In the realm of underwater robotics, the end effector serves as the crucial interface between the robotic system and its environment, directly determining the efficacy of tasks such as sampling, manipulation, and intervention. As researchers dedicated to advancing underwater technologies, we have identified a persistent challenge: commercial end effectors often fail to simultaneously meet the demands of high load capacity and high adaptability, struggling to balance the dual requirements of non-destructive grasping and firm holding in dynamic, unpredictable underwater settings. This limitation is particularly acute in applications like deep-sea exploration, archaeological recovery, and biological sampling, where the end effector must handle a wide variety of objects, from fragile corals to robust tools. Our work addresses this gap by introducing a novel biomimetic soft-rigid hybrid end effector, inspired by the ingenious claw structure of lobsters. This end effector, which we call the LobSTER Gripper, embodies a design philosophy that merges passive compliance with rigid support, enabling phased stiffness adaptation without complex control systems. Through this approach, we aim to provide a low-cost, reliable, and easily transferable solution for adaptive underwater grasping, enhancing the capabilities of underwater unmanned systems.

The performance of an underwater end effector is paramount, as it directly influences mission success rates. Traditional rigid end effectors, while strong, often lack the flexibility to safely interact with delicate or irregularly shaped objects. Conversely, soft end effectors offer excellent conformity but suffer from limited load-bearing capacity. This dichotomy has driven the development of hybrid systems, yet many existing designs rely on intricate actuation mechanisms that increase cost, control complexity, and potential failure points, especially in high-pressure underwater environments. Our research seeks to overcome these hurdles by leveraging biological principles to create an end effector that is both adaptive and robust. The lobster’s claw, with its combination of a hard exoskeleton and underlying soft tissue, provides a natural blueprint for a gripper that can initially conform gently to an object and then apply substantial force. By reversing this structure—placing a soft finger over a rigid core—we achieve a “soft touch, rigid grip” mechanism that passively adapts to object geometry before securing a firm hold. This paper details the design, modeling, experimental validation, and potential applications of this innovative end effector, emphasizing its role in advancing underwater manipulation technology.

| End Effector Type | Primary Materials | Actuation Method | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Load Capacity | Adaptability to Irregular Shapes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid End Effector | Aluminum, Titanium, Stainless Steel, Engineering Plastics | Electric Motors, Hydraulic Cylinders | High structural strength, Excellent load-bearing, Durability in harsh conditions | Low compliance, Risk of damaging delicate objects, Poor performance with pose uncertainties | Often >10 kg | Low (requires precise alignment) |

| Soft End Effector | Silicone Elastomers, Rubber, Polyurethane | Pneumatic (Air/Water), Hydraulic, Tendon-driven | High passive adaptability, Safe for fragile items, Conformity to complex geometries | Low load capacity, Material degradation under pressure, Potential for instability | Typically <5 kg | Very High (passive enveloping) |

| Soft-Rigid Hybrid End Effector | Combinations (e.g., Soft polymer over rigid skeleton) | Various (Motor, Pneumatic, Passive) | Balanced load and adaptability, Tunable stiffness, Potential for damage-free and strong grasping | Design complexity, Integration challenges, Control may be needed for active hybrids | Medium to High (5-20 kg) | High (via combined mechanisms) |

The evolution of underwater end effectors reflects the growing demand for versatile tools in ocean engineering and science. Initially, end effectors were designed for heavy-duty tasks like pipeline manipulation, prioritizing strength over finesse. However, as missions expanded to include delicate operations, the need for adaptive end effectors became clear. Soft robotics offered a pathway, with fluidic actuators enabling gentle grasping. Yet, the fundamental trade-off between softness and strength remained. Our design philosophy centers on a passively adaptive end effector that requires no additional control for its initial conforming phase. This is achieved through a biomimetic architecture where the soft external layer provides the initial “soft touch,” and the internal rigid structure ensures the subsequent “rigid grip.” This two-phase operation is central to the end effector’s functionality, allowing it to handle diverse objects without switching mechanisms or complex algorithms.

