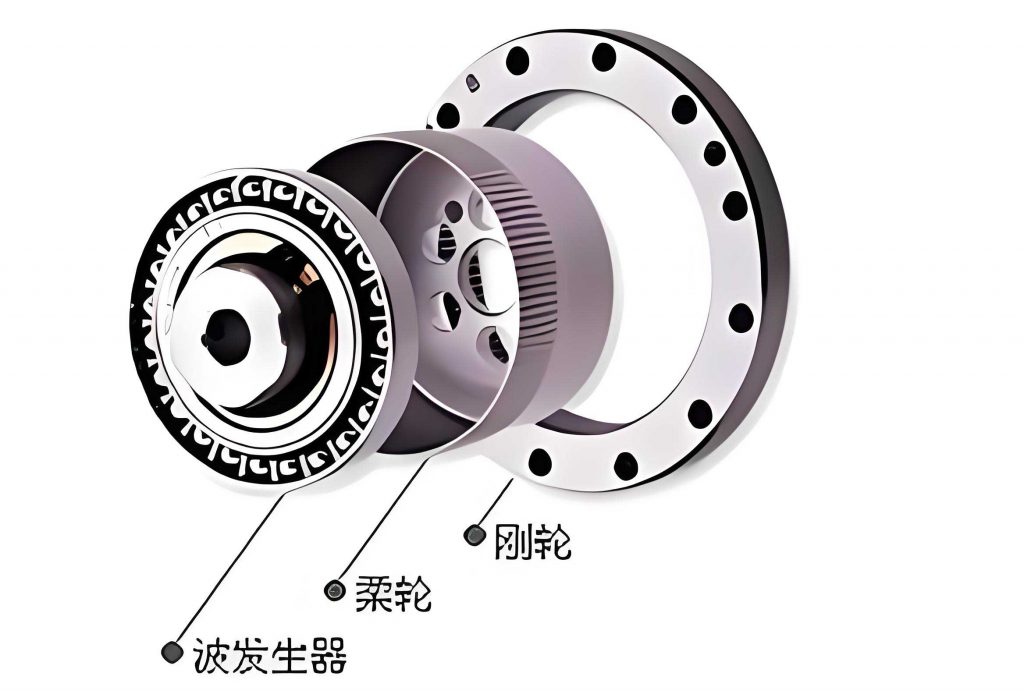

The strain wave gear, also known as harmonic drive, represents a pivotal advancement in precision motion control technology. Its unique operating principle, relying on the controlled elastic deformation of a thin-walled component, grants it unparalleled advantages in applications demanding compactness, high reduction ratios, and exceptional positional accuracy. These advantages have cemented its role in critical fields such as aerospace robotics, satellite mechanisms, and advanced industrial automation. At the heart of this system lies the flexspline, a compliant cup-shaped or ring-shaped gear with external teeth. This component undergoes repeated elastic deformation during each rotation of the wave generator, making its structural integrity paramount. Fatigue failure, often manifesting as cracks in high-stress regions, remains a primary concern for the long-term reliability of strain wave gear. Consequently, a profound understanding of the deformation behavior and stress distribution within the flexspline, under both assembly and operational loads, is a fundamental research objective for optimizing design and enhancing service life.

However, achieving precise theoretical solutions for the flexspline’s mechanical state is notoriously complex. The challenges stem from the intricate geometry (including teeth and transitional fillets), the non-linear contact conditions with the wave generator, and the dynamic nature of meshing forces. To overcome these hurdles, the Finite Element Method (FEM) has become an indispensable tool. Traditional modeling approaches often simplify the analysis by employing shell elements for the flexspline and applying equivalent forced displacements or distributed loads to simulate the wave generator’s influence. While computationally efficient, these methods may overlook critical three-dimensional stress states and transient dynamic effects. Some studies employ static contact analysis but seldom capture the full dynamic response under operational loads. This study aims to bridge this gap by developing a high-fidelity three-dimensional solid model of a strain wave gear assembly within the ABAQUS/CAE environment. The core methodology involves simulating two critical phases: the press-fit assembly of the wave generator into the flexspline and the subsequent dynamic operation under load. By treating the wave generator as a rigid analytical surface and employing explicit dynamics for the operational phase, this investigation seeks to provide a comprehensive and accurate depiction of the flexspline’s deformation and stress evolution.

