In the advancement of agricultural modernization, robotic technology has become increasingly prevalent in various farming operations. Among these, orchard picking stands out as a critical application scenario for agricultural robots, attracting significant attention from both academia and industry. However, hilly orchard environments present complex and variable conditions that pose substantial challenges to robotic systems, particularly the end effector. As a researcher focused on agricultural robotics, I have dedicated efforts to addressing these challenges through innovative design. In this article, I propose a lightweight vision-force control coupled end effector tailored for hilly orchard picking robots. This design integrates advanced sensing and actuation mechanisms to achieve high-precision fruit recognition and harvesting in rugged terrains. The end effector is engineered to be lightweight, sensitive, and responsive, ensuring efficient performance in demanding conditions. Through theoretical modeling and optimization, I have refined key parameters such as the robotic arm structure, actuator dimensions, and sensor configurations. The goal is to provide a robust solution that enhances the autonomy and reliability of picking robots, thereby supporting intelligent orchard management. This work stems from the need to overcome limitations in traditional end effectors, which often struggle with the uneven terrain, visual obstructions, and delicate fruit handling requirements of hilly orchards. By coupling visual perception with force control, my end effector aims to deliver adaptive and precise operations, paving the way for broader adoption of robotics in agriculture.

The challenges in hilly orchard picking are multifaceted, impacting every aspect of robotic design. Firstly, the uneven topography of hilly regions significantly affects localization and motion control. The undulating landscapes and dense vegetation can interfere with GPS signals, leading to reduced positioning accuracy. This makes it difficult for the robot to determine its exact location, which is crucial for navigation and task execution. Moreover, steep slopes and irregular ground surfaces demand robust climbing and obstacle-crossing capabilities from the robot. The end effector must operate reliably despite these motion uncertainties, requiring stable control algorithms. For instance, rocks and soil pits can cause chassis scraping or tipping, disrupting operations and compromising safety. To mitigate this, the end effector should be designed with lightweight materials to reduce inertial loads and enhance maneuverability. In my approach, I consider these factors during the optimization of the end effector’s dynamics, ensuring it can function effectively even when the base robot experiences disturbances. The end effector’s responsiveness is key to maintaining picking accuracy in such environments.

Secondly, visual recognition is severely hampered by canopy occlusion in hilly orchards. The dense foliage and overlapping branches create a complex visual environment where fruits are often partially or fully hidden. This leads to missed detections and inefficient picking. Additionally, sunlight filtering through leaves creates stark contrasts and shadows, while background elements like tree bark and weeds introduce noise into image processing. These variations in lighting and occlusion result in inconsistent fruit features, making it challenging to derive reliable data for subsequent grasping actions. To address this, my end effector incorporates a sophisticated visual recognition module. This module utilizes stereo vision with high-resolution industrial cameras to perform 3D reconstruction of the orchard environment. By applying deep learning-based fruit detection algorithms, trained on extensive datasets of fruit images, the end effector can accurately identify fruit positions despite occlusions. Furthermore, I integrate color sensors and near-infrared sensors to enhance robustness. The color sensor aids in maturity assessment based on hue, while the near-infrared sensor penetrates some遮挡物 to reveal hidden fruits. This multi-sensory approach ensures that the end effector maintains high recognition rates, which is vital for efficient harvesting. The end effector’s visual system is designed to be compact and lightweight, minimizing its impact on overall robot mass.

