The development of intelligent agricultural machinery has ushered in a new era where harvesting robots are progressively replacing manual labor. These robots ensure timely fruit harvesting and significantly improve labor productivity. As a critical functional component of a harvesting robot, the end effector performs the direct picking operation. Its design is paramount, directly influencing the success rate and, more importantly, the quality of the harvest, as any mechanical damage to the fruit during detachment reduces its market value and shelf life.

Traditional harvesting methods employed by robotic end effectors often rely on mechanical twisting or scissor-like cutting. While these methods are functionally effective, they typically require the end effector to grasp the fruit firmly. This firm grip, necessary to apply the twisting or cutting force to the stem, frequently leads to bruising, puncturing, or other forms of mechanical damage to the delicate fruit skin and flesh. This limitation has driven the search for more delicate, non-damaging harvesting principles. Observing nature often provides elegant solutions to complex engineering problems. In this context, the feeding mechanism of snakes offers a remarkable model. A snake’s jaw possesses a unique structure and kinematic sequence—alignment, extension, jaw opening, and a powerful occlusal bite—that allows it to capture and restrain prey efficiently. This biological process shares a fundamental similarity with the desired robotic harvesting sequence: approach, engage, detach, and collect. Inspired by this biomimetic principle, I have designed a novel robotic end effector that mimics the occlusal bite of a snake’s jaw. This design aims to separate the fruit from its stem without applying crushing forces to the fruit itself. The core operation involves using an adsorption mechanism to gently hold the fruit, an occlusal mechanism to cleanly cut the stem, and a flexible conveying system to transport the harvested fruit without impact.

The core harvesting cycle of this bionic end effector can be mapped directly to the biological analogue, as summarized in the table below.

| Action Phase | Biological Analogue (Snake) | Robotic System Component | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment | Head/Neck Movement | Robot Arm + Vision System | Position the end effector relative to the target fruit. |

| Extension | Body Forward Motion | Robot Arm Trajectory | Bring the end effector into the immediate vicinity of the fruit. |

| Jaw Opening & Engagement | Mandible Depression | Adsorption Mechanism Extension | Gently attach to the fruit using vacuum, pulling the stem taut. |

| Occlusal Bite | Mandible Adduction | Occlusal Mechanism Actuation | Cut the stem via a scissoring action without gripping the fruit. |

| Collection | Swallowing/Manipulation | Flexible Conveyance System | Guide the detached fruit softly into a collection bin. |

