In the evolving landscape of robotics, autonomous navigation stands as a cornerstone for intelligent robots, enabling them to operate independently in complex and dynamic environments. Traditional navigation systems relying on single sensors, such as LiDAR or cameras, often face limitations: LiDAR lacks texture perception, cameras are sensitive to lighting variations, and inertial measurement units (IMUs) suffer from cumulative errors. To overcome these challenges, multi-sensor fusion has emerged as a pivotal approach, integrating complementary data from various sensors to enhance robustness, accuracy, and adaptability. This article presents a comprehensive framework for autonomous navigation in intelligent robots, leveraging the synergy of LiDAR, visual cameras, and IMUs. Through a detailed exploration of data fusion, environmental perception, path planning, and motion control, I demonstrate how this framework achieves superior performance in diverse scenarios, supported by experimental validation. The goal is to advance the capabilities of intelligent robots, ensuring reliable navigation in real-world applications such as indoor logistics, service robotics, and autonomous exploration.

The foundation of autonomous navigation in intelligent robots lies in the cooperative perception of multiple sensors. Each sensor type offers unique advantages and drawbacks, and their integration forms a robust sensing suite. LiDAR provides precise geometric data through time-of-flight measurements, typically with a range of up to 100 meters and a scanning frequency of 10 Hz. It excels in capturing spatial structures but may fail in featureless areas. Visual cameras, especially stereo setups, deliver rich texture and color information at high frame rates (e.g., 30 fps), enabling feature-based localization and scene recognition. However, cameras are prone to illumination changes and motion blur. IMUs, with high-frequency outputs (e.g., 200 Hz), measure acceleration and angular velocity, offering real-time motion estimation but accumulating drift over time. By fusing these modalities, intelligent robots can achieve a more complete and accurate perception of their surroundings. The technical basis for this synergy involves understanding sensor characteristics, calibration, and synchronization. For instance, data from LiDAR and cameras must be temporally and spatially aligned, often achieved through hardware triggers or software timestamp matching. This cooperative perception enables intelligent robots to maintain situational awareness even in challenging conditions, such as low-light environments or dynamic obstacles.

To implement autonomous navigation in intelligent robots, I propose a multi-sensor fusion framework that encompasses data acquisition, processing, fusion, and control. The framework is designed to be modular and scalable, allowing for integration with various robotic platforms. The key components include multi-sensor data fusion, environment perception and simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), path planning and decision-making, and motion control and execution. Each component is elaborated below with formulas and tables to summarize critical aspects.

Multi-Sensor Data Fusion

Data fusion is the core of enhancing perception in intelligent robots. It involves acquiring raw data from sensors, preprocessing to remove noise, extracting features, and fusing information using advanced algorithms. For LiDAR, point clouds are generated with thousands of points per scan, which are filtered using statistical methods. A common approach is statistical outlier removal, where points beyond a threshold based on mean and standard deviation of neighbor distances are discarded. For a point cloud, the distance to neighbors is computed, and if the distance exceeds $\mu + 2\sigma$, where $\mu$ is the mean and $\sigma$ is the standard deviation, the point is considered noise. This threshold retains approximately 95.4% of data in a normal distribution, balancing noise removal and data preservation. After filtering, voxel grid downsampling reduces data volume by 40% using a grid size of 0.05 m. For visual data, images from stereo cameras are undistorted using pinhole camera models and enhanced via histogram equalization in YUV space to mitigate lighting effects. IMU data is calibrated by removing bias computed from static measurements and applying temperature compensation. Feature extraction follows: LiDAR features include edges and planes based on eigenvalue analysis of local point covariances. For a point $p_i$ with neighbors, the covariance matrix $C$ is computed:

$$C = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} (p_j – \bar{p})(p_j – \bar{p})^T$$

where $\bar{p}$ is the centroid of neighbors. Eigenvalues $\lambda_1, \lambda_2, \lambda_3$ (sorted descending) define linearity $L$ and planarity $P$:

$$L = \frac{\lambda_1 – \lambda_2}{\lambda_1}, \quad P = \frac{\lambda_2 – \lambda_3}{\lambda_1}$$

Points with $L > 0.7$ are edge features, and those with $P > 0.6$ and $L < 0.3$ are plane features. Visual features use ORB (Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF) descriptors, providing scale and rotation invariance through a pyramid of images with a scale factor of 1.2.