1. Three-Dimensional Finite Element Model Development

The object of this study is a standard cup-type strain wave gear with a double-wave configuration. The key operational parameters are defined as follows: an output torque of $T = 30 \text{ N·m}$, a wave generator input speed of $\omega_B = 3000 \text{ rpm}$, and a gear ratio of $u = 100$. The primary geometric parameters for the gear pair are summarized in Table 1.

| Component | Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexspline | Module | $m$ | 0.3 mm |

| Number of Teeth | $z_R$ | 200 | |

| Pressure Angle | $\alpha$ | 20° | |

| Profile Shift Coefficient | $x_R$ | +3.45 | |

| Reference Diameter | $d_R$ | 60.0 mm | |

| Circular Spline | Number of Teeth | $z_G$ | 202 |

| Pressure Angle | $\alpha$ | 20° | |

| Profile Shift Coefficient | $x_G$ | +3.48 | |

| Inside Diameter | $d_{aG}$ | 62.088 mm |

1.1 Geometric Modeling and Simplifications

To balance model fidelity with computational cost, strategic simplifications were applied. The flexspline was modeled with its essential features: the main cup body, the toothed rim, and the mounting flange. Small stress-relief fillets at the junction between the tooth rim and the cylindrical shell were omitted, while the larger, more critical fillets at the cup bottom and the flange junction were retained to prevent unrealistic stress concentrations. The key dimensions of the simplified flexspline are: cup length $L = 48 \text{ mm}$, nominal shell thickness $\delta = 0.48 \text{ mm}$, rim width $b_R = 12 \text{ mm}$, and bottom fillet radius $R_2 = 3 \text{ mm}$.

The wave generator, typically comprising an elliptical cam and a specially designed “wave” ball bearing, was significantly simplified. The complex bearing assembly was not modeled in detail. Instead, the wave generator was represented as a rigid analytical surface whose profile corresponds to the outer race of the flexible bearing. This profile is defined by a cosine function, a common approximation for the deformation curve of the strain wave gear flexspline. In a polar coordinate system centered on the wave generator, the radial coordinate $\rho_R$ is given by:

$$\rho_R = R_m + \omega_0 \cos(2\phi)$$

where $R_m = 30 \text{ mm}$ is the nominal radius of the undeformed flexspline inner wall, $\omega_0 = 0.285 \text{ mm}$ is the nominal radial deformation amplitude, and $\phi$ is the angular position measured from the major axis. To account for the bearing’s own compliance, the profile was smoothed with a large radius arc ($R=350\text{ mm}$) in the axial plane.

The circular spline was modeled as a simple thick-walled ring to reduce mesh complexity, with an outer diameter of $d_{WG}=85 \text{ mm}$ and a width of $b_T=14 \text{ mm}$.

1.2 Material Properties and Finite Element Discretization

The flexspline material was specified as 32CrMnSiNiA, a high-strength alloy steel, with an elastic modulus of $E = 206 \text{ GPa}$ and a Poisson’s ratio of $\nu = 0.3$. The circular spline was assigned the properties of 45 steel ($E = 210 \text{ GPa}$, $\nu = 0.3$). All components were meshed with 10-node quadratic tetrahedral (C3D10) elements, which provide good accuracy for stress analysis in complex geometries. A finer mesh was applied to the flexspline’s tooth rim and critical fillet regions to capture high stress gradients.

1.3 Analysis Procedure

The analysis was performed in two sequential steps using different ABAQUS solvers to ensure efficiency and accuracy:

- Assembly Simulation (Implicit Static): The wave generator was translated radially into the flexspline until its nominal position was reached. This step determines the initial (pre-load) deformation and the associated assembly stresses in the flexspline before any torque is applied. The final state from this step serves as the initial condition for the next.

- Dynamic Operational Simulation (Explicit Dynamic): Starting from the assembled state, a constant rotational velocity was applied to the rigid wave generator. A resisting torque of $30 \text{ N·m}$ was applied to the circular spline, which was constrained from rotating, simulating a fixed output condition. The explicit dynamics method was chosen for its robustness in handling complex, transient contact conditions between the teeth of the flexspline and circular spline during high-speed operation.

All results are presented in a cylindrical coordinate system aligned with the flexspline’s axis. Radial deformation ($\omega$) is positive outward. Circumferential deformation ($v$) is positive in the direction opposite to the wave generator’s rotation. The angular coordinate $\phi$ starts from the major axis of the wave generator.

