In the modern manufacturing landscape, the demand for precision and efficiency in producing electronic components has never been higher. Sheet metal parts constitute approximately 40% of electronic product components, prized for their ease of forming and stability. However, traditional automation solutions, particularly robotic end effectors, often fall short when faced with the multi-batch, small-lot production patterns typical of the electronics industry. Existing suction grippers, while effective for larger, standardized parts in sectors like automotive, struggle with the diversity and small sizes of electronic sheet metal components. Moreover, issues such as oxide layer shedding during bending—which contaminates molds and compromises quality—remain unaddressed by conventional designs. To tackle these challenges, I have developed a multifunctional flexible end effector tailored for robotic sheet metal bending in electronic products. This end effector not only adapts to varied part geometries but also integrates cleaning capabilities, enhancing overall system performance. In this article, I will delve into the design, control, analytical models, and practical applications of this innovative end effector, emphasizing its flexibility and efficiency through detailed formulas and tables.

The core innovation lies in the end effector’s ability to handle diverse part sizes without requiring multiple specialized tools. Traditional end effectors rely on rigid frames with fixed suction cups, necessitating separate grippers for different parts—a costly and inefficient approach for low-volume production. My design incorporates adjustable components that allow rapid reconfiguration, reducing downtime and tooling expenses. Additionally, the integration of a mold cleaning head directly addresses the oxide debris problem, a common pain point in sheet metal processing. Throughout this discussion, I will refer to the end effector as a key enabler of automation, highlighting its role in improving precision and throughput. The following sections will explore the technical underpinnings, from structural mechanics to control algorithms, supported by mathematical derivations and empirical data.

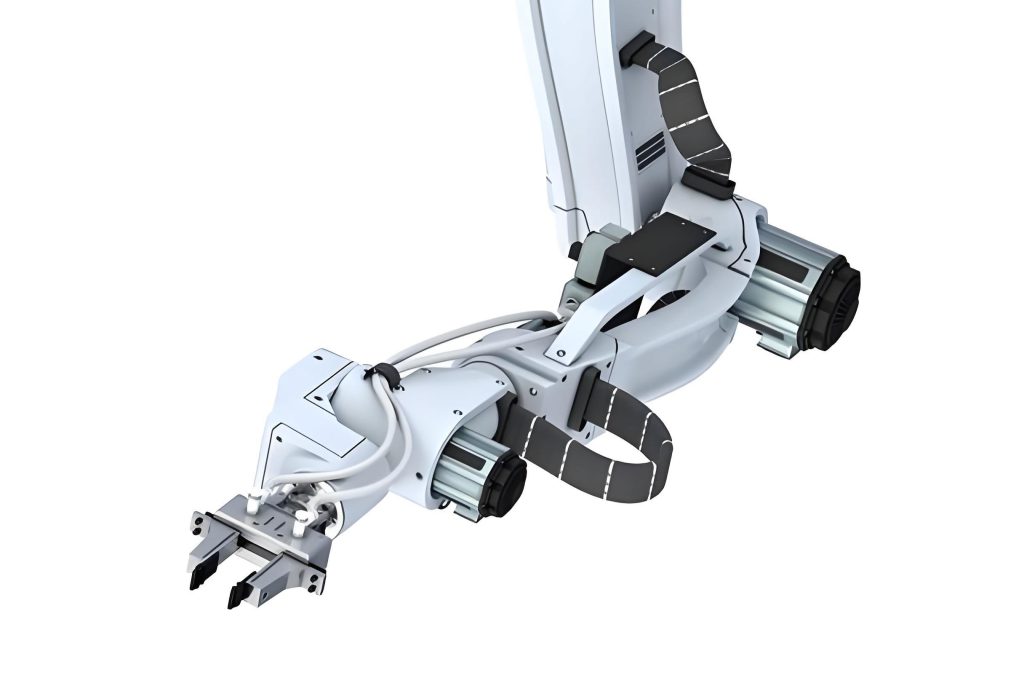

The structural design of the multifunctional flexible end effector is centered on modularity and adaptability. As shown in the image, the end effector features a vacuum suction cup system mounted on adjustable brackets that can rotate around tunable bolts. This rotation capability, typically up to 30 degrees, allows the suction cups to conform to non-flat or angled surfaces common in electronic parts. The X and Y-direction drag chain components are positionally adjustable via linear guides, enabling precise alignment of the gripping point with the part’s center of mass. This is critical for maintaining stability during handling, especially for small, delicate components. A quick-release mechanism at the top facilitates rapid attachment and detachment from the robot arm, complying with standard robotic interface specifications (e.g., ISO 9409-1-50-4-M6). This ensures compatibility with various industrial robots, enhancing the end effector’s versatility. Furthermore, the integrated mold cleaning head, positioned adjacent to the suction cups, utilizes the robot’s mobility to sweep away oxide residues from bending dies, preventing accumulation that could affect part quality. The entire end effector is constructed from lightweight aluminum alloys to minimize inertial loads on the robot, while maintaining rigidity for precise operations.

