The pursuit of mechanized and intelligent solutions for agriculture is a driving force in modern robotics. Citrus harvesting, a labor-intensive and costly process, stands to benefit immensely from such automation. A critical component in this endeavor is the robotic end effector—the hand of the harvesting robot. Its primary challenge is to securely grasp and detach fruits of varying sizes and shapes without causing bruising or puncture damage to the delicate peel. This paper presents the design, analysis, and experimental validation of a novel underactuated three-fingered end effector specifically engineered for this task. Our end effector combines passive compliance for size adaptation with active compliance for shape conformity, achieving stable, non-damaging picks.

Traditional robotic grippers often lack the adaptability required for the natural variance found in orchards. Our design philosophy draws inspiration from human dexterity, which employs both enveloping “power grasps” for larger fruit and precision “pinch grasps” for smaller ones. We translate this capability into a mechanically elegant, underactuated system. Underactuation, where the number of actuators is fewer than the degrees of freedom, provides inherent passive compliance and shape adaptation while simplifying control and reducing weight and cost. The core innovation of our end effector lies in the fusion control of finger flexion and independent finger-base rotation, allowing it to conform not just to different sizes but also to the elliptical cross-sections common in citrus fruit.

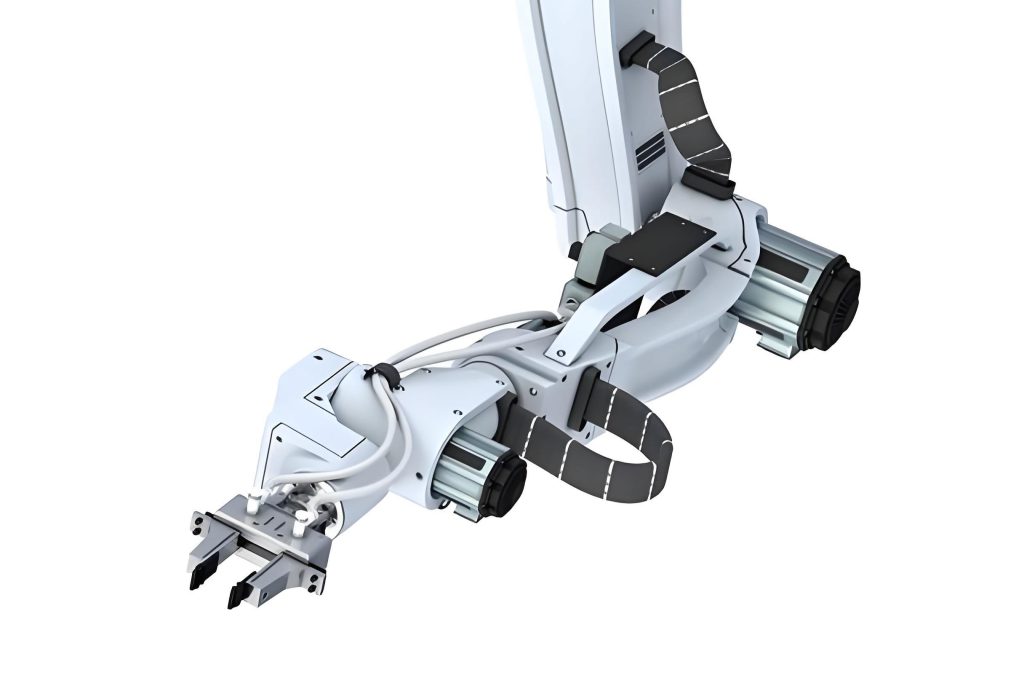

The overall architecture of the harvesting end effector consists of three identical fingers symmetrically mounted at 120-degree intervals on a central palm (or base) structure. The system is driven by four motors in total: one motor dedicated to the flexion/extension of all three fingers via a synchronized mechanism, one motor for the axial rotation of each finger base (three motors total for this function), and a final motor in the wrist to rotate the entire end effector for the twisting detachment motion. The finger structures and palm housing are fabricated using lightweight 3D printing, and the inner surfaces of the fingers are lined with soft silicone rubber to increase friction and cushion the fruit.

1. Design of the Dual-Link Parallel Underactuated Finger

The finger is the cornerstone of the end effector’s adaptability. Each finger is a three-phalange underactuated mechanism designed to perform both enveloping and pinching grasps autonomously based on the object’s size and contact points.