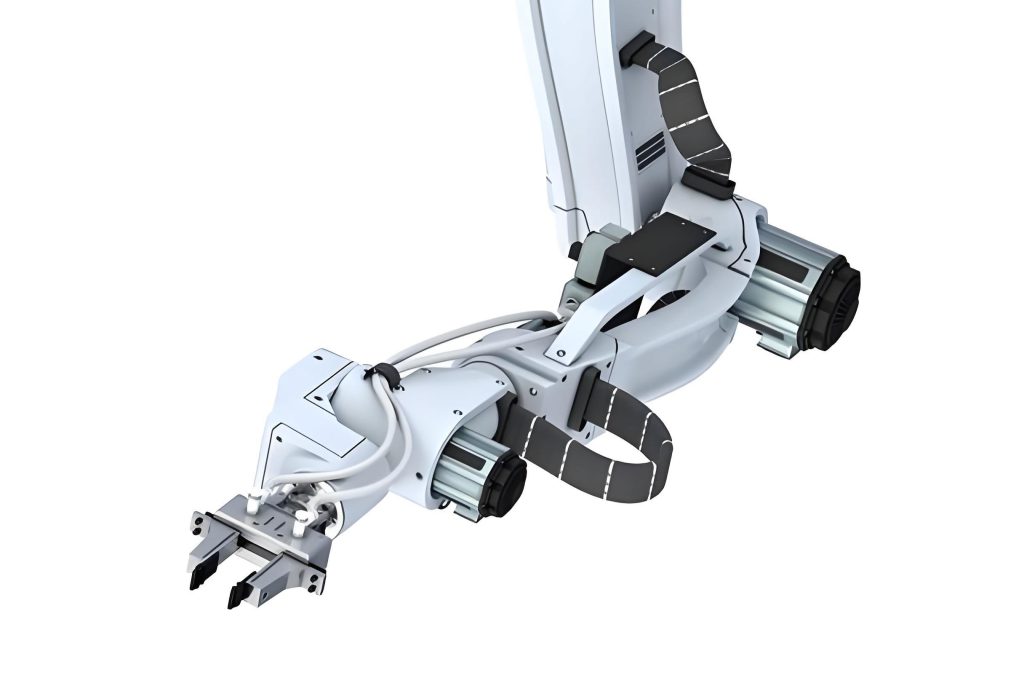

The three-dimensional mechanical structure was conceived and assembled within SolidWorks. The overall design integrates several key subsystems that work in a precise sequence. The primary components are the Adsorption Unit, the Occlusal Mechanism, the Stem-Cutting Assembly, and the Fruit Conveyance System. The operational sequence is as follows: First, the occlusal jaws open, and the adsorption unit extends to make contact and adhere to the target fruit using vacuum pressure. Second, the adsorption unit retracts, drawing the fruit into the central harvesting envelope and, crucially, pulling the stem straight to present it optimally to the cutters. Third, the occlusal mechanism is actuated, driving the cutting blades together to cleanly sever the stem. Finally, the vacuum is released, allowing the fruit to drop onto a flexible chute that guides it gently into a collection container, completing a non-damaging harvest cycle.

The Adsorption Unit is responsible for the initial gentle contact and restraint. It utilizes a venturi-type vacuum generator coupled with a soft, porous sponge suction cup. This combination creates a secure hold on fruit with irregular surfaces without applying concentrated pressure. The unit is mounted on a linear guide and actuated by a pneumatic cylinder, allowing it to extend towards the fruit and retract to pull the stem taut.

The heart of the innovation lies in the Occlusal Mechanism. Its design is based on a multi-linkage transmission system that exploits the parallel motion property of a parallelogram configuration. A central pneumatic cylinder acts as the prime mover. The cylinder’s rod is connected to an H-shaped link, which, through a set of connecting rods, drives a parallelogram linkage group. Replaceable cutting blades are attached to the apex of trapezoidal connectors on this linkage. The kinematics are straightforward: cylinder extension causes the parallelogram links to rotate outward about their pivots, separating the blades (simulating jaw opening). Cylinder retraction causes the links to rotate inward, bringing the blades together in a shearing motion (simulating the occlusal bite). The motion profile can be defined. If we denote the cylinder displacement as $d_c(t)$, the resulting horizontal displacement $x_b(t)$ of a blade can be modeled through the linkage geometry. For a simplified model with near-linear transmission in the operating range, we can approximate:

$$x_b(t) \approx k \cdot d_c(t)$$

where $k$ is a kinematic gain factor determined by the link lengths, typically $k > 1$ to achieve amplified blade motion from the cylinder stroke.

The Stem-Cutting Assembly is integrated directly with the occlusal mechanism’s jaws. To ensure a clean cut and prevent the stem from slipping, the blades are arranged in an overlapping, scissor-like fashion with a precise gap (e.g., 0.5 mm). Furthermore, one jaw features a serrated guiding channel above its blade. During closure, this channel works with the opposing blade to trap and correctly position the stem within the cutting gap, ensuring reliable severance even if the stem is not perfectly centered initially. The cutting force $F_c$ required must overcome the shear strength of the stem material. The force provided by the pneumatic cylinder $F_{cyl}$ is transmitted and amplified by the linkage mechanism to produce the cutting force at the blade. A static force analysis yields:

$$F_c = \eta \cdot \frac{L_1}{L_2} \cdot F_{cyl}$$

Here, $\eta$ represents the mechanical efficiency of the linkage, and $L_1$ and $L_2$ are characteristic lengths of the driving and driven links, respectively. The pneumatic system must be sized to provide sufficient $F_{cyl}$ to meet the required $F_c$ for target stems.

The Fruit Conveyance System is designed for post-detachment damage prevention. It consists of a collection funnel attached via a T-connector to the main body and linked through an L-shaped rod to the moving parallelogram. This clever attachment allows the funnel’s orientation to adapt slightly to the motion of the jaws. The funnel leads to a flexible, expandable nylon cloth hose that guides the fruit softly into a collection box, minimizing impact forces during the drop.

