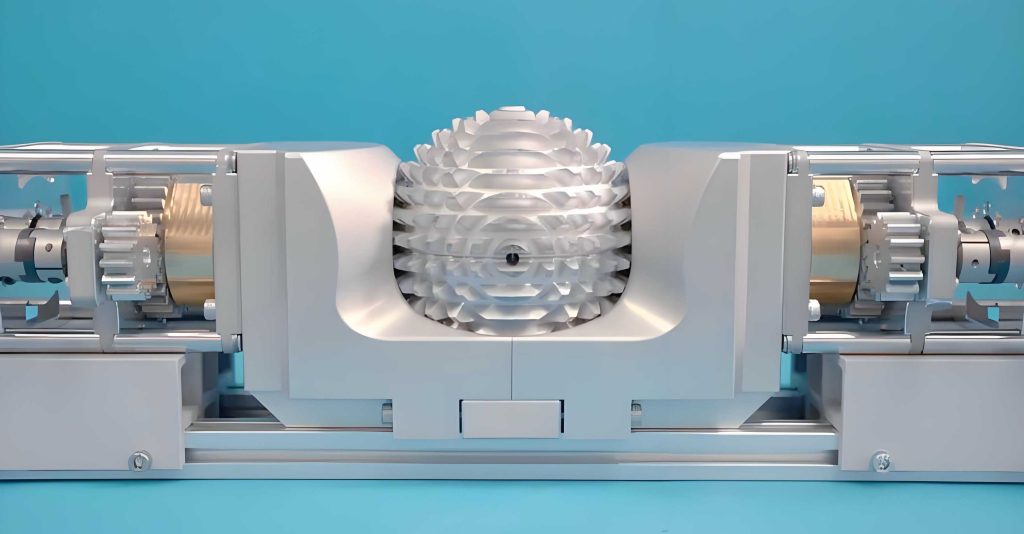

In the pursuit of advanced gearing solutions for compact, high-torque transmissions with intersecting or non-parallel axes, the spherical gear concept offers a unique geometry. Traditional spur-type spherical gears, characterized by radial arc-shaped tooth traces, provide the capability for variable-axis-angle transmission. However, they often suffer from limitations such as lower load capacity due to limited contact lines and high sensitivity to assembly errors, which can drastically shift the contact pattern and induce vibration. This work introduces the helical tooth form to the spherical gear geometry, creating the spherical helical gear. The primary objectives are to enhance meshing continuity, increase load-sharing capacity, and systematically manage transmission error through intentional tooth flank modification, thereby improving performance and robustness against misalignments.

The fundamental geometry of a spherical gear can be envisioned as a cylindrical gear whose tooth traces are arcs lying on a sphere centered at the gear’s mid-plane. This allows for three primary meshing configurations: convex-convex, convex-concave, and convex-cylindrical (or convex-oblique) types. While previous research has established generation methods and contact analysis for spur spherical gears, the incorporation of a helix angle and the application of controlled modifications remain underexplored. This paper presents a comprehensive methodology, from the mathematical modeling of the tooth surface generated by a modified imaginary rack-cutter to a detailed Tooth Contact Analysis (TCA) that includes assembly errors. The goal is to demonstrate that helical tooth traces, combined with parabolic profile modification, can yield a contact pattern along the helix, a parabolic transmission error function, and significantly reduced sensitivity to installation inaccuracies.

1. Geometric Foundation and Mathematical Model

The tooth surface of the spherical helical gear is derived using the theory of gearing and the envelope of a family of surfaces generated by a tool. We employ an imaginary rack-cutter as the generating tool. To enable controlled modification, a parabolic curve is superimposed on the standard straight-sided rack profile in its normal section.

1.1 Profile of the Modified Imaginary Rack-Cutter

In the normal section coordinate system \( S_a(O_a-x_a, y_a, z_a) \), the position vector of a point on the rack-cutter profile, denoted by parameter \( u_c \), is given by:

$$

\mathbf{r}_a(u_c) = \begin{bmatrix}

u_c \cos \alpha_n – a_c u_c^2 \sin \alpha_n – d_p \cos \alpha_n \\

-u_c \sin \alpha_n + a_c u_c^2 \cos \alpha_n + a_m + d_p \sin \alpha_n \\

0 \\

1

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where:

\( \alpha_n \) is the normal pressure angle.

\( a_m = \pi m_n / 4 \) is half of the normal pitch (\( m_n \) is normal module).

\( a_c \) is the parabolic modification coefficient.