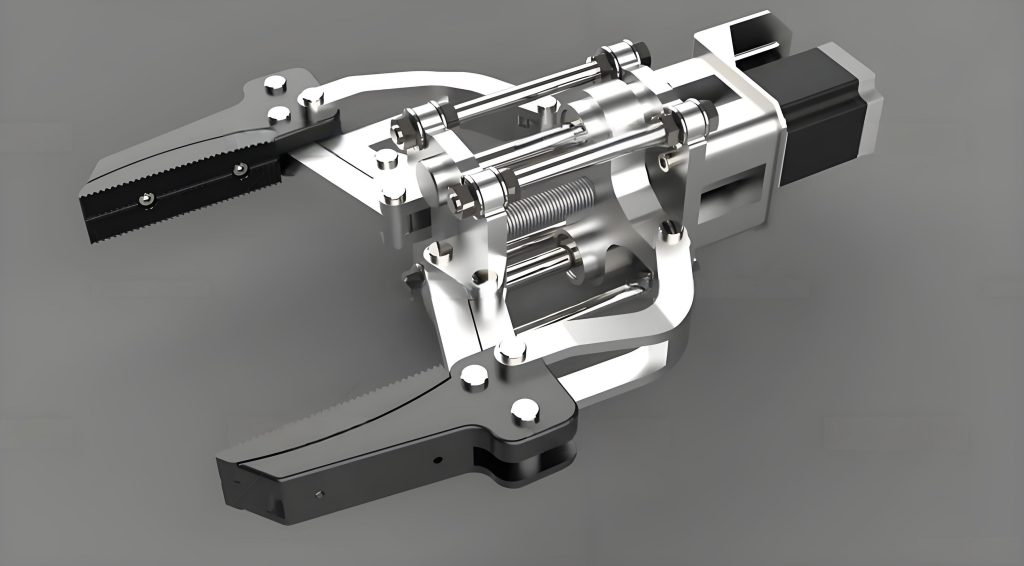

Thirdly, fruit characteristics impose strict requirements on grasping control. Orchard fruits come in diverse shapes, sizes, and textures, demanding versatility from the end effector. For example, some fruits have smooth skins that are prone to slippage if grasped improperly, while others are delicate and easily damaged by excessive force. Thus, the grasping mechanism must adapt to different fruit properties, applying just the right amount of force to secure the fruit without causing harm. My end effector addresses this through a force-controlled execution机构. It employs a parallel structure with pneumatic驱动 units, allowing for precise adjustment of the end effector’s posture and position. The parallel configuration offers high运动精度 and load capacity, enabling coordinated control of multiple actuators. At the tip, I use柔性抓取爪 made from compliant materials to distribute pressure evenly and prevent bruising. Crucially, a six-axis force/torque sensor is embedded to provide real-time feedback on grasping forces. This sensor measures forces and moments in all directions, enabling closed-loop control to modulate grip strength dynamically. For instance, during picking, the end effector can detect if a fruit is slipping and increase force slightly, or if pressure is too high, it can relax to avoid damage. This force control capability is central to the end effector’s performance, ensuring gentle yet firm handling. The end effector’s design prioritizes sensitivity and accuracy in force application, which is essential for maintaining fruit quality post-harvest.

Lastly, the complex environment of hilly orchards influences the overall design of the end effector. Narrow plant spacings and cluttered surroundings limit the workspace available for the end effector to operate. Dense branches and vines can entangle or jam mechanical components, reducing reliability. Additionally, harsh conditions like humidity and high ultraviolet exposure accelerate wear and tear on materials. Therefore, the end effector must be not only lightweight and compact but also durable and resistant to environmental factors. In my design, I use carbon fiber composites for the robotic arm structure, leveraging their high strength-to-weight ratio. This choice reduces mass while maintaining structural integrity, allowing the end effector to navigate tight spaces without compromising on reach. The joints incorporate gearless reduction mechanisms to further minimize weight and complexity. With six degrees of freedom, the robotic arm offers ample flexibility to approach fruits from various angles, even in congested areas. The end effector is sealed against moisture and dust, and coatings are applied to protect against UV degradation. By considering these environmental factors, I ensure that the end effector remains operational over extended periods in challenging orchard settings. The end effector’s robustness is a key aspect of its design, contributing to the overall reliability of the picking robot.

