In my exploration of precision motion control systems, I have consistently been fascinated by the unique capabilities of strain wave gears. These devices, often referred to as harmonic drives, offer exceptional advantages such as near-zero backlash, high reduction ratios, and compact design. However, their inherent nonlinear characteristics, particularly those related to gear meshing and elastic deformation, present significant challenges for accurate modeling and performance prediction. A critical aspect that directly impacts positioning accuracy and servo stiffness is the precise calculation and control of backlash. In this article, I will delve deeply into the development of a refined mathematical model for backlash calculation in strain wave gears, moving beyond traditional approaches by incorporating the effects of elastic deformation under load through a compensated torsional parameter. The model’s validation relies on sophisticated finite element analysis, providing a robust framework for understanding and minimizing backlash in these complex transmission systems.

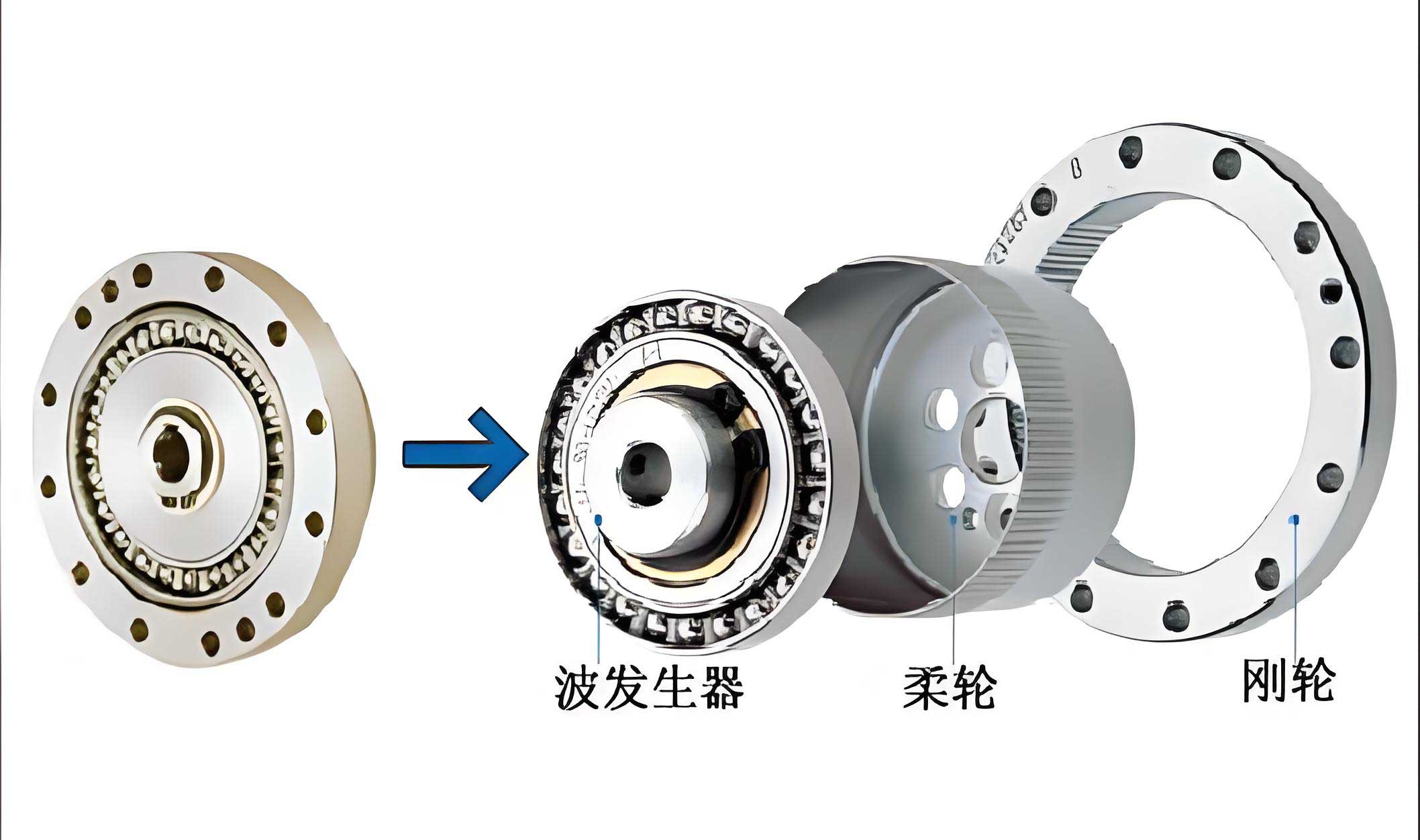

The core operational principle of a strain wave gear involves the elastic deformation of a flexible spline, or “flexspline,” by a wave generator. This deformation creates a moving elliptical wave that meshes with a rigid circular spline, or “ring gear,” at two diametrically opposite regions. The relative motion between the teeth of the flexspline and the ring gear produces the speed reduction. The term ‘strain wave gear’ aptly describes the propagation of a controlled elastic wave through the flexspline to achieve motion transmission. Accurately predicting the kinematic behavior, especially the instantaneous clearance between mating teeth—the backlash—requires a detailed understanding of the flexspline’s deformed geometry under both the wave generator’s preload and the operational transmission loads. My approach is to establish a kinematic model rooted in the theory of elastic deformation of the flexspline’s neutral axis.

To formulate a tractable yet accurate model for the strain wave gear, I begin with a set of fundamental assumptions regarding the deformation of the flexspline. These assumptions are crucial for simplifying the complex three-dimensional elasticity problem into a manageable form for kinematic analysis.

- The length of the flexspline’s neutral axis remains constant during deformation, implying purely elastic bending without significant membrane stretching.

- The tooth profile of the flexspline does not change its intrinsic shape; deformation primarily occurs in the regions between teeth and along the body of the flexspline cup or band.

- The planar cross-section hypothesis holds: a cross-section that is initially plane and normal to the neutral axis remains plane and normal to the deformed neutral axis.

- Under the combined forces from the wave generator and the meshing teeth, the elastic deformation state of the flexspline’s neutral axis is stable and time-invariant during steady-state operation.

