = \frac{7.64 \times 10^7 \, \phi_d m \pi^2 \, P_i}{n_i h U \left( \sqrt{\pi^2 m^2 + 4h^2} – \sqrt{\pi^2 m^2 (1-2\phi_d)^2 + 4h^2} \right) (z_O – 2U) S_e}}.

$$

For $z_O / U$ as an odd integer:

$$

\boxed{\sigma_{\text{max}} = \frac{7.64 \times 10^7 \, \phi_d m \pi^2 \, z_O \, P_i}{n_i h U \left( \sqrt{\pi^2 m^2 + 4h^2} – \sqrt{\pi^2 m^2 (1-2\phi_d)^2 + 4h^2} \right) (z_O – U)^2 S_e}}.

$$

These formulas provide the essential tool for the strength-based design of the end-face oscillating tooth strain wave gear, ensuring the contact stress remains below the allowable limit for the chosen materials.

5. Design Example and Comparative Analysis

To illustrate the potential of this novel strain wave gear design, we compare its power capacity with that of a standard spur gear reducer under identical constraints.

Common Parameters for Both Transmissions:

- Module, $m = 6 \text{ mm}$

- Material: 45 Steel, heat-treated (quenched and tempered)

- Input Speed, $n_i = 1470 \text{ rpm}$

- Total Reduction Ratio, $i = 24$

Parameters for the End-Face Oscillating Tooth Strain Wave Gear:

- $z_E = 50$, $z_O = 48$, $U = 2$ (Note: $z_O/U = 24$, an even integer)

- Tooth width coefficient, $\phi_d = 0.15$

- Tooth semi-angle at outer radius, $\alpha_2 = 30^\circ$

- Tooth height, $h = (\pi m) / (2 \tan \alpha_2) \approx 16.33 \text{ mm}$

Using Eq. (3), we calculate $S_e \approx 853.4 \text{ mm}^2$. For preliminary sizing, we assume an allowable specific pressure $\sigma_{\text{max}} = 10 \text{ MPa}$, based on guidelines for spline connections under dynamic loading. Applying the even-integer formula for $\sigma_{\text{max}}$ and solving for $P_i$ yields the maximum transmissible input power.

Parameters for the Two-Stage Spur Gear Reducer:

- Second stage pinion teeth, $z_{2,1} = 24$; gear teeth, $z_{2,2} = 100$ (ratio $u \approx 4.17$).

- Gear width $b = 122 \text{ mm}$, pinion diameter $d_1 = 144 \text{ mm}$.

- Using standard AGMA/ISO contact stress formulas with appropriate factors (load factor $K=1.2$, zone factor $Z_H=2.5$, elasticity factor $Z_E=189.8 \sqrt{\text{MPa}}$, contact ratio factor $Z_{\epsilon}=0.88$) and an allowable contact stress $[\sigma_H] = 362 \text{ MPa}$ for the heat-treated 45 steel, we calculate the permissible input torque for the second stage, then back-calculate to the first stage input power.

The results of this comparison are summarized in the table below.

| Transmission Type | Module (mm) | Material | Input Speed (rpm) | Ratio | Max. Input Power (kW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End-Face Oscillating Tooth Strain Wave Gear | 6 | 45 Steel (QT) | 1470 | 24 | 66 |

| Two-Stage Spur Gear Reducer | 6 | 45 Steel (QT) | 1470 | 24 | 4 |

The result is striking: under the same basic geometric and material constraints, the novel strain wave gear design demonstrates a potential power capacity over 16 times greater than a conventional spur gear train of the same ratio and module. This vividly highlights the primary advantage of this architecture: its ability to distribute the transmitted load over a large number of simultaneously engaging teeth (multi-tooth contact), drastically reducing specific pressure and enabling much higher power density.

6. Conclusion

This theoretical investigation has established a foundational framework for analyzing the critical load-bearing component of the end-face oscillating tooth strain wave gear. By developing a geometric model of the meshing state, we derived analytical expressions for the variable total contact area of Meshing Pair B, identifying its periodic maximum and minimum values based on the parity of $z_O/U$. Through static force analysis, we obtained the formula for the total normal force acting on this pair. Combining these results yielded the key design equations for calculating the maximum specific pressure, which is the primary criterion for contact strength design.

The comparative design example, though simplified, provides compelling quantitative evidence of the significant advantage in power density that this novel strain wave gear configuration can offer over traditional gear forms. This work thus provides a reliable theoretical basis for the strength design and optimization of this promising transmission technology, paving the way for its application in heavy-duty fields such as mining, metallurgy, and construction machinery where high-ratio, high-torque, and compact drives are essential. Future work should focus on experimental validation of these theoretical models, investigation of fatigue life under cyclic loading, and comprehensive efficiency analysis including friction losses in the oscillating tooth slots.