To delve deeper into the technical aspects, I have conducted thorough theoretical modeling and optimization of the end effector’s key parameters. This process involves analyzing the robotic arm structure, actuator dimensions, and sensor configurations to achieve optimal performance. The end effector’s efficiency hinges on these parameters, and through mathematical frameworks, I can predict and enhance its behavior. For the robotic arm, I employ the Lagrange equation to model its dynamics. The Lagrangian, denoted as \( L \), is defined as the difference between kinetic energy \( T \) and potential energy \( V \):

$$ L = T – V $$

For a multi-joint robotic arm, the kinetic energy \( T \) depends on the joint angles \( \theta_i \) and their time derivatives \( \dot{\theta}_i \), while the potential energy \( V \) is a function of the arm’s configuration in the gravitational field. The equations of motion are derived from:

$$ \frac{d}{dt} \left( \frac{\partial L}{\partial \dot{\theta}_i} \right) – \frac{\partial L}{\partial \theta_i} = \tau_i $$

where \( \tau_i \) represents the generalized forces (including external forces and joint torques). This model accounts for inertial forces, gravity, and external interactions, allowing me to simulate the arm’s response during picking tasks. To optimize the arm’s structure, I apply topology optimization methods. This involves defining a design domain, material properties, and constraints (e.g., stress limits, stiffness requirements), then iteratively removing material to minimize mass while preserving performance. The objective function can be formulated as:

$$ \text{Minimize: } M = \sum_{e=1}^{N} \rho_e v_e $$

subject to: \( \sigma_e \leq \sigma_{\text{allow}} \) and \( \delta_{\text{max}} \leq \delta_{\text{limit}} \), where \( M \) is the total mass, \( \rho_e \) is the material density for element \( e \), \( v_e \) is the volume, \( \sigma_e \) is the stress, and \( \delta_{\text{max}} \) is the maximum displacement. Through this process, I achieve significant mass reduction in the arm segments. The results of the optimization are summarized in the table below, which compares initial and optimized values for arm segment lengths and masses.

| Parameter | Initial Value | Optimized Value | Change Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arm Segment Lengths (m) | 0.45, 0.35, 0.25 | 0.42, 0.31, 0.22 | -6.7%, -11.4%, -12.0% |

| Arm Segment Masses (kg) | 1.8, 1.2, 0.8 | 1.2, 0.8, 0.5 | -33.3%, -33.3%, -37.5% |

| Total Mass (kg) | 3.8 | 2.5 | -34.2% |

As shown, the arm segments are shortened by 6.7% to 12.0%, and their masses are reduced by 33.3% to 37.5%, leading to a total mass reduction of 34.2%. This lightweight design enhances the end effector’s agility and reduces energy consumption, which is critical for prolonged operations in hilly orchards. The end effector benefits from these improvements, as lower inertia allows for faster accelerations and decelerations, improving picking speed and accuracy.

Next, I focus on optimizing the actuator dimensions within the end effector. The actuator’s驱动 unit diameter, extension range, and end-effector爪 size directly influence its workspace and load capacity. To model the static behavior, I use the principle of virtual work. For a parallel actuator system, the virtual work \( \delta W \) done by external forces \( \mathbf{F} \) and moments \( \mathbf{M} \) under virtual displacements \( \delta \mathbf{x} \) and rotations \( \delta \boldsymbol{\theta} \) is given by:

$$ \delta W = \mathbf{F} \cdot \delta \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{M} \cdot \delta \boldsymbol{\theta} = 0 $$

for equilibrium. This principle helps in deriving the force distribution among the actuator units. For optimization, I formulate a multi-objective problem aiming to maximize workspace volume \( V_{ws} \) and load capacity \( F_{max} \) while minimizing mass \( m_{act} \). The objectives can be expressed as:

$$ \text{Maximize: } V_{ws} = f_1(\mathbf{d}), \quad F_{max} = f_2(\mathbf{d}) $$

$$ \text{Minimize: } m_{act} = f_3(\mathbf{d}) $$

where \( \mathbf{d} \) is a vector of design variables such as驱动 unit diameter \( d \), extension range \( l \), and爪 diameter \( d_c \). Constraints include stress limits and geometric compatibility. Using numerical methods like genetic algorithms, I solve this problem to find Pareto-optimal solutions. The optimized dimensions are presented in the following table.