1.1 Flexion Mechanism and Grasping Modes

To achieve underactuation and dual-grasping-mode capability, we designed a novel dual-link parallel finger structure. The mechanism incorporates two sets of four-bar linkages within the proximal phalanx: a primary driving linkage and a secondary following linkage. The joints between phalanges are connected via low-friction pivot pins. A torsion spring and a mechanical stop work in concert with the secondary linkage to maintain the orientation of the distal phalanx during specific phases of movement.

The grasping sequence for a large-diameter fruit (enveloping grasp) is as follows:

1. The finger begins closing from its open position.

2. The distal phalanx first contacts the fruit surface. The reaction force halts its motion.

3. The driving linkage continues, causing the middle phalanx to rotate and conform to the fruit’s surface until it too makes contact.

4. Finally, the proximal phalanx rotates, bringing the entire inner finger surface into contact with the fruit, achieving a stable, form-closed enveloping grasp.

For a small-diameter fruit (pinching grasp), the sequence differs:

1. The finger closes, but neither the distal nor middle phalanges contact the fruit.

2. The secondary linkage, in conjunction with the torsion spring and stop, constrains the motion. This causes the distal and middle phalanges to move almost as a rigid body, translating rather than rotating.

3. The pad of the distal phalanx makes contact with the small fruit, executing a stable two-point pinch grasp. Without the secondary linkage, the fingertip would splay outward, failing to secure the object.

1.2 Static Force Analysis of Finger Flexion

To size the flexion motor and understand the force transmission, a static analysis of the finger during an enveloping grasp is performed. We apply the principle of virtual work. When all three phalanges are in contact with the fruit, the finger’s configuration is fully constrained by the contact points \(c_1, c_2, c_3\).

The principle of virtual work states:

$$ \mathbf{T}^T \boldsymbol{\omega} = \mathbf{F}^T \mathbf{V} $$

where:

- \(\mathbf{T} = [T_1, T_2, T_3]^T\) is the vector of input torques at the joints.

- \(\boldsymbol{\omega} = [\dot{\theta}_1, \dot{\alpha}_2, \dot{\alpha}_3]^T\) is the vector of corresponding virtual angular velocities.

- \(\mathbf{F} = [F_1, F_2, F_3]^T\) is the vector of contact forces (normal to the phalanges).

- \(\mathbf{V} = [v_1, v_2, v_3]^T\) is the vector of virtual velocities at the contact points in the direction of \(\mathbf{F}\).

The contact point velocities are related to the joint angular velocities through a velocity Jacobian matrix \(\mathbf{J}_v\):

$$ \mathbf{V} = \mathbf{J}_v \dot{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}, \quad \text{where} \quad \dot{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} = [\dot{\alpha}_1, \dot{\alpha}_2, \dot{\alpha}_3]^T $$

For the three-phalanx finger, the Jacobian can be derived from geometric analysis:

$$

\mathbf{J}_v = \begin{bmatrix}

l_1 & 0 & 0 \\

l_2 + d_1 \cos \alpha_2 & l_2 & 0 \\

l_3 + d_1 \cos(\alpha_2+\alpha_3) + d_2 \cos \alpha_3 & l_3 + d_2 \cos \alpha_3 & l_3

\end{bmatrix}

$$

where \(d_1, d_2, d_3\) are the link lengths, and \(l_i\) is the distance from the joint to the contact point on phalanx \(i\).

The relationship between the drive joint velocity \(\dot{\theta}_1\) and the phalanx joint velocities \(\dot{\alpha}_i\) is found using instant center analysis, leading to a transformation matrix \(\mathbf{J}_{\omega}\):

$$ \dot{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} = \mathbf{J}_{\omega} \boldsymbol{\omega} $$

Combining these, the force-torque relationship is derived as:

$$ \mathbf{F} = ( \mathbf{J}_v \mathbf{J}_{\omega} )^{-T} \mathbf{T} $$

This analysis allows us to determine the required motor torque \(T_{motor}\) to achieve a desired, non-damaging gripping force \(F_c\) at the contact points, considering the gear reduction and lead of the transmission system:

$$ T_{motor} = \frac{H \cdot L \cos \phi}{2\pi \cdot d \cdot \eta} F_c $$

where \(H\) is the lead, \(L\) is the lever arm, \(\phi\) is the transmission angle, \(d\) is the gear pitch diameter, and \(\eta\) is the efficiency.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (mm or deg) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal Phalanx Length | \(d_1\) | 45 | Length of finger base link |

| Middle Phalanx Length | \(d_2\) | 35 | Length of middle finger link |

| Distal Phalanx Length | \(d_3\) | 30 | Length of fingertip link |

| Max Enveloping Diameter | \(D_{max}\) | 100 | Maximum fruit diameter for full grasp |

| Min Pinching Diameter | \(D_{min}\) | 30 | Minimum fruit diameter for stable pinch |

| Target Grip Force | \(F_c\) | 8 – 12 N | Per-finger normal force range |

2. Active Compliance via Finger-Base Rotation

While the underactuated flexion provides passive compliance to size, citrus fruits often have elliptical cross-sections. A rigid, symmetrically converging three-finger grasp on an ellipse results in non-conforming contacts. The contact force vectors do not intersect at a common point, leading to an unstable grasp that is not force-closed. Furthermore, the sharp edges of the finger pads can dig into the fruit peel, causing damage.

