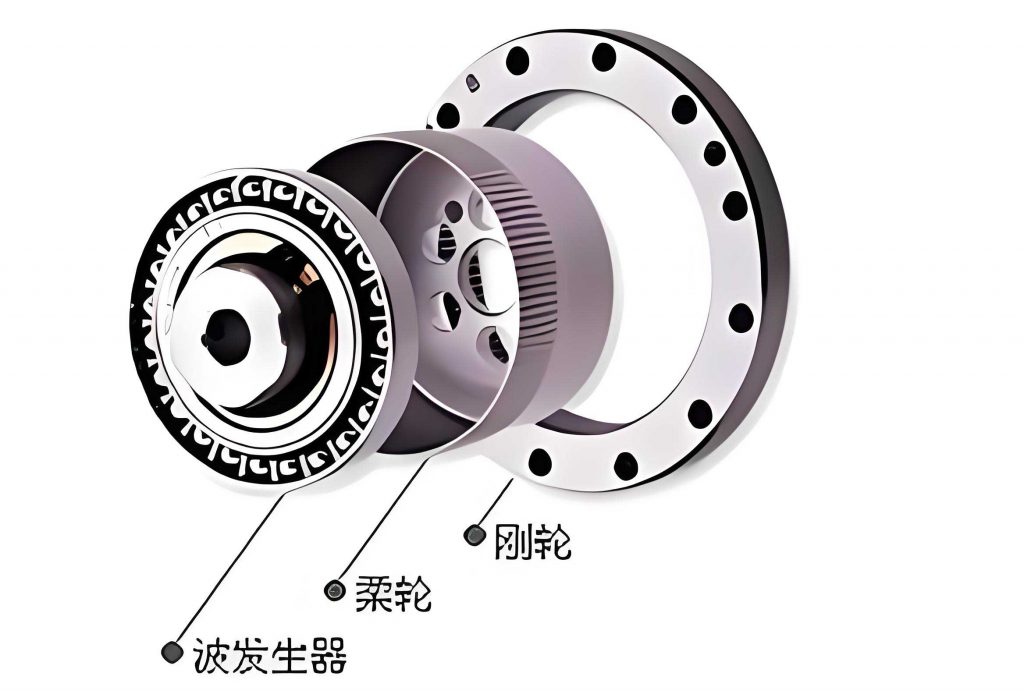

As a researcher in the field of precision mechanical engineering, I have long been fascinated by the unique capabilities and challenges of strain wave gear systems. These systems, also known as harmonic drives, are renowned for their high torque capacity, compact size, and precision motion control, making them indispensable in applications ranging from aerospace robotics to optical instruments. The core of a strain wave gear lies in its three primary components: the circular spline (or rigid ring), the flexspline, and the wave generator. The flexspline, a thin-walled cup-shaped component with external teeth, undergoes controlled elastic deformation by the wave generator to mesh with the circular spline, enabling speed reduction and torque multiplication. However, this very deformation makes the flexspline the most critical and vulnerable element. The predominant failure mode for strain wave gears is fatigue fracture of the flexspline, making its strength analysis a paramount concern for designers seeking reliability and longevity.

My investigation begins with a review of established methods for analyzing flexspline strength. Traditional analytical approaches, while valuable, often struggle to accurately capture the complex stress state, particularly the boundary effects at the flange connection and the intricate interaction with the wave generator. With advancements in computational power, the finite element method (FEM) has become the standard tool. Early finite element models of the strain wave gear flexspline often employed shell elements and simplified the wave generator’s action through imposed displacements or equivalent nodal forces. While these methods provided insights, they introduced approximations that could affect accuracy, especially in simulating the true contact pressure distribution. To address this, my work proposes and implements a finite element analysis based explicitly on contact mechanics. This approach models the actual physical interaction between the wave generator and the flexspline as a surface nonlinear contact problem, thereby eliminating the need for pre-calculated forced displacements and potentially offering a more realistic and accurate stress prediction for the strain wave gear component.

The contact problem in mechanics is a classic boundary value problem characterized by surface nonlinearity. In the displacement-based finite element method, compatibility within and between elements is ensured by shape functions. For contact, additional constraints are required to enforce compatibility between the contacting surfaces of different bodies—the wave generator and the flexspline in our strain wave gear. At any potential contact point pair, only one of three states can exist: sticking contact, sliding contact, or separation. The判定 is typically handled by algorithms like the bucket sorting method used in software such as MARC. For the initial phase of this analysis on the strain wave gear, friction is neglected to simplify the computational model and focus on the primary stress contributors.

