In my experience working with industrial machinery, particularly in pulp and paper production systems, I have frequently encountered the critical role played by cycloidal drives, specifically planetary cycloidal gear speed reducers. These reducers are essential for transmitting torque with high efficiency and precision, often in harsh operating environments. A key component within such a cycloidal drive is the eccentric bearing sleeve, which houses the rolling bearings and generates the necessary oscillatory motion for the cycloidal disc. However, a specialized variant—the 180° double partial bearing sleeve—presents significant manufacturing challenges due to its high-precision dual eccentricity. The quality of this sleeve directly impacts the longevity and reliability of the entire cycloidal drive system; poor manufacturing can lead to frequent failures, unscheduled downtime, and substantial production losses. Based on practical shop-floor constraints and the need for enhanced efficiency, I have developed and implemented a dedicated processing tooling for machining this sleeve. This article details the design rationale, operational principles, and step-by-step methodology from a first-person perspective, incorporating tables and formulas to encapsulate the technical nuances.

The fundamental operation of a cycloidal drive hinges on the kinematic interaction between an eccentric input, cycloidal discs, and a stationary ring of pins. The double partial bearing sleeve is a core element that facilitates this motion. Its design features two external cylindrical surfaces, each intended for bearing mounting, which are eccentrically offset relative to the internal bore by an equal magnitude but oriented 180° apart. The machining tolerances are stringent: the external diameters must conform to a k6 tolerance band, while the internal bore requires an H7 tolerance band. Traditionally, machining such a component involved using a four-jaw chuck on a lathe, necessitating meticulous alignment with dial indicators—a process that is time-consuming, skill-dependent, and prone to inaccuracies. To overcome these limitations, I conceptualized a bespoke tooling fixture that ensures repeatability, reduces setup time, and minimizes operator dependency.

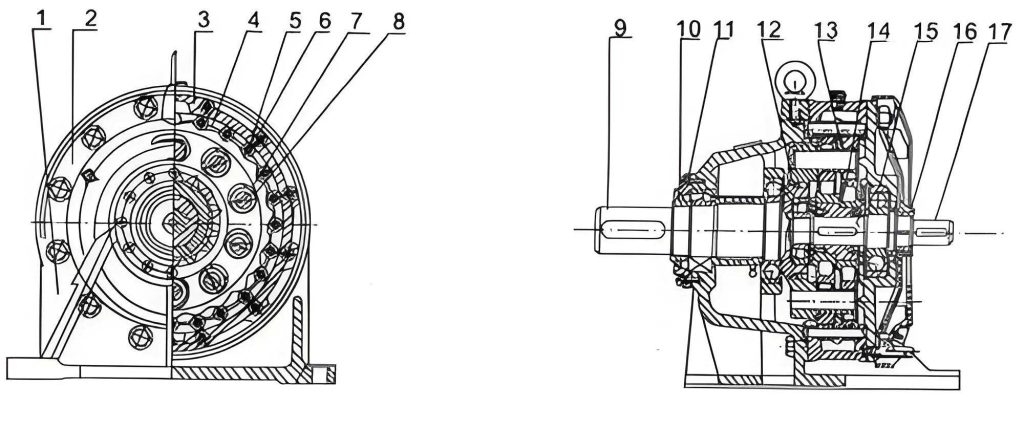

The processing tooling I designed is a monolithic shaft-like device comprising four integral sections arranged sequentially: the taper shank section, the intermediate positioning ring section, the cylindrical shaft section, and the threaded section. Each section serves a distinct functional purpose, as summarized in the table below:

| Section | Primary Function | Key Design Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Taper Shank | Engages with the lathe spindle’s taper socket to ensure coaxial alignment between the tooling and the machine tool axis. | Standard Morse taper (e.g., MT4) matching the lathe; concentricity error < 0.005 mm. |

| Intermediate Positioning Ring | Provides axial (horizontal) reference stop for the workpiece mounted on the tooling. | Width equal to the required shoulder length on the sleeve; perpendicularity within 0.01 mm. |

| Cylindrical Shaft | Fits into the workpiece bore with zero-clearance interference to locate the workpiece radially and align its axis with the tooling axis. | Diameter matching the workpiece bore (e.g., φd H7); features a keyway identical to that on the workpiece. |

| Threaded Section | Accepts a locking nut to clamp the workpiece axially against the positioning ring. | Thread size sufficient to withstand machining forces (e.g., M30x1.5). |

