In the context of agricultural robotics, the design and implementation of effective end effectors for fruit harvesting represent a critical challenge, particularly for crops like camellia fruit, which are characterized by their unique growth patterns and sensitivity to damage during picking operations. This article presents a comprehensive account of our work in developing a novel screw-type end effector tailored for the precise and efficient harvesting of camellia fruit. The motivation stems from the limitations of existing harvesting devices, which often suffer from issues such as large size, significant damage to flower buds and branches, and inefficiency in handling the “flower-fruit同期” phenomenon typical of camellia plants. Our approach focuses on creating a lightweight, compact, and adaptable end effector that can be integrated into robotic systems for targeted picking, thereby addressing the need for automation in hilly and mountainous cultivation areas. Through detailed design analysis, force measurements, and extensive testing, we demonstrate the feasibility and performance of this end effector, highlighting its potential to revolutionize camellia fruit harvesting while minimizing collateral damage to the plant.

The camellia fruit, valued for its oil-rich seeds, is predominantly grown in challenging terrains where manual harvesting is labor-intensive and costly. Traditional mechanical harvesters, including vibration-based, combing, and squeezing types, often cause excessive damage to flower buds and young shoots, adversely affecting subsequent yields. This underscores the necessity for precision harvesting solutions. In recent years, soft robotics and flexible end effectors have gained attention due to their compliance and adaptability. However, many existing designs either require complex power sources, are limited to small objects, or are ineffective for fruits with short or no stems. Our research aims to bridge this gap by developing an end effector that mimics the human picking motion—specifically, the twist-and-pull action—while accommodating multiple fruits of varying diameters in a single operation. This article documents the entire process, from conceptual design and force analysis to prototyping and field trials, providing insights into the engineering principles and practical considerations involved in creating a robust harvesting end effector.

The core innovation of our end effector lies in its variable-diameter, multi-fruit picking capability, achieved through a star-topology arrangement of rotating fingers driven by a single motor. This design not only ensures compactness but also enhances reliability by allowing slippage in the transmission system to prevent jamming. In the following sections, we delve into the statistical analysis of fruit dimensions to inform the geometric design, the measurement of separation forces to establish performance benchmarks, and the detailed mechanical design of the end effector components. We then present the results of both laboratory simulations and orchard trials, evaluating metrics such as picking success rate, time per fruit, and bud damage rate. The integration of this end effector with a robotic arm and vision system is also discussed, showcasing its potential for autonomous harvesting. Ultimately, this work contributes to the advancement of agricultural robotics by offering a scalable and efficient solution for camellia fruit picking, with implications for other similar crops.

Before proceeding with the design, we conducted a thorough analysis of camellia fruit characteristics to ensure that the end effector would be effective across the typical size range. A sample of 120 fruits was collected randomly from a camellia orchard, and their maximum radial diameters were measured. The distribution was found to approximate a normal distribution, with the majority of fruits falling within a specific range. This data is crucial for determining the dimensions of the picking zones in the end effector. The results are summarized in Table 1, which illustrates the frequency of different diameter classes. Based on this, we established that the end effector should accommodate fruits with diameters between 25 mm and 45 mm, as this covers over 97% of the sampled population. This statistical foundation guided the spacing between fingers and the conical shape of the fingers, ensuring that the end effector can handle the natural variability in fruit size without requiring complex adjustments.

| Diameter Range (mm) | Number of Fruits | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 20-25 | 1 | 0.83 |

| 25-30 | 12 | 10.00 |

| 30-35 | 34 | 28.33 |

| 35-40 | 45 | 37.50 |

| 40-45 | 26 | 21.67 |

| 45-50 | 2 | 1.67 |

Table 1: Distribution of camellia fruit diameters from a sample of 120 fruits, showing that most fruits (97.5%) fall within the 25-45 mm range.