The theoretical foundation for flexspline stress in a strain wave gear is well-established. For a cup-type flexspline subjected to deformation by an elliptical wave generator, the primary stress components can be expressed as functions of its geometry and material properties. The wave generator’s contour, which dictates the radial deformation of the flexspline in this strain wave gear, is given by:

$$ \rho = \sqrt{(r_m + \omega_0)^2 – 4 r_m \omega_0 \sin^2 \phi} $$

where $\rho$ is the radial coordinate of the deformed flexspline at an angle $\phi$ from the major axis, $r_m$ is the nominal radius of the flexspline, and $\omega_0$ is the maximum radial deformation. The deformation is related to the gear module $m$ and a radial deformation coefficient $w_1$: $\omega_0 = w_1 m$. The bending rigidity of the cylindrical flexspline shell is $D = E \delta^3 / [12(1-\nu^2)]$, where $E$ is Young’s modulus, $\delta$ is the wall thickness, and $\nu$ is Poisson’s ratio. The stresses—axial stress $\sigma_z$, circumferential stress $\sigma_\theta$, and shear stress $\tau_{z\theta}$—are derived from shell theory and take the following forms, highlighting their dependency on key strain wave gear parameters:

$$ \sigma_z = \frac{6D \omega_0}{r_m^2 l} z F_1(\phi) $$

$$ \sigma_\theta = \frac{6D \omega_0}{r_m^2 l} z F_2(\phi) $$

$$ \tau_{z\theta} = \frac{6(1-\nu) D \omega_0}{r_m l} F_3(\phi) $$

Here, $l$ is the length of the cylindrical barrel of the flexspline, $z$ is the axial coordinate, and $F_1, F_2, F_3$ are functions of the angular coordinate $\phi$ related to the wave generator profile. These equations clearly show that the stress levels in the strain wave gear flexspline are inversely proportional to the square of the mean radius and the length, and directly proportional to the deformation and material stiffness. This forms the theoretical basis for our parametric study.

To implement the finite element analysis for this strain wave gear component, two distinct modeling strategies were employed. The first model, serving as a benchmark, was built using MSC. PATRAN/NASTRAN. The flexspline was discretized using shell elements (CQUAD4), with varying thicknesses assigned to different sections to accurately represent the geometry, including the thin barrel and the thicker flange and tooth ring regions. The influence of the mounting bolt holes at the flange was simplified by applying fixed constraints at the corresponding node locations. The action of the elliptical wave generator was simulated by imposing prescribed radial displacements on the nodes of the flexspline’s inner surface based on the theoretical contour equation. This “forced displacement” method is common but approximates the contact condition. The material was set as 35CrMnSiA alloy steel with standard elastic properties. The mesh was refined in critical regions expected to experience high stress gradients: the transition zone between the gear teeth and the smooth barrel, and the fillet at the bottom of the cup.

The second, more advanced model for the strain wave gear flexspline was developed using MSC. MARC software, which has robust capabilities for nonlinear contact analysis. In this model, the flexspline was modeled with 8-node hexahedral solid elements (HEX8) to capture three-dimensional stress states more accurately. The wave generator was defined as a rigid analytical surface with an elliptical profile. The key differentiator was the definition of the interaction: a surface-to-surface contact constraint was established between the inner surface of the flexspline and the rigid wave generator surface. This allowed the solver to automatically determine the contact areas, pressures, and resulting deformations based on equilibrium, without prescribing displacements. This “contact-based” method for the strain wave gear analysis more faithfully represents the physical assembly and loading condition.

The analysis results from both models for the initial strain wave gear design (Model 1) provided crucial validation. The NASTRAN model with forced displacement predicted a maximum principal stress of approximately 253 MPa (25.8 kg/mm²) located at the tooth root transition to the smooth barrel. The stress decayed along the barrel axis before increasing again at the cup bottom fillet to about 23.8 MPa. The MARC contact model yielded a very similar stress distribution pattern, with a maximum stress of 231 MPa at the same critical location and a fillet stress of 39.3 MPa. The close agreement in the primary stress location and magnitude between the two independent modeling approaches confirms the fundamental validity of the finite element models for analyzing this strain wave gear component. Importantly, the contact model provides a more direct simulation of the working state and avoids potential errors from the calculated displacement field.