The entire tooling is manufactured with a built-in eccentricity. Specifically, the axis of the cylindrical shaft section (and consequently the threaded section) is offset from the axis of the taper shank by a distance exactly equal to the required unilateral eccentricity (e) of the bearing sleeve. This eccentricity is mathematically defined as:

$$ e = \frac{D_{ext} – d_{int}}{2} + \delta $$

where \( D_{ext} \) is the nominal external bearing seat diameter, \( d_{int} \) is the nominal internal bore diameter, and \( \delta \) is a small correction factor for preload and thermal effects, typically derived empirically. For a 180° double eccentric configuration, the two external surfaces are diametrically opposed. To ensure this, the keyway on the cylindrical shaft is oriented such that its centerline plane is perpendicular to the plane containing the maximum eccentricity vector. This geometric relationship is crucial for the proper functioning of the cycloidal drive, as it ensures the phased oscillation of the cycloidal disc.

When the workpiece—the double partial bearing sleeve—is mounted onto this tooling, its internal bore slides onto the cylindrical shaft, and a key is inserted into the aligned keyways. This key serves dual purposes: it prevents relative rotation between the workpiece and the tooling (angular positioning), and it ensures that the eccentricities of the workpiece are oriented correctly relative to the tooling’s built-in offset. The nut is then tightened on the threaded section, securing the workpiece axially. Since the tooling’s taper shank is seated in the lathe spindle, the entire assembly rotates with its axis defined by the lathe spindle axis. However, due to the eccentricity of the cylindrical shaft, the external surfaces to be machined on the workpiece now revolve around the lathe axis with a fixed offset, enabling them to be turned to the required diameter and tolerance in a single setup. This eliminates the need for individual eccentricity adjustment for each external surface.

The machining process for the double partial bearing sleeve using this tooling involves a systematic sequence of operations. I have broken down the process into distinct steps, incorporating relevant formulas for tolerance calculation and material removal. The table below outlines the steps with key parameters:

| Step | Operation Description | Technical Specifications & Formulas |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Material Preparation | Cut a raw blank from bar stock with sufficient machining allowance. | Initial diameter: \( \phi_{H} = d_{int} + 2 \times \text{allowance}_{radial} \); Length: \( L_3 + \text{allowance}_{axial} \). Allowances typically 2-3 mm per side. |

| 2. Bore Machining | Perform roughing and finishing of the internal bore to achieve H7 tolerance. | Final bore diameter: \( d_{int}^{H7} \). Tolerance range for H7: \( +0 \text{ to } +T_{H7} \), where \( T_{H7} \) is from ISO standards. Surface finish ≤ Ra 1.6 µm. |

| 3. Keyway Cutting | Machine a keyway in the bore using a slotting or broaching process. | Keyway width: \( b \) with tolerance js9; depth per design drawing. |

| 4. Tooling Workpiece Assembly | Mount the workpiece onto the tooling, insert the key, and secure with the nut. | Ensure zero clearance fit; clamping torque for nut: \( T_{clamp} = k \cdot d_{thread} \cdot F_{axial} \), where \( k \) is friction coefficient. |

| 5. Lathe Setup | Insert the tooling’s taper shank into the lathe spindle and support the free end with a dead center. | Spindle speed \( N \) set based on material and tooling; typically \( N = \frac{V_c \times 1000}{\pi \times D_{machining}} \) rpm, where \( V_c \) is cutting speed. |

| 6. First External Diameter Machining | Machine one external bearing seat to k6 tolerance. | Target diameter: \( D_{ext}^{k6} \); Tolerance range for k6: \( + es \text{ to } + ei \), with values from ISO. Length \( L_1 \) as specified. |

| 7. Workpiece Reorientation | Without disassembling, rotate the workpiece 180° on the tooling (using the keyway alignment). | This leverages the 180° opposition of eccentricities. Angular accuracy ensured by keyway perpendicularity. |

| 8. Second External Diameter Machining | Machine the opposite external bearing seat to the same k6 tolerance. | Target diameter: \( D_{ext}^{k6} \); Length \( L_2 \). Maintain same cutting parameters for consistency. |

| 9. Disassembly & Inspection | Remove the workpiece from the tooling and verify dimensions. | Measure eccentricity: \( e_{measured} = \frac{|D_{ext1} – D_{ext2}|}{2} \) should equal design \( e \). Concentricity check via CMM. |