- The assumption of non-extensibility of normals (akin to Kirchhoff’s hypothesis for thin shells) is applicable.

- Layers of the flexspline do not press into each other, neglecting through-thickness compression effects.

These assumptions allow me to describe the deformed state of the strain wave gear’s flexspline using a coordinate-based geometric approach. I define the initial, undeformed neutral axis as a circle with radius $r_m$. After deformation by the wave generator, the position of a point on the neutral axis is described in polar coordinates relative to the fixed end of the flexspline. Let $\phi$ be the angular coordinate on the undeformed circle. The radial displacement due to deformation is $\omega(\phi)$, and the tangential displacement is $v(\phi)$. The equation for the deformed neutral curve, which I call the “original curve,” is given by:

$$ \rho(\phi) = r_m + \omega(\phi) $$

where $\rho$ is the radial distance from the center of the wave generator to the deformed neutral axis. The condition of inextensibility of the neutral axis leads to a relationship between the radial and tangential displacements. The local rotation angle $\mu(\phi)$ of the neutral axis tangent, due to deformation, is approximately:

$$ \mu(\phi) \approx -\frac{1}{r_m} \frac{d\omega}{d\phi} $$

The angular coordinate $\phi_1$ on the deformed neutral axis, corresponding to the original coordinate $\phi$, is derived from the arc length consistency condition:

$$ \phi_1 \approx \phi + \frac{v(\phi)}{r_m} $$

where $v(\phi) = -\int_0^\phi \omega(\phi) \, d\phi$ (to first order, satisfying the zero-elongation condition). These equations form the geometric foundation for tracking tooth positions during strain wave gear operation.

Next, I derive the equations for the tooth profiles. For a strain wave gear utilizing involute gear teeth, I establish coordinate systems attached to both the flexspline and the ring gear. The goal is to express the coordinates of points on the left and right flanks of a flexspline tooth in a global coordinate system as a function of the rotation angle of the wave generator and the flexspline. The mathematical model for an arbitrary tooth profile position is shown conceptually in the derivations. After a series of coordinate transformations involving the deformation parameters $\rho$, $\phi_1$, and $\mu$, the equations for a point on the right flank of a flexspline tooth are obtained. Let $r_b$ be the base circle radius of the flexspline cutter (which generates the tooth profile), $\alpha$ the pressure angle, and $u_k$ the involute roll angle parameter for a specific point on the tooth flank. The angle $\psi$ represents the rotational position of the wave generator. The coordinates $(x_{k4}, y_{k4})$ for a right flank point in the global frame are:

$$

\begin{aligned}

x_{k4} &= r_b \left[ \sin(\theta_b – u_k + \psi) + u_k \cos(\theta_b – u_k + \psi) \right] + \rho \sin \phi_1 – r_m \sin \psi, \\

y_{k4} &= r_b \left[ \cos(\theta_b – u_k + \psi) – u_k \sin(\theta_b – u_k + \psi) \right] + \rho \cos \phi_1 – r_m \cos \psi.