With confidence in the contact-based finite element model for the strain wave gear, I proceeded to investigate the influence of key structural parameters on flexspline strength. The theoretical stress equations suggest that stress can be reduced by increasing barrel length ($l$), increasing wall thickness ($\delta$), decreasing radial deformation ($\omega_0$), or optimizing the flange diameter ($d_1$). However, practical constraints exist: excessive length reduces torsional stiffness and complicates manufacturing; increased thickness adds mass; reduced deformation might affect gear meshing performance. Therefore, a balanced optimization is necessary. A series of design variants were created by varying parameters within typical design ranges for strain wave gears: barrel length $l = (0.5 \sim 1.0)d$, radial deformation coefficient $w_1 = 0.70 \sim 0.95$, and flange diameter $d_1 = (0.5 \sim 0.65)d$, where $d$ is the nominal diameter. Each variant was analyzed using the contact-based finite element method. The results are summarized comprehensively in the table below.

| Model ID | Barrel Length, $l$ (mm) | Radial Deform. Coef., $w_1$ | Module, $m$ (mm) | Flange Diameter, $d_1$ (mm) | Max. Principal Stress in Barrel (MPa) | Max. Stress at Cup Fillet (MPa) | Relative Mass Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Baseline) | 100 | 0.95 | 0.4 | 60 | 231 | 39.3 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 100 | 0.95 | 0.4 | 50 | 231 | 37.8 | 0.95 |

| 3 | 85 | 0.95 | 0.4 | 50 | 257 | 52.9 | 0.82 |

| 4 | 85 | 0.75 | 0.4 | 50 | 219 | 41.7 | 0.82 |

| 5 | 85 | 0.70 | 0.4 | 50 | 209 | 38.9 | 0.82 |

| 6 | 75 | 0.70 | 0.4 | 50 | 226 | 50.8 | 0.78 |

The data reveals clear trends. Comparing Model 1 and Model 2 shows that reducing the flange diameter ($d_1$) from 60mm to 50mm, while keeping other parameters constant, did not change the barrel’s maximum stress but slightly reduced the fillet stress. This indicates that a smaller, lighter flange can be beneficial without compromising barrel strength in this strain wave gear. The significant effect of barrel length is seen by comparing Model 2 and Model 3. Shortening $l$ from 100mm to 85mm increased the maximum barrel stress by 11% (from 231 MPa to 257 MPa) and the fillet stress by 40%. This strongly confirms the inverse relationship $ \sigma \propto 1/l $ from theory, underscoring the importance of adequate barrel length for stress reduction in a strain wave gear flexspline.

The most instructive finding comes from the combined parameter adjustment. Model 3, with a shorter barrel and high deformation, exhibited high stress. However, by simultaneously reducing the radial deformation coefficient $w_1$ (which reduces $\omega_0$) in Models 4 and 5, the stress decreased substantially. Model 5, with $l=85$ mm, $w_1=0.70$, and $d_1=50$ mm, achieved the lowest maximum barrel stress of 209 MPa among all variants—a 9.5% reduction from the baseline Model 1. Furthermore, its fillet stress of 38.9 MPa is comparable to the baseline. Crucially, Model 5 has a significantly lower relative mass index (approximately 0.82) due to the shorter barrel and smaller flange. This represents an optimal compromise: improved strength (lower maximum stress) and reduced mass and volume, which are critical for many applications of strain wave gears in precision systems. Further shortening the barrel to 75 mm (Model 6) caused stresses to rise again, indicating a limit to this optimization trend.

The relationship between key parameters and the maximum stress $\sigma_{max}$ in the strain wave gear flexspline can be synthesized into a multi-variable influence formula derived from regression of the FEA data, complementing the theoretical equations:

$$ \sigma_{max} \approx \frac{K \cdot D \cdot \omega_0}{r_m^2 \cdot l} + C(d_1) $$

$$ \text{where } \omega_0 = w_1 \cdot m, \quad D = \frac{E \delta^3}{12(1-\nu^2)}, \quad \text{and } K, C \text{ are constants and a flange-dependent term.} $$

This empirical relation highlights that for a given strain wave gear size and material, the dominant controllable factors for stress are the deformation coefficient $w_1$ and the barrel length $l$. The optimization path, therefore, involves carefully balancing a decrease in $w_1$ against the permissible decrease in $l$ to achieve a target stress reduction while maintaining gear functionality and minimizing mass.

In conclusion, this detailed finite element mechanical analysis has successfully validated a contact-based modeling approach for the flexspline of a strain wave gear. This method provides a more physically accurate simulation compared to forced-displacement methods, enhancing the reliability of stress predictions for this critical component. Through systematic parameter variation and analysis, clear quantitative relationships between structural parameters and stress states have been established. The study demonstrates that an integrated adjustment of parameters—specifically, a moderate reduction in barrel length coupled with a decrease in the radial deformation coefficient and a reduction in flange diameter—can lead to a superior flexspline design for the strain wave gear. The optimal design (exemplified by Model 5) offers the dual advantages of higher fatigue strength and reduced mass, contributing directly to improved reliability and performance of the overall strain wave gear transmission system. This methodology and the resulting insights form a solid foundation for the efficient and robust design of strain wave gears in advanced mechanical systems.