\( d_p \) defines the pole position of the parabolic curve.

This profile is then positioned to form the helical rack-cutter surface. The coordinate systems are defined as follows: \( S_b \) is an auxiliary frame, and \( S_c \) is attached to the rack-cutter. The rack surface is generated by sweeping the profile along a helix. The transformation involves a rotation by an angle \( \theta_a \) and accounting for the base helix angle \( \beta \). The position vector in \( S_c \) is:

$$

\mathbf{r}_c(u_c, \theta_a) = \mathbf{M}_{cb}(\beta) \mathbf{M}_{ba}(\theta_a) \mathbf{r}_a(u_c)

$$

Here, \( \mathbf{M}_{cb} \) and \( \mathbf{M}_{ba} \) are homogeneous transformation matrices. The pitch radius of this imaginary rack, equivalent to the gear’s pitch radius, is \( R_a = 0.5 m_n z_w \), where \( z_w \) is the number of teeth of the workgear.

1.2 Generation of the Spherical Helical Gear Tooth Surface

The generation process for a spherical helical gear simulates the meshing of the imaginary rack-cutter and the gear blank. The key difference from a standard helical gear is the requirement for a synchronized radial and axial feed of the cutter to generate the spherical (arc-shaped) tooth trace. For a CNC gear hobbing or shaping machine, this translates into a controlled compound motion. The relationship between the cutter rotation \( \phi_h \) and the workgear rotation \( \phi_w \) is:

$$

\phi_w = \frac{z_h}{z_w} \phi_h + \Delta \phi_w, \quad \text{with} \quad \Delta \phi_w = \frac{l_z \tan \beta}{R_a}

$$

where \( z_h \) is the number of cutter starts (e.g., hob threads), and \( l_z \) is the axial feed.

To derive the equation of the generated gear tooth surface \( \Sigma_1 \), we consider the coordinate systems: \( S_c \) (cutter), \( S_d \) (fixed), and \( S_1 \) (gear). During generation, as the gear rotates through angle \( \phi_1 \), the rack translates by a distance \( r_{p1} \phi_1 \) along its pitch line, where \( r_{p1} \) is the pitch radius of gear 1. According to the theory of gearing, at the point of contact, the common normal vector must intersect the instantaneous axis of rotation (pitch line I-I). This condition yields the equation of meshing:

$$

\frac{X_c – x_c}{n_{c_x}} = \frac{Y_c – y_c}{n_{c_y}} = \frac{Z_c – z_c}{n_{c_z}}

$$

Here, \( (X_c, Y_c, Z_c) \) are coordinates of a point on the instantaneous axis in \( S_c \), \( (x_c, y_c, z_c) \) are coordinates of the contact point, and \( (n_{c_x}, n_{c_y}, n_{c_z}) \) are components of the unit normal at the contact point. For the rack generation process, \( X_c = 0 \) and \( Y_c = r_{p1} \phi_1 \). Using the first equality, the generation angle \( \phi_1 \) is solved as a function of the surface parameters:

$$

\phi_1(u_c, \theta_a) = \frac{n_{c_x} y_c(u_c, \theta_a) – n_{c_y} x_c(u_c, \theta_a)}{n_{c_x} r_{p1}}

$$

The tooth surface of gear 1 in its own coordinate system \( S_1 \) is then obtained by the coordinate transformation:

$$

\mathbf{r}_1(u_c, \theta_a) = \mathbf{M}_{1c}(\phi_1(u_c, \theta_a)) \mathbf{r}_c(u_c, \theta_a)

$$

$$

\mathbf{n}_1(u_c, \theta_a) = \mathbf{L}_{1c}(\phi_1(u_c, \theta_a)) \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_c}{\partial \theta_a} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_c}{\partial u_c}

$$

where \( \mathbf{M}_{1c} \) is the homogeneous transformation matrix and \( \mathbf{L}_{1c} \) is its 3×3 rotational submatrix.

A critical aspect of designing a spherical gear pair is the combination of generating tools. For a conjugate convex-concave pair, both gears can be generated by the same rack-cutter, theoretically resulting in line contact. For convex-convex and convex-cylindrical pairs, different cutters (or cutter settings) are required for each member, inherently leading to point contact. In this study, we apply parabolic profile modification (via \( a_c \neq 0 \)) primarily to the pinion (convex member). This intentional mismatch transforms even a theoretically line-contact convex-concave pair into a favorable point contact with a controlled transmission error, which is essential for absorbing linear errors caused by misalignments and reducing edge loading.

