The pursuit of efficient, reliable, and high-load capacity linear motion solutions has driven the evolution of various mechanical components. Among these, the planetary roller screw stands as a sophisticated alternative to the ubiquitous ball screw. While offering distinct advantages in specific scenarios, its adoption has been tempered by significant engineering challenges. This article provides a detailed examination of the planetary roller screw mechanism, comparing its fundamental principles, performance characteristics, and practical limitations against the established ball screw, with a focus on critical design and reliability factors.

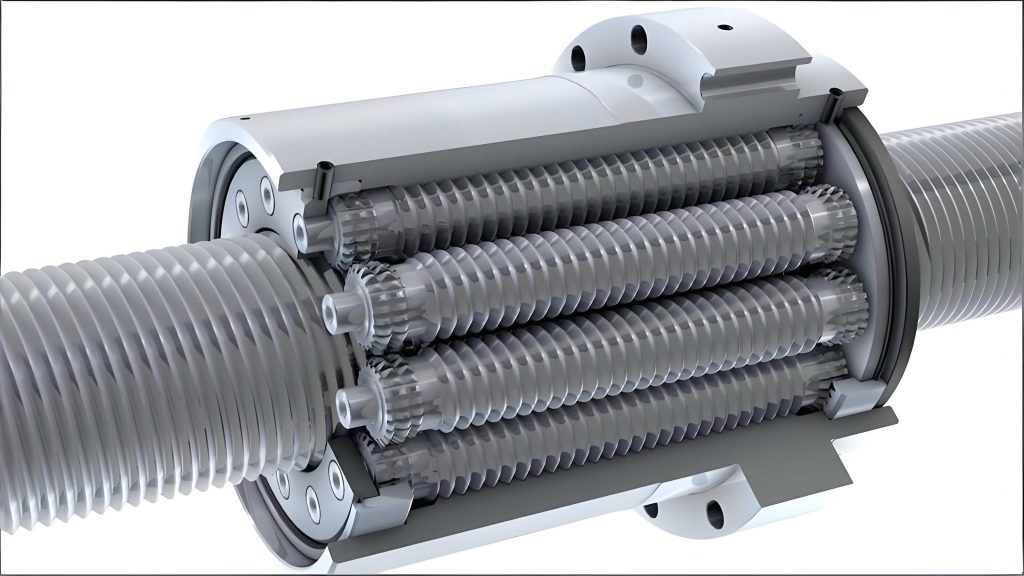

Invented in 1942 by Carl Bruno Strandgren, the planetary roller screw mechanism remained a niche technology for decades due to its manufacturing complexity. It was not until the late 20th century that specialized companies began its systematic development and production. The core structure of a planetary roller screw assembly consists of several key components: a threaded screw shaft, a threaded nut, multiple threaded rollers, an internal gear ring (or retainer), and necessary end caps or retaining rings. The screw and nut typically feature a multi-start thread with a 90-degree included angle profile, while the rollers have a single-start thread with a double-convex arc profile. These rollers are distributed evenly around the screw, housed within the nut.

The fundamental operating principle mimics planetary gear systems. When the screw rotates, the rollers are driven, causing them to both revolve around the screw axis (planetary motion) and rotate on their own axes. This combined rolling motion translates the rotational input of the screw into precise linear movement of the nut. The contact between the screw, rollers, and nut is theoretically a rolling contact, which can yield high mechanical efficiency, potentially up to 90%. The internal gear ring engages with teeth on the ends of the rollers, synchronizing their movement and preventing skewing or tilting that could lead to jamming or premature wear. The load in a planetary roller screw is primarily carried through point contacts on the flanks of the 90-degree thread profiles.

