The quest for compact, high-ratio, and high-torque density speed reducers has been a persistent theme in mechanical engineering, particularly for demanding applications in robotics, aerospace, and heavy machinery. Among the various solutions, strain wave gearing, also known as harmonic drive, stands out for its exceptional precision, near-zero backlash, and high reduction ratios within a single stage. However, a fundamental challenge in conventional strain wave gear design is the inherent trade-off between the flexibility required for wave generation and the structural integrity needed for high torque capacity. The invention of the oscillating tooth strain wave gear presents a paradigm shift, decoupling the wave generation function from the load-bearing structure. This configuration fundamentally mitigates the stress-fatigue limitations associated with a flexible spline, paving the way for higher power transmission. This treatise delves into a critical structural enhancement for this novel drive: the adoption of non-symmetric tooth profiles in its meshing pairs. My analysis demonstrates that such a design can significantly increase the number of simultaneously engaged teeth, thereby further amplifying the power capacity of the oscillating tooth strain wave gear.

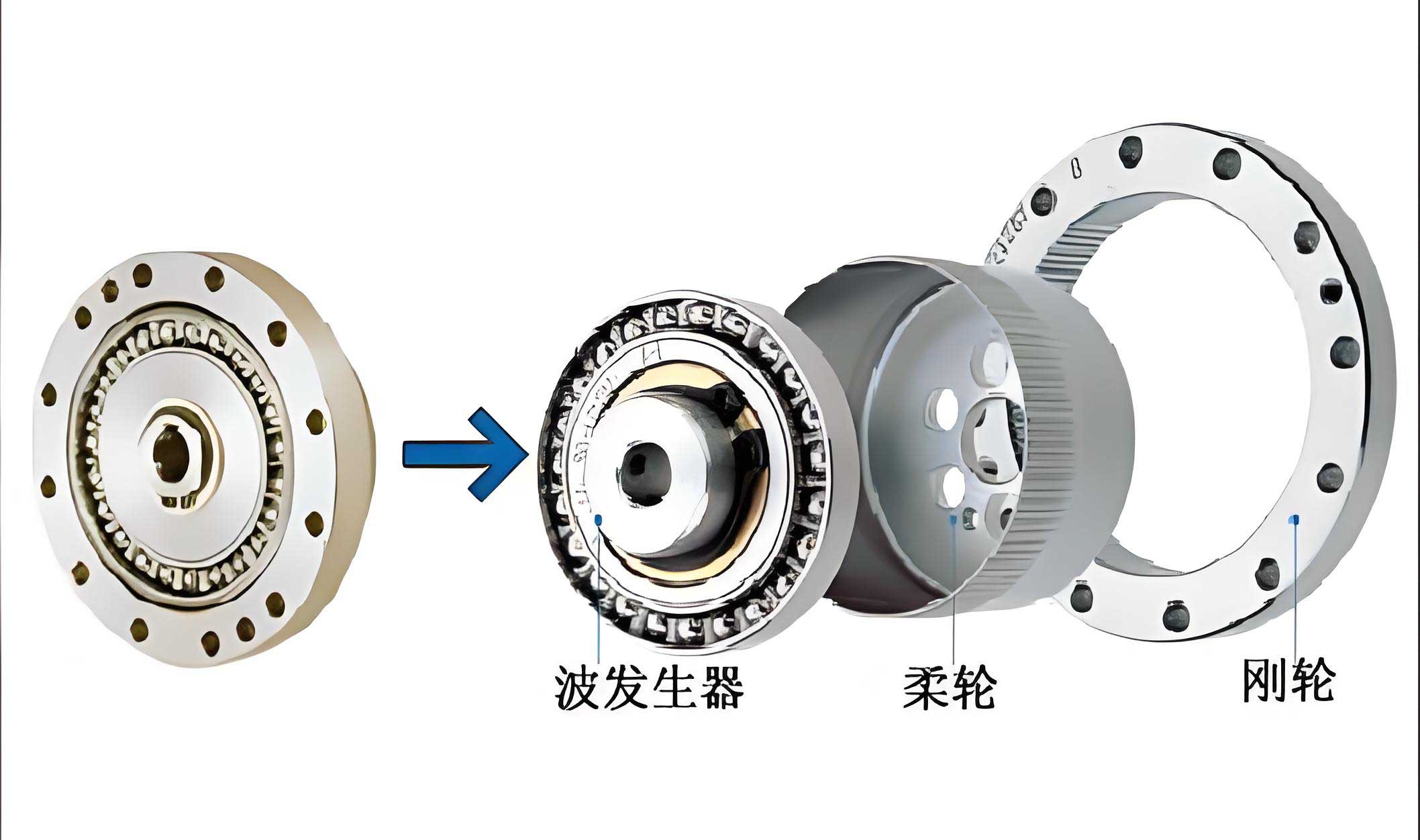

Before exploring the non-symmetric design, it is essential to understand the basic operating principle of the oscillating tooth strain wave gear. The system comprises four primary components: a rigid face gear (often the fixed component), a wave generator (typically the input), a set of oscillating teeth housed in radial slots, and a spline ring or carrier that constrains the oscillating teeth. Crucially, there are two distinct meshing pairs: Meshing Pair A between the wave generator and the rear flank of the oscillating teeth, and Meshing Pair B between the front flank of the oscillating teeth and the face gear. The unique kinematics are driven by the cam-like profile of the wave generator.

My detailed analysis of the meshing process reveals a distinct “work stroke” and “return stroke” for each oscillating tooth. As the wave generator rotates, its rising profile pushes an oscillating tooth radially outward (or inward, depending on the configuration). This motion is constrained by the engagement with the face gear’s tooth profile, forcing the oscillating tooth to move along it, which in turn imparts rotation to the spline ring (output). This constitutes the work stroke where power is transmitted. Once past the wave generator’s crest, the oscillating tooth is pushed back along a different path on the face gear tooth during the return stroke, which ideally transmits no useful torque. In a symmetric tooth design, the angular spans occupied by the work stroke and the return stroke on the wave generator are roughly equal.