To quantify the adjustability, consider the following table summarizing key structural parameters of the end effector:

| Component | Adjustment Range | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Suction Cup Rotation | ±30° | Adapt to part geometry |

| X-Direction Drag Chain | 0-200 mm | Center gripping point |

| Y-Direction Drag Chain | 0-150 mm | Center gripping point |

| Quick-Release Interface | Standard ISO flange | Fast robot mounting |

| Cleaning Head Reach | 50 mm | Mold debris removal |

The control system for this flexible end effector is designed to orchestrate multiple degrees of freedom seamlessly. It interfaces with a central programmable logic controller (PLC) and an industrial computer (IPC) that manage the entire bending cell. The end effector’s movements—including X and Y linear adjustments, suction cup rotation, and vacuum pressure control—are governed by synchronized motor drives and pneumatic valves. A key aspect is the sequential logic: the positioning motions (X, Y, rotation) must complete before the vacuum is engaged to ensure secure gripping. This is implemented via ladder logic in the PLC, as illustrated in the delay-start functionality. For instance, after adjusting the end effector to a new part configuration, a timer delays vacuum activation by 0.5 seconds, preventing premature suction that could misalign the part. The control software, developed in C++, allows both manual operation and automated sequences, integrating with robot path planning for bending follow-up motions. The end effector’s sensors, such as proximity switches and pressure transducers, provide real-time feedback to the PLC, enabling adaptive control. For example, if a part is detected as misaligned, the system can retract and reposition the end effector automatically.

In sheet metal bending, understanding material deformation is essential for precision. During V-die bending, the metal undergoes elastic-plastic strain, causing elongation on the outer surface and compression on the inner surface. This phenomenon, illustrated by grid distortion, directly impacts the accuracy of the bent part. The neutral axis, where no strain occurs, shifts inward depending on material properties and thickness. The elongation Δl of the outer layer relative to the neutral layer can be expressed mathematically. Let α denote the bend angle in radians, r the bend radius, h the sheet thickness, and K the neutral axis factor (typically 0.3-0.5 for metals like aluminum). The elongation is given by:

$$\Delta l = \alpha (r + h) – \alpha (r + K h) = \alpha h (1 – K)$$

This formula highlights that deformation increases with bend angle and thickness, but decreases with higher K values. For electronic sheet metals, which are often thin (h < 2 mm) and bent at small angles (α < 90°), Δl can range from 0.1 to 1 mm—significant enough to affect dimensional tolerances. The neutral axis factor K depends on material ductility and bending conditions; empirical values for common electronics materials are tabulated below:

| Material | Thickness h (mm) | Neutral Axis Factor K | Typical Δl for α=90° (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum 5052 | 1.0 | 0.35 | 0.41 |

| Stainless Steel 304 | 1.5 | 0.45 | 0.42 |

| Copper C11000 | 0.8 | 0.30 | 0.50 |

| Brass C36000 | 1.2 | 0.40 | 0.54 |

To compensate for this deformation during robotic bending, I developed a pose compensation algorithm. In a typical bending sequence, the robot arm holds the sheet metal via the end effector and follows the die movement. Without compensation, the end effector’s fixed position would either stretch or compress the sheet, leading to springback errors or wrinkles. The goal is to adjust the end effector’s pose dynamically so that its holding point moves in sync with the material’s natural deformation. Consider the initial gripping point m0 in world coordinates. After bending, the ideal point m1 is where the sheet should be if no deformation occurred, but due to elongation, the actual point is m2. The compensation transforms m0 directly to m2, bypassing m1. Using homogeneous transformation matrices from robotics kinematics, we can derive the required adjustment.