The kinematic relationship governing the linear travel per revolution (lead, \( L \)) of a standard planetary roller screw is given by:

$$ L = P_h \cdot \frac{Z_s}{Z_r} $$

Where \( P_h \) is the thread pitch of the roller, \( Z_s \) is the number of starts on the screw, and \( Z_r \) is the number of starts on the roller (typically 1). For a reversing planetary roller screw design, where the rollers have threads opposing those on the screw and nut, the lead is simplified to \( L = P_h \). The contact mechanics are complex. The normal load \( Q \) at each contact point between the roller and the screw or nut generates contact stresses. For the point contact between the convex roller thread and the flat screw/nut flank, a simplified approach using Hertzian contact theory can be applied. The maximum contact pressure \( p_{max} \) can be estimated, though the actual condition involves multiple, statically indeterminate contact points.

| Feature | Ball Screw Assembly | Planetary Roller Screw Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Composition | Screw, nut, ball bearings, return tube/circuit. Simple structure. | Screw, nut, threaded rollers, internal gear ring, end caps. Complex structure. |

| Recirculation Mechanism | Balls circulate via return tubes or internal deflectors, forming one or more independent ball circuits. | Rollers perform planetary motion within the nut. No discrete recirculation path; continuous rolling contact. |

| Rolling Element | Ball bearings. | Cylindrical, threaded rollers. |

| Form Factor & Size | Nut housing is relatively compact as balls are recessed into deep groove profiles. | Nut housing is generally larger due to the roller diameter and the need to house the planetary mechanism. |

| Motion Smoothness & Noise | Potential for slight impact/vibration as balls pass through the return system, especially at high speeds. | Generally smoother and quieter operation due to absence of recirculating impact points. |

| Theoretical Contact Points | Typically two points of contact per ball in a loaded groove (for Gothic arch profile). | Multiple contact points per roller (2 per thread flank under ideal preload, per engaged thread). More load-sharing threads. |

| Manufacturing & Assembly | Well-established, relatively simpler processes. High consistency achievable. | Extremely complex machining of multi-start threads and roller profiles. Stringent assembly tolerances required. |

| Inherent Reliability | High, due to simple geometry, proven design, and predictable fatigue life of ball bearings. | Potentially compromised by complexity, sensitivity to machining errors, and challenging preload management. |

While the planetary roller screw boasts a higher theoretical load capacity, especially for small diameters and leads, due to a greater number of contact points, its practical, achievable load rating is often significantly lower than theoretical predictions. This gap is attributable to several critical and cumulative manufacturing and assembly challenges:

- Contact Point Integrity and Preload: Achieving perfect, simultaneous contact on all four flanks (two on the screw, two on the nut) for every thread of every roller is virtually impossible. Slight variations in roller pitch diameter, thread profile, and lead errors mean the load is carried by a subset of the theoretical contacts. Incorrect preload can lead to uneven load distribution, drastically reducing capacity and life.

- Thread Profile and Half-Angle Errors: The 90-degree thread profile and its precise half-angle (45°) are critical. Deviations during machining cause mismatched contact, shifting the load point and concentrating stress. This also creates asymmetry between forward and reverse loading.

- Multi-Start Thread Indexing Error: Both the screw and nut have multi-start threads. Any error in the angular indexing (phase) between these starts means that not all thread starts engage the rollers equally. The actual load is carried only by the few starts that are properly aligned, a fact often visible in product photographs where only portions of the threads show wear.

- Roller Profile Accuracy: The double-convex arc profile of the roller thread must be machined with extreme precision regarding its radius and the location of its center. Errors here prevent optimal rolling and increase sliding friction, reducing efficiency and creating localized stress points.

- Roller End Gear/Synchronization Mesh: The engagement between the roller end gears and the internal ring gear is crucial for maintaining roller alignment. Excessive backlash or poor meshing allows rollers to skew, leading to edge loading, increased friction, and potential catastrophic thread damage.

- Lead Accuracy Consistency: The lead accuracy of the screw, nut, and all rollers must be exceptionally consistent. Lead mismatches prevent uniform load sharing across the length of engagement, causing end threads to carry disproportionate loads.

- Straightness and Alignment: Bending or lack of straightness in the screw or rollers prevents uniform contact along their entire length. This effectively reduces the active engaged length, lowering the overall load capacity.