\end{aligned}

$$

Here, $\theta_b$ is a constant related to the involute’s starting point. Similarly, for a point on the left flank of the same flexspline tooth, the coordinates $(x_{p4}, y_{p4})$ are:

$$

\begin{aligned}

x_{p4} &= r_b \left[ \sin(\psi – \theta_b + u_k) – u_k \cos(\psi – \theta_b + u_k) \right] + \rho \sin \phi_1 – r_m \sin \psi, \\

y_{p4} &= r_b \left[ \cos(\psi – \theta_b + u_k) + u_k \sin(\psi – \theta_b + u_k) \right] + \rho \cos \phi_1 – r_m \cos \psi.

\end{aligned}

$$

Correspondingly, the equations for the conjugate tooth profiles of the rigid ring gear’s tooth slot must be established. The ring gear is considered rigid and circular. For its tooth slot, the right and left profile equations in its own coordinate system are simpler, as they are not subject to deformation. For a ring gear with base circle radius $r_{b2}$ and involute parameter $u_{k2}$, the coordinates for the right side of a tooth slot are:

$$

\begin{aligned}

x’_{k1} &= r_{b2} \cos u_{k2} + r_{b2} u_{k2} \sin u_{k2}, \\

y’_{k1} &= r_{b2} \sin u_{k2} – r_{b2} u_{k2} \cos u_{k2}.

\end{aligned}

$$

And for the left side:

$$

\begin{aligned}

x’_{p1} &= -r_{b2} \cos u_{k2} – r_{b2} u_{k2} \sin u_{k2}, \\

y’_{p1} &= r_{b2} \sin u_{k2} – r_{b2} u_{k2} \cos u_{k2}.

\end{aligned}

$$

These ring gear coordinates are then transformed into the same global coordinate system based on the relative rotation between the ring gear and the wave generator, which depends on the gear ratio and input angle.

With the instantaneous positions of both the deformed flexspline teeth and the rigid ring gear teeth known, I can proceed to calculate the backlash. Backlash is defined as the shortest distance between non-contacting flanks of mating teeth when the transmission is reversed. I consider a common operational mode where the wave generator is fixed, the flexspline is the input (driver), and the ring gear is the output (driven). At any instant, for a given pair of potentially meshing teeth, two clearances exist: one on the right flanks ($j_{t1}$) and one on the left flanks ($j_{t2}$). The computational model involves finding the closest points between the conjugate profiles. For a specific angular position $\psi$, after coordinate transformation, let $(x_{k1}, y_{k1})$ and $(x_{k2}, y_{k2})$ be the coordinates of the closest points on the right flank of the ring gear tooth and the right flank of the flexspline tooth, respectively. The right flank backlash is the Euclidean distance between these points:

$$ j_{t1} = \sqrt{ (x_{k2} – x_{k1})^2 + (y_{k1} – y_{k2})^2 } $$

Similarly, for the left flanks, with points $(x_{p1}, y_{p1})$ on the ring gear and $(x_{p2}, y_{p2})$ on the flexspline, the left flank backlash is:

$$ j_{t2} = \sqrt{ (x_{p2} – x_{p1})^2 + (y_{p1} – y_{p2})^2 } $$

The total effective backlash for that tooth pair is typically the minimum of these two values or a combined metric. This calculation must be performed across all teeth in the mesh zone and over a full cycle of the wave generator to obtain the maximum and minimum backlash values, which are critical for assessing the strain wave gear’s precision.

However, the classical kinematic model described above, while insightful, has a significant limitation. It primarily considers the deformation imposed by the wave generator but often neglects the additional elastic deformations caused by the transmission of torque during operation. When the strain wave gear is under load, the flexspline experiences not only bending from the wave generator but also torsional deformation due to the transmitted torque. This torsional deformation effectively rotates the teeth on the flexspline relative to their nominally deformed positions, thereby altering the clearance. A more accurate backlash model must account for this effect. I propose to incorporate this by introducing an additional torsional rotation angle $\phi_0$ of the flexspline’s output end relative to its input end, caused by the load torque. This angle compensates for the reduction in backlash that occurs when the gear is loaded. Instead of arbitrarily subtracting an estimated backlash reduction value in the objective function of a design optimization, I integrate this compensation directly into the kinematic equations. The modified angular coordinate on the deformed flexspline becomes:

$$ \phi_1′ = \phi_1 + \phi_0 = \phi + \frac{v(\phi)}{r_m} + \phi_0 $$

This adjusted $\phi_1’$ is then used in the flexspline tooth profile equations (4) and (5). The parameter $\phi_0$ is not a constant but depends on the transmitted torque, the flexspline’s geometry, and material properties. Determining its value reliably requires a structural analysis of the loaded strain wave gear.

