In recent years, robotic technology has been widely applied in various fields such as service and industry, and is gradually emerging in the medical domain. With the continuous advancement of robotics, bronchoscopic robots have become a hot research topic in healthcare. Traditional transrespiratory biopsy for pulmonary nodule diagnosis faces challenges like infection risks and manual operational limitations, prompting a trend toward integrating engineering with medicine for diagnosis and treatment. To achieve flexible movement, precise positioning, and stable intervention of flexible bodies in the complex, curved, and dynamic environment of bronchial lumens, we adopt a master-slave collaborative remote control robotic mechanism design. This simulates the operational habits of physicians in conventional surgery, enabling dual-instrument cooperative control for minimally invasive diagnosis and treatment via the bronchus. This paper focuses on the design of a transbronchial diagnostic robot and an in-depth analysis of the pose of its flexible end effector, providing a theoretical foundation for multi-instrument collaborative control in natural orifice biopsy procedures.

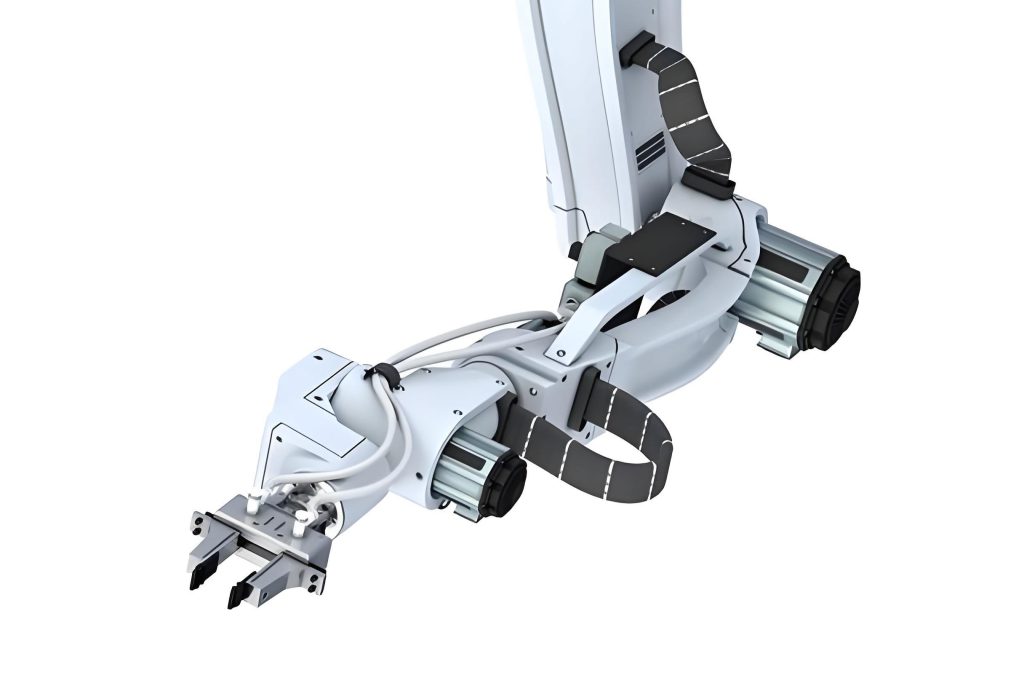

We designed an integrated mechanism prototype capable of simultaneously manipulating a bronchoscope and biopsy forceps. The flexible end effector of the robot resembles a concentric tube structure, comprising a bronchoscope flexible catheter with a biopsy channel. Based on the specifications of bronchoscope-assisted lung examination surgery, we analyzed the functions of the bronchoscope and biopsy forceps, deriving the basic execution methods and required strokes for the robot. The flexible end effector must accommodate multiple degrees of freedom, including axial movement, radial rotation, and cable-driven bending for the bronchoscope, as well as delivery, withdrawal, opening, and closing for the biopsy forceps. To realize these motions, we developed a robotic mechanism with corresponding joint transformations, and using the D-H method, we established its kinematic model. The homogeneous transformation matrix from the base coordinate system to the flexible end effector coordinate system is derived as follows:

$$ T^0_5 = T^0_1 T^1_2 T^2_3 T^3_4 T^4_5 = \begin{bmatrix} \cos^2\alpha_0 + \cos\beta_0 \sin^2\alpha_0 & \cos\alpha_0 \sin\alpha_0 (\cos\beta_0 – 1) & \sin\alpha_0 \sin\beta_0 & \frac{l_0}{\beta_0} \sin\alpha_0 (1 – \cos\beta_0) \\ \cos\alpha_0 \sin\alpha_0 (\cos\beta_0 – 1) & \cos\beta_0 \cos^2\alpha_0 + \sin^2\alpha_0 & \cos\alpha_0 \sin\beta_0 & \frac{l_0}{\beta_0} \cos\alpha_0 (1 – \cos\beta_0) \\ -\sin\alpha_0 \sin\beta_0 & -\cos\alpha_0 \sin\beta_0 & \cos\beta_0 & L_0 + \frac{l_0}{\beta_0} \sin\beta_0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

