In the realm of precision manufacturing, such as semiconductor packaging and micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) assembly, the miniaturization of components and the demand for极致 assembly accuracy pose stringent challenges for robotic end effectors. Traditional methods relying solely on visual perception are susceptible to interference from surface glare and illumination fluctuations, leading to feature misdetection or pose calculation errors. Conversely, force-only control schemes lack spatial guidance, making it difficult to achieve precise control from coarse positioning to fine assembly, often resulting in jamming or damage due to part misalignment or substrate deformation. The fusion of vision and force sensing effectively突破es this technological bottleneck. Their synergy constructs a “perception-decision-execution” closed loop, enabling dual optimization of positional accuracy and contact compliance in precision assembly. To this end, we propose a design for a robotic vision-force fusion end effector tailored for precision assembly, aiming to overcome the limitations of traditional single-modal sensing and provide a solution that combines精度 and robustness for micro-nano scale assembly, thereby advancing automation in precision manufacturing.

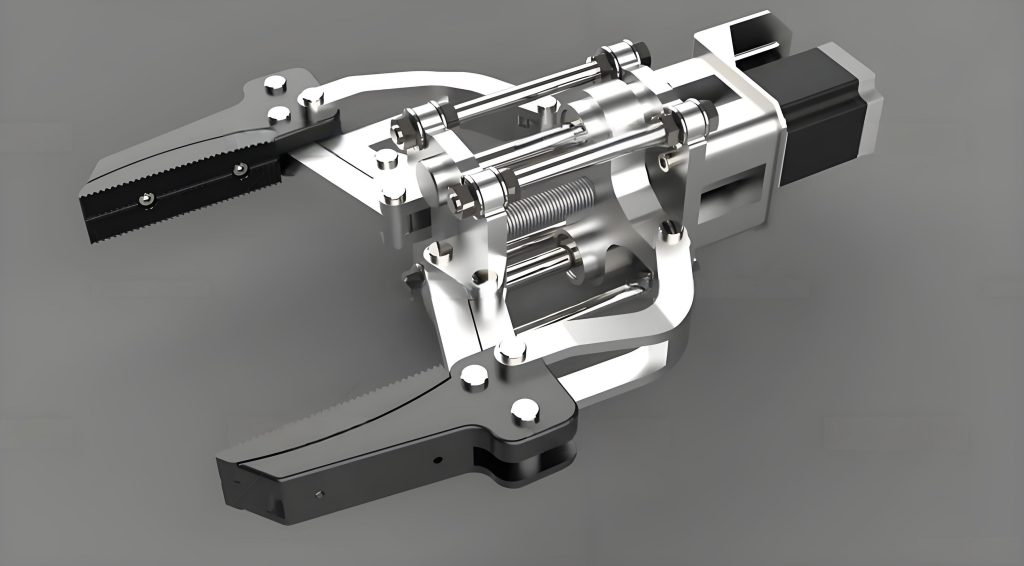

The overall architecture of our end effector adopts a modular design philosophy, comprising primarily a mechanical execution mechanism, vision module, force module, and data processing and control unit. Each module协同s through standardized interfaces. The mechanical execution mechanism is modularly designed, consisting of a grasping and motion mechanism. The grasping mechanism is equipped with an adaptive flexible gripper, with electric drive enabling adjustable clamping force. The motion mechanism integrates high-precision guides and a servo system, achieving sub-millimeter positioning accuracy to facilitate precise part movement and assembly. The vision module constructs a perception system using a high-resolution industrial camera, telecentric lens, and环形 LED light source. Through image processing algorithms, it achieves sub-pixel level定位 of the initial part pose and实时ly tracks changes in the assembly position. The force module employs a six-axis force sensor mounted at the mechanical end, measuring three-dimensional forces and moments in real-time. After signal processing, the data is transmitted to the control unit, providing contact force feedback for compliant assembly. The data processing and control unit, based on an embedded platform, synchronously acquires vision and force data, constructs an assembly model via multi-modal fusion algorithms, and employs adaptive control strategies to dynamically adjust the execution mechanism’s motion and grasping force, enabling precise control.