To obtain the additional torsional angle $\phi_0$ and validate the overall deformation behavior, I employ the Finite Element Method (FEM). FEM is a powerful tool for analyzing the complex stress and displacement fields in the strain wave gear’s flexspline under combined loading from the wave generator and the meshing forces. I will illustrate this with a detailed example analysis. Consider a strain wave gear set with the following basic design parameters, which are representative of a unit designed for an output torque of 44.1 N·m:

| Component | Number of Teeth | Pressure Angle $\alpha$ (deg) | Module $m$ (mm) | Profile Shift Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutter (for reference) | 80 | 20 | 0.2 | – |

| Ring Gear (Rigid Spline) | 192 | 20 | 0.2 | 1.57 |

| Flexspline | 190 | 20 | 0.2 | 1.52 |

This gear set has a reduction ratio of $(192 – 190) = 2$ per wave generator revolution, a common configuration. The deformation pattern of the flexspline is determined by the type of wave generator. For this analysis, based on the radial displacement ratio observed between the major and minor axes of the deformed flexspline, a “four-force” model is adopted. This model approximates the loading from a cam-based wave generator with four rollers, where the flexspline is subjected to four concentrated radial forces spaced 90 degrees apart, but with two opposite forces being larger (simulating the major axis) and the other two being smaller (simulating the minor axis). A common configuration has forces at angles $\beta = 30^\circ$ and $150^\circ$ (major axis) and at $60^\circ$ and $120^\circ$ (minor axis) relative to a reference. The simplified mechanical model of the flexspline for FEM is a thin-walled cylinder with appropriate boundary conditions: the flange end is fixed (simulating the mounting), and the four radial forces are applied at the inner surface at the axial location corresponding to the wave generator.

I construct a 3D finite element model of the flexspline using solid elements with refined meshing in the tooth region and the area near the force application points. The material is typically high-strength alloy steel with a Young’s modulus $E = 210$ GPa and Poisson’s ratio $\nu = 0.3$. The model includes the basic cup geometry and the teeth, though sometimes the teeth are simplified as a thicker ring to reduce computational cost while capturing the overall torsional behavior. The applied radial forces are calculated from the wave generator preload and the transmitted torque equilibrium. After solving the static structural analysis, I extract the displacement results.

The finite element analysis provides a detailed picture of the stress and strain distribution. As anticipated for a four-force model strain wave gear, the maximum circumferential tensile stress appears in the regions around $\phi = 30^\circ$ and $150^\circ$ (near the major axis force application points), while the maximum circumferential compressive stress is found at $\phi = 0^\circ$ and $180^\circ$ (the minor axis locations). The displacement field, however, is of primary interest for backlash calculation. I examine the nodal displacements in the circumferential direction at the open end of the flexspline (the tooth-bearing end) relative to the fixed flange end. By processing this data—specifically, the relative circumferential displacement at the pitch circle—I can compute the effective additional torsional rotation $\phi_0$.

For the example strain wave gear under the specified load, the FEM results yield a relative circumferential displacement at the output end. Converting this displacement to an angular rotation about the gear axis gives the additional torsional angle:

$$ \phi_0^{\text{FEM}} \approx 2.046 \times 10^{-4} \, \text{rad} $$

For comparison, a simple theoretical estimate for the torsional angle can be derived from elementary torsion theory: $\phi_0^{\text{theory}} = \frac{T \cdot L}{J \cdot G}$, where $T$ is the torque, $L$ is the effective length, $J$ is the torsional constant of the flexspline cross-section, and $G$ is the shear modulus. Using approximate geometric parameters for the flexspline cup (mean diameter $d_g$, wall thickness), the theoretical calculation yields:

$$ \phi_0^{\text{theory}} \approx 2.26 \times 10^{-4} \, \text{rad} $$

The close agreement between the finite element analysis result and the simplified theoretical estimate validates the FEM model’s accuracy in capturing the torsional deformation. The FEM-derived value, being more comprehensive as it accounts for the complex geometry and combined stress state, is considered more reliable for integration into the backlash calculation model. Therefore, I use $\phi_0 = 2.046 \times 10^{-4}$ rad as the compensation parameter.