To design an end effector capable of detaching fruits efficiently, it is essential to understand the forces involved in the picking process. Human pickers typically employ a combination of twisting and pulling actions to minimize the force required and reduce damage. We therefore conducted experiments to measure both the tensile force and torque necessary to separate mature camellia fruits from their branches. A total of 60 fruits were tested—30 for tensile force and 30 for torque—using digital force gauges and torque testers. The fruits were harvested and tested within six hours to maintain consistency. The results, presented in Table 2, reveal that the maximum tensile force recorded was 25.4 N, while the maximum torque was 0.066 N·m. These values serve as critical benchmarks for the end effector design, ensuring that the driving mechanism can generate sufficient force to achieve reliable detachment. The data also highlights the variability in separation forces, which can be attributed to factors such as fruit size, stem thickness, and ripeness.

| Test Type | Maximum Value | Minimum Value | Average Value | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Force (N) | 25.4 | 9.0 | 20.6 | 4.2 |

| Torque (N·m) | 0.066 | 0.015 | 0.037 | 0.012 |

Table 2: Summary of force measurements for camellia fruit separation, indicating the range and average values for tensile force and torque.

Building on this empirical data, we developed a mathematical model to relate the forces exerted by the end effector to the fruit detachment process. When the fingers of the end effector rotate and contact the fruit, they generate frictional forces that apply torque to the fruit stem. Assuming that each finger contacts the fruit with a normal force \( F_N \) and that the friction coefficient between the finger surface and the fruit is \( \mu \), the frictional force \( F_\mu \) can be expressed as:

$$ F_\mu = \mu F_N $$

The torque \( T \) applied by a single finger to the fruit, considering the fruit’s minimum axial diameter \( D_{1min} \), is:

$$ T = F_\mu \cdot \frac{D_{1min}}{2} \times 10^{-3} $$

If \( N \) fingers are in contact with the fruit, the total torque \( T_{total} \) is:

$$ T_{total} = N \cdot T $$

For successful detachment, the total torque must exceed the fruit’s separation torque \( T_d \), as measured in our experiments. Thus, the condition for picking is:

$$ T_{total} \geq T_d $$

Additionally, the normal force \( F_N \) is influenced by the finger’s geometry and the driving mechanism. For a conical finger with an inclination angle \( \theta \), the relationship between the gripping force and the fruit’s weight \( G \) can be approximated by:

$$ G = N F_N \cos \theta $$

However, in our design, the primary action is twisting rather than pulling, so the emphasis is on maximizing torque. These equations guided the selection of the motor and the finger design to ensure that the end effector can generate at least 0.066 N·m of torque under typical conditions.

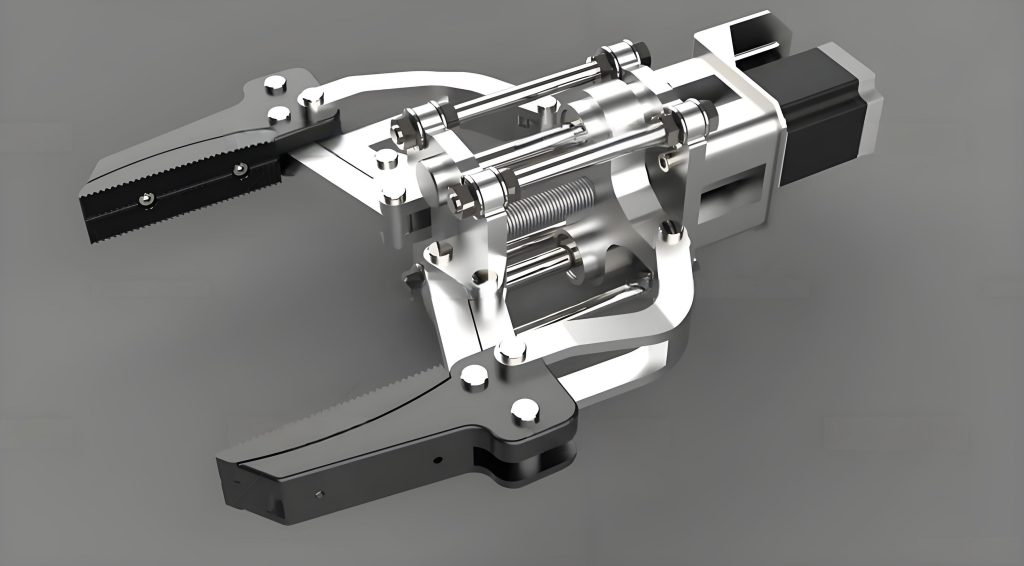

The overall structure of the end effector is designed to be lightweight and compact, with a total mass of 1.2 kg to minimize inertia on the robotic arm. As illustrated in the figure, the end effector consists of several key components: a central driving wheel connected to a geared motor, six driven wheels arranged in a regular hexagonal pattern, and three elastic belts that transmit power from the driver to the driven wheels. Each driven wheel is fixed to a finger, which rotates synchronously. The fingers are conical in shape, made of silicone rubber cast over 3D-printed cores, providing both flexibility and high friction. The base plate and upper support are also 3D-printed, allowing for rapid prototyping and customization. This configuration creates six triangular picking zones around a central finger, enabling the end effector to potentially harvest up to three fruits simultaneously if they are within reach.

