The precise measurement of single-root tensile strength is a critical parameter in evaluating soil stability and reinforcing mechanisms. Given the significant variability in the mechanical properties of roots across different plant species and diameters, conducting reliable tensile tests is essential. In conventional testing, universal testing machines with standard clamps are often employed. However, these clamps typically lack integrated force sensors, making it difficult to estimate and control the clamping force accurately. This limitation frequently leads to root slippage or, more critically, damage at the clamping point, resulting in premature test failure and unreliable data. While some researchers have attempted to mitigate this issue by modifying clamping methods—such as removing the root epidermis and injecting epoxy resin for fixation or using hook-and-loop fasteners to increase friction—these approaches are often species-specific, time-consuming, and may alter the root’s natural mechanical state. Consequently, there is a pressing need for an end effector capable of stable, precise, and adaptive force control to ensure the integrity of the root sample during testing.

Compliant grasping strategies, inspired by soft robotics, offer a promising direction for minimizing damage to delicate objects. Researchers have developed various force-feedback and slip-detection mechanisms for agricultural harvesting end effectors, significantly reducing fruit damage. These methods often rely on direct force/torque measurements or complex contact models. However, a common assumption in these strategies is a constant or known environmental stiffness (e.g., of the fruit). In the context of root testing, the effective “environmental stiffness” experienced by the end effector is highly variable, depending on the root’s diameter, species, hydration, and the specific contact mechanics at the clamp interface. Ignoring this variability can lead to improper force regulation, causing either insufficient grip or excessive crushing force.

Accurate estimation of the interaction force between the end effector and the root is a prerequisite for any advanced control scheme. Integrating high-precision force/torque sensors directly into a compact clamping mechanism is challenging due to cost, space constraints, and potential bandwidth limitations that could affect system stability. Therefore, sensorless force estimation techniques, which deduce interaction forces from readily available motor states like current, position, and velocity, are highly advantageous. Methods range from model-based observers, like generalized momentum observers (GMOs), to data-driven approaches like neural networks. Furthermore, to achieve truly adaptive control, the system must be able to identify or estimate key environmental parameters, such as the contact stiffness, in real-time.

To address these interconnected challenges—precise force control without direct sensing, and adaptability to unknown environmental stiffness—this work proposes a comprehensive solution. We first present the mechanical design of a specialized end effector for root tensile testing. We then develop a sensorless adaptive admittance control framework. This framework consists of three core components: (1) an Adaptive Sliding Mode Generalized Momentum Observer (ASMGMO) for real-time estimation of the root-end effector interaction force without physical sensors; (2) a hybrid Simulated Annealing Particle Swarm Optimization-based Recursive Least Squares (SAPSO-RLS) algorithm for online identification of the environmental stiffness parameter; and (3) an admittance controller whose parameters (stiffness and damping) are dynamically adjusted based on the estimated force and identified environment. The integrated system allows the end effector to achieve rapid, stable, and accurate clamping force regulation, minimizing root damage. The performance of the proposed method is validated through detailed simulation models and comparative analysis with fixed-parameter and partially adaptive control strategies.