This revelation is key: the wave generator’s rising flank performs the useful work, while its falling flank merely facilitates the return of the oscillating tooth. Therefore, a logical optimization is to extend the angular length of the rising (working) flank and shorten the falling (return) flank. This creates a “slow-in, fast-out” kinematic sequence for the oscillating teeth. Since the oscillating tooth strain wave gear transmits power through the simultaneous engagement of multiple teeth in these meshing pairs, elongating the working flank directly increases the number of teeth in the load-bearing zone at any given instant. Theoretically, with ideal frictionless conditions, a suitably designed non-symmetric profile could engage nearly all teeth in the transmission of torque. In practice, friction limits the feasible pressure angles, but a carefully engineered non-symmetric tooth form for the oscillating tooth strain wave gear nonetheless offers a substantial gain in load-sharing capability and overall power density.

The geometric relationship between the number of teeth on the face gear ($Z_E$) and the number of oscillating teeth ($Z_O$) defines two distinct operational regimes for the oscillating tooth strain wave gear, each influencing the viable non-symmetric tooth forms.

Analysis of Feasible Non-Symmetric Tooth Forms

The implementation of a non-symmetric profile depends critically on whether $Z_E > Z_O$ or $Z_E < Z_O$, as this determines on which side of the oscillating tooth the primary meshing forces act.

Case 1: $Z_E > Z_O$

In this configuration, the face gear and the wave generator engage on opposite sides of the oscillating tooth. The goal is to modify the standard symmetric tooth to have a longer working flank and/or a shorter return flank. Four conceptual non-symmetric tooth forms emerge from this principle, as summarized below.

| Tooth Form Sketch | Description | Feasibility |

|---|---|---|

| Extended Working Flank (Top) | The working flank (engaged with face gear) is elongated. The return flank (engaged with wave generator) remains standard. | Feasible. Increases load-sharing zone without structural conflict. |

| Extended Working Flank (Bottom) | The working flank (engaged with wave generator) is elongated. The return flank (engaged with face gear) remains standard. | Feasible. Increases load-sharing zone without structural conflict. |

| Shortened Return Flank (Top) | The return flank is significantly shortened, reducing the tooth’s base thickness. | Not Feasible. Leads to physical interference between adjacent oscillating teeth in their housing slots, requiring tooth removal which defeats the purpose of increasing engaged tooth count. |

| Shortened Return Flank (Bottom) | The return flank is significantly shortened, reducing the tooth’s base thickness. | Not Feasible. Leads to physical interference between adjacent oscillating teeth, similar to the form above. |

The critical issue with the shortened-return-flank designs is geometric interference. While the conjugate tooth profile on the face gear would adjust to the thinner oscillating tooth, the physical body of the oscillating tooth itself does not change in width. When the return flank is curtailed, the reduced material near the base can cause neighboring oscillating teeth to collide within their guiding slots, especially near the peak of engagement. This interference can only be resolved by removing every other oscillating tooth, which directly reduces the number of potentially load-bearing elements and negates the primary benefit of the non-symmetric design for the oscillating tooth strain wave gear.