Let the bending occur around an axis perpendicular to the sheet plane, with the bend line as the pivot. The transformation from m0 to m1 involves a rotation of α/2 (since the sheet symmetrically bends) and a translation along the sheet length. Accounting for elongation Δl, the combined transformation matrix T from m0 to m2 is:

$$T = \begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & \cos(\alpha/2) & -\sin(\alpha/2) & \pi t (1 – K) \cos(\alpha/2) \\

0 & \sin(\alpha/2) & \cos(\alpha/2) & \pi t (1 – K) \sin(\alpha/2) + n \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}$$

Here, t represents a normalized thickness factor (t = h / h_ref), and n is an offset distance from the bend line to the gripping point. This matrix is applied in real-time by the robot controller, adjusting the end effector’s position and orientation during bending. The derivation assumes small strains and linear elasticity, valid for most sheet metal operations. For complex bends, such as multi-stage or asymmetric bends, the matrix can be extended using Denavit-Hartenberg parameters. The compensation algorithm is integrated into the PLC code, calculating T based on input parameters (α, h, K) from the CAD model of the part. This enables the end effector to maintain optimal grip without inducing parasitic forces.

The effectiveness of this multifunctional flexible end effector was evaluated in a production setting. A robotic bending cell was established, comprising a six-axis industrial robot, a CNC press brake, and the end effector. The system automated the entire process: part pickup from a feeder, positioning in the die, bending with follow-up, and placement onto a conveyor. For small electronic parts (e.g., brackets, enclosures), the average bending time per part decreased from 0.1 hours manually to 0.02 hours with the end effector. For larger parts (e.g., chassis panels), time reduced from 0.2 to 0.04 hours. Setup time was slashed due to the end effector’s quick-adjust features; trial bends dropped from 4-6 parts to just 1. The mold cleaning function, activated every 50 cycles, prevented oxide buildup, eliminating manual die maintenance and improving consistency.

To validate the pose compensation, a sample of 1000 parts from various materials was processed. The table below compares rejection rates before and after implementing compensation, categorized by bend angle and thickness:

| Bend Angle α | Sheet Thickness h (mm) | Rejection Rate without Compensation (%) | Rejection Rate with Compensation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30° | 1.0 | 12.5 | 2.1 |

| 60° | 1.5 | 18.3 | 3.4 |

| 90° | 2.0 | 25.7 | 4.8 |

| 120° | 1.2 | 15.9 | 2.9 |

The data clearly shows that compensation significantly reduces rejects, especially for sharper bends and thicker materials. This underscores the importance of integrating deformation analytics into end effector control. Moreover, the flexible end effector demonstrated robustness across 50+ different part designs, from simple L-bends to complex U-profiles, without hardware changes. Operators simply input new parameters via the HMI, and the end effector auto-configures in under 30 seconds. This agility is paramount in electronics manufacturing, where product lifecycles are short and batch sizes vary widely.

Beyond immediate productivity gains, this end effector design opens avenues for further innovation. For instance, the adjustable drag chains could be motorized with servo drives for finer resolution, enabling handling of micro-parts. The cleaning head might incorporate ultrasonic vibration for more effective debris removal. From a control perspective, machine learning algorithms could be layered onto the PLC to predict deformation based on historical data, refining the compensation matrix in real-time. Such advancements would enhance the end effector’s intelligence, making it a core component of smart factories. Additionally, the end effector’s modularity allows integration with other tools, such as vision systems for inspection or laser markers for tracing, expanding its role beyond bending.

In conclusion, the multifunctional flexible end effector presented here addresses critical gaps in electronic sheet metal bending automation. Its design merges mechanical adaptability with intelligent control, solving issues of part diversity, oxide contamination, and deformation-induced inaccuracies. The pose compensation algorithm, rooted in solid mechanics, ensures high precision even for challenging geometries. As industries move toward greater customization and faster changeovers, such flexible automation tools become indispensable. This end effector not only boosts efficiency but also elevates quality standards, demonstrating how targeted engineering can transform traditional processes. Future work will focus on miniaturization for micro-electronics and cloud connectivity for predictive maintenance, further solidifying the end effector’s role in next-generation manufacturing.

Throughout this exploration, the term “end effector” has been emphasized to highlight its centrality in robotic systems. From structural adjustments to algorithmic compensations, every aspect of this device is geared toward enhancing flexibility and performance. As automation evolves, the lessons learned from this end effector can inform broader developments in robotic manipulation, particularly for delicate, high-mix production environments. The integration of formulas, tables, and practical insights aims to provide a comprehensive resource for engineers and researchers alike, fostering innovation in the field of robotic end effectors for sheet metal processing.