2. Tooth Contact Analysis (TCA) Model with Assembly Errors

Tooth Contact Analysis is a computational simulation of the meshing of two gear teeth, based on the conditions of continuous tangency of the mating surfaces. It predicts the contact path, transmission error, and the influence of misalignments.

2.1 Basic TCA Equations

Consider two gear tooth surfaces \( \Sigma_1 \) and \( \Sigma_2 \) rotating about fixed axes. Their positions and orientations are defined in a fixed global coordinate system \( S_h \). The condition for continuous contact is that at any instant, there exists a point where the position vectors and the unit normals of both surfaces coincide in \( S_h \).

Let \( \mathbf{r}_1(u_1, \theta_1) \) and \( \mathbf{n}_1(u_1, \theta_1) \) be the pinion surface, and \( \mathbf{r}_2(u_2, \theta_2) \) and \( \mathbf{n}_2(u_2, \theta_2) \) be the gear surface. Their representations in \( S_h \), as functions of their respective rotation angles \( \phi_1 \) and \( \phi_2 \), are:

$$

\mathbf{r}_h^{(1)}(u_1, \theta_1, \phi_1) = \mathbf{M}_{h1}(\phi_1) \mathbf{r}_1(u_1, \theta_1)

$$

$$

\mathbf{n}_h^{(1)}(u_1, \theta_1, \phi_1) = \mathbf{L}_{h1}(\phi_1) \mathbf{n}_1(u_1, \theta_1)

$$

$$

\mathbf{r}_h^{(2)}(u_2, \theta_2, \phi_2) = \mathbf{M}_{h2}(\phi_2) \mathbf{r}_2(u_2, \theta_2)

$$

$$

\mathbf{n}_h^{(2)}(u_2, \theta_2, \phi_2) = \mathbf{L}_{h2}(\phi_2) \mathbf{n}_2(u_2, \theta_2)

$$

The tangency conditions in \( S_h \) are:

$$

\mathbf{r}_h^{(1)}(u_1, \theta_1, \phi_1) = \mathbf{r}_h^{(2)}(u_2, \theta_2, \phi_2)

$$

$$

\mathbf{n}_h^{(1)}(u_1, \theta_1, \phi_1) = \mathbf{n}_h^{(2)}(u_2, \theta_2, \phi_2)

$$

Equation (2) represents a system of six scalar equations. However, since the normals are unit vectors, only five equations are independent. The unknowns are the four surface parameters \( (u_1, \theta_1, u_2, \theta_2) \) and the gear rotation angle \( \phi_2 \), with \( \phi_1 \) as the input parameter. Solving this nonlinear system for a sequence of \( \phi_1 \) values yields the path of contact points.

2.2 Modeling of Assembly Errors

The transformation matrices \( \mathbf{M}_{h1} \) and \( \mathbf{M}_{h2} \) encapsulate the assembly configuration. To model errors, we introduce intermediate coordinate systems. For the gear (member 2), a misalignment coordinate system \( S_v \) is used to model a horizontal offset error \( \Delta C \) (change in center distance) and a vertical misalignment angle \( \Delta \gamma_v \) (error in shaft angle). The composite transformation is built step-by-step. For the pinion, a similar approach can incorporate axial positioning errors. The general form becomes:

$$

\mathbf{M}_{h1} = \mathbf{M}_{hv} \mathbf{M}_{vk} \mathbf{M}_{k1}(\phi_1)

$$

$$

\mathbf{M}_{h2} = \mathbf{M}_{hf} \mathbf{M}_{f2}(\phi_2)

$$

Where matrices like \( \mathbf{M}_{hv} \) contain the error terms \( \Delta C \) and \( \Delta \gamma_v \).

2.3 Transmission Error and Contact Ellipse

The transmission error (TE) is defined as the deviation of the gear’s actual position from its position in a perfectly conjugate (rigid) motion:

$$

\delta \phi_2(\phi_1) = \left( \phi_2(\phi_1) – \phi_2^0 \right) – \frac{z_1}{z_2} \left( \phi_1 – \phi_1^0 \right)

$$

where \( \phi_1^0, \phi_2^0 \) are the initial engagement angles, and \( z_1, z_2 \) are the tooth numbers. A parabolic TE function is desirable as it is continuous and can accommodate small misalignments without introducing discontinuities that cause vibration.

At each contact point, the instantaneous contact is an ellipse, approximated by the principal curvatures and directions of the two surfaces. The size and orientation of this contact ellipse are calculated. For visualization of the contact pattern (bearing pattern) on the tooth flank, points along the major axis of this ellipse within its calculated length are projected onto the gear’s surface.