Case 2: $Z_E < Z_O$

In this regime, the face gear and the wave generator engage on the same side of the oscillating tooth. Applying the same design logic of extending the working flank yields another set of four potential forms. A parallel analysis shows that the two forms involving a shortened return flank suffer from the same interference problems as in Case 1. Therefore, only the two forms featuring an extended working flank—where the tooth thickness is maintained or increased—are structurally viable for a practical oscillating tooth strain wave gear.

The conclusion is that for both major operational regimes of the oscillating tooth strain wave gear, only non-symmetric profiles created by extending the working flank are practically admissible. Profiles created by shortening the return flank introduce unacceptable interference.

Structural Condition for Correct Meshing with Non-Symmetric Teeth

Implementing a non-symmetric tooth is not merely a geometric exercise; it imposes a strict condition on the relationship between the wave generator and the face gear profiles for correct meshing. To derive this condition, I analyze the geometry on an imaginary cylindrical surface of radius $r$ that intersects the meshing interfaces.

Let $U$ be the wave number of the generator (typically 2). The arc length corresponding to one complete wave on the cylinder is:

$$ \overset{\frown}{S}_W = \frac{2\pi r}{U} $$

For a non-symmetric wave generator, I define a non-symmetry coefficient $\lambda_W$, which is the ratio of the arc length of its rising (working) flank to the total arc length of one wave:

$$ \overset{\frown}{S}_{W1} = \lambda_W \cdot \overset{\frown}{S}_W = \frac{2\lambda_W \pi r}{U} $$

Similarly, for the face gear with $Z_E$ teeth, the circular pitch (arc length per tooth) is:

$$ \overset{\frown}{S}_E = \frac{2\pi r}{Z_E} $$

I define the face gear’s non-symmetry coefficient $\lambda_E$ as the ratio of the arc length of its working tooth flank to the circular pitch:

$$ \overset{\frown}{S}_{E1} = \lambda_E \cdot \overset{\frown}{S}_E = \frac{2\lambda_E \pi r}{Z_E} $$

The kinematic requirement for correct meshing in the oscillating tooth strain wave gear is as follows: When the wave generator rotates through the angular span corresponding to its entire working flank ($\overset{\frown}{S}_{W1}$), an oscillating tooth must complete its traversal of the working flank of the face gear ($\overset{\frown}{S}_{E1}$). This ensures the tooth reaches the root of the face gear precisely as it reaches the peak of the wave generator. The overall motion ratio is governed by the standard transmission ratio of the strain wave gear. This kinematic compatibility must hold on our reference cylinder.

The fundamental gear relation for the oscillating tooth strain wave gear (with face gear fixed) is:

$$ \frac{\text{Rotation of Wave Generator}}{\text{Rotation of Spline Ring}} = \frac{Z_O}{Z_O – Z_E} $$

This ratio applies to full cycles. For the arcs corresponding to the working sections, the proportionality must be the same:

$$ \frac{\overset{\frown}{S}_{W1}}{\overset{\frown}{S}_{E1}} = \frac{\frac{2\lambda_W \pi r}{U}}{\frac{2\lambda_E \pi r}{Z_E}} = \frac{\lambda_W Z_E}{\lambda_E U} $$

This ratio must equal the ratio of the corresponding full-cycle arcs:

$$ \frac{\overset{\frown}{S}_{W}}{\overset{\frown}{S}_{E}} = \frac{\frac{2\pi r}{U}}{\frac{2\pi r}{Z_E}} = \frac{Z_E}{U} $$

For kinematic consistency, these two ratios must be equal:

$$ \frac{\lambda_W Z_E}{\lambda_E U} = \frac{Z_E}{U} $$

Simplifying this equation yields the critical Structural Condition for Correct Meshing:

$$ \boxed{\lambda_E = \lambda_W} $$

This elegant result states that for proper operation of a non-symmetric oscillating tooth strain wave gear, the non-symmetry coefficient of the face gear must be identical to the non-symmetry coefficient of the wave generator. Their working flanks must occupy the same proportional share of their respective characteristic periods (tooth pitch and wave length). This condition is independent of the specific tooth counts ($Z_E$, $Z_O$) and is fundamental to the design.