End Effector System Design and Modeling

Mechanical Design of the End Effector

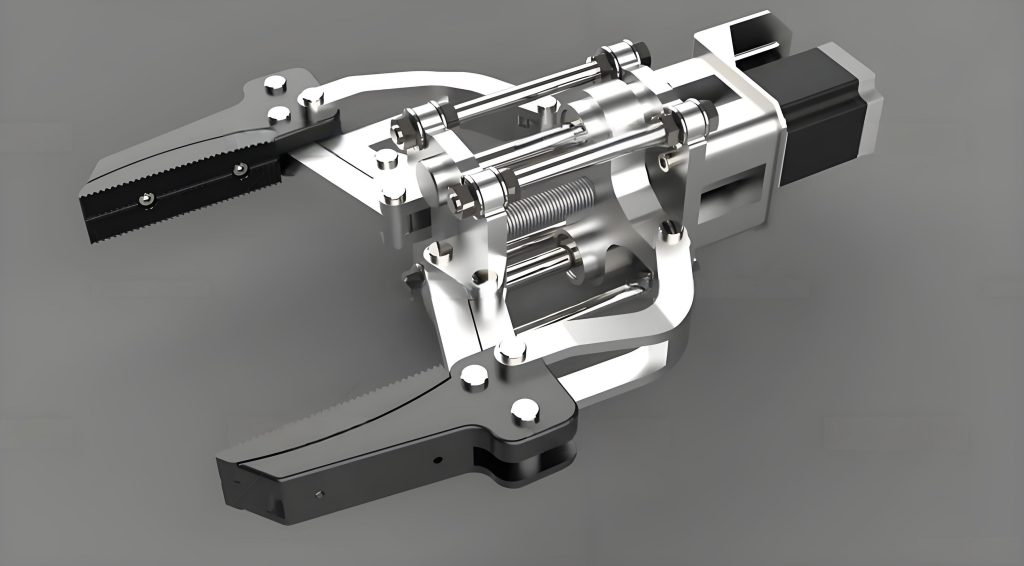

The designed end effector aims to provide a stable, damage-minimizing grip on plant roots of varying diameters and textures. Its architecture is divided into three main subsystems: a replaceable gripping module, a drive and actuation mechanism, and an embedded estimation and control system. The gripping module features a multi-degree-of-freedom structure that can be swapped to accommodate different root physical characteristics. The contact surfaces of the gripper jaws are convex to maximize the contact area with the root, thereby distributing pressure and enhancing frictional forces. This design reduces stress concentration, which is a primary cause of root crushing.

The actuation mechanism employs a horizontal layout to eliminate gravitational effects on the clamping force. It is comprised of a DC servo motor, a coupling, and a ball screw drive assembly. The rotary motion of the motor is converted into linear motion of the slider, which houses the gripping module. The overall three-dimensional model illustrates a compact and functional design suitable for integration into a tensile testing apparatus.

Mathematical Modeling of the End Effector System

To formulate the control strategy, a precise mathematical model of the end effector dynamics is essential. The model is derived from the electromechanical equations governing the servo motor and the mechanical transmission to the gripping jaws.

Actuator Dynamics: The torque balance equation for the motor is given by:

$$K_t i_m – \tau_l = J_{eq} \ddot{\theta}_m + B_{eq} \dot{\theta}_m$$

where:

- $K_t$ is the motor torque constant (N·m/A),

- $i_m$ is the armature current (A),

- $\tau_l$ is the load torque (N·m),

- $J_{eq}$ is the equivalent moment of inertia at the motor shaft (kg·m²),

- $B_{eq}$ is the equivalent viscous damping coefficient (N·m·s/rad),

- $\theta_m$ is the motor angular position (rad).

The electrical equation for the armature circuit (neglecting inductance) is:

$$u_c = R_a i_m + K_b \dot{\theta}_m$$

where $u_c$ is the control voltage (V), $R_a$ is the armature resistance (Ω), and $K_b$ is the back EMF constant (V·s/rad).

Combining these equations to eliminate $i_m$ yields:

$$K_t \left( \frac{u_c – K_b \dot{\theta}_m}{R_a} \right) – \tau_l = J_{eq} \ddot{\theta}_m + B_{eq} \dot{\theta}_m$$

Kinematic Transformation: The linear displacement $x$ of the gripper jaw is related to the motor rotation through the gear reduction ratio $n$ and the ball screw lead $p$:

$$x = \frac{\theta_m}{n} \cdot \frac{p}{2\pi}$$

Defining a conversion factor $M_e = \frac{2\pi n}{p}$, we have $\dot{\theta}_m = M_e \dot{x}$ and $\ddot{\theta}_m = M_e \ddot{x}$. For control design, the load torque $\tau_l$ is considered part of the external interaction. Substituting the kinematic relations and simplifying, we obtain the dynamic equation in the linear displacement domain:

$$\frac{K_t}{R_a} u_c = J_{eq} M_e \ddot{x} + \left(B_{eq} M_e + \frac{K_t K_b}{R_a} M_e \right) \dot{x} + \tau_l M_e^{-1}$$

For controller formulation, this is often expressed in a standard second-order form relevant to the end effector:

$$M \ddot{x} + B \dot{x} = u – F_{ext}$$

where $M$ and $B$ are the effective mass and damping coefficients of the end effector system, $u$ is the control input (related to $u_c$), and $F_{ext}$ is the external force from the root, which opposes the clamping motion.