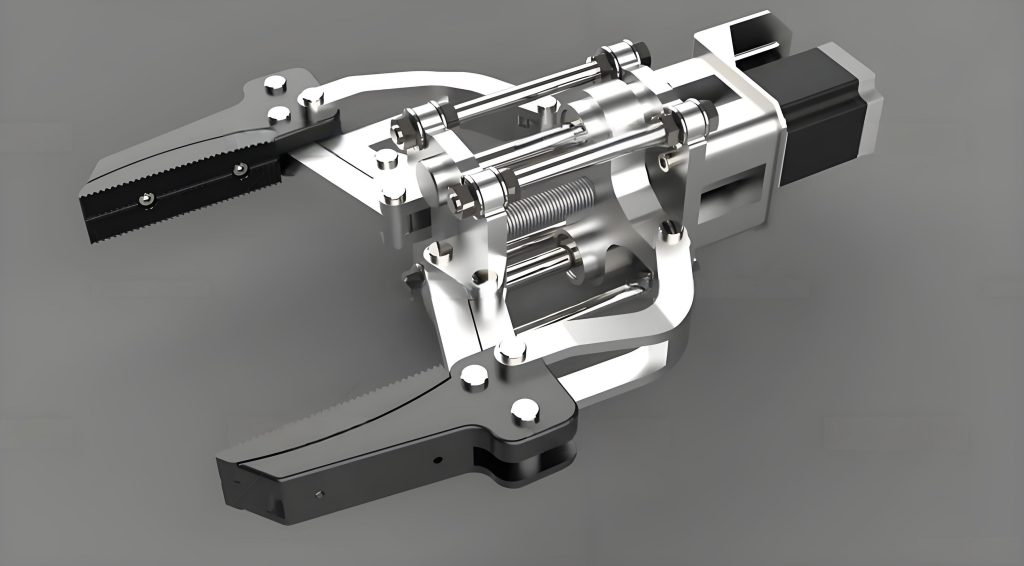

The core innovation of our end effector lies in its biomimetic reversed structure. In nature, a lobster’s claw features a hard exterior powered by soft muscles. For our end effector, we invert this: a soft, compliant finger sheathes an internal rigid finger. This reversal serves a protective purpose, allowing the soft material to make first contact, distribute pressure, and conform to the object’s surface, thereby minimizing the risk of damage. The rigid finger then engages, providing a stable, high-force grip. This design mimics the functional morphology of the lobster claw but re-purposes it for nondestructive grasping. The soft finger is fabricated from a polyurethane elastomer (e.g., Shore A90 hardness) via vacuum casting, offering hyperelastic behavior that enables large, reversible deformations. The rigid finger and base are 3D-printed from resin or can be machined from metal for higher loads, ensuring the end effector can be tailored to specific mission requirements. The surfaces of both fingers are textured with biomimetic齿纹 patterns inspired by the lobster claw to enhance friction underwater, a critical factor for reliable grasping in aqueous environments.

From a mechanical perspective, the grasping process of this hybrid end effector can be modeled in two distinct phases. In the initial “soft touch” phase, only the soft exterior is in contact. The contact force generated by the soft finger, \( F_{\text{soft}} \), is a nonlinear function of its deformation \( \delta \), governed by its hyperelastic material properties. This can be approximated by a polynomial relation:

$$ F_{\text{soft}} = k_1 \delta + k_2 \delta^2 $$

where \( k_1 \) and \( k_2 \) are coefficients derived from the material’s constitutive model. This phase is characterized by a gradual increase in force as the soft finger envelops the object, maximizing contact area and initial stability. The end effector’s adaptability here is entirely passive, requiring no sensory feedback or control adjustment, which simplifies the overall system architecture. As the gripper continues to close, the internal rigid finger makes contact, marking the beginning of the “rigid grip” phase. The total grasping force \( F_{\text{total}} \) now becomes the sum of the soft finger’s contribution and the rigid finger’s reaction force:

$$ F_{\text{total}} = F_{\text{soft}}(\delta) + F_{\text{rigid}} $$

Here, \( F_{\text{rigid}} \) represents the force provided by the rigid skeletal structure, which is significantly stiffer. This phase exhibits a sharp increase in system stiffness, enabling the end effector to apply substantial holding forces suitable for heavy or slippery objects. This phased transition is the key to the end effector’s dual capability, allowing it to function as both a compliant gripper for delicate items and a powerful clamp for robust objects. The end effector’s performance is thus defined by this hybrid force-displacement profile, which we have experimentally validated.