The combined effect of these factors makes the planetary roller screw a mechanism with inherently lower design margin and reliability compared to its ball screw counterpart. This complexity is the primary reason for its limited proliferation despite its theoretical advantages. The static load capacity \( C_{0a} \) and dynamic load capacity \( C_a \) for a planetary roller screw are highly sensitive to these manufacturing imperfections. A de-rating factor \( K_{rel} \) (where \( K_{rel} < 1 \)) could conceptually be applied to theoretical formulas to reflect real-world reliability:

$$ C_{a\text{ (actual)}} = K_{rel} \cdot C_{a\text{ (theoretical)}} $$

Conversely, ball screw technology has seen continuous advancement. Manufacturers have developed “high-capacity” or “heavy-duty” ball screw designs that narrow or even surpass the load gap. These designs employ larger ball diameters, increased circuit count, optimized contact angles, and improved load distribution. The fundamental simplicity of the ball screw—relying on highly spherical, standardized balls rolling in well-defined grooves—makes achieving high and consistent load ratings more reliable. The basic dynamic load rating formula for a ball screw highlights the benefit of larger, more numerous balls:

$$ C_a = f_c \cdot (i \cdot l_a \cdot \sin \alpha)^{2/3} \cdot Z^{2/3} \cdot D_w^{1.8} $$

Where \( f_c \) is a factor depending on geometry and material, \( i \) is the number of loaded circuits, \( l_a \) is the number of turns per circuit, \( \alpha \) is the contact angle, \( Z \) is the number of balls per turn, and \( D_w \) is the ball diameter. Advances in these parameters have significantly boosted ball screw performance. The following table provides a comparative snapshot of load ratings for similarly sized components, illustrating that while the planetary roller screw holds an advantage in some small-form-factor cases, the gap is not absolute, and ball screws offer competitive or superior capacity in many ranges, with likely higher reliability.

| Specification (Diameter x Lead) | Component Type / Source | Nut OD (approx. mm) | Dynamic Load Rating, \( C_a \) (kN) | Static Load Rating, \( C_{0a} \) (kN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32×10 mm | Ball Screw (Manufacturer A) | 58 | 102.9 | 191.3 |

| 32×10 mm | Ball Screw (Manufacturer B) | 58 | 71 | 169 |

| 30×10 mm | Planetary Roller Screw (Manufacturer C) | 64 | 101 | 174 |

| 40×10 mm | Ball Screw (Manufacturer A) | 66 | 162.6 | 336 |

| 40×10 mm | Planetary Roller Screw (Manufacturer D) | 80 | 124.4 | 247.4 |

| 63×16 mm | Ball Screw (Manufacturer A) | 105 | 577.1 | 1461.3 |

| 64×18 mm | Planetary Roller Screw (Manufacturer D) | 115 | 238.1 | 612.3 |

The application of planetary roller screw mechanisms in critical fields like aerospace and aviation demands paramount reliability due to the non-serviceable nature of many systems in flight. The historical development path is telling: the ball screw, with its simpler design and more robust performance envelope, saw rapid adoption and evolution across industries, including aerospace. The planetary roller screw, constrained by its complexity, remained specialized. While it may be suitable for certain ground-based, high-load, low-speed applications where its smooth motion is beneficial and maintenance is possible, its use in flight-critical aerospace systems introduces risk. The failure modes associated with thread indexing errors, roller synchronization issues, and sensitive preload are difficult to fully mitigate and qualify for the extreme reliability standards required.

In conclusion, the planetary roller screw is an ingenious mechanism with notable advantages in specific niches, such as smooth motion and potentially high load density in compact spaces. However, its structural and manufacturing complexity directly challenges its reliability and consistent performance. The ball screw, through decades of refinement and innovation in materials, precision manufacturing, and design (like high-capacity variants), offers a compelling combination of high performance, proven reliability, and economic viability. For engineers, the selection process must go beyond theoretical load tables and carefully weigh the practical limitations and lifecycle reliability of the planetary roller screw against the mature and dependable solutions provided by advanced ball screw technology, especially in mission-critical applications. The future development of the planetary roller screw hinges on breakthroughs in cost-effective, ultra-precision manufacturing and assembly techniques that can reliably realize its theoretical potential.