Fusion is performed using an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) framework to handle asynchronous measurements. The state vector $x$ includes 15 dimensions: position $p \in \mathbb{R}^3$, orientation as a quaternion $q \in \mathbb{R}^4$, velocity $v \in \mathbb{R}^3$, and sensor biases $b_a, b_g \in \mathbb{R}^3$ for accelerometer and gyroscope. The prediction step uses IMU data to propagate state via kinematic equations:

$$p_k = p_{k-1} + v_{k-1} \Delta t + \frac{1}{2} R_{k-1} a_k \Delta t^2$$

$$v_k = v_{k-1} + R_{k-1} a_k \Delta t$$

where $R_{k-1}$ is the rotation matrix from orientation $q_{k-1}$, $a_k$ is the measured acceleration, and $\Delta t$ is the time interval. The covariance matrix $P$ is updated using the Jacobian of the motion model. In the update step, when LiDAR or visual observations arrive, residuals are computed—e.g., point-to-plane distances for LiDAR or re-projection errors for visual features. The Kalman gain $K$ adjusts the state estimate:

$$K_k = P_{k|k-1} H_k^T (H_k P_{k|k-1} H_k^T + M)^{-1}$$

where $H_k$ is the observation Jacobian and $M$ is the observation noise covariance. This fusion allows intelligent robots to maintain accurate localization by weighting sensor contributions based on uncertainty.

| Sensor Type | Data Rate | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiDAR | 10 Hz | Precise geometry, range up to 100 m | No texture, sensitive to specular surfaces |

| Visual Camera | 30 fps | Rich texture, color information | Lighting-dependent, motion blur |

| IMU | 200 Hz | High-frequency motion data | Drift accumulation, noise |

Environmental Perception and SLAM Modeling

Environmental perception in intelligent robots integrates geometric and texture data to build a consistent map while localizing within it. The SLAM process uses a feature-based sparse representation, combining LiDAR features and visual landmarks. Keyframes are created when motion exceeds 0.5 m or rotation exceeds 15°, each storing pose estimates, sensor data, and features. New features are added to the map after quality checks, and their 3D coordinates are optimized through multi-view observations. To maintain global consistency, a pose graph optimization is employed, where nodes represent robot poses and edges represent constraints from sensor observations. The optimization minimizes the sum of weighted squared errors:

$$\min_x \sum_{i,j} e_{ij}^T \Omega_{ij} e_{ij}$$

where $e_{ij}$ is the error between poses $i$ and $j$, and $\Omega_{ij}$ is the information matrix. This is solved iteratively using Gauss-Newton methods. Loop closure detection utilizes a visual bag-of-words model, clustering ORB descriptors into a 10,000-word vocabulary. When a keyframe’s visual histogram similarity exceeds 0.8, a loop candidate is triggered and verified via RANSAC, adding a loop edge to the graph for global optimization to reduce drift. This approach enables intelligent robots to operate in environments with varying textures and dynamics, adapting to changes such as moving obstacles or lighting shifts. For instance, in low-texture corridors, LiDAR features dominate, while in rich-texture areas, visual features enhance accuracy. The system dynamically adjusts sensor weights based on confidence metrics, ensuring robustness.

| Perception Factor | Sensor Contribution | Adaptation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric Structure | LiDAR edge/plane features | Weighted fusion based on feature density |

| Texture Information | Visual ORB features | Histogram equalization for lighting |

| Dynamic Obstacles | Multi-frame consistency checks | Temporal filtering and motion detection |

Path Planning and Decision Making

Path planning for intelligent robots involves both global and local strategies to navigate efficiently and safely. Global planning uses the A* algorithm on a grid map with 0.1 m resolution. The algorithm evaluates nodes based on a cost function $f(n) = g(n) + h(n)$, where $g(n)$ is the actual cost from the start node and $h(n)$ is the heuristic cost to the goal, typically Euclidean distance. This guarantees optimal path finding in static environments. For local planning, the Dynamic Window Approach (DWA) searches in velocity space $(v, \omega)$ to generate safe trajectories. Feasible velocities are constrained by kinematics and dynamics, and for each candidate, a trajectory is simulated over 1 second. The trajectory is evaluated using a scoring function $G(v, \omega)$:

$$G(v, \omega) = \alpha \cdot d(v, \omega) + \beta \cdot h(v, \omega) + \gamma \cdot s(v, \omega)$$

where $d(v, \omega)$ is the minimum distance to obstacles, $h(v, \omega)$ is the alignment with the global path, and $s(v, \omega)$ is the speed profile favoring higher velocities. The weights $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ are adjusted based on environmental complexity—e.g., higher $\alpha$ in cluttered spaces. This allows intelligent robots to react in real-time to dynamic obstacles while progressing toward goals. Decision-making incorporates risk assessment; for example, if sensor confidence drops, the robot may slow down or replan. The integration of multi-sensor data ensures that path planning accounts for both geometric obstacles (from LiDAR) and semantic information (from cameras), enabling intelligent robots to navigate through diverse scenarios such as crowded halls or uneven terrain.