To validate the kinematic design and ensure the absence of interference, a dynamic simulation was performed. The SolidWorks model was exported and analyzed in ADAMS software. A translational motion drive was applied to the main cylinder joint, simulating its extension and retraction over a 5-second cycle. The simulation confirmed the coordinated motion: as the adsorption unit retracted (simulating fruit pull-in), the occlusal jaws closed. The plots for blade displacement and velocity were extracted. The maximum horizontal blade displacement was approximately 80 mm per side, giving the end effector an effective harvesting envelope for fruits with a diameter up to 160 mm. The velocity profiles were smooth without sharp discontinuities, indicating well-balanced dynamics and the absence of sudden impact loads within the mechanism, which is essential for smooth operation and reduced vibration. The smooth velocity $v_b(t)$ is the derivative of the displacement $x_b(t)$:

$$v_b(t) = \frac{dx_b(t)}{dt} \approx k \cdot \frac{dd_c(t)}{dt}$$

The absence of spikes in $v_b(t)$ confirms the lack of kinematic singularities or harsh impacts in the designed motion path.

| Simulation Metric | Result | Design Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Max Single-Blade Displacement ($x_{b_{max}}$) | ~80 mm | Defines max fruit diameter (~160 mm). |

| Blade Velocity Profile ($v_b(t)$) | Smooth, continuous | Indicates good dynamic performance, low vibration. |

| Coordination between Adsorption & Occlusion | Proper phasing verified | Validates the sequence for successful stem cutting. |

The control system for this end effector employs a distributed architecture, separating high-level decision-making from low-level real-time actuation. This enhances reliability and modularity. The hardware structure revolves around two decentralized pneumatic subsystems managed by a central microcontroller.

The system hardware is built around a master-slave configuration. A host computer (the master) runs the main human-machine interface and vision processing algorithms. It sends high-level commands (e.g., “harvest now”) via a serial communication protocol to a dedicated microcontroller (the slave). This microcontroller, acting as the real-time controller, interfaces directly with the power electronics. It controls relays which switch the power to the solenoids of various pneumatic valves. These valves, in turn, control the actuators: a 3/2-way solenoid valve activates the vacuum generator for adsorption, and 5/2-way solenoid valves control the double-acting cylinders for the adsorption unit’s linear motion and the occlusal mechanism’s bite action. Flow control valves (needle valves) are installed in each actuator’s air lines to allow precise adjustment of extension/retraction speeds, enabling tuning of the end effector‘s aggressiveness and cycle time. The pneumatic circuit was designed and validated using FluidSIM software prior to physical implementation.

The software philosophy emphasizes modularity for clarity, maintainability, and future expansion. The main program executes a sequential state machine that calls specific, self-contained subroutines. The key software modules include:

1. Object Recognition Subroutine: Processes image data to locate the target fruit and estimate its pose.

2. Robotic Arm Planner Subroutine: Calculates a collision-free trajectory for the manipulator to position the end effector accurately.

3. Adsorption Control Subroutine: Manages the timing of vacuum generation and release.

4. Harvesting Control Subroutine: Sequences the cylinder extensions/retractions for the occlusal bite cycle.

A typical control sequence for the harvesting action involves a timed sequence of outputs from the microcontroller. Let $u_{vac}(t)$, $u_{ads}(t)$, and $u_{occ}(t)$ represent the control signals (ON/OFF) for the vacuum generator, adsorption cylinder, and occlusion cylinder solenoids, respectively. A successful harvest cycle $T_{cycle}$ can be defined by a time-sequence like:

$$

\begin{aligned}

&0 < t \leq t_1: & u_{occ}(t)=ON_{extend} &\quad (\text{Jaws open}) \\

&t_1 < t \leq t_2: & u_{ads}(t)=ON_{extend} &\quad (\text{Adsorber extends}) \\

&t_2 < t \leq t_3: & \text{Vacuum Stabilization Delay} & \\

&t_3 < t \leq t_4: & u_{ads}(t)=ON_{retract} &\quad (\text{Adsorber retracts, pulls fruit}) \\

&t_4 < t \leq t_5: & u_{occ}(t)=ON_{retract} &\quad (\text{Jaws close, cut stem}) \\

&t_5 < t \leq t_6: & u_{vac}(t)=OFF &\quad (\text{Release vacuum}) \\

&t_6 < t \leq T_{cycle}: & u_{occ}(t)=ON_{extend} &\quad (\text{Reset jaws open})

\end{aligned}

$$

The timing parameters $t_1$ through $t_6$ are determined empirically and tuned for specific fruit and stem characteristics.