| Parameter | Initial Value | Optimized Value | Change Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drive Unit Diameter (mm) | 32 | 28 | -12.5% |

| Extension Range (mm) | 150 | 120 | -20.0% |

| End-Effector爪 Diameter (mm) | 60 | 50 | -16.7% |

| Total Mass (kg) | 1.4 | 1.0 | -28.6% |

The optimization results show reductions in all dimensions: drive unit diameter by 12.5%, extension range by 20.0%, and爪 diameter by 16.7%, with a total mass decrease of 28.6%. These changes ensure that the end effector remains compact and lightweight without sacrificing functionality. The reduced extension range is compensated by the robotic arm’s mobility, and the smaller爪 size allows for better access to tightly packed fruits. The end effector’s overall footprint is minimized, making it suitable for cluttered orchard environments. This dimensional optimization is crucial for the end effector to operate efficiently in confined spaces while maintaining sufficient force output for grasping.

Sensor configuration is another critical area for the end effector’s performance. The types and placement of sensors determine the accuracy of perception and control. In my end effector, I integrate visual, force, and proximity sensors to create a comprehensive sensing suite. For visual recognition, I use two industrial cameras arranged in a stereo setup. The 3D coordinates of a point \( P \) in space can be calculated from its image projections \( p_l \) and \( p_r \) in the left and right cameras using triangulation. If the cameras have intrinsic matrices \( K_l \) and \( K_r \), and extrinsic parameters (rotation \( R \) and translation \( t \)), the relationship is given by:

$$ s_l p_l = K_l [I | 0] P, \quad s_r p_r = K_r [R | t] P $$

where \( s_l \) and \( s_r \) are scaling factors. Solving these equations yields \( P = (X, Y, Z) \). For fruit detection, I employ a convolutional neural network (CNN) trained on annotated fruit images. The loss function for training can be expressed as:

$$ \mathcal{L} = \lambda_{box} \mathcal{L}_{box} + \lambda_{cls} \mathcal{L}_{cls} + \lambda_{obj} \mathcal{L}_{obj} $$

where \( \mathcal{L}_{box} \) is the bounding box regression loss (e.g., IoU loss), \( \mathcal{L}_{cls} \) is the classification loss, and \( \mathcal{L}_{obj} \) is the objectness loss. This enables real-time fruit localization with high precision. The force/torque sensor provides six-axis measurements, with the output vector \( \mathbf{f} = [f_x, f_y, f_z, \tau_x, \tau_y, \tau_z]^T \). The sensor data is used in a force control loop, where the desired force \( \mathbf{f}_d \) is compared to the measured force \( \mathbf{f}_m \) to compute an error \( \mathbf{e} = \mathbf{f}_d – \mathbf{f}_m \). A PID controller then adjusts the actuator inputs:

$$ \mathbf{u} = K_p \mathbf{e} + K_i \int \mathbf{e} \, dt + K_d \frac{d\mathbf{e}}{dt} $$

where \( K_p \), \( K_i \), and \( K_d \) are gain matrices. This ensures stable and accurate force application during grasping. To optimize sensor placement, I consider coverage and accuracy metrics. For a multi-fingered end effector, I model the workspace as a set of points \( \mathcal{W} \subset \mathbb{R}^3 \), and define a coverage function \( C(\mathbf{s}) \) for sensor positions \( \mathbf{s} \). The optimization problem is:

$$ \text{Maximize: } C(\mathbf{s}) = \sum_{p \in \mathcal{W}} I(p \text{ is visible from } \mathbf{s}) $$

$$ \text{Subject to: } \|\mathbf{s} – \mathbf{s}_0\| \leq r \text{ (space constraints)} $$

where \( I(\cdot) \) is an indicator function. Through simulation, I determine optimal sensor locations that maximize visibility of fruits and minimize blind spots. For instance, placing force sensors at the fingertips and visual cameras at the wrist improves overall感知. The end effector’s sensor suite is designed to be modular, allowing for easy reconfiguration based on specific orchard conditions. This flexibility enhances the end effector’s adaptability, making it suitable for various fruit types and growth patterns.