To solve this, we introduce an active degree of freedom at the base of each finger—a rotation joint about the finger’s longitudinal axis. The control objective for this joint is to rotate the finger so that its inner contact surface becomes parallel (tangent) to the local surface of the elliptical fruit. This maximizes the contact area, aligns the normal force, and brings the system closer to a stable, force-closed grasp while preventing edge contact.

2.1 Mechanics of Rotation and Control Principle

When a finger pad contacts an elliptical fruit at a non-tangential angle, the friction force generates a moment \(T_i\) about the finger’s longitudinal axis at the base joint. This disturbance torque is sensed indirectly. We employ a DC servo motor with current feedback at each finger-base joint. The fundamental relationship for a DC motor is:

$$ T_e = K_t \cdot I_a $$

where \(T_e\) is the electromagnetic torque, \(K_t\) is the torque constant, and \(I_a\) is the armature current. Under steady-state conditions with no external torque, the current draw is minimal when the finger is holding a position. When an external disturbance torque \(T_{dist}\) acts on the joint (like the misalignment torque from grasping an ellipse), the motor must generate an equal and opposite torque to maintain position, resulting in a measurable increase in armature current \(\Delta I\):

$$ T_{dist} = K_t \cdot \Delta I $$

Thus, the current error signal \(\Delta I\) is directly proportional to the misalignment torque. Our control strategy uses this \(\Delta I\) as the primary feedback signal to drive the finger-base rotation until \(\Delta I\) is minimized, i.e., until the misalignment torque \(T_{dist}\) is eliminated, indicating the pad is tangent to the surface.

2.2 Servo Control System Model and Strategy

The dynamic model of the finger-base joint servo system is derived from the DC motor equations and mechanical load. The electrical equation is:

$$ U_a(s) = I_a(s)R_a + L_a s I_a(s) + K_e \Omega(s) $$

The mechanical equation is:

$$ T_e(s) = K_t I_a(s) = J s \Omega(s) + B \Omega(s) + T_{dist}(s) $$

where:

- \(U_a\): Armature voltage

- \(R_a, L_a\): Armature resistance and inductance

- \(K_e\): Back-EMF constant

- \(\Omega\): Motor angular velocity

- \(J, B\): Total inertia and damping at the joint

- \(T_{dist}\): Disturbance torque (misalignment torque)

Combining these and solving for the armature current \(I_a(s)\) yields:

$$ I_a(s) = \frac{J s U_a(s) + K_e T_{dist}(s)}{J L_a s^2 + (J R_a + B L_a) s + (B R_a + K_e K_t)} $$

When perfectly aligned, \(T_{dist}=0\), and the nominal current \(I_d(s)\) is:

$$ I_d(s) = \frac{J s U_a(s)}{J L_a s^2 + (J R_a + B L_a) s + (B R_a + K_e K_t)} $$

Therefore, the current deviation due to misalignment is:

$$ \Delta I(s) = I_a(s) – I_d(s) = \frac{K_e}{J L_a s^2 + (J R_a + B L_a) s + (B R_a + K_e K_t)} T_{dist}(s) $$

This \(\Delta I(s)\) is fed into a digital PID controller. The controller output adjusts the PWM duty cycle \(u(k)\) to the motor driver, rotating the joint to nullify the disturbance. The incremental digital PID output is:

$$ \Delta u(k) = K_p [e(k)-e(k-1)] + K_i e(k) + K_d [e(k)-2e(k-1)+e(k-2)] $$

where \(e(k) = \Delta I(k)\) is the current error at the \(k\)-th sample. This strategy provides the active compliance necessary for the end effector to conform to non-spherical fruit shapes gently and automatically.

| Component/Parameter | Specification/Value |

|---|---|

| Actuator | DC Geared Servo Motor |

| Gear Reduction Ratio | 298:1 |

| Stall Torque | 1.2 Nm |

| Position Feedback | Integrated Potentiometer |

| Primary Control Feedback | Armature Current (via H-bridge driver sense resistor) |

| Control Algorithm | Digital PID on Current Error (\(\Delta I\)) |

| Rotation Range | ± 30 degrees |

| Sampling Frequency | 1 kHz |

3. System Integration and Harvesting Procedure

The complete end effector system integrates the mechanical design with the control electronics. A central microcontroller coordinates all four motors. The harvesting sequence is as follows:

- Approach and Pre-rotation: The robotic arm positions the end effector around the target fruit. Based on a preliminary visual estimate of fruit ellipticity, the finger-base motors perform an initial coarse rotation to approximate alignment.