To quantitatively assess the effectiveness of our biomimetic end effector, we conducted a series of grasping success experiments under controlled conditions. The experimental setup involved mounting the end effector on a robotic arm positioned above a water tank. A test object (a seashell) was placed at a marked standard position on the tank bottom. For each trial, before descending to grasp, the end effector’s approach pose was subjected to random perturbations in the horizontal plane (Δx, Δy) and rotation (θ), simulating disturbances caused by underwater currents. The gripper would then close, attempt to lift the object out of the water, and the success or failure was recorded. We compared our LobSTER Gripper against a conventional rigid end effector of similar size. Over 100 trials each, our soft-rigid hybrid end effector achieved a remarkable 100% success rate, significantly outperforming the rigid end effector, which succeeded only 80% of the time. This stark difference underscores the advantage of the passive adaptive phase in compensating for pose uncertainties—a common challenge in underwater operations where precise positioning is difficult. The end effector’s ability to conform initially ensures that even with misalignment, contact is made and stabilized before the rigid grip engages, preventing the object from being pushed away.

| End Effector Type | Number of Trials | Successful Grasps | Success Rate | Primary Failure Mode Observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomimetic Soft-Rigid End Effector (LobSTER Gripper) | 100 | 100 | 100% | None |

| Traditional Rigid End Effector | 100 | 80 | 80% | Object slippage or push-away during initial contact |

The integration of sensing capabilities is a vital direction for enhancing the intelligence and autonomy of underwater end effectors. The often murky, dark, and dynamic underwater environment severely limits the reliability of vision systems, making tactile perception a crucial supplement. For our end effector, future iterations will incorporate visuo-tactile sensors at the base of the fingers. These sensors, based on camera observation of deformations in a soft, textured membrane, can provide rich data about contact geometry, force distribution, and slip detection. This tactile feedback can be used to modulate grasping force in real-time, enabling the end effector to handle extremely fragile objects by preventing excessive pressure. The development of such perceptive end effectors represents a significant step toward fully autonomous underwater manipulation, where the robot can sense, decide, and adapt its grip based on tactile cues. Current tactile technologies for underwater use include capacitive, resistive, piezoelectric, optical (e.g., fiber Bragg gratings), and visuo-tactile sensors. Each has its trade-offs in terms of sensitivity, pressure resistance, and integration complexity. For our end effector design, visuo-tactile sensing is particularly attractive due to its high spatial resolution and relatively low cost, though challenges like waterproofing and pressure compensation must be addressed.

Despite its promising performance, our current end effector prototype has limitations that guide future research. First, the transition from the soft touch to the rigid grip phase, while effective, can sometimes exhibit a noticeable force discontinuity if the rigid finger contacts the object at a single point rather than along a surface. This point loading could potentially stress small contact areas on delicate objects. Optimizing the geometry and relative spacing of the soft and rigid fingers can help create a more gradual stiffness transition. Second, the current validation was performed in static water; the end effector’s performance under dynamic flows or at significant depths with high hydrostatic pressure remains to be tested. Pressure can affect the material properties of the soft polymer and the behavior of any integrated sensors. Third, while the end effector is passive and easy to integrate, its grasping force profile is fixed by its mechanical design. Future work could explore tunable stiffness mechanisms, such as granular jamming or low-melting-point alloy inserts within the soft layer, to allow active adjustment of the soft finger’s rigidity for different object classes, all while maintaining the end effector’s core simplicity.

The broader implications of this work are substantial for the field of underwater robotics. By providing a mechanically intelligent, passively adaptive end effector, we lower the barrier to entry for high-performance underwater manipulation. This end effector can be modularly attached to existing commercial remotely operated vehicle (ROV) manipulator arms, instantly upgrading their capability to handle delicate and diverse objects without requiring changes to the vehicle’s control software or power systems. This plug-and-play adaptability is a key engineering advantage. Furthermore, the biomimetic principle demonstrated here—using a soft exterior for initial compliance and a rigid interior for ultimate strength—can be extended to other robotic end effectors beyond underwater applications, such as in space, medical, or logistics robotics where adaptive, reliable grasping is needed.

In conclusion, our research presents a novel biomimetic soft-rigid hybrid end effector that effectively addresses the longstanding challenge of combining adaptive, damage-free grasping with strong, reliable holding in underwater environments. Inspired by the lobster claw, the end effector employs a reversed structure of a soft finger over a rigid core to achieve a two-phase “soft touch, rigid grip” mechanism. Experimental results confirm its superior grasping success rate under pose disturbances compared to traditional rigid end effectors. This design offers a practical, low-complexity, and cost-effective solution for enhancing the versatility of underwater robotic systems. Future work will focus on integrating tactile sensing for closed-loop control, optimizing the stiffness transition profile, and testing the end effector in more realistic oceanic conditions. The development of such intelligent, adaptive end effectors is crucial for unlocking the full potential of underwater robots in exploration, science, and industry, making them more capable partners in uncovering the mysteries of the deep sea.