Motion Control and Execution

Motion control in intelligent robots translates planned paths into precise wheel commands. A cascaded PID control architecture is used, with an outer loop for velocity control and an inner loop for current control. The outer loop computes acceleration commands based on velocity error $e_v = v_{desired} – v_{actual}$:

$$a_{cmd} = K_p e_v + K_i \int e_v dt + K_d \frac{de_v}{dt}$$

where $K_p, K_i, K_d$ are tuned gains for responsive and stable control. The inner loop converts acceleration to motor torque, considering motor dynamics and inertia. For differential-drive robots, wheel velocities $v_L$ and $v_R$ are derived from linear velocity $v$ and angular velocity $\omega$:

$$v_L = v – \frac{b \omega}{2}, \quad v_R = v + \frac{b \omega}{2}$$

where $b$ is the wheelbase (0.45 m in our setup). Commands are smoothed with a first-order low-pass filter (cut-off 5 Hz) and executed at 100 Hz. Feedback from encoders and IMU monitors consistency, triggering safety mechanisms if anomalies are detected. This control scheme ensures that intelligent robots accurately follow trajectories while compensating for slippage or disturbances, crucial for navigation in unpredictable environments.

Experiments and Performance Testing

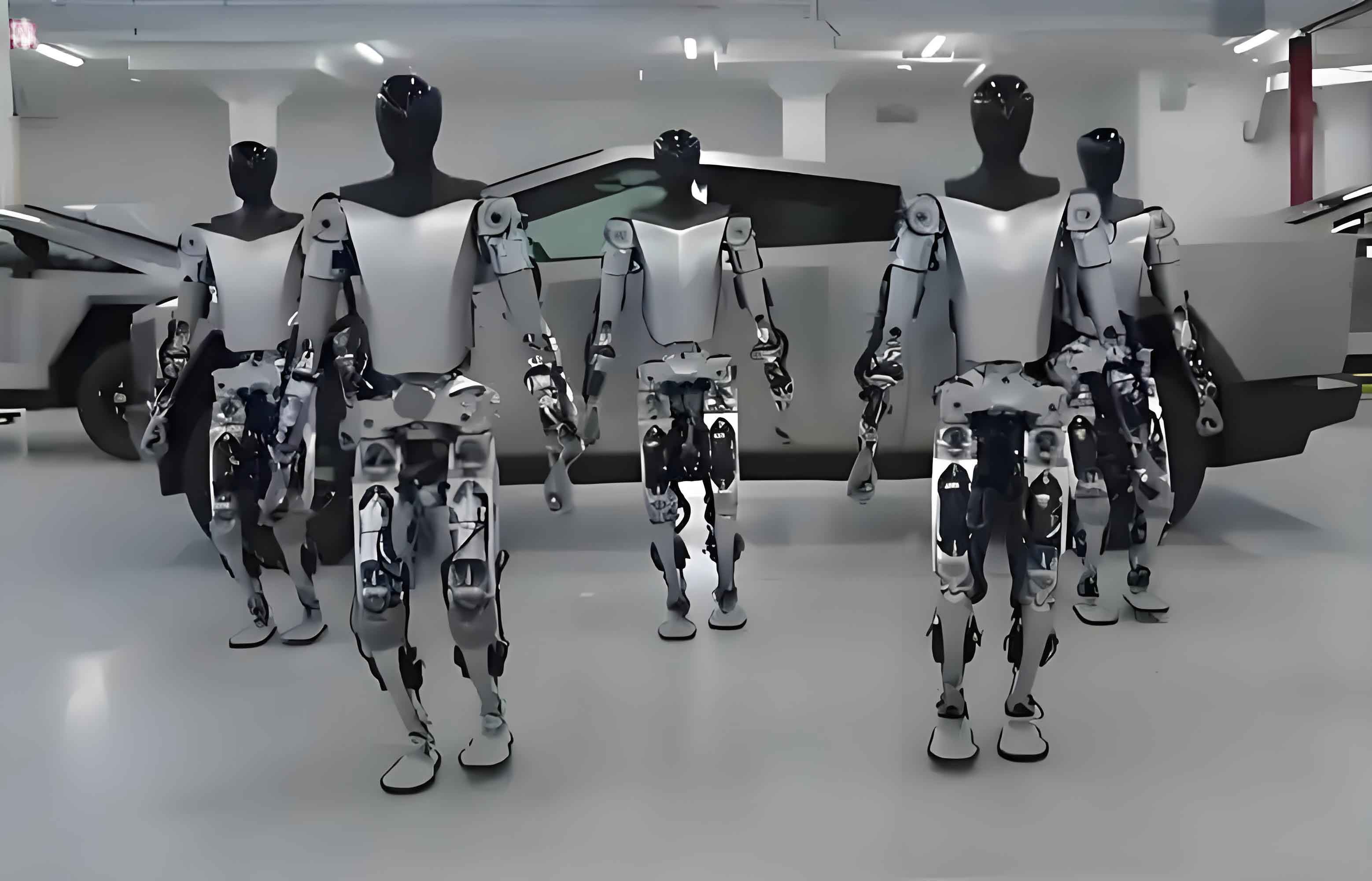

To validate the proposed framework, experiments were conducted in a 200 m² indoor environment with corridors, rooms, static obstacles, and 3-5 moving pedestrians. The intelligent robot platform featured differential drive, a 16-line LiDAR, stereo camera, and 6-axis IMU, powered by an Intel i7 processor and NVIDIA GPU. Three navigation schemes were compared: LiDAR-only, LiDAR-IMU fusion, and multi-sensor fusion (LiDAR-camera-IMU). Each performed 10 navigation tasks over 150 m, with metrics including positioning error, mapping completeness, path planning success rate, and computational time. Positioning error was measured using an OptiTrack motion capture system as ground truth.

The results demonstrate the superiority of multi-sensor fusion for intelligent robots. In normal conditions, the average positioning error was 0.08 m, compared to 0.23 m for LiDAR-only and 0.15 m for LiDAR-IMU fusion. This represents a 65.2% reduction from LiDAR-only, attributed to visual constraints and IMU motion tracking. Mapping completeness reached 94.7%, indicating detailed environment reconstruction. Path planning success rate was 96.3%, outperforming other schemes. In challenging scenarios like sudden illumination changes, the adaptive weight adjustment in fusion maintained error within 0.12 m and success rate at 91.3%, while LiDAR-only degraded to 0.31 m error and 65.2% success. Computational time averaged 68 ms per cycle, meeting real-time requirements. These findings highlight how multi-sensor fusion enhances the adaptability and reliability of intelligent robots in complex settings.

