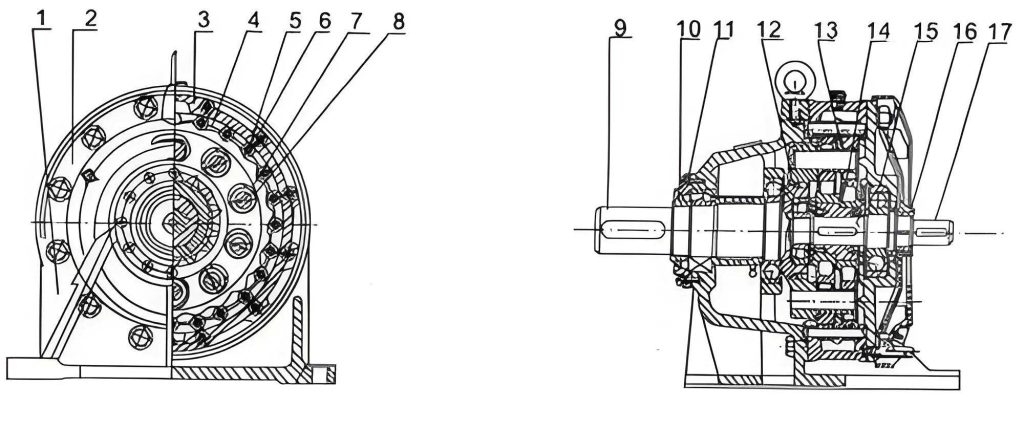

In my extensive experience with industrial power transmission, the cycloidal drive stands out as a remarkably efficient and robust speed reduction mechanism. Its unique principle of operation, based on cycloidal motion, offers high torque density, compact design, and excellent overload capacity. These attributes make the cycloidal drive a preferred choice in numerous sectors, including chemical processing, pharmaceuticals, food production, and petrochemicals. Specifically, in applications like vertical reactor stirrers, the cycloidal drive is often tasked with transmitting torque to agitator shafts. However, a critical challenge arises here: the standard cycloidal drive is engineered primarily to handle torsional loads, not substantial axial forces. When deployed in a vertical stirrer, the agitator shaft and impeller can generate significant axial thrust, especially during process phases such as liquid crystallization, viscosity changes, or start-up under high-density media. This unaccounted axial load imposes severe stress on the internal bearings of the cycloidal drive, leading to premature fatigue, increased friction, reduced transmission efficiency, and ultimately, catastrophic failure. The core objective of this discussion is to explore and detail effective strategies for axial load management, ensuring that the inherent advantages of the cycloidal drive are fully realized in demanding vertical stirring applications.

The fundamental issue stems from the design philosophy of most standard cycloidal speed reducers. They incorporate bearings—typically a combination of needle roller bearings and deep groove ball bearings—that are sized for radial loads and moderate axial loads incidental to operation. The axial force \( F_a \) from a vertical stirrer, however, can be modeled as a combination of hydrodynamic drag and static pressure differential. For a simple impeller, the axial thrust can be approximated by:

$$ F_a = K_T \cdot \rho \cdot N^2 \cdot D^4 $$

where \( K_T \) is the thrust coefficient (dependent on impeller geometry), \( \rho \) is the fluid density, \( N \) is the rotational speed, and \( D \) is the impeller diameter. During crystallization, \( \rho \) can increase dramatically, and the fluid may exhibit non-Newtonian behavior, causing \( F_a \) to spike unpredictably. When this force is directly transmitted to the cycloidal drive’s output bearing, the equivalent dynamic load \( P \) on the bearing increases, drastically reducing its calculated L10 life according to the standard bearing life equation:

$$ L_{10} = \left( \frac{C}{P} \right)^p $$

For ball bearings, \( p = 3 \), and \( C \) is the basic dynamic load rating. The equivalent load \( P \) for combined radial and axial loads is given by:

$$ P = X \cdot F_r + Y \cdot F_a $$

where \( F_r \) is the radial load, and \( X \) and \( Y \) are factors determined by bearing type and the ratio \( F_a / F_r \). For the cycloidal drive’s bearings, a large \( F_a \) can make \( Y \cdot F_a \) the dominant term, leading to a high \( P \) and a precipitous drop in \( L_{10} \). This is why an external axial load relief or “unloading” device is not merely an accessory but a necessity for reliable long-term operation. Over the years, we have developed and refined several practical schemes to address this. The following sections delineate three primary design philosophies for axial load management in systems employing a cycloidal drive.