From this, the position coordinates \((X_T, Y_T, Z_T)\) of the flexible end effector are obtained:

$$ X_T = \frac{l_0}{\beta_0} \sin\alpha_0 (1 – \cos\beta_0) $$

$$ Y_T = \frac{l_0}{\beta_0} \cos\alpha_0 (1 – \cos\beta_0) $$

$$ Z_T = L_0 + \frac{l_0}{\beta_0} \sin\beta_0 $$

Here, \(L_0\) represents the axial advancement displacement, \(l_0\) is the active deflection length, \(\alpha_0\) is the radial rotation angle, and \(\beta_0\) is the deflection angle of the flexible end effector. This kinematic analysis confirms that the mechanism meets the basic motion requirements for transbronchial diagnostic procedures.

The overall system framework of the transbronchial diagnostic robot includes the diagnostic robot (comprising the main body mechanism, trolley, passive holding manipulator, and control hardware), a mobile master controller, and a navigation system (electromagnetic navigation positioning and visual navigation systems). The system operates on a master-slave collaborative basis: the master controller, developed using Python software on a Microsoft Surface Pro tablet, sends motion commands to the slave embedded controller, which then drives the robotic mechanism. Real-time bronchial lumen images are displayed via the visual navigation system (bronchoscope end camera), while the electromagnetic navigation system tracks the position and orientation of electromagnetic sensors. For component selection, we considered loads during operation to choose drive motors and配套硬件. The table below summarizes the functional analysis of the robot’s flexible end effector.

| End Effector | Function | Degrees of Freedom | Execution Method | Stroke |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronchoscope | Vision, Navigation | 3 | Axial Movement, Radial Rotation, Cable-driven Bending | Axial: (600 ± 25) mm, Rotation: ±180°, Bending: -130° to 160° |

| Biopsy Forceps | Grasping Pathological Samples | 2 | Delivery/Withdrawal, Opening/Closing, Passive Coiling | Delivery: ≤ 2300 mm, Opening: 0–15 mm, Coiling: 6.5 × 360° |

To analyze the pose of the flexible end effector in nonlinear resistance environments within bronchial lumens, we employed the Cosserat rod theory, a continuum mechanics theory for studying deformations of slender objects. The flexible end effector, modeled as an elastic rod, exhibits highly nonlinear characteristics under external loads due to spatial deformation. Based on the constitutive equations in Cosserat rod theory, we derived the动力学 equations by balancing linear and angular momentum for each cross-section. The linear momentum balance equation is:

$$ \rho A \cdot \partial^2_t \bar{r} = \partial_S (Q^T S \sigma^e) + e\bar{f} $$

And the angular momentum balance equation is:

$$ \rho I^e \cdot \partial_S \omega = \partial_S (B \kappa^e_3) + \kappa \times B \kappa^e_3 + (Q \bar{r}^e_S \times S \sigma) + (\rho I \cdot \omega^e) \times \omega + \rho I \omega^e_2 \cdot \partial_t e + eC $$

In these equations, \(\rho\) is density, \(A\) is cross-sectional area, \(\bar{r}\) and \(\bar{r}_S\) are local vectors, \(Q\) is the rotation matrix, \(S\) is the shear stiffness matrix, \(\sigma\) is the shear displacement vector, \(e\) is the local stretch ratio, \(I\) is the second moment of inertia, \(\omega\) is the angular velocity vector, \(B\) is the bending stiffness matrix, \(\kappa\) is the curvature vector, \(\bar{f}\) is external force, and \(C\) is coupled line density. For an elastic rod, \(B\) and \(S\) are 3×3 diagonal matrices defined as:

$$ B = \begin{bmatrix} EI_1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & EI_2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & GI_3 \end{bmatrix}, \quad S = \begin{bmatrix} \alpha_c GA & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \alpha_c GA & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & EA \end{bmatrix} $$

where \(E\) is Young’s modulus, \(G\) is shear modulus, \(I_i\) (i=1,2,3) are second moments of area, and \(\alpha_c\) is a constant. The load-strain and torque-curvature relationships follow the constitutive laws:

$$ n = S (\sigma – \sigma_0) $$

$$ \tau = B (\kappa – \kappa_0) $$

with \(n\) as internal load, \(\tau\) as internal torque, and \(\sigma_0\), \(\kappa_0\) as reference values. These equations, combined with initial and boundary conditions, allow us to solve for the equilibrium pose of the flexible end effector numerically.