The hardware architecture of our end effector is meticulously designed to ensure high performance. The vision module utilizes a Basler acA2500-14gm industrial camera with a resolution of 2592 × 1944 pixels and a frame rate of 14 fps, meeting the need for rapid and clear imaging of parts in precision assembly. It is paired with a Computar M0814-MP2 8 mm fixed-focus lens, achieving a spatial resolution of 0.04 mm/pixel at a working distance of 200 mm. To ensure uniform illumination, a环形 LED light source with a wavelength of 520 nm and a color rendering index ≥90 is employed, effectively reducing image interference caused by part surface reflections. The force module incorporates an ATI Mini45 six-axis force sensor, capable of simultaneously measuring forces in the $F_x$, $F_y$, $F_z$ directions and moments $M_x$, $M_y$, $M_z$. Its force measurement range is ±50 N with a resolution of 0.01 N, and the moment measurement range is ±5 N·m with a resolution of 0.001 N·m. This sensor is installed at the end of the mechanical execution mechanism, accurately感知ing minute force variations during part assembly.

Data processing and control are critical for the functionality of the end effector. The visual定位 algorithm is implemented based on the OpenCV library, following a multi-stage processing pipeline. After applying a 5×5 Gaussian filter (standard deviation $\sigma=1.2$) to images captured by the industrial camera to suppress noise and smooth the image, histogram equalization enhances contrast, highlighting part edge features. In the feature extraction stage, the Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) algorithm generates 128-dimensional feature descriptors. After粗 matching between template and live images using a FLANN matcher, the RANSAC algorithm eliminates mismatched points, achieving pixel-level matching accuracy. Coordinate system transformation is based on Zhang’s calibration method. By capturing 10 sets of checkerboard calibration plates (grid size 20 mm × 20 mm) from different perspectives, nonlinear equations are solved to determine the camera intrinsic matrix $K$ and extrinsic matrix $[R|T]$, achieving calibration accuracy with intrinsic error <0.5% and extrinsic translation error <0.1 mm. The定位 mathematical model is given by:

$$ s \begin{bmatrix} u \\ v \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = K [R | T] \begin{bmatrix} X_w \\ Y_w \\ Z_w \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

where $(u, v)$ are pixel coordinates, $(X_w, Y_w, Z_w)$ are world coordinates, $f_x$, $f_y$ are focal lengths, $(c_x, c_y)$ are principal point coordinates, $s$ is a scale factor, and $R$, $T$ are the rotation matrix and translation vector, respectively. By establishing the transformation relationship between image pixel coordinates and world coordinates, the precise position and orientation of the part in the robot base coordinate system are obtained, providing a spatial coordinate基准 for assembly execution.

For force interaction, we implement an adaptive impedance force control strategy that dynamically adjusts stiffness and damping parameters to achieve compliant assembly. The basic control model is a second-order mass-spring-damper system:

$$ M\ddot{x} + B\dot{x} + Kx = F_d – F_e $$

where $M=0.5$ kg is the equivalent mass of the end effector, $K=1000$ N/m is the initial stiffness, $B=50$ N·s/m is the initial damping, $F_d$ is the desired force, $F_e$ is the measured force, and $x$ is the position deviation. The algorithm achieves parameter adaptive adjustment through online identification of environmental stiffness $K_e = \Delta F_e / \Delta x$. When a contact force $F_e > 0.5$ N is detected, if the environment is柔 ($K_e < 500$ N/m), $K$ is reduced to 200 N/m and $B$ is increased to 100 N·s/m; if rigid ($K_e \geq 500$ N/m), default parameters are maintained. The control cycle is set to 1 ms, and an emergency stop is triggered if the force deviation exceeds 1 N to prevent collision damage.