The first scheme involves integrating a dual-support-point structure directly into the agitator shaft assembly. This design physically decouples the majority of the axial load from the cycloidal drive output shaft. In this configuration, the cycloidal drive is mounted atop the reactor, and its output shaft is connected to the agitator shaft via a flexible coupling designed to transmit torque while accommodating minor misalignments. The key feature is the introduction of two independent radial bearings (e.g., deep groove ball bearings or angular contact bearings arranged back-to-back) housed in a separate bearing pedestal or a modified reactor head. This pedestal is mounted between the cycloidal drive and the reactor vessel. The agitator shaft passes through this pedestal, and the dual bearings take up the entire axial load as well as radial loads, leaving the cycloidal drive to experience only pure torque. The mechanics can be summarized by ensuring that the sum of forces on the agitator shaft satisfies:

$$ \sum F_y = F_a – R_{A} – R_{B} = 0 $$

where \( R_{A} \) and \( R_{B} \) are the reaction forces at the dual support bearings. The cycloidal drive output shaft connection point then has a theoretical axial force of zero. This scheme’s advantage is profound stability; it eliminates shaft whip and lateral vibration, which are common in long vertical shafts. Reduced vibration directly translates to lower wear on the cycloidal drive’s internal components, especially the cycloidal discs and pin teeth. A simplified comparison of load paths is shown below:

| Component | Without Unloading Device | With Dual-Support Scheme |

|---|---|---|

| Cycloidal Drive Output Bearing | Carries full \( F_a \) and \( F_r \) | Carries minimal \( F_r \) only |

| Separate Thrust Bearing Assembly | Not present | Carries full \( F_a \) and radial loads |

| Shaft Stability | Lower, prone to deflection | High, rigidly supported |

| Maintenance Focus | Cycloidal drive internals | External bearing cartridge |

While this scheme is highly effective, it does add mechanical complexity, requires precise alignment during installation, and increases the overall height of the drive train. However, for large reactors with high-power cycloidal drives, this is often the most reliable choice.

The second scheme, which we have deployed in environments demanding exceptional corrosion resistance and sealing, incorporates a specialized mechanical seal arrangement that also functions as an axial thrust buffer. In this design, the agitator shaft is supported by a single bearing near the impeller, but a custom-designed seal housing at the reactor penetration point is engineered with integral thrust washers or a hydrodynamic face seal. The seal not only prevents process fluid leakage but is also designed with a large surface area to distribute axial loads. The principle here leverages the seal’s construction to create a hydrostatic or hydrodynamic pressure film that partially supports the axial load. The axial force is partially balanced by the pressure \( p \) developed in the sealing gap:

$$ F_{a, balanced} = \int_A p \, dA $$

where \( A \) is the effective area of the seal face. The remaining axial load is then transmitted to a rugged thrust collar seated in the seal housing, not to the cycloidal drive. This design is particularly advantageous when handling aggressive chemicals or high-purity products, as it combines leak containment with load management. The cycloidal drive is again connected via a torque-only coupling. The table below contrasts key parameters:

| Design Aspect | Standard Seal | Seal-Based Unloading Scheme |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Leak Prevention | Leak Prevention + Axial Load Support |

| Axial Load Path | Through shaft to drive | Diverted to seal housing/structure |

| Material Requirements | Corrosion-resistant face | Corrosion-resistant, high-strength face & thrust components |

| Impact on Cycloidal Drive | High axial stress | Negligible axial stress |

This approach requires careful selection of seal materials (like silicon carbide, tungsten carbide, or PTFE composites) and precise control of the fluid film dynamics. It is a sophisticated solution that merges two critical functions, simplifying the overall mechanical layout while providing excellent protection for the cycloidal drive.

The third scheme embodies simplicity and elegance, especially suitable for medium-duty applications or where frequent maintenance access is required. This design completely removes the lower bearing support for the agitator shaft. Instead, a sacrificial sleeve or bushing—made from a corrosion-resistant material like stainless steel, Hastelloy, or even ceramic—is installed at the bottom of the reactor vessel. This sleeve acts as a centering guide during start-up and shutdown. During operation, the hydrodynamic forces generated by the rotating impeller create a self-centering, fluid-borne effect. The agitator shaft achieves a state of hydrodynamic equilibrium, where the radial and axial forces are balanced by the fluid motion, effectively “floating” the shaft. The axial thrust is balanced by the pressure distribution on the impeller itself, a concept derived from pump theory. The balance can be expressed as:

$$ F_a = \Delta p \cdot A_{impeller} + \rho \cdot Q \cdot (v_{2} – v_{1}) $$

where \( \Delta p \) is the pressure difference across the impeller, \( A_{impeller} \) is the effective area, \( Q \) is the flow rate, and \( v \) are fluid velocities. In a well-designed system, this balance minimizes the net axial force transmitted upward to the drive train. The cycloidal drive is connected, often with a rigid coupling since misalignment is minimized by the self-centering action, and experiences only a fraction of the theoretical axial load. The primary advantage is mechanical simplicity: fewer parts, no external bearing housing, and easier installation. The trade-off is a reliance on steady-state fluid dynamics; during start-up, before full fluid motion is established, the sleeve provides initial alignment and wears minimally. This scheme is highly effective for processes with consistent fluid properties and where the cycloidal drive is not oversized. The following formula helps in sizing the sleeve for wear resistance based on the PV (Pressure-Velocity) limit:

$$ PV = p \cdot v \leq (PV)_{max} $$

where \( p \) is the contact pressure and \( v \) is the sliding velocity at the sleeve interface. Choosing a material with a high \( (PV)_{max} \) rating ensures longevity.

To synthesize these concepts and aid in selection, a comprehensive comparative analysis is essential. The table below evaluates the three schemes across multiple operational and economic criteria, emphasizing their interaction with the core cycloidal drive.

| Evaluation Criterion | Scheme 1: Dual-Support Structure | Scheme 2: Integrated Seal Thrust Device | Scheme 3: Hydrodynamic Self-Centering with Sleeve |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Complexity | High (additional bearing housing, alignment) | Moderate-High (specialized seal design) | Low (minimal added components) |

| Axial Load Capacity | Very High (designed for full load) | High (limited by seal face area & pressure) | Moderate (depends on fluid dynamics) |

| Protection for Cycloidal Drive | Excellent (complete isolation) | Very Good (significant diversion) | Good (reduction via fluid balance) |

| Corrosion Resistance | Depends on bearing/seal materials | Excellent (integral with process seal) | Excellent (sleeve material can be highly inert) |

| Maintenance Requirements | Moderate (lubrication of external bearings) | Moderate (seal face inspection/replacement) | Low (occasional sleeve inspection) |

| Ideal Application Context | Large, high-thrust reactors; critical processes | Chemical reactors with aggressive media; high containment needs | Medium-duty mixers; processes with stable fluid properties |

| Impact on Cycloidal Drive Life | Maximizes life by eliminating axial stress | Greatly extends life by reducing axial stress | Significantly improves life by mitigating axial stress |

Beyond the qualitative analysis, quantitative life extension for the cycloidal drive can be modeled. Let’s consider a typical scenario where a cycloidal drive without unloading experiences an axial force \( F_a = 5000 \, N \). Assume its output bearing has a dynamic load capacity \( C = 15000 \, N \) and sees a radial load \( F_r = 2000 \, N \). Using the equivalent load formula with typical factors \( X = 0.56 \) and \( Y = 1.5 \) (for a deep groove ball bearing with \( F_a/F_r > e \)), we get:

$$ P_{no-unload} = 0.56 \cdot 2000 + 1.5 \cdot 5000 = 1120 + 7500 = 8620 \, N $$

The L10 life is:

$$ L_{10, no-unload} = \left( \frac{15000}{8620} \right)^3 \approx \left( 1.74 \right)^3 \approx 5.27 \, \text{million revolutions} $$

Now, with an effective unloading scheme that reduces the axial force on the cycloidal drive bearing to, say, \( F_a’ = 500 \, N \), and assuming the radial load remains, the new equivalent load for the same bearing (now with \( F_a’/F_r = 0.25 \), potentially changing factors to \( X=1, Y=0 \)) would be:

$$ P_{unload} = 1 \cdot 2000 + 0 \cdot 500 = 2000 \, N $$

The new life becomes:

$$ L_{10, unload} = \left( \frac{15000}{2000} \right)^3 = 7.5^3 = 421.875 \, \text{million revolutions} $$

This represents an approximately 80-fold increase in calculated bearing life, vividly illustrating why protecting the cycloidal drive from axial loads is paramount. This calculation underscores the core message: integrating an axial load management system is an investment that pays dividends through dramatically reduced downtime and maintenance costs for the cycloidal drive unit.

In practical implementation, several additional engineering considerations come into play regardless of the chosen scheme. First, alignment between the cycloidal drive output and the agitator shaft is critical. Even with flexible couplings, gross misalignment can induce parasitic radial loads that defeat the purpose of the unloading device. Laser alignment tools are recommended during installation. Second, material selection for all components in contact with the process fluid must account for corrosion, erosion, and temperature. For instance, in a pharmaceutical reactor, a polished 316L stainless steel sleeve (Scheme 3) or ceramic-coated bearings (Scheme 1) might be specified. Third, lubrication of any external bearings in Schemes 1 and 2 must be compatible with the process environment; double-sealed or greased-for-life bearings are common choices. Fourth, monitoring and diagnostics can be enhanced by installing vibration sensors or load cells on the bearing housings to track the actual axial load being diverted, providing early warning of process changes or mechanical wear.

The versatility of the cycloidal drive makes it suitable for a vast range of stirring duties, from gentle blending to high-shear mixing. However, its longevity is inextricably linked to proper load management. The schemes described—the robust dual-support structure, the multifunctional integrated seal, and the elegantly simple hydrodynamic sleeve—each offer a pathway to achieve this. They transform the cycloidal drive from a component potentially vulnerable to axial overload into a durable, reliable heart of the mixing system. In many retrofit projects, we have observed that adding one of these unloading devices to an existing installation suffering from frequent cycloidal drive failures can eliminate those failures entirely, validating the design