We conducted simulation studies using MATLAB software with the SoRoSim toolbox to investigate the energy conversion, force-position mapping relationship, and workspace of the flexible end effector. The simulation framework encompassed three main aspects: energy balance verification to validate elastic damping, force-position mapping to predict passive deformation under tissue forces, and workspace analysis to assess the feasibility of robotic functions. We modeled the flexible end effector as a cylindrical elastic rod with a length of 50 mm and diameter of 5.2 mm, simulating the bending section of the bronchoscope flexible catheter. In energy balance simulations, we applied driving forces to deflect the end effector to a maximum of 130° on one side, then released the force to observe energy conversion under gravity over 10 seconds. The results showed that with damping, the total energy decayed, while without damping, it remained constant, confirming the validity of damping parameters for subsequent analyses.

For force-position mapping simulations, we applied linearly increasing forces up to 0.2 N to the end effector under various deflection angles (0°, upward 30°, upward 60°, downward 30°, downward 60° in the vertical plane, and 0°, unilateral 30°, unilateral 60° in the horizontal plane). The simulations used a Young’s modulus of 19 GPa and a quartic bending strain mode around the Y-axis. The force-position relationships indicated that in vertical deflections, the deformation varied linearly with force for 0°, upward 30°, and upward 60°, while for downward deflections, deformation increased significantly with force. In horizontal deflections, the curves showed similar trends, with deformation growing gradually as force approached 0.2 N. The table below summarizes key simulation outcomes for the flexible end effector’s force-position mapping.

| Deflection Condition | Force Range (N) | Deformation Range (mm) | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical 0° | 0–0.2 | 0–1.2 | Linear relationship |

| Vertical Upward 30° | 0–0.2 | 0–1.5 | Linear relationship |

| Vertical Upward 60° | 0–0.2 | 0–1.8 | Linear relationship |

| Vertical Downward 30° | 0–0.2 | 0–2.5 | Force increases rapidly then slowly |

| Vertical Downward 60° | 0–0.2 | 0–3.0 | Force increases rapidly then slowly |

| Horizontal 0° | 0–0.2 | 0–1.1 | Deformation increases slowly then quickly |

| Horizontal Unilateral 30° | 0–0.2 | 0–1.3 | Similar trend to horizontal 0° |

| Horizontal Unilateral 60° | 0–0.2 | 0–1.4 | Similar trend to horizontal 0° |

These results predict that within a safe force range below 0.2 N, the flexible end effector can produce elastic deformations exceeding 1.1 mm, allowing for passive following and protecting the bronchial wall from scratches. Pre-bending the bronchoscope flexible end effector before contact can further reduce risks.

Workspace simulations involved simplifying the flexible end effector as a slender continuum fixed at one end with drives for axial movement, radial rotation, and cable-driven bending. Over 6 and 12 seconds, we simulated helical advancement motions and used Monte Carlo sampling to generate a point cloud of the end effector’s positions. The workspace appeared as a regular egg shape, influenced by the combined motions. The distribution probability of points decreased from top to bottom due to asymmetric bending limits (-130° to +160°) and increased resistance at larger deflection angles. The mathematical representation of the workspace can be derived from the kinematic equations, with the probability density function approximated as:

$$ P(x,y,z) \propto \exp\left(-\frac{(z – z_0)^2}{2\sigma_z^2}\right) $$

where \(z_0\) is the mean axial position and \(\sigma_z\) is the standard deviation, reflecting the decreasing density along the Z-axis. This analysis confirms that the flexible end effector can access up to level 3–4 bronchial lumens, supporting its feasibility for full-lung reach in diagnostic procedures.

We performed experimental validations to assess the real-world performance of the transbronchial diagnostic robot. The physical robot includes an NVIDIA embedded controller,适配 drivers, terminal blocks, power modules, and mechanisms for biopsy forceps operation, bronchoscope movement, and end effector bending. Experiments focused on force-position mapping tests, workspace calibration, and robotic performance verification. For force-position mapping, we fixed the bronchoscope flexible catheter as a cantilever beam with a free length of 60 mm and applied pressure using a press at 40 mm from the fixed point. The press exerted forces up to 0.2 N at 3 mm/min, with a jump threshold of 0.01 N, while a six-axis S-type force sensor recorded data. The end effector was tested under vertical and horizontal deflections, similar to simulations. Experimental results aligned with simulations, showing deformations over 1.1 mm under forces below 0.2 N, validating the safety of the flexible end effector. The table below compares experimental deformation ranges with simulation predictions.

