My work focuses on addressing the significant challenges in mechanizing the harvest of Camellia oleifera fruit, a crop of high economic and nutritional value in our region. The current reliance on manual picking is characterized by low efficiency, high labor intensity, and substantial cost, severely limiting industry expansion. Furthermore, the short optimal harvesting window compounds these difficulties. While mechanical solutions exist for other tree fruits, the unique biological characteristics of the Camellia plant—specifically, the concurrent presence of next year’s flower buds and mature fruit, and the complex, hilly terrain of its plantations—render common methods like trunk shaking or large-area combing unsuitable due to high bud damage and low fruit recovery rates.

Existing research into Camellia fruit harvesting mechanisms, including combing, vibrating, and roller-based systems, often applies a singular primary force (e.g., shear or impact). Given that the detachment force required for the fruit is greater than that for the fragile flower buds, these single-force methods struggle to achieve high harvest efficiency without concurrently causing unacceptable damage to the future crop yield. To overcome this fundamental limitation, I conceived and developed a novel end effector based on a twist-comb principle. This end effector is designed to apply a combination of forces—torsion, combing/shearing, and inertial force from branch relaxation—to detach the fruit more effectively while its physical configuration minimizes interaction with the smaller, more delicate buds and foliage.

The overall harvesting system integrates this specialized end effector with a mobile platform and positioning apparatus. The machine consists of a crawler-type mobile chassis, an electrical control cabinet, a fruit collection conveyor, and a multi-degree-of-freedom manipulator comprising lift, rotation, and extension mechanisms. The twist-comb end effector is mounted at the distal end of the telescopic arm. During operation, the machine is positioned adjacent to the Camellia tree. The manipulator first aligns the end effector, then extends it into the tree canopy. The end effector then grips a fruit-bearing branch and executes its compound harvesting motion. The harvested fruits fall onto the collection conveyor below.

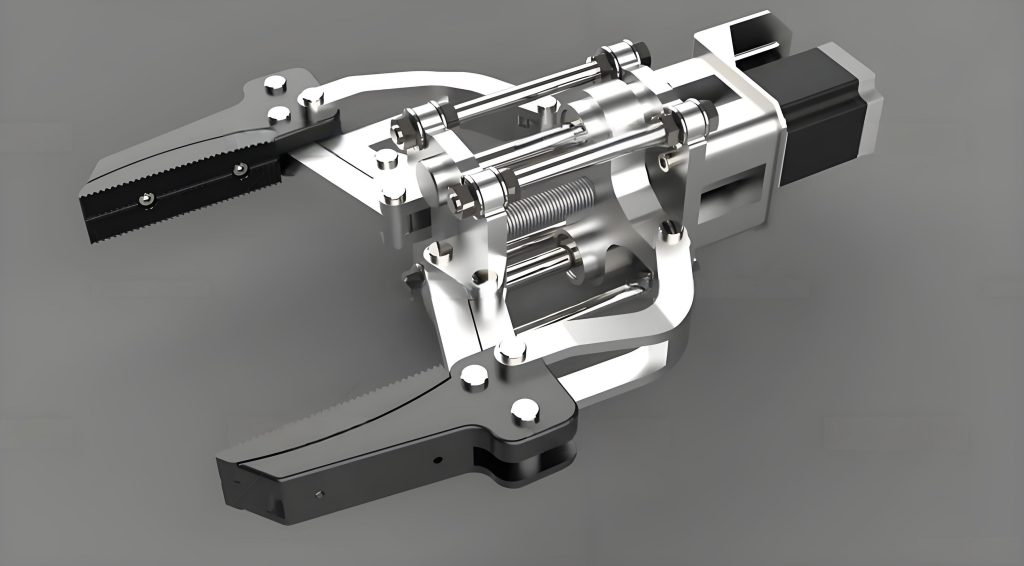

The core innovation lies in the design of the end effector itself. It primarily consists of two sub-assemblies: the twist-comb assembly and the comb-roller assembly. The twist-comb assembly features a bidirectional lead screw driven by a motor, which moves two opposing carriages along a guide rail. Each carriage is equipped with a set of robust, spaced “twist fingers.” A separate motor drives this entire assembly to oscillate through a set arc. The comb-roller assembly consists of two rotating rollers, one mounted on each carriage, positioned just above the twist fingers. Each roller is studded with flexible comb teeth and is independently driven by its own motor to oscillate. The key dimensional parameters were derived from biological measurements. The comb teeth are 30 mm long, spaced 70 mm apart vertically, with eight rows arranged in a staggered pattern around a 30 mm radius roller. The twist fingers are spaced 50 mm apart. This spacing is critical, as it allows branches to sit within the gaps, ensuring that the applied forces target the larger-diameter fruits while largely bypassing the smaller buds and leaves.