Environment and Admittance Control Model

The interaction between the end effector and the root is modeled. Given the relatively low velocities and accelerations during the clamping phase, a simple linear spring model is often sufficient for control design:

$$F_e = \begin{cases}

K_e (x – x_e), & x \ge x_e \\

0, & x < x_e

\end{cases}$$

where $F_e$ is the interaction (clamping) force, $K_e$ is the unknown environment stiffness (N/m), $x$ is the jaw position, and $x_e$ is the position where contact is first established.

Admittance control is a well-established strategy for force regulation. It imposes a desired dynamic relationship between force error and position adjustment, creating a virtual “spring-mass-damper” behavior for the end effector. The standard second-order admittance model is:

$$M_d \Delta \ddot{x} + B_d \Delta \dot{x} + K_d \Delta x = \Delta F$$

where $\Delta x = x_r – x$ is the position modification, $x_r$ is the reference position from a trajectory planner, $\Delta F = F_d – F_e$ is the force error ($F_d$ is the desired force), and $M_d$, $B_d$, $K_d$ are the virtual inertia, damping, and stiffness parameters of the admittance controller, respectively. The Laplace transform yields the admittance transfer function:

$$\frac{\Delta X(s)}{\Delta F(s)} = \frac{1}{M_d s^2 + B_d s + K_d}$$

The output $\Delta x$ is added to the reference trajectory to generate a modified position command $x_c = x_r + \Delta x$ for the underlying position controller of the end effector. The stability and performance (overshoot, settling time) of the force response depend critically on the choice of $M_d$, $B_d$, and $K_d$. A fundamental result is that the steady-state force error is influenced by the ratio between the admittance stiffness $K_d$ and the environment stiffness $K_e$:

$$e_{ss} \propto \left( \frac{K_e}{K_d + K_e} \right) F_d$$

This highlights the necessity of adapting $K_d$ relative to the (unknown) $K_e$ to achieve zero steady-state error.

Proposed Adaptive Control Framework

The proposed control framework for the end effector seamlessly integrates sensorless force estimation, online environment parameter identification, and adaptive admittance law adjustment. The block diagram illustrates the information flow, culminating in precise clamping force control.

Sensorless Force Estimation via ASMGMO

To estimate the interaction force $F_e$ without a sensor, we design an Adaptive Sliding Mode Generalized Momentum Observer (ASMGMO). The generalized momentum $p = M \dot{x}$ is defined. From the dynamics $M \ddot{x} = u – B\dot{x} – F_e$, the derivative of momentum is $\dot{p} = u – B\dot{x} – F_e$.

We define a sliding surface $s = \hat{p} – p$, where $\hat{p}$ is the estimated momentum. The observer dynamics are proposed as:

$$\dot{\hat{p}} = u – B\dot{x} + K_l s + \xi_s$$

where $K_l$ is a linear gain, and $\xi_s$ is an adaptive sliding mode term designed for robustness and fast convergence:

$$\xi_s = -K_1 [s + K_3 \text{sig}(s)] – K_2 \int_0^t \left[ s + \frac{3}{2} K_3 s^{1/2} \text{sig}(s) \right] d\tau$$

Here, $\text{sig}(\cdot)$ is the signum function. The gains $K_1$, $K_2$, $K_3$ are adapted online using update laws derived from a Lyapunov stability analysis to ensure $s \to 0$:

$$\begin{aligned}

\dot{K}_1 &= \gamma_1 s (s + K_3 \text{sig}(s)) \\

\dot{K}_2 &= \gamma_2 s \int \left( s + \frac{3}{2} K_3 s^{1/2} \text{sig}(s) \right) d\tau \\