- Grasping Phase: The flexion motor is activated, closing the three underactuated fingers. They conform to the fruit’s size via passive adaptation (enveloping or pinching). Simultaneously, the finger-base joint controllers actively monitor current. They continuously adjust each finger’s rotation to minimize \(\Delta I\), ensuring pad tangency and stable force closure.

- Detachment Phase: Once a stable grip is confirmed (e.g., by checking if flexion motor current has reached a threshold corresponding to the target grip force), the wrist rotation motor is engaged. It applies a gentle torsional force, mimicking the human “twist-and-pick” motion, to sever the fruit stem.

- Release and Reset: The fruit is transported to a collection bin, the fingers open, and all joints reset to their default positions for the next harvest cycle.

4. Simulation and Experimental Validation

4.1 Kinematic Simulation

Prior to physical prototyping, the finger’s kinematics were simulated. The simulations validated the dual-grasping-mode functionality, confirming that the dual-link parallel mechanism successfully enables both enveloping grasps for spheres up to 100 mm and precision pinches for spheres as small as 30 mm. The simulations also confirmed the required range of motion for the base rotation joints to accommodate typical citrus elliptical cross-sections.

4.2 Physical Prototype and Laboratory Experiments

A full-scale prototype of the end effector was manufactured. Laboratory tests were conducted using a variety of citrus fruits (oranges, mandarins) with diameters ranging from 30 mm to 100 mm and varying ellipticity. The fruits were presented in a fixed position, and the end effector, mounted on a test stand, executed the harvesting sequence.

Grasping Success: The end effector demonstrated remarkable adaptability. For large spherical fruit, it consistently performed enveloping grasps with all phalanges making contact. For small fruit, it reliably switched to a two-point pinch using the distal phalanges. The active base rotation was clearly observable when grasping oval-shaped mandarins; each finger independently rotated to “seat” itself properly against the fruit surface.

Harvesting Trials: Three separate batches of fruit were used for quantitative testing. The primary metrics were success rate (non-damaging pick and hold) and cycle time. The results are summarized below:

| Batch | Number of Picks Attempted | Successful Picks | Damaged Fruits | Average Cycle Time per Fruit (s) | Success Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 98 | 2 | 6.1 | 98.0 |

| 2 | 132 | 129 | 3 | 5.5 | 97.7 |

| 3 | 112 | 111 | 1 | 4.5 | 99.1 |

| Average / Total | 115 | 113 | 2 | 5.3 | 98.3 |

The damage observed was primarily due to pre-existing minor bruises or overly soft, overripe fruit, not from the mechanism itself. The average successful harvesting cycle time was 5.3 seconds in a controlled lab setting. This demonstrates the practical efficacy of the proposed end effector design.

5. Conclusion

This paper presented the complete development of a novel underactuated end effector for robotic citrus harvesting. The key contributions are:

- Dual-Mode Underactuated Finger: The double-link parallel finger design provides inherent passive compliance, allowing a single actuator to achieve both stable enveloping and pinching grasps across a wide size range (30-100 mm).

- Active Shape Conformity: The addition of an independently controlled rotational degree of freedom at each finger base, paired with a current-feedback-based active compliance control strategy, enables the end effector to conform to non-spherical fruit shapes. This maximizes contact area, ensures stable force closure, and prevents damage from edge contact.

- Integrated System Performance: The fusion of these two compliance strategies in a three-fingered architecture results in an end effector that is mechanically simpler and more cost-effective than fully actuated dexterous hands, yet highly effective for its targeted agricultural task.

Experimental validation on real citrus fruit confirmed a high success rate of 98.3% and demonstrated the practical feasibility of the design. The proposed end effector represents a significant step toward reliable, non-damaging, and efficient robotic harvesting of citrus and other similarly delicate, variable-shaped produce. Future work will focus on integrating the end effector with a machine vision system and a mobile manipulator for full in-orchard testing and optimization of the complete harvesting cycle.