The core of our approach lies in the vision-force fusion design, which ensures coordinated perception. Vision-force spatiotemporal calibration aims to establish the transformation relationship between the vision coordinate system and the force coordinate system, ensuring that data from both modalities align within the same frame of reference. We employ a stepwise calibration method based on a planar target with高精度 feature points arranged规则ly (physical dimension error <0.01 mm). During calibration, the robot maneuvers the end effector to contact the target in various poses. The vision system acquires coordinates of feature points in the image coordinate system via sub-pixel edge detection algorithms, then converts them to 3D coordinates in the vision coordinate system using the camera intrinsic and extrinsic matrices. Simultaneously, the six-axis force sensor mounted on the end effector采集s contact forces $F_v$ and moments $M_v$. The rotation matrix $R$ (describing orientation difference) and translation vector $T$ (describing positional offset) are optimized via least squares to unify the two coordinate systems. The transformation for force and moment is expressed as:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} F_c \\ M_c \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} R & 0 \\ 0 & R \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} F_v \\ M_v \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ T’ \end{bmatrix} $$

where $F_c$, $M_c$ are the converted force and moment, $F_v$, $M_v$ are the measured force and moment, and $T’$ is the moment translation vector corrected via the cross product $T’ = T \times F_v$ to account for moment deviation due to non-coincident coordinate origins. This calibration process requires over 20 contact samples from different orientations,最终 achieving transformation errors of <0.05 mm in position and <0.5° in orientation, laying the groundwork for subsequent multi-modal data fusion.

Multi-modal data fusion employs a Kalman filter algorithm to integrate visual positioning information and force feedback. Let the system state vector be $X = [x, y, z, \theta_x, \theta_y, \theta_z, \dot{x}, \dot{y}, \dot{z}, F_x, F_y, F_z]^T$, representing position, orientation, velocity, and force components. The state transition and observation equations are:

$$ X_{k} = A X_{k-1} + B u_{k-1} + w_{k-1} $$

$$ Z_{k} = H X_{k} + v_{k} $$

where $A$ is the state transition matrix, $B$ is the control matrix, $u$ is the control input, $w$ is process noise, $H$ is the observation matrix, and $v$ is observation noise. By continuously updating the state estimate, accurate prediction of part position and force state is achieved, enhancing the robustness of the end effector during assembly.

To validate the performance of our vision-force fusion end effector, we constructed an experimental platform tailored for precision assembly tasks. The platform adopts a modular design encompassing execution, perception, control, and auxiliary tooling modules. The execution layer centers on a UR10e collaborative robot with a payload of 10 kg and repeatability of ±0.03 mm, communicating via an EtherCAT interface. The end effector integrates a Basler acA2500-14gm industrial camera with a Computar 8 mm telecentric lens, paired with an ATI Mini45 six-axis force sensor and a Pisco HGP-20 pneumatic gripper (10 mm stroke, ±0.02 mm positioning accuracy), achieving一体化 vision perception, force feedback, and precise grasping. The perception and control layer is based on an Advantech UNO-3083G industrial computer (Intel i7 processor, 16 GB RAM) running Ubuntu 20.04 and ROS Noetic. Vision data is transmitted via a Euresys GigE acquisition card (latency <5 ms), while force data is实时ly read by an ATI Gamma interface card (1 kHz sampling frequency). The lighting system uses a CCS green环形 LED (brightness adjustable 0%–100%), mounted on a Zolix three-axis位移 stage (0.01 mm precision) for multi-angle illumination. Auxiliary tooling includes a 300 mm × 300 mm granite base (flatness ≤5 μm), a porous ceramic vacuum吸附 platform (vacuum度 0–80 kPa), coupled with a Techman air spring vibration isolation system (vibration attenuation >90%) and an ionizing blower anti-static device (static dissipation <0.5 s), ensuring environmental stability. Software-wise, OpenCV implements vision algorithms, custom C++ libraries handle force control logic, the Eigen library optimizes Kalman filter matrix operations, and a Qt-based human-machine interface实时ly monitors assembly status. The test object is an 8 mm × 8 mm × 1 mm FR-4 chip, assembled into an 8.05 mm × 8.05 mm substrate slot with a target clearance of 0.05 mm (0.025 mm per side). The environment is controlled at (23±1)°C and 45%±5% RH to mitigate thermal deformation and electrostatic interference. This comprehensive platform, through high-precision hardware selection and real-time software control, provides reliable support for validating precision assembly algorithms.