\dot{K}_3 &= \gamma_3 s \left( K_1 s \text{sig}(s) + K_2 \int \frac{3}{2} s^{1/2} \text{sig}(s) d\tau \right)

\end{aligned}$$

where $\gamma_1, \gamma_2, \gamma_3 > 0$ are adaptation rates. When the sliding surface is reached ($s \approx 0$), the force estimate $\hat{F}_e$ can be derived from the equivalent control principle of the sliding mode term, effectively given by:

$$\hat{F}_e \approx K_2 \int_0^t \left[ s + \frac{3}{2} K_3 s^{1/2} \text{sig}(s) \right] d\tau$$

This ASMGMO provides a continuous and smooth estimate of the clamping force for the end effector, robust to disturbances and parameter variations.

Online Environment Parameter Identification via SAPSO-RLS

To adapt the controller to the unknown root stiffness $K_e$, we propose a hybrid SAPSO-RLS identification algorithm. The environment interaction is modeled with a Kelvin-Voigt contact model for a more general representation during dynamics:

$$F_e = K_e x + B_e \dot{x}$$

where $B_e$ is an environmental damping coefficient. The parameter vector to be identified is $\theta = [K_e, B_e]^T$.

Offline Initialization with SAPSO: A combined Simulated Annealing Particle Swarm Optimization (SAPSO) method is used to find a good initial parameter estimate, especially when the search space is large due to the diversity of roots. SA provides a global search capability, while PSO refines the solution.

- Simulated Annealing (SA): Explores the parameter space widely. A new solution $\theta_{new}$ is accepted with probability $P = \min(1, \exp(-\Delta f / T))$, where $\Delta f$ is the change in a cost function (e.g., mean squared error between estimated and modeled force) and $T$ is a decreasing temperature parameter.

- Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): Uses the SA result as an initial swarm center. Particles update their velocity $v_i$ and position $\theta_i$:

$$v_i^{(k+1)} = \omega v_i^{(k)} + c_1 r_1 (pbest_i – \theta_i^{(k)}) + c_2 r_2 (gbest – \theta_i^{(k)})$$

$$\theta_i^{(k+1)} = \theta_i^{(k)} + v_i^{(k+1)}$$

where $\omega$ is an inertial weight, $c_1, c_2$ are learning factors, $r_1, r_2$ are random numbers, $pbest_i$ is the particle’s best position, and $gbest$ is the swarm’s best position.

The result $\hat{\theta}_{init}$ provides a robust starting point for the online estimator.

Online Tracking with RLS: Once initialized, a Recursive Least Squares (RLS) algorithm with forgetting factor performs real-time parameter updates. The model is $F_e(k) = \phi^T(k) \theta(k) + \epsilon(k)$, where $\phi(k) = [x(k), \dot{x}(k)]^T$. The RLS algorithm updates the estimate as follows:

$$\begin{aligned}

\hat{\theta}(k) &= \hat{\theta}(k-1) + L(k) [F_e(k) – \phi^T(k) \hat{\theta}(k-1)] \\

L(k) &= \frac{P(k-1) \phi(k)}{\lambda + \phi^T(k) P(k-1) \phi(k)} \\

P(k) &= \frac{1}{\lambda} [P(k-1) – L(k) \phi^T(k) P(k-1)]

\end{aligned}$$

where $L(k)$ is the update gain, $P(k)$ is the covariance matrix, and $0 < \lambda \le 1$ is the forgetting factor, giving more weight to recent data. This allows the end effector system to track slow changes in root compliance during clamping.

Target Position Update and Adaptive Admittance Law

With a reliable force estimate $\hat{F}_e$ and an identified environment stiffness $\hat{K}_e$, we can enhance the basic admittance control in two key ways.