The transmission system is a critical aspect of the end effector design. The elastic belts are arranged in an equilateral triangle pattern between the driving wheel and each pair of driven wheels. This topology ensures that power is distributed evenly while allowing for slippage if an obstruction is encountered, thus preventing damage to the motor or fingers. The diameter of the driving wheel and the driven wheels were optimized based on geometric constraints. Given the fruit diameter range of 25-45 mm and the finger dimensions, the distribution diameter \( D \) of the fingers can be calculated using:

$$ D = 2(D_1 + D_2) \cos 30^\circ $$

where \( D_1 \) is the fruit diameter and \( D_2 \) is the finger diameter. With a finger length \( L \) of 50 mm, a small-end diameter of 8 mm, and a large-end diameter of 28 mm, the inclination angle \( \theta \) is determined by:

$$ \tan \theta = \frac{2L}{D_{2max} – D_{2min}} $$

This yields \( \theta \approx 5^\circ \), resulting in a distribution diameter of approximately 92 mm. This geometry ensures that fruits within the target range can be securely engaged by the fingers during rotation.

To enhance the grasping capability, we experimented with three different finger surface designs: smooth conical, threaded conical, and conical with protrusions. Through preliminary tests, the conical design with protrusions was selected due to its higher friction coefficient, which increases the torque transfer to the fruit. The finger manufacturing process involves creating a silicone rubber shell via molding and attaching it to a rigid 3D-printed core. This hybrid approach provides the necessary compliance to adapt to fruit shapes while maintaining structural integrity. The end effector’s control system includes a microcontroller that regulates the motor speed and direction, with feedback from pressure sensors on the fingers to adjust the rotation dynamically. This closed-loop control helps optimize the picking action based on real-time contact forces.

The performance of the end effector was evaluated through a series of tests, beginning with indoor simulations and progressing to field trials in an orchard. For the indoor tests, we constructed a platform consisting of a 6-degree-of-freedom robotic arm, a ZED mini stereo camera for vision, and an NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin for edge computing. The system workflow involves fruit detection and localization using computer vision algorithms, followed by arm movement to position the end effector, and finally activation of the motor for picking. We conducted 60 simulated picking trials using harvested branches with attached fruits, varying the motor speed to assess its impact. The results, summarized in Table 3, show that the average picking success rate across all speeds was 78.33%, with the highest success rate of 80% achieved at 222 and 375 rpm. The picking time per fruit ranged from 3 to 5 seconds, excluding the time for visual localization. Importantly, the bud damage rate remained below 5% in all cases, meeting our objective of minimizing harm to the plant.

| Motor Speed (rpm) | Picking Time (s) | Success Rate (%) | Bud Damage Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 222 | 3-5 | 80 | <5 |

| 375 | 3-5 | 80 | <5 |

| 429 | 3-5 | 75 | <5 |

| Average | 3-5 | 78.33 | <5 |

Table 3: Results of indoor simulated picking trials with the end effector, showing the effect of motor speed on success rate and damage.

Field trials were conducted in a camellia orchard to validate the end effector under real-world conditions. The same motor speeds were tested, with 20 picking attempts per speed, totaling 60 fruits. The environment introduced additional challenges, such as variable fruit orientations, branch flexibility, and obstacles. As shown in Table 4, the average success rate decreased to 65%, with the best performance of 70% at 222 rpm. The picking time remained consistent at 3-5 seconds per fruit, and the bud damage rate stayed below 5%. The decline in success rate compared to indoor tests can be attributed to factors like fruit “yielding” due to branch movement and occasional slippage of fruits from the fingers at higher speeds. These findings indicate that a motor speed of 222 rpm is optimal for this end effector, balancing torque and speed to achieve reliable detachment without excessive force that might cause damage or ejection.

| Motor Speed (rpm) | Picking Time (s) | Success Rate (%) | Bud Damage Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 222 | 3-5 | 70 | <5 |

| 375 | 3-5 | 65 | <5 |

| 429 | 3-5 | 60 | <5 |

| Average | 3-5 | 65 | <5 |

Table 4: Results of orchard field trials with the end effector, demonstrating performance in actual harvesting conditions.