The working principle involves a coordinated, multi-phase action. Once the branch is gently clamped between the two carriages, both sub-assemblies activate. The twist-comb assembly rotates back and forth, applying a torsional force to the branch and the fruit stems. Simultaneously, the comb rollers rotate, with their teeth applying impacts, shear, and a secondary twisting action directly to the fruits. After a period of this combined action, the end effector releases its grip on the branch at the peak of its twist angle. The inherent elasticity of the branch causes it to snap back to its original position. This rapid relaxation generates a significant inertial force on the fruits. It is this synergistic application of multiple detachment forces—torsion from twisting, shear/impact from combing, and inertial jerk from relaxation—that enables high fruit removal while mitigating damage.

A detailed theoretical analysis of the fruit detachment process was conducted by examining the four primary action phases of the end effector. The forces involved are derived from fundamental mechanics. For instance, when a twist finger contacts a fruit, the normal force $F_{n1}$ and frictional force $F_{f1}$ applied can be expressed as:

$$F_{n1} = M_1 \omega_3^2 R_2 \cos(\alpha_2)$$

$$F_{f1} = \mu_1 F_{n1} = \mu_1 M_1 \omega_3^2 R_2 \cos(\alpha_2)$$

where $M_1$ is the mass of the twisting component, $\omega_3$ is its angular velocity, $R_2$ is the distance from the contact point to the center of rotation, $\alpha_2$ is the contact angle, and $\mu_1$ is the coefficient of friction.

Similarly, for the comb roller action, the forces on the fruit are:

$$F_{n2} = M_2 \omega_2^2 R_3 \cos(\alpha_3)$$

$$F_{f2} = \mu_2 F_{n2}$$

where the variables correspond to the comb roller’s mass $M_2$, angular velocity $\omega_2$, etc.

When both act simultaneously, the resultant forces $F_{n3}$ and $F_{f3}$ are the vector sums of the individual components. The fruit, modeled as a solid sphere, begins to rotate about its stem attachment point when the applied torque exceeds the stem’s resisting torque $M_A$. The equations of rotational motion are governed by:

$$J_1 \frac{d\omega_4}{dt} = \left(F_n – \frac{1}{2}F_A\right)L$$

$$J_2 \frac{d\omega_5}{dt} = F_f r – M_A$$

where $J_1$ and $J_2$ are moments of inertia for different axes, $\omega_4$ and $\omega_5$ are angular velocities, $F_A$ is the resultant stem binding force, and $L$ and $r$ are relevant moment arms.

Finally, during branch relaxation, the restoring shear stress $\tau$ within the twisted branch, based on torsion theory, is:

$$\tau = G \gamma = G \frac{\phi r_1}{l}$$

where $G$ is the shear modulus of the branch, $\gamma$ is the shear strain, $\phi$ is the twist angle, $r_1$ is the branch radius, and $l$ is the twisted length. This restoring force is what generates the final inertial jerk to detach the fruit. This analysis confirms that the key factors influencing fruit removal are the rotational speeds and angles of the end effector components, the fruit’s inherent shear and torsional binding strengths, and the torsional modulus and length of the branch.

The control system for this sophisticated end effector is built around an STM32 microcontroller. It manages the sequential and synchronized operations: positioning the carriages via the lead screw motor (with Hall effect sensors for limit detection), controlling the oscillatory motion of the twist-comb assembly through a dedicated motor driver, and governing the independent oscillations of the two comb rollers. A human-machine interface allows for parameter setting and operation monitoring. The software, developed in LabVIEW, implements a state-based control flow to ensure safe and repeatable harvesting cycles.