1. Target Position Update: To achieve the desired force $F_d$ at steady state, the reference position $x_r$ must be compatible with the environment. Using the identified stiffness, the required position for a given force is $x_d = x_e + F_d / \hat{K}_e$. Since $x_e$ is unknown, we continuously update the target position based on the current state:

$$x_r(k+1) = x(k) + \frac{F_d – \hat{F}_e(k)}{\hat{K}_e(k)}$$

This effectively shifts the equilibrium point of the admittance system to where the desired force is achieved.

2. Adaptive Admittance Parameters: Fixed $K_d$ and $B_d$ may lead to slow response or large overshoot if mismatched to $K_e$. We propose the following adaptation laws:

- Admittance Stiffness ($K_d$): Adjusted to maintain a desired relationship with the estimated environment stiffness, promoting critical damping and zero steady-state error.

$$K_d(k) = \alpha \hat{K}_e(k) + \sigma_{\Delta F} |\Delta \hat{F}(k)|$$

where $\alpha$ is a positive ratio (e.g., 0.7), $\Delta \hat{F} = F_d – \hat{F}_e$, and $\sigma_{\Delta F}$ is a scaling factor that decreases as the force error diminishes. - Admittance Damping ($B_d$): Adjusted to ensure a well-damped response. It starts relatively high for rapid engagement and reduces as the system settles.

$$B_d(k) = \beta \sqrt{M_d \hat{K}_e(k)} + \sigma_{\Delta F} |\Delta \hat{F}(k)| + \frac{B_0}{1+t/\tau}$$

where $\beta$ is a damping ratio coefficient, and the last term provides initial high damping that decays over time constant $\tau$.

These adaptive laws ensure that the end effector‘s dynamic response is continuously optimized for the specific root being tested, enabling fast, stable, and accurate force tracking.

Simulation Results and Analysis

To validate the proposed framework, a comprehensive simulation model of the end effector system was built. The performance of the ASMGMO force observer, the SAPSO-RLS identifier, and the overall adaptive admittance controller (AAC) was evaluated and compared against two benchmarks: a fixed-parameter admittance controller (FAC) and a variable-stiffness-only adaptive controller (VAC).

Performance of ASMGMO Force Estimation

The ASMGMO was tested with a step change in interaction force. The results were compared against a standard Generalized Momentum Observer (GMO) and a fixed-gain Sliding Mode Observer (SMO). Key performance metrics are summarized below.

| Observer Type | Settling Time $T_s$ (ms) | Steady-State Error $E_{ss}$ (N) | Overshoot $M_p$ (%) | ITAE Performance Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Momentum Observer (GMO) | 1950 | 4.47 | 0.0 | 45.27 |

| Fixed-Gain Sliding Mode Observer (SMO) | 450 – 1400 | 0.08 – 2.84 | 2.8 – 7.7 | 3.27 – 10.83 |

| Proposed ASMGMO | 280 – 320 | 0.02 – 1.46 | 1.4 – 3.7 | 3.21 – 6.03 |

The ASMGMO demonstrated superior performance, reducing the settling time by over 80% compared to the GMO and by 30-70% compared to the fixed-gain SMO. Its steady-state error was also minimized, and the adaptive gains effectively managed the trade-off between convergence speed and chattering, resulting in a lower ITAE (Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error) score, which comprehensively evaluates tracking speed and accuracy.

Performance of SAPSO-RLS Stiffness Identification

The SAPSO-RLS algorithm was tested with a time-varying environment stiffness profile, including step changes. The following table compares its identification accuracy and speed against standard PSO-RLS and basic RLS.

| Algorithm | Convergence Time after Step (ms) | RMSE of $K_e$ Estimate (N/m) | ITAE for Identification Error | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Recursive Least Squares (RLS) | 300 – 400 | ~120 | 15.0 – 24.0 | Slow convergence, lags behind steps. |

| PSO-initialized RLS (PSO-RLS) | 130 – 170 | ~45 | 1.8 – 3.0 | Faster than RLS, but can get trapped. |

| Proposed SAPSO-RLS | 20 – 40 | ~15 | 0.8 – 0.9 | Fastest convergence, most accurate, robust to large changes. |

The SAPSO-RLS method showed a clear advantage, particularly in handling the large stiffness variations expected when clamping different roots. The SA phase enabled a better global initial guess, allowing the RLS to lock onto the true parameter value rapidly after a change. This rapid and accurate identification is crucial for the subsequent adaptive control laws in the end effector.