3. Computational Results and Parametric Studies

We analyze three types of spherical helical gear pairs with the basic design parameters listed in Table 1. The pinion (convex type) is always generated with a parabolic modification (\( a_c = 0.005 \)).

| Parameter | Pinion (Convex) | Gear (Concave/Convex/Cylindrical) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Teeth, \( z \) | 35 | 60 |

| Normal Module, \( m_n \) (mm) | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Normal Pressure Angle, \( \alpha_n \) (°) | 20 | 20 |

| Helix Angle at Ref., \( \beta \) (°) | 30 | 30 |

| Shaft Angle, \( \Sigma \) (°) | 25 | 25 |

| Face Width, \( B \) (mm) | 10 | 10 |

| Addendum Coefficient | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Dedendum Coefficient | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| Modification Coeff., \( a_c \) | 0.005 | 0 |

3.1 Contact Patterns and Transmission Error for Nominal Conditions

The TCA results for the three pairs under perfect assembly conditions are summarized below.

Convex-Concave Pair: The contact pattern is a line oriented along the helical tooth trace, similar to a standard parallel-axis helical gear but curved to follow the spherical flank. This significantly increases the contact ratio compared to a spur spherical gear. The transmission error is nearly zero, indicating a highly conjugate action. The theoretical line contact is slightly broken into an elongated elliptical pattern due to the pinion modification, providing a safety margin against edge contact.

Convex-Convex Pair: This configuration yields a point contact. The modification produces a clean, localized elliptical contact patch and a controlled parabolic transmission error with a small amplitude (approx. 10 arc-seconds in the example). The formula governing the parabolic error can be approximated as \( \delta \phi_2 \approx -K_a a_c \phi_1^2 \), where \( K_a \) is a geometry-dependent constant.

Convex-Cylindrical (Oblique) Pair: This also results in point contact. The contact ellipse is generally smaller than in the convex-convex case for the same helix angle. The transmission error is parabolic but with a larger amplitude (approx. 19.5 arc-seconds), indicating a higher level of intentional mismatch for this geometry. The relationship between contact ellipse dimensions and principal curvatures is given by:

$$

a_e = \mu \sqrt{\frac{\delta}{|\kappa_{\Sigma}|}}, \quad b_e = \mu \sqrt{\frac{\delta}{|\kappa_{\Sigma}|}} \left( \frac{|\kappa_{\Pi}|}{|\kappa_{\Sigma}|} \right)^{1/2}

$$

where \( a_e, b_e \) are the major and semi-minor axes, \( \delta \) is the normal approach (load-dependent), \( \kappa_{\Sigma} \) and \( \kappa_{\Pi} \) are the relative normal curvatures in principal directions, and \( \mu \) is a material constant.

| Gear Pair Type | Contact Type | Contact Pattern Orientation | Transmission Error Shape | Typical TE Amplitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convex-Concave | Line→Elliptical | Along Helix | ~Zero / Flat | < 1 arc-sec |

| Convex-Convex | Elliptical (Point) | Diagonal | Parabolic | ~10 arc-sec |

| Convex-Cylindrical | Elliptical (Point) | Diagonal | Parabolic | ~20 arc-sec |

3.2 Influence of Helix Angle

The helix angle \( \beta \) is a critical design parameter for the spherical helical gear. Its effects are multi-faceted:

$$

\text{Contact Ratio} \propto \frac{B \tan \beta}{p_t} + \text{(spur component)}

$$

where \( p_t \) is the transverse pitch. Increasing \( \beta \) directly increases the overlap ratio. However, it also influences the contact mechanics:

- Ellipse Size: The contact ellipse major axis length generally decreases with increasing \( \beta \), potentially increasing contact stress if not compensated by a wider face width.

- Ellipse Orientation: The ellipse becomes more skewed (diagonal) as \( \beta \) increases, which can affect lubrication film formation and wear patterns.

- Axial Thrust: Like standard helical gears, spherical helical gears generate axial forces \( F_a = F_t \tan \beta \), which must be accommodated by the bearing system.

Therefore, selecting \( \beta \) involves a trade-off between high contact ratio (good for quietness and load sharing) and acceptable contact ellipse geometry/lubrication.