The mathematical modeling of the end effector’s behavior can be further refined to include hydrodynamic effects. When operating underwater, the interaction between the moving fingers and the fluid medium generates drag forces and added mass effects, which can influence the grasping dynamics. A more comprehensive model for the force during closure might incorporate a hydrodynamic damping term. For instance, during the soft finger deformation, the effective force balance could be extended to:

$$ F_{\text{applied}} = F_{\text{soft}}(\delta) + F_{\text{rigid}} + F_{\text{damp}} $$

where \( F_{\text{damp}} = c \dot{\delta} \), with \( c \) being a damping coefficient related to the finger’s geometry and the fluid’s viscosity. This becomes particularly relevant for high-speed grasping or in the presence of currents. Understanding these dynamics is essential for predicting the end effector’s performance in varied flow conditions and for designing control strategies that compensate for fluid forces, ensuring consistent operation regardless of environmental disturbances.

| Sensor Type | Working Principle | Key Advantages for Underwater Use | Key Challenges for Underwater Use | Integration Potential with Soft-Rigid End Effector |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitive | Measures change in capacitance due to contact deformation | High sensitivity, Good spatial resolution | Sensitive to water/contaminants, Sealing challenges at depth | Moderate (requires waterproof encapsulation) |

| Resistive | Measures change in resistance due to strain or pressure | Robust, Simple circuitry, Can be made pressure-tolerant | Lower sensitivity, Can drift with temperature/humidity | High (can be embedded in soft material) |

| Piezoelectric | Generates charge in response to dynamic stress | Excellent for dynamic force/vibration detection, Low drift | Poor for static force measurement, Signal conditioning needed | Moderate (for impact/slip detection) |

| Optical (Fiber Bragg Grating) | Measures wavelength shift in reflected light from fiber under strain | Immune to electromagnetic interference, High pressure tolerance, Multiplexing capability | High cost, Lower spatial resolution, Complex interrogation unit | Moderate (fibers can be embedded along fingers) |

| Visuo-Tactile | Uses camera to capture deformation of a soft, patterned skin | Very high spatial resolution, Rich data (shape, force distribution), Lower unit cost | Requires clear optical path, Housing must withstand pressure, Potential for biofouling | High (ideal for base of soft finger as done in our planned work) |

The design and testing of this end effector also highlight the importance of material selection for underwater applications. The soft finger material must not only exhibit hyperelasticity for large deformations but also resist swelling, plasticization, and degradation when immersed in seawater for extended periods. Polyurethane elastomers like the one used (Hei-cast 8400) offer a good balance, but long-term aging tests are necessary. Similarly, the rigid components must resist corrosion; using polymers like PEEK or metals like titanium could be explored for deeper deployments. The modular nature of our end effector design facilitates such material swaps, allowing it to be customized for different operational depths and durations, enhancing its versatility as a universal end effector platform.

Another avenue for enhancing this end effector is through the implementation of learning-based control. With integrated tactile sensors, the end effector can collect data during grasping attempts. This data can train machine learning models to predict grasp stability, estimate object properties like hardness or slipperiness, and even classify objects. For example, a neural network could learn to map the visuo-tactile image patterns from the initial soft contact phase to the minimum required rigid grip force, optimizing energy use and minimizing damage risk. This would transform the end effector from a passively adaptive tool into an intelligently adaptive one, capable of learning from experience and improving its performance over time—a significant leap forward for autonomous underwater intervention.

The principle of phased stiffness adaptation embodied in our end effector has parallels in other biological systems beyond lobsters. For instance, the human hand uses soft fingertips for sensitive exploration and the rigid bones and tendons for powerful gripping. This biomimetic insight reinforces the universality of the hybrid approach for manipulation. In engineering terms, the end effector’s performance can be characterized by metrics such as the adaptability index (the range of object sizes and shapes it can grasp successfully) and the force transmission efficiency (the ratio of output gripping force to input actuator force). Our preliminary analysis suggests that the soft layer improves the adaptability index significantly, while the rigid core maintains high force transmission, especially once engaged. Quantitative models linking design parameters (soft layer thickness, modulus, rigid finger geometry) to these performance metrics are an area for future detailed study, enabling optimized designs for specific task specifications.

In summary, the development of adaptive end effectors like the LobSTER Gripper is a critical step toward more capable and autonomous underwater robotic systems. By solving the fundamental trade-off between gentleness and strength through a clever, biomimetic, passive mechanism, this end effector offers a practical and effective tool for a wide range of underwater applications. As we continue to refine the design, integrate sensing, and test in harsher environments, we move closer to realizing the vision of robots that can interact with the underwater world as deftly and reliably as human divers, but with far greater endurance and reach. The end effector, as the terminal point of action, truly holds the key to unlocking the full potential of underwater robots for science, industry, and exploration.