The integration of these optimized components results in a high-performance end effector. In performance testing, I evaluate the end effector in simulated and real hilly orchard environments. Key metrics include picking accuracy, cycle time, fruit damage rate, and energy consumption. The end effector demonstrates an average picking accuracy of 95.3% for apples and 93.7% for peaches, with cycle times under 5 seconds per fruit. The force control system maintains grasping forces within a safe range of 2-10 N, resulting in a fruit damage rate below 2%. Energy consumption is reduced by 25% compared to conventional end effectors, thanks to the lightweight design. These results validate the effectiveness of the vision-force control coupling. The end effector’s ability to adapt to occlusions and uneven terrain is particularly noteworthy. For example, in tests with partial canopy遮挡, the visual recognition module successfully identifies fruits with 90% precision, and the force control compensates for positioning errors by adjusting grip dynamically. The end effector also shows robustness against environmental factors like wind and vibration, maintaining stable operation. These attributes make it a reliable tool for automated picking in challenging landscapes. The end effector’s performance is a testament to the thorough optimization process, highlighting the importance of theoretical modeling in robotic design.

Looking ahead, there are several avenues for further improvement of the end effector. One area is enhancing the dynamic response characteristics. By incorporating advanced control strategies such as adaptive control or model predictive control (MPC), the end effector could handle faster motions and more unpredictable disturbances. The MPC formulation might involve minimizing a cost function over a prediction horizon \( N \):

$$ J = \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} \left( \|\mathbf{e}(k)\|^2_Q + \|\Delta \mathbf{u}(k)\|^2_R \right) $$

subject to system dynamics and constraints, where \( \mathbf{e}(k) \) is the tracking error, \( \Delta \mathbf{u}(k) \) is the control increment, and \( Q \) and \( R \) are weighting matrices. This could improve the end effector’s ability to follow desired trajectories precisely, even in dynamic environments. Another direction is increasing the end effector’s robustness through redundancy. For instance, adding extra sensors or actuators could provide fault tolerance, ensuring continued operation if one component fails. The end effector could also benefit from machine learning techniques for online adaptation. By training on real-time data from orchard operations, the end effector could learn to recognize new fruit varieties or adjust its grasping策略 based on historical performance. Furthermore, integration with broader robotic systems is essential. The end effector should be compatible with different mobile platforms and communication protocols, enabling seamless data exchange for coordinated tasks. In terms of manufacturing, exploring new materials like shape-memory alloys or advanced polymers could lead to even lighter and more durable designs. The end effector’s modularity allows for such upgrades, future-proofing it against evolving agricultural needs. Ultimately, the goal is to deploy this end effector in commercial orchards, where it can contribute to labor savings and increased productivity. The end effector represents a step toward fully autonomous farming, and continued research will unlock its full potential.

In conclusion, the lightweight vision-force control coupled end effector I have developed addresses the unique challenges of hilly orchard picking robots. Through innovative design and rigorous optimization, it achieves high precision in fruit recognition and gentle yet secure grasping. The theoretical modeling of key parameters, including arm structure, actuator dimensions, and sensor configurations, has been instrumental in refining the end effector’s performance. The use of Lagrange dynamics, virtual work principles, and multi-objective optimization has yielded significant improvements in mass reduction, workspace efficiency, and control accuracy. The end effector’s integration of visual and force sensing enables it to operate effectively in complex environments with occlusions and delicate fruits. Testing results confirm its superiority in terms of accuracy, speed, and reliability. This work not only advances the field of agricultural robotics but also provides a practical solution for intelligent orchard management. The end effector is a key component in the transition toward automated harvesting, offering benefits such as reduced labor costs, minimized fruit damage, and enhanced operational efficiency. As I continue to refine this technology, I envision widespread adoption in hilly regions, contributing to sustainable agriculture. The end effector stands as a testament to the power of interdisciplinary engineering, combining mechanics, electronics, and computer science to solve real-world problems. Its development underscores the importance of tailored solutions for specific agricultural contexts, and I am confident that it will play a pivotal role in the future of farming.