A detailed analysis of the forces during picking reveals insights into the end effector’s operation. When the fingers rotate, they impart a tangential force on the fruit surface, generating torque. The required torque \( T_{req} \) for detachment depends on the fruit-stem bond strength, which varies with fruit size and maturity. From our measurements, the maximum \( T_{req} \) is 0.066 N·m. The torque produced by the end effector \( T_{eff} \) is a function of the motor torque \( T_m \), the transmission ratio, and the friction between fingers and fruit. Assuming an ideal transmission, \( T_{eff} \) can be estimated as:

$$ T_{eff} = \eta \cdot T_m \cdot r $$

where \( \eta \) is the efficiency of the belt transmission and \( r \) is the effective radius ratio. For our motor with a rated torque of 0.1 N·m and an efficiency of approximately 0.85, \( T_{eff} \) exceeds 0.066 N·m, confirming that the design meets the force requirement. However, in practice, losses due to slippage and misalignment can reduce this, which may explain some failures in the field trials. To improve reliability, future iterations could incorporate torque sensors for adaptive control or enhance the finger surface texture to increase friction.

The end effector’s ability to handle multiple fruits simultaneously is a significant advantage over single-fruit pickers. In the hexagonal layout, each pair of adjacent fingers forms a picking zone. When multiple fruits are present within these zones, the rotating action can engage them concurrently. The condition for multi-fruit picking depends on the spatial distribution of fruits. If the fruits are separated by a distance \( d \) and the finger spread is \( D \), then successful picking requires \( d \leq D \). In our design, \( D \) is 92 mm, which accommodates typical fruit clustering patterns. During trials, we observed instances where two fruits were picked in one operation, though this was not systematically quantified. This capability can potentially increase harvesting efficiency, reducing the time per fruit when fruits are densely packed.

Several challenges emerged during the development of this end effector. One issue is the tendency for detached fruits to become trapped between fingers, requiring manual removal or a shaking mechanism. Another is the alignment of the end effector with the fruit; minor misalignments can cause the fingers to miss the fruit or apply uneven force. The vision system plays a crucial role here, but environmental factors like lighting and occlusion can affect accuracy. Additionally, the elastic belts, while providing safety through slippage, require periodic tensioning to maintain performance. These limitations point to areas for future improvement, such as integrating a fruit ejection system, refining the vision algorithms, and using more durable materials for the belts.

From a broader perspective, this end effector represents a step toward autonomous harvesting systems for specialty crops. The integration with a robotic arm and vision system demonstrates a complete workflow from detection to picking. The end effector’s lightweight design minimizes energy consumption and wear on the robot, which is important for prolonged operation. Moreover, the low bud damage rate aligns with sustainable farming practices, preserving future yields. The principles applied here—such as the use of flexible materials, star-topology transmission, and twist-based detachment—could be adapted to other fruits with similar characteristics, such as apples or citrus, with modifications to the finger geometry and force parameters.

In conclusion, we have successfully developed and tested a screw-type end effector for camellia fruit picking that addresses key limitations of existing harvesters. Through statistical analysis of fruit sizes and measurement of separation forces, we established design criteria that informed the mechanical and control systems. The end effector features a compact, lightweight structure with rotating conical fingers driven by a single motor via an elastic belt transmission. Indoor and field trials confirmed that it can achieve an average picking success rate of up to 78.33% in simulations and 70% in orchards, with bud damage rates below 5% and picking times of 3-5 seconds per fruit. While challenges remain, such as fruit trapping and alignment sensitivity, the results validate the feasibility of this approach. Future work will focus on optimizing the finger design for better fruit engagement, enhancing the control system with real-force feedback, and conducting larger-scale trials to assess long-term reliability. This end effector contributes to the advancement of precision agriculture, offering a scalable solution for automating camellia fruit harvesting while protecting the plant’s reproductive capacity.