The performance of the end effector can be modeled and evaluated from several perspectives. Beyond the basic kinematics and statics, dynamic considerations are important. The moving parts have mass, and the pneumatic actuation provides a force that accelerates them. A simple dynamic model for the occlusal jaw linkage, considering it as a rotating inertia $J$ driven by a torque $\tau$ derived from the cylinder force, can be expressed as:

$$J \frac{d^2\theta}{dt^2} + b \frac{d\theta}{dt} = \tau(t)$$

where $\theta$ is the angular position of the primary link, $b$ is a viscous damping coefficient, and $\tau(t)$ is related to the cylinder force $F_{cyl}(t)$ and the instantaneous linkage geometry. This model helps in simulating the transient response and selecting appropriate cylinder sizes and supply pressures to achieve the desired closing speed without excessive impact. Furthermore, the vacuum adhesion force $F_{vac}$ must be sufficient to hold the fruit against inertia and any reaction forces during stem cutting. It can be estimated as:

$$F_{vac} = A_{eff} \cdot \Delta P$$

where $A_{eff}$ is the effective area of the suction cup seal and $\Delta P$ is the pressure differential. This force must satisfy the safety condition:

$$F_{vac} > m_f \cdot a_{max} + F_{reaction}$$

with $m_f$ being the fruit mass, $a_{max}$ the maximum acceleration during retraction, and $F_{reaction}$ a marginal force from stem tension during cutting.

The choice of a pneumatic system offers advantages like high power-to-weight ratio and simplicity but introduces control nuances related to air compressibility. The relationship between the control valve command and the cylinder force is not instantaneous. A first-order approximation for the pressure build-up in a cylinder chamber can be used for control design:

$$\tau_p \frac{dP}{dt} + P = K_u \cdot u(t)$$

where $P$ is the chamber pressure, $\tau_p$ is a time constant depending on volume and orifice flow, $K_u$ is a gain, and $u(t)$ is the valve command signal. Understanding this helps in designing the timing logic in the microcontroller to ensure precise sequencing.

In practical application, the end effector must be integrated with a vision system and a manipulator. The overall harvesting loop forms a cyber-physical system. The performance metric is not just the success rate of a single detachment, but the cycle time and robustness in a cluttered, natural environment. The end effector design must therefore be robust to minor positional errors from the vision/arm system. The combination of the compliant suction cup and the guiding serrations on the cutter provides this robustness by accommodating slight misalignments. For future development, sensor feedback could be integrated directly into the end effector. A miniature force sensor could verify successful adsorption, and a proximity sensor could confirm fruit presence in the collection funnel, closing the perception-action loop at the end effector level and making the system more autonomous and reliable.

| Design Aspect | Key Feature | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Harvesting Principle | Bionic Occlusal Bite | Eliminates crushing grip on fruit, minimizing damage. |

| Fruit Restraint | Vacuum Adsorption | Provides secure, distributed hold on delicate surfaces. |

| Stem Cutting | Guided Scissor Action | Ensures clean, reliable severance of the stem. |

| Fruit Handling | Flexible Conveyance Chute | Prevents impact damage post-detachment. |

| Actuation & Control | Decentralized Pneumatic System | Offers high force, simplicity, and modular control. |

In conclusion, the design and development of this bionic occlusal end effector present a significant step towards gentle robotic fruit harvesting. By drawing inspiration from the natural mechanics of a snake’s bite, the design successfully decouples the fruit holding function from the stem cutting function. The adsorption mechanism provides a damage-free grip, the multi-link occlusal mechanism delivers a powerful and precise cutting action, and the flexible conveyance system ensures gentle handling after detachment. The distributed control architecture, with its modular software and pneumatic hardware, provides a reliable and tunable platform for executing the complex harvesting sequence. Simulation validates the kinematic soundness and dynamic smoothness of the mechanism. While challenges remain in perfecting the integration with vision systems and handling highly variable field conditions, this end effector core technology offers a promising, biologically-inspired solution to the critical problem of mechanical fruit damage during automated harvesting, potentially increasing the viability and economic benefit of harvesting robots for high-value crops.