| Deflection Condition | Experimental Deformation (mm) | Simulation Deformation (mm) | Deviation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical 0° | 1.1–1.3 | 1.0–1.2 | ≤0.1 |

| Vertical Upward 30° | 1.4–1.6 | 1.3–1.5 | ≤0.1 |

| Vertical Upward 60° | 1.7–1.9 | 1.6–1.8 | ≤0.1 |

| Vertical Downward 30° | 2.3–2.6 | 2.2–2.5 | ≤0.1 |

| Vertical Downward 60° | 2.8–3.1 | 2.7–3.0 | ≤0.1 |

| Horizontal 0° | 1.0–1.2 | 0.9–1.1 | ≤0.1 |

| Horizontal Unilateral 30° | 1.2–1.4 | 1.1–1.3 | ≤0.1 |

| Horizontal Unilateral 60° | 1.3–1.5 | 1.2–1.4 | ≤0.1 |

For workspace calibration, we attached electromagnetic sensors to the bronchoscope exterior using tape and employed an Aurora electromagnetic tracking system from NDI. The sensors tracked the pose of the flexible end effector as it navigated through a human model’s respiratory tract to level 3–4 bronchial lumens. Depth cameras also captured data, and poses were reconstructed in a transparent model. Results demonstrated that the end effector could achieve full-lung access, corroborating simulation-based workspace predictions. The calibration process involved solving the inverse kinematics to map sensor data to the robot’s joint angles, expressed as:

$$ \theta = f^{-1}(X, Y, Z, \alpha, \beta) $$

where \(\theta\) represents joint angles, and \(f\) is the forward kinematics function derived earlier.

Robotic performance verification was conducted on an animal platform using a Bama pig under deep anesthesia. We tested radial rotation and axial movement performance by commanding the end effector to perform reciprocal motions (0° to 180° rotation and reciprocating advancement over 210 mm). A rotary encoder and displacement sensor recorded real-time data, compared with commands from the master controller. The results showed slight hysteresis due to communication delays but high precision in following and positioning. The radial rotation error ranged from -0.472° to 0.365°, and axial movement error from -0.06 to 0.06 mm. The performance metrics are summarized below.

| Motion Type | Test Duration | Stroke | Error Range | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Rotation | 40 s | 180° | -0.472° to 0.365° | Stable operation, slight delay |

| Axial Movement | 30 s | 210 mm | -0.06 to 0.06 mm | Smooth motion, high precision |

The force-position mapping and workspace analyses emphasize the importance of the flexible end effector’s adaptability in constrained environments. By leveraging Cosserat rod theory, we can model the end effector’s behavior under external loads, ensuring safe interaction with bronchial tissues. The end effector’s design allows for passive deformation upon contact, reducing the risk of damage. In master-slave control, although delays exist, they are negligible in slow, precise operations typical of surgical settings. The dual-instrument coordination enables simultaneous bronchoscope navigation and biopsy forceps manipulation, enhancing diagnostic efficiency.

In conclusion, we designed a transbronchial diagnostic robot with a flexible end effector and investigated its pose under dual-instrument cooperative control. Based on Cosserat rod theory, we established a mechanical model for the end effector and conducted simulations using MATLAB’s SoRoSim toolbox to solve force-position relationships, poses, and workspace. Experimental tests validated the end effector’s pose and robotic performance. Key findings include: (1) The flexible end effector, as a flexible continuum structure, exhibits微小 passive deformations under bronchial wall tissue forces, with force-position mapping guiding safe operation. (2) Master-slave remote operation involves control delays, but following errors are minimal in practical slow-motion scenarios, allowing real-time pose adjustment of the end effector. This research provides a theoretical foundation for multi-instrument协同 control in natural orifice biopsy, particularly highlighting the role of the end effector in ensuring precision and safety. Future work could focus on enhancing the end effector’s stiffness modulation, integrating AI for autonomous navigation, and expanding clinical trials to validate robustness in diverse anatomical structures.

The flexible end effector’s performance is critical to the success of transbronchial procedures. Through continuous refinement of its design and control algorithms, we aim to improve the end effector’s dexterity and reliability. The integration of real-time feedback from electromagnetic and visual systems will further optimize the end effector’s positioning accuracy. As robotic technology evolves, the end effector will play a pivotal role in advancing minimally invasive diagnostic techniques, ultimately benefiting patient outcomes. The end effector’s ability to conform to complex bronchial geometries while maintaining stability underscores its value in medical robotics. We anticipate that ongoing research on the end effector will lead to innovations in soft robotics and surgical automation, paving the way for more sophisticated diagnostic tools.