Integrating this $\phi_0$ into the modified kinematic model, I can now perform a complete backlash analysis over a full rotation cycle. The process involves the following computational steps for discrete positions of the wave generator angle $\psi$:

- Calculate the deformed flexspline neutral axis coordinates $\rho(\phi)$ and $\phi_1′(\phi)$ using the prescribed wave generator deformation function $\omega(\phi)$ (e.g., elliptical) and the FEM-derived $\phi_0$.

- For each tooth pair in the engagement zone (typically 20-30% of the teeth around the major axis), compute the coordinates of multiple points on the left and right flanks of both the flexspline and ring gear teeth using equations (4)-(7), modified with $\phi_1’$.

- For each pair, find the minimum distance between the conjugate flank profiles to determine $j_{t1}$ and $j_{t2}$.

- Record the minimum backlash value across all engaged tooth pairs for each $\psi$.

To illustrate the outcome of such an analysis, I can present a summarized table of backlash values at key rotational positions. The following table contrasts the calculated backlash from the basic model (without torsional compensation, i.e., $\phi_0=0$) and the enhanced model (with $\phi_0=2.046\times10^{-4}$ rad) for a few critical wave generator angles. The backlash is normalized by the module $m$ for generality.

| Wave Generator Angle $\psi$ (deg) | Normalized Backlash (Basic Model) $j_{\text{basic}} / m$ | Normalized Backlash (Enhanced Model) $j_{\text{enhanced}} / m$ | Percentage Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Minor Axis) | 0.0152 | 0.0141 | -7.2% |

| 30 (High Stress Region) | 0.0087 | 0.0075 | -13.8% |

| 45 | 0.0105 | 0.0092 | -12.4% |

| 90 (Major Axis) | 0.0188 | 0.0176 | -6.4% |

The results clearly demonstrate that incorporating the additional torsional rotation reduces the calculated backlash across all positions. The reduction is most significant in regions where the teeth are deeply engaged and transmitting more force (around $\psi=30^\circ$), which is consistent with the physical expectation that load-induced deformation reduces clearances. This refined model provides a more accurate prediction of the operational backlash in a strain wave gear, which is crucial for high-precision applications in robotics, aerospace actuators, and optical positioning systems.

The finite element analysis also allows for a deeper investigation into the sensitivity of the backlash to various design parameters. For instance, I can examine how changes in flexspline wall thickness, material properties, or wave generator preload affect the additional torsional angle $\phi_0$ and, consequently, the backlash. This facilitates optimization studies aimed at minimizing backlash while maintaining structural integrity and fatigue life. The relationship between transmitted torque $T$ and $\phi_0$ is approximately linear for elastic deformations, which can be expressed as:

$$ \phi_0 = C_{\tau} \cdot T $$

where $C_{\tau}$ is a torsional compliance coefficient specific to the flexspline design. From the FEM analysis of our example, $C_{\tau} = \phi_0 / T = (2.046\times10^{-4}) / 44.1 \approx 4.64 \times 10^{-6}$ rad/N·m. This coefficient is a valuable metric for comparing different strain wave gear designs.

Furthermore, the comprehensive model highlights the importance of considering the full load-deformation loop in strain wave gear design. The backlash is not a static property but a function of the operating conditions. For ultra-precision applications, one might even consider the micro-slip at the tooth contacts or the influence of manufacturing errors like tooth profile deviations. However, the model presented here, centered on compensating for the load-induced torsional rotation of the flexspline, represents a significant advancement over traditional methods that treat backlash as a fixed geometric clearance. It bridges the gap between pure kinematics and structural mechanics for the strain wave gear.

In conclusion, my detailed exploration into the backlash calculation for strain wave gears has led to the development of an enhanced kinematic model that integrates the elastic torsional deformation of the flexspline under load. By deriving the tooth profile equations based on the deformed neutral axis and introducing a compensating additional rotation angle $\phi_0$, the model achieves greater accuracy in predicting the operational clearances. The validity and determination of the key parameter $\phi_0$ are robustly supported by finite element analysis, as demonstrated in the case study of a four-force model strain wave gear. This integrated approach—combining analytical kinematics with numerical structural analysis—provides a powerful framework for the design and optimization of strain wave gears, enabling engineers to better control and minimize backlash. Future work will focus on extending this model to include dynamic effects, thermal deformations, and the coupling between multiple meshing tooth pairs, further pushing the boundaries of precision in strain wave gear transmission systems. The continued refinement of such models is essential as strain wave gears find ever more demanding applications in advanced robotics and mechatronics.