2. Results and Analysis: Assembly Phase

2.1 Initial Deformation of the Flexspline

The classical theoretical model for a perfectly flexible shell predicts the initial deformation of the flexspline neutral surface upon assembly with a perfect elliptical wave generator as:

$$\omega_{theory} = \omega_0 \cos(2\phi)$$

$$v_{theory} = \frac{\omega_0}{2} \sin(2\phi)$$

The FEM results, however, reveal deviations from this idealization due to the flexspline’s finite stiffness and the specific contact conditions. The cloud plots of deformation show that both radial and circumferential deformations attenuate along the length of the cup from the open end towards the closed bottom.

The quantitative comparison at the open end (where deformation is maximum) is critical. Table 2 summarizes the peak values and errors.

| Deformation Type | FEM Peak Value | Theoretical Peak Value | Location of Max. Error | Maximum Absolute Error | Maximum Error Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial ($\omega$) | 0.3543 mm | 0.285 mm | $\phi = 90°, 270°$ | 0.00762 mm | 2.6% |

| Circumferential ($v$) | 0.1790 mm | 0.1425 mm | $\phi \approx 45°, 135°$ | 0.00439 mm | 2.87% |

The analysis of the radial deformation error curve, $\delta_\omega(\phi) = \omega_{FEM}(\phi) – \omega_{theory}(\phi)$, shows a symmetric pattern. Crucially, the FEM radial deformation is larger than theory at the major axis ($\phi=0°, 180°$) and smaller at the minor axis ($\phi=90°, 270°$). This indicates that the flexspline does not perfectly conform to the wave generator profile; a small gap exists at the minor axis due to the shell’s bending stiffness. Similarly, the circumferential deformation error $\delta_v(\phi)$ shows a periodic pattern with phase shift, indicating that the points of zero circumferential displacement are not exactly at the axes. These discrepancies, while relatively small in magnitude (error rates under 3%), confirm that the classical deformation functions are approximations. The finite stiffness and 3D geometry of the actual strain wave gear flexspline necessitate numerical analysis for precise deformation prediction.

2.2 Assembly Stress Distribution

The press-fit assembly induces a complex, self-equilibrated stress field within the flexspline. The von Mises stress distribution shows a peak value of approximately $125.1 \text{ MPa}$. A more instructive decomposition reveals the nature of this stress. The maximum circumferential membrane stress (hoop stress, $\sigma_\theta$) is found to be $102.4 \text{ MPa}$, located on the outer surface near the junction of the tooth rim and the cylinder at the major axis. In contrast, the maximum circumferential shear stress ($\tau_{\theta z}$) in the same region is only $20.79 \text{ MPa}$. This confirms that the assembly stress state in the cylindrical region is dominated by hoop stresses caused by the radial squeezing action, rather than shear.

To understand the stress decay along the cup length, six representative cross-sections (I to VI) were analyzed, starting from the open end. The variation of hoop stress and shear stress at the neutral surface of these sections is plotted versus $\phi$.

The hoop stress ($\sigma_\theta$) decays monotonically and rapidly from the open end towards the closed bottom. The peak hoop stress values in sections IV, V, and VI are only about 10.8%, 5.6%, and 0.015% of the peak value near the rim, respectively. This rapid decay is characteristic of the “boundary effect” or “Saint-Venant’s principle” in shell structures.

The circumferential shear stress ($\tau_{\theta z}$) exhibits a more complex behavior. While also decaying overall, it shows a non-monotonic “transition zone” along the length. In sections closer to the open end, the shear stress is lower. It increases slightly in a middle section before decaying again towards the bottom. This phenomenon is attributed to the stiffening effect of the closed cup bottom and the mounting flange, which constrains the deformation and alters the local stress resultant path.

At the tooth rim itself (Section III), the stress distribution is heavily modulated by the discrete teeth. The hoop stress curve no longer follows a smooth $\cos(2\phi)$ pattern. Instead, it shows a high-frequency oscillation superimposed on the low-frequency wave, with a distinct “double-peak” phenomenon near the major axis. This is a direct result of the localized stiffness increase at each tooth root. The shear stress curve in the rim region shows even more severe and irregular fluctuations, particularly at the major axis, due to the highly discontinuous load path introduced by the meshing condition at assembly.

3. Results and Analysis: Dynamic Operational Phase

3.1 Dynamic Deformation Under Load

Under dynamic operating conditions, the deformation of the flexspline is no longer solely dictated by the wave generator’s profile. The time-varying, spatially uneven distribution of meshing forces between the flexspline and circular spline teeth significantly perturbs the deformation field. The dynamic radial deformation $\omega(\phi, t)$ at the neutral surface was extracted at five key instants during one wave generator cycle: start (0/1), quarter (1/4), half (1/2), three-quarters (3/4), and end (1/1) of the cycle.