3.3 Sensitivity to Assembly Errors

A key advantage of applying modification is to desensitize the gear pair to misalignments. We analyze the effect of combined error \( \Delta \gamma_v = 0.2° \) and \( \Delta C = 0.2 \) mm. Table 3 summarizes the shift in contact pattern compared to the spur version (\( \beta = 0° \)).

| Gear Pair Type | Helix Angle β | Contact Pattern Shift (Direction) | Sensitivity Relative to Spur Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Types | 0° (Spur) | Significant shift, often to one edge | Baseline (High) |

| Convex-Concave | 30° | Moderate shift along helix | Reduced |

| Convex-Convex | 30° | Small shift, ellipse remains centered | Greatly Reduced |

| Convex-Cylindrical | 30° | Small shift, ellipse remains centered | Greatly Reduced |

The parabolic modification in the point-contact pairs (convex-convex, convex-cylindrical) is particularly effective. The designed parabolic transmission error curve has the capacity to “absorb” a limited amount of linear transmission error induced by misalignment, preventing a discontinuous jump in the TE function that causes vibration. The relationship can be expressed as the modified TE being more tolerant to a change in the mean mesh position \( \Delta \phi_{mesh} \):

$$

\delta \phi_{2, \text{modified}}(\phi_1 + \Delta \phi_{mesh}) \approx \delta \phi_{2, \text{nominal}}(\phi_1) + C \cdot \Delta \phi_{mesh}

$$

where the constant \( C \) is smaller for a well-modified pair than for an unmodified one, indicating lower sensitivity.

4. Discussion: Design Implications and Optimization

The introduction of the helix to the spherical gear topology opens a new design space. The analysis shows that the convex-concave type offers the highest potential load capacity due to its elongated contact line, making it suitable for high-power, low-noise applications where precise alignment can be maintained. The convex-convex and convex-cylindrical types, with their point contact and low sensitivity, are advantageous in applications where robustness to mounting errors or housing deflection is critical, such as in aerospace or automotive auxiliary drives.

The modification coefficient \( a_c \) is a powerful design variable. It directly controls the amplitude of the parabolic transmission error:

$$

\text{TE Amplitude} \propto a_c \cdot (z_1 / z_2)^2 \cdot f(\beta, \alpha_n)

$$

Selecting \( a_c \) involves balancing the need for misalignment absorption (requiring a larger amplitude) against the desire for minimal kinematic error under nominal conditions. A multi-objective optimization can be formulated to find \( (a_c, \beta, \text{face width}) \) that minimizes contact stress and TE sensitivity while maximizing contact ratio, subject to geometric and manufacturing constraints.

Furthermore, the generation model presented is readily adaptable to modern CNC gear manufacturing. The synchronized motions for creating the spherical tooth trace—simulated in the model by the coordinated rotation and translation of the imaginary rack—can be directly programmed as the interdependent axes movements of a multi-axis gear hobber or grinder.

5. Conclusion

This study has presented a comprehensive methodology for the design and analysis of spherical helical gears. By integrating a helix angle into the spherical gear geometry and applying controlled parabolic flank modification, significant performance enhancements are achieved over traditional spur spherical gears.

- The helical tooth form produces a contact path along the tooth trace, dramatically increasing the contact ratio and, consequently, the smoothness and potential load-carrying capacity of the gear pair, particularly in the convex-concave configuration.

- Tooth flank modification, implemented via a parabolic rack-cutter profile, is essential for managing the meshing characteristics. For theoretically line-contact pairs, it introduces a benign point contact to prevent edge loading. For point-contact pairs, it creates a predictable parabolic transmission error function.

- The parabolic transmission error is a key feature for improving noise-vibration-harshness (NVH) performance. It provides a continuous motion transfer and possesses the capacity to absorb small linear errors caused by assembly misalignments without generating discontinuous accelerations that excite vibration.

- The developed TCA model, incorporating assembly errors such as shaft angle deviation and center distance error, demonstrates that the proposed spherical helical gear designs, especially the modified convex-convex and convex-cylindrical types, exhibit markedly reduced sensitivity to such errors compared to their unmodified or spur counterparts. This translates to more stable contact patterns and consistent performance under real-world manufacturing and assembly tolerances.

- The helix angle is a crucial trade-off parameter. While it boosts contact ratio, it also affects contact ellipse size, orientation, and axial thrust forces. An optimal design must balance these factors based on the specific application requirements for load, noise, efficiency, and robustness.

In summary, the spherical helical gear with controlled modification represents a sophisticated gearing solution for intersecting and non-parallel shaft applications where high performance, compactness, and reliability are paramount. The mathematical framework and analysis tools provided here form a foundation for the further optimization and practical implementation of this advanced gear type.