We conducted 100 repeated assembly trials to evaluate the performance of our vision-force fusion end effector. The key performance indicators comparing the vision-force fusion algorithm with a vision-only定位 scheme are summarized in Table 1. The data clearly demonstrates that the fusion algorithm significantly enhances precision assembly performance. Under the fusion approach, the assembly success rate reaches 97%, with an average assembly time of (12.2 ± 1.5) s, mean force error of (0.32 ± 0.08) N, mean position error of (0.031 ± 0.005) mm, maximum force冲击 of 0.85 N, and assembly time standard deviation of 1.2 s. In contrast, the vision-only scheme achieves an 85% success rate, average assembly time of (18.7 ± 3.2) s, mean force error of (0.81 ± 0.21) N, mean position error of (0.082 ± 0.018) mm, maximum force冲击 of 2.12 N, and assembly time standard deviation of 2.8 s. The fusion algorithm exhibits clear advantages in success rate, efficiency, and control precision, underscoring the effectiveness of integrating force sensing with visual guidance in the end effector.

| Assembly Method | Success Rate (%) | Average Assembly Time (s) | Mean Force Error (N) | Mean Position Error (mm) | Max Force冲击 (N) | Assembly Time Std Dev (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vision-Force Fusion | 97 | 12.2 ± 1.5 | 0.32 ± 0.08 | 0.031 ± 0.005 | 0.85 | 1.2 |

| Vision-Only | 85 | 18.7 ± 3.2 | 0.81 ± 0.21 | 0.082 ± 0.018 | 2.12 | 2.8 |

To further illustrate the hardware specifications and algorithmic parameters of our end effector, we provide additional summaries in tabular form. Table 2 details the key components of the vision and force modules, highlighting their specifications that contribute to the high performance of the end effector. Table 3 outlines the parameters used in the adaptive impedance control model, which are crucial for the compliant behavior of the end effector during assembly.

| Component | Model/Specification | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Industrial Camera | Basler acA2500-14gm | Resolution: 2592×1944 pixels, Frame Rate: 14 fps |

| Lens | Computar M0814-MP2 | Focal Length: 8 mm, Spatial Resolution: 0.04 mm/pixel at 200 mm WD |

| Light Source | 环形 LED | Wavelength: 520 nm, CRI ≥90 |

| Force Sensor | ATI Mini45 | Force Range: ±50 N (Res: 0.01 N), Moment Range: ±5 N·m (Res: 0.001 N·m) |

| Gripper | Pisco HGP-20 | Stroke: 10 mm, Positioning Accuracy: ±0.02 mm |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equivalent Mass | $M$ | 0.5 kg | Mass of the end effector |

| Initial Stiffness | $K$ | 1000 N/m | Spring constant in impedance model |

| Initial Damping | $B$ | 50 N·s/m | Damping coefficient in impedance model |

| Force Threshold | $F_{th}$ | 0.5 N | Threshold for triggering adaptive adjustment |

| Stiffness for柔 Environment | $K_{soft}$ | 200 N/m | Adjusted stiffness when $K_e < 500$ N/m |

| Damping for柔 Environment | $B_{soft}$ | 100 N·s/m | Adjusted damping when $K_e < 500$ N/m |

| Control Cycle | $T_c$ | 1 ms | Sampling period for force control loop |

| Emergency Force Deviation | $\Delta F_{emerg}$ | 1 N | Force deviation triggering emergency stop |