Prior to finalizing the end effector design, essential biological properties of Camellia were measured. The fruit-stem binding force—including tensile, shear, and torsional strengths—was tested for several common cultivars using digital push-pull gauges and a torque meter. The results are summarized below:

| Force Type | Typical Range | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Force | 10 N – 25 N | Greatest resistance to straight pull. |

| Shear Force | 5 N – 15 N | Lower resistance to lateral force. |

| Torsional Moment | 0.015 N·m – 0.030 N·m | Lowest resistance to twisting. |

These findings were crucial; they indicated that a twisting force would be the most efficient primary action for breaking the fruit stem, which directly informed the core principle of the end effector. Furthermore, the torsional properties of fruit-bearing branches were tested using a universal torsion machine. The shear modulus $G$ for different varieties was found to range between 2 MPa and 7 MPa. The tests also showed that branches undergo permanent plastic deformation if twisted beyond approximately 50°, which set the design limit for the oscillatory angle of the end effector to 48° to prevent damage to the tree.

| Tested Cultivar | Shear Modulus, G (MPa) | Maximum Safe Twist Angle |

|---|---|---|

| Changlin 4 | 3.52 | ≤ 50° |

| Changlin 40 | 6.79 | |

| Changlin 53 | 3.57 | |

| Xianglin 210 | 2.41 |

Performance evaluation of the prototype end effector was conducted on mature Changlin 53 cultivar trees. The primary metrics were Fruit Removal Rate ($P_1$) and Flower Bud Damage Rate ($P_2$), defined as:

$$P_1 = \frac{N_1 – N_3}{N_1} \times 100\%$$

$$P_2 = \frac{N_2 – N_4}{N_2} \times 100\%$$

where $N_1$ and $N_2$ are the initial counts of fruits and buds on a branch, and $N_3$ and $N_4$ are the counts remaining after the harvesting action.

Initial single-factor tests identified promising operational windows. The twist-comb assembly speed ($A$), comb-roller speed ($B$), and action time ($C$) were varied. Results indicated that a twist speed of 25–35 r/min, a comb speed of 75–85 r/min, and an action time of 8–12 s yielded a favorable balance between high fruit removal and low bud damage.

To determine the optimal parameter combination, a three-factor, three-level orthogonal experiment ($L_9(3^4)$) was designed within these ranges.

| Level | A: Twist Speed (r/min) | B: Comb Speed (r/min) | C: Action Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 75 | 8 |

| 2 | 30 | 80 | 10 |

| 3 | 35 | 85 | 12 |

The experimental results and range analysis are shown in the following table. For the fruit removal rate, the optimal levels were $A_3$, $B_3$, $C_3$. For bud damage rate, the optimal levels were $A_1$, $B_2$, $C_1$.

| Test No. | A | B | C | Fruit Removal Rate (%) | Bud Damage Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 70.75 | 8.95 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 72.76 | 9.21 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 83.25 | 11.36 |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 79.77 | 10.49 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 86.15 | 12.15 |

| 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 80.32 | 10.37 |

| 7 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 93.34 | 13.22 |

| 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 82.51 | 11.13 |

| 9 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 89.73 | 12.12 |

To reconcile the conflicting objectives of maximizing fruit removal and minimizing bud damage, a comprehensive scoring method was employed using weighted membership degrees. With a weight of 0.6 for removal rate and 0.4 for damage rate, the analysis yielded a clear optimal combination: $A_3B_3C_3$. This corresponds to a twist speed of 35 r/min, a comb speed of 85 r/min, and an action time of 12 s. The range analysis on the comprehensive score confirmed that twist speed (Factor A) had the most significant influence on overall performance, followed by comb speed (B) and action time (C).

Finally, verification tests were conducted using this optimal parameter set on the end effector. The results demonstrated the effectiveness of the design and the parameter optimization. Under these conditions, the twist-comb end effector achieved an average fruit removal rate of 93.37% with an average bud damage rate of 13.16%. This represents a significant performance improvement over mechanisms that apply only a single type of detachment force, successfully addressing the core challenge of selective harvesting in the presence of concurrent flower buds.

In summary, the developed twist-comb end effector presents a viable solution for mechanized Camellia fruit harvesting. Its innovative design applies a compound force action—torsion, combing, and inertial relaxation—derived from a thorough analysis of the fruit’s biological detachment characteristics. The strategic spacing of its active components minimizes harmful interaction with flower buds. Through systematic experimentation and optimization, a set of highly effective working parameters was identified. This end effector forms the core of a harvesting system that can potentially reduce labor dependency, lower costs, and support the sustainable expansion of the Camellia oil industry, marking a substantial advancement in the field of specialized agricultural robotics.