Constancy of Transmission Ratio with Non-Symmetric Teeth

A paramount requirement for any precision gear train, including the oscillating tooth strain wave gear, is the constancy of its instantaneous velocity ratio. Any fluctuation causes vibration, noise, and transmission error. It must be verified that the non-symmetric tooth form, under the condition $\lambda_E = \lambda_W$, does not compromise this vital characteristic.

The analysis employs two methods: the Willis (instant center) method for the equivalent mechanism and the direct differentiation of displacement relations. First, define key geometric parameters. Let $h$ be the theoretical lift of the wave generator (equal to the dedendum of the face gear). The average slope (angle) of the wave generator’s working flank, $\theta$, and the average pressure angle of the face gear’s working flank, $\alpha$, can be expressed as:

$$ \tan \theta = \frac{h U}{2\pi r \lambda_W}, \quad \tan \alpha = \frac{2\pi r \lambda_E}{Z_E h} $$

Using the Willis method for the planar equivalent linkage of the oscillating tooth strain wave gear, the relationship between the fundamental ratio $i_{WE}^{(H)}$ (wave generator to spline, face gear fixed) and the instantaneous ratio $i_{wh}^{(e)}$ can be derived. The result depends on the regime:

For $Z_E > Z_O$:

$$ i_{wh}^{(e)} = \frac{(\lambda_W U + \lambda_W Z_O – \lambda_E U)}{ \lambda_E Z_O} \cdot i_{WE}^{(H)} $$

For $Z_E < Z_O$:

$$ i_{wh}^{(e)} = \frac{(\lambda_E U + \lambda_W Z_O – \lambda_W U)}{ \lambda_E Z_O} \cdot i_{WE}^{(H)} $$

Now, applying the necessary structural condition $\lambda_E = \lambda_W$ derived above, both equations simplify dramatically:

For $Z_E > Z_O$:

$$ i_{wh}^{(e)} = \frac{(\lambda_W U + \lambda_W Z_O – \lambda_W U)}{ \lambda_W Z_O} \cdot i_{WE}^{(H)} = \frac{\lambda_W Z_O}{ \lambda_W Z_O} \cdot i_{WE}^{(H)} = i_{WE}^{(H)} $$

For $Z_E < Z_O$:

$$ i_{wh}^{(e)} = \frac{(\lambda_W U + \lambda_W Z_O – \lambda_W U)}{ \lambda_W Z_O} \cdot i_{WE}^{(H)} = \frac{\lambda_W Z_O}{ \lambda_W Z_O} \cdot i_{WE}^{(H)} = i_{WE}^{(H)} $$

Thus, in both regimes:

$$ \boxed{i_{wh}^{(e)} = i_{WE}^{(H)}} $$

This result is significant. It proves that under the condition $\lambda_E = \lambda_W$, the instantaneous velocity ratio of the non-symmetric oscillating tooth strain wave gear is constant and equal to its overall cycle-averaged ratio $i_{WE}^{(H)}$. This validates that the proposed non-symmetric design, when respecting the derived structural condition, maintains the smooth, constant-ratio transmission characteristic that is a hallmark of high-quality strain wave gearing. The kinematic performance is preserved while the potential load capacity is increased.

Summary of Design Implications and Advantages

The investigation into non-symmetric tooth profiles for the oscillating tooth strain wave gear reveals a clear path for performance enhancement. The primary motivation is to increase the number of teeth simultaneously engaged in the power-transmitting work stroke. This is achieved by elongating the working flank of the meshing profiles, effectively creating a “slow-in” phase for the oscillating teeth.

The viable non-symmetric tooth forms are strictly limited to those that extend the working flank, ensuring sufficient tooth body thickness to avoid inter-tooth interference within the guide slots. The two forms that shorten the return flank are structurally impractical for a dense array of oscillating teeth. The successful implementation is governed by a simple yet strict geometric law: the non-symmetry coefficients of the face gear and the wave generator must be equal ($\lambda_E = \lambda_W$). This ensures kinematic compatibility across the meshing pairs.

Most importantly, I have rigorously demonstrated that adherence to this condition guarantees a constant instantaneous velocity ratio, which is essential for the precision and smoothness expected from an advanced strain wave gear system. Therefore, the non-symmetric oscillating tooth strain wave gear represents a meaningful evolution of the concept, offering a direct method to scale torque capacity without sacrificing the fundamental kinematic virtues of strain wave gearing. It merges the high-ratio, compact advantages of traditional harmonic drives with a robust, multi-tooth engagement scheme more akin to planetary systems, culminating in a promising solution for high-power, high-precision applications.