| Navigation Scheme | Avg. Positioning Error (m) | Max Positioning Error (m) | Mapping Completeness (%) | Path Planning Success Rate (%) | Avg. Computation Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiDAR-only | 0.23 | 1.47 | 82.5 | 78.0 | 45 |

| LiDAR-IMU Fusion | 0.15 | 0.89 | 88.3 | 87.0 | 52 |

| Multi-Sensor Fusion | 0.08 | 0.31 | 94.7 | 96.3 | 68 |

Further analysis examined performance under varying lighting conditions. The positioning error over time showed that multi-sensor fusion remained stable within 0.1 m in normal light, while LiDAR-only fluctuated up to 0.4 m in dim light. Trajectory comparisons revealed that in illumination突变 regions, multi-sensor fusion deviated only 0.3 m from the ideal path, versus 2.2 m for LiDAR-only. This robustness stems from the synergy of sensors: when visual data degrades, LiDAR and IMU compensate, and vice versa. Such capabilities are essential for intelligent robots operating in real-world applications where environmental conditions are unpredictable.

Conclusion

This article has presented a comprehensive framework for autonomous navigation in intelligent robots through multi-sensor fusion. By integrating LiDAR, visual cameras, and IMUs, the framework addresses limitations of single-sensor systems, offering enhanced accuracy, robustness, and adaptability. Key contributions include a detailed data fusion pipeline using Extended Kalman Filtering, feature-based SLAM with graph optimization, dynamic path planning with A* and DWA, and precise motion control via cascaded PID. Experimental results confirm significant improvements in positioning error, mapping quality, and path planning success across normal and challenging scenarios. The adaptive weight adjustment mechanism ensures that intelligent robots maintain performance even under光照突变 or dynamic obstacles. Future work may explore deep learning integration for semantic perception or swarm coordination. Overall, multi-sensor fusion is a transformative approach for advancing autonomous navigation, enabling intelligent robots to operate reliably in complex environments and paving the way for broader adoption in industries like logistics, healthcare, and exploration.