The results show two clear trends. First, the amplitude of radial deformation increases progressively from the start to the end of the analyzed cycle within the transient dynamic simulation. This is attributed to the cumulative effect of inertial forces and the dynamic contact impact as the system reaches a steady cyclic state. Second, and more importantly, the shape of the radial deformation curve is altered. In certain angular regions, particularly where tooth engagement and disengagement occur, the curve exhibits local disturbances and no longer follows a perfect sinusoidal $\cos(2\phi)$ pattern. The classical elastic wave theory for the strain wave gear must therefore be supplemented with dynamic correction factors.

The dynamic circumferential deformation $v(\phi, t)$ shows analogous amplitude growth. Furthermore, the entire deformation curve experiences a slight upward shift (non-zero mean) and a small but consistent phase lag (angular shift) relative to the theoretical curve $v_{theory} \propto \sin(2\phi)$. This phase shift is the combined result of the load torque, which tends to “drag” the flexspline material, and the dynamic response lag due to inertia and damping in the contact interactions.

3.2 Dynamic Stress Evolution

The time-history of von Mises stress at a single material point on the neutral surface within each of the six cross-sections provides critical insight into fatigue risk. The results, plotted over one full cycle, reveal stark differences between the tooth rim and the cylindrical body.

In the rim sections (I, II, III), the stress fluctuates with large amplitude and high frequency. The maximum von Mises stress in the entire model, approximately $482.6 \text{ MPa}$, occurs in Section II. The stress-time curve in these sections distinctly shows four pronounced peaks per wave generator cycle. This corresponds to the four times per revolution that a given point on the flexspline passes through zones of maximum bending: near the major and minor axes of the elliptical deformation wave. The engagement and disengagement impacts with the circular spline teeth further modulate this signal, creating a complex, high-cycle fatigue loading pattern.

In contrast, the stress history in the cylindrical body sections (IV, V, VI) shows significantly lower amplitude and smoother fluctuations. The maximum stress in Section VI is only about $112.3 \text{ MPa}$, roughly 23% of the peak rim stress. The characteristic four-peak pattern is greatly attenuated, leaving a much smoother curve with minor disturbances mainly caused by stress waves propagating from the active rim region. This clear dichotomy confirms that the primary zone of fatigue concern in a cup-type strain wave gear is the tooth rim and its immediate vicinity, particularly the fillet region at the rim-cylinder junction.

The dynamic stress concentration can be summarized by the stress attenuation factor $\zeta$ along the cup length, defined as the ratio of the peak dynamic von Mises stress in a given section to the peak dynamic stress in Section II:

$$\zeta_i = \frac{\max(\sigma_{vm,i}(t))}{\max(\sigma_{vm,II}(t))}$$

The calculated factors are: $\zeta_I \approx 0.85$, $\zeta_{III} \approx 0.43$, $\zeta_{IV} \approx 0.31$, $\zeta_V \approx 0.27$, $\zeta_{VI} \approx 0.23$.

4. Conclusion

This investigation utilized a high-fidelity three-dimensional finite element model within ABAQUS to perform a sequential quasi-static and dynamic analysis of a cup-type strain wave gear. The study provides detailed insights that move beyond classical analytical approximations.

First, the assembly phase analysis validated the general form of the classical deformation functions but quantified non-negligible deviations (up to ~3% error) arising from the flexspline’s structural stiffness and 3D effects. It identified that assembly stresses are predominantly hoop stresses, which decay rapidly along the cup length. A transition zone for shear stress was observed, influenced by boundary constraints.

Second, the dynamic operational analysis revealed critical effects not captured by static or kinematic models. The deformation waves are perturbed by meshing forces, losing their perfect sinusoidal shape and acquiring a phase lag. Most significantly, the dynamic stress analysis uncovered a highly non-uniform fatigue loading environment. The tooth rim region experiences severe cyclic stress with four major peaks per revolution, while the cylindrical body is subject to much milder, attenuated stress fluctuations. This conclusively identifies the gear rim, especially the root transition area, as the most critical zone for fatigue-driven design optimization in a strain wave gear.

The presented methodology, combining implicit assembly simulation with explicit dynamic operation analysis, offers a robust framework for accurately predicting the service life and optimizing the geometry of strain wave gear components, ultimately contributing to more reliable and high-performance motion systems.