The mathematical foundation of our vision-force fusion end effector extends beyond basic models. The Kalman filter used for multi-modal fusion involves detailed matrix operations. The state transition matrix $A$ and observation matrix $H$ are derived based on the dynamics of the end effector and the measurement models. For instance, assuming constant velocity model for position and orientation, and力 dynamics modeled as first-order systems, we can define:

$$ A = \begin{bmatrix} I_{6\times6} & \Delta t \cdot I_{6\times6} & 0_{6\times3} \\ 0_{6\times6} & I_{6\times6} & 0_{6\times3} \\ 0_{3\times6} & 0_{3\times6} & \alpha \cdot I_{3\times3} \end{bmatrix} $$

where $\Delta t$ is the sampling time, $I$ is identity matrix, and $\alpha$ is a forgetting factor for force states. The observation matrix $H$ selects appropriate states based on available sensor data:

$$ H = \begin{bmatrix} I_{6\times6} & 0_{6\times6} & 0_{6\times3} \\ 0_{3\times6} & 0_{3\times6} & I_{3\times3} \end{bmatrix} $$

assuming vision provides position/orientation and force sensor provides force measurements. The process noise $w$ and observation noise $v$ are modeled as zero-mean Gaussian with协方差 matrices $Q$ and $R$, respectively, tuned empirically to reflect uncertainties in the end effector’s motion and sensor readings.

In the context of precision assembly, the end effector must handle various edge cases. For example, when dealing with highly reflective surfaces, the vision module may experience saturated pixels. To mitigate this, we incorporate an adaptive exposure control algorithm in the camera settings, dynamically adjusting based on image histogram analysis. For the force module, temperature drift compensation is applied to the six-axis sensor readings using a built-in temperature sensor and a linear correction model:

$$ F_{corrected} = F_{raw} – \beta (T – T_0) $$

where $\beta$ is a drift coefficient, $T$ is the current temperature, and $T_0$ is a reference temperature. This ensures that the force feedback from the end effector remains accurate under varying environmental conditions.

The modular design of our end effector facilitates maintenance and upgrades. Each module—mechanical, vision, force, and control—can be independently replaced or enhanced without overhauling the entire system. For instance, if a higher-resolution camera becomes available, it can be integrated by simply updating the calibration parameters and software drivers, ensuring that the end effector remains state-of-the-art. This modularity also allows for customization based on specific assembly tasks, such as swapping the gripper for a vacuum suction cup for handling fragile components.

Looking ahead, several avenues exist for improving the vision-force fusion end effector. One direction is the integration of深度学习 techniques for more robust feature detection and matching in the vision module. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) could be trained to识别 parts under varying lighting conditions, reducing reliance on controlled illumination. The force control strategy could also benefit from model predictive control (MPC) algorithms that optimize trajectories while respecting force constraints. Furthermore, the fusion algorithm could be extended to incorporate additional sensing modalities, such as tactile sensors or proximity sensors, to enhance the end effector’s perception capabilities. Research into reducing the latency between sensing and actuation will also be crucial for high-speed precision assembly, potentially involving field-programmable gate array (FPGA) implementations for real-time processing.

In conclusion, the vision-force fusion end effector we designed, through hardware modular integration and algorithmic协同 optimization, demonstrates significant performance advantages in precision assembly experiments. The results confirm that this end effector effectively addresses the limitations of traditional single-modal sensing approaches, substantially improving assembly success rate, efficiency, and control precision. The end effector’s ability to seamlessly integrate visual guidance with force feedback represents a significant step forward in robotic assembly systems. Future work will focus on深度抑制 sensor noise, optimizing adaptive multi-modal data fusion schemes in dynamic environments, and exploring advanced control paradigms to further enhance the adaptability and reliability of the end effector in industrial scenarios, thereby driving the intelligent升级 of precision assembly technology. The continuous evolution of such end effectors will play a pivotal role in meeting the growing demands of modern manufacturing for higher accuracy, flexibility, and autonomy.