The heart of this method lies in the pre-engineered eccentricity of the tooling, which transforms a complex alignment task into a simple mounting procedure. For a cycloidal drive, the eccentricity value \( e \) is critical as it determines the amplitude of the cycloidal disc’s motion. The theoretical kinematic relationship in a cycloidal drive involves the reduction ratio \( i \), which for a single-stage reducer is given by:

$$ i = \frac{N_p}{N_p – N_c} $$

where \( N_p \) is the number of pins in the ring and \( N_c \) is the number of lobes on the cycloidal disc. The eccentricity \( e \) is related to the gear parameters by:

$$ e = \frac{R_p – R_c}{N_c} $$

Here, \( R_p \) is the pin circle radius and \( R_c \) is the cycloidal disc radius. In practice, for the bearing sleeve, \( e \) is a design input, typically ranging from 1 to 5 mm depending on the size of the cycloidal drive. My tooling is manufactured with this precise eccentricity ground into its cylindrical section. The tolerance on this eccentricity, often within ±0.01 mm, ensures that the resulting sleeve will produce the exact kinematic motion required for efficient operation of the cycloidal drive.

Furthermore, the use of this dedicated tooling has profound implications for production economics and quality control. By eliminating the need for manual indication, setup time is reduced from potentially hours to mere minutes. The repeatability of the process minimizes part-to-part variation, which is crucial for the consistent performance of cycloidal drives in high-duty applications. I have observed that the surface finish and geometric accuracy achieved are superior, often exceeding the specified tolerances. This is attributable to the rigid mounting and elimination of secondary clamping stresses. The tooling also allows for batch production; once the initial setup is verified, multiple sleeves can be machined consecutively with minimal intervention, enhancing throughput significantly.

In terms of material science considerations, the bearing sleeves are typically manufactured from case-hardened alloy steels such as 20CrMnTi or similar grades to withstand the cyclic Hertzian contact stresses from the rolling bearings. The machining parameters must be optimized to avoid introducing residual stresses that could distort the eccentric geometry during heat treatment. For roughing operations, I employ deeper cuts with moderate feeds, while finishing passes use high speeds, low feeds, and sharp cutting tools to achieve the required k6 tolerance. The formula for calculating the theoretical peak-to-valley surface roughness \( R_t \) in turning is:

$$ R_t = \frac{f^2}{8 \cdot R_n} $$

where \( f \) is the feed rate and \( R_n \) is the tool nose radius. By controlling these parameters, I ensure that the surface integrity supports the bearing life within the cycloidal drive assembly.

Another aspect worth detailing is the alignment verification during the tooling’s own manufacture. Before putting it into service, the tooling must be qualified on a precision lathe or grinding machine. The critical dimensions—the taper concentricity, the cylindrical shaft diameter, and most importantly, the eccentricity—are measured using dial test indicators and coordinate measuring machines. The eccentricity verification involves mounting the tooling on a rotary table and measuring the runout of the cylindrical shaft relative to the taper axis. This runout should be exactly twice the designed eccentricity (since the shaft axis is offset). Confirming this ensures that every sleeve produced will have the correct 180° dual eccentricity. This pre-qualification step is fundamental to the success of the entire methodology for producing components for cycloidal drives.

The advantages of this processing tooling are multifaceted and extend beyond mere machining convenience. For maintenance and repair operations in industries reliant on cycloidal drives, such as pulp and paper, mining, or robotics, the ability to quickly and accurately fabricate replacement bearing sleeves on-site can drastically reduce equipment downtime. The tooling design is also adaptable; by manufacturing tooling sets with different eccentricity values, a wide range of cycloidal drive sizes can be accommodated. This modularity makes it a cost-effective solution for job shops and original equipment manufacturers alike. Moreover, the principle can be extended to other components with eccentric features, demonstrating the versatility of the approach.

In conclusion, the development and implementation of this dedicated processing tooling for the 180° double partial bearing sleeve have revolutionized the machining approach for this critical component of cycloidal drives. By integrating the required eccentricity into the tooling itself and using key-based angular positioning, the process becomes straightforward, efficient, and highly accurate. This method significantly lowers the skill barrier for operators, reduces production time, and enhances the consistency and quality of the manufactured sleeves. As cycloidal drives continue to be favored in applications demanding high torque density and shock resistance, reliable manufacturing techniques for their core components become ever more important. The tooling described herein represents a practical and effective solution that aligns with the stringent demands of modern industrial production.