Overall Clamping Force Control Performance

The complete adaptive admittance control (AAC) system was simulated for a clamping scenario with a desired force $F_d = 200\text{N}$ and an environment stiffness $K_e = 1000 \text{N/m}$. The results were compared against the benchmark controllers (FAC and VAC). The key transient and steady-state metrics are quantified below.

| Performance Metric | Fixed Admittance Control (FAC) | Variable-Stiffness Adaptive Control (VAC) | Proposed Adaptive Admittance Control (AAC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Settling Time ($T_{s,5\%}$) | 1600 ms | 3060 ms | 520 ms |

| Maximum Force Overshoot | 0 N (30.96%) | 61.9 N (30.96%) | 5.3 N (2.64%) |

| Steady-State Force Error | 0 N | 3.05 N | 0 N |

| ITAE of Force Tracking | 39.17 | 66.88 | 2.28 |

| Root Damage Risk | High (Overshoot) | High (Overshoot & Error) | Very Low |

The proposed AAC method outperforms the others comprehensively. It achieves the fastest settling time (over 3x faster than VAC and 67% faster than FAC) by adaptively tuning both stiffness and damping. Critically, it maintains a very low overshoot (under 3%) compared to VAC’s significant 31% overshoot, which could damage a fragile root. It also drives the steady-state error to zero, unlike the VAC. The exceptionally low ITAE value for AAC confirms its overall superior tracking performance—balancing speed and accuracy—for the end effector.

Furthermore, robustness tests were conducted by introducing measurement noise, sudden changes in $K_e$, and external disturbances. The AAC system consistently maintained stable force regulation with minimal performance degradation, whereas the FAC and VAC systems exhibited larger errors, longer recovery times, or sustained oscillations.

Conclusion and Discussion

This paper has presented a holistic solution for achieving precise and gentle clamping force control in a robotic end effector designed for plant root tensile testing. The core challenge of operating without direct force sensing and in the face of unknown, variable root stiffness has been addressed through an integrated adaptive control framework.

The primary contributions are threefold. First, the Adaptive Sliding Mode Generalized Momentum Observer (ASMGMO) provides accurate, real-time estimation of the root-end effector interaction force. Its adaptive gains ensure robust performance and fast convergence, outperforming traditional observers. Second, the hybrid SAPSO-RLS algorithm enables rapid online identification of the environmental stiffness parameter. By combining the global search capability of Simulated Annealing with the local efficiency of Particle Swarm Optimization and the tracking ability of Recursive Least Squares, this method quickly converges to an accurate stiffness estimate, even after abrupt changes. Third, these estimates feed into an adaptive admittance control law. This law intelligently updates the target position and dynamically adjusts the virtual stiffness and damping parameters of the admittance model. This dual adaptation ensures that the end effector exhibits an optimal dynamic response—fast engagement with minimal overshoot and zero steady-state error—tailored to the specific root being clamped.

Simulation results demonstrate the clear superiority of the proposed method over conventional fixed-parameter or partially adaptive schemes. The system exhibits significantly faster force regulation, effectively eliminates damaging force overshoot, and maintains excellent tracking stability. This translates directly to a higher success rate in tensile tests by preventing root damage at the clamp points, thereby yielding more reliable biomechanical data.

Future work will focus on the physical implementation of the end effector and the control algorithms on embedded hardware, conducting extensive experimental trials with real plant roots. Investigating more complex, nonlinear contact models for the identification phase and extending the framework to manage anisotropic root properties could further enhance the system’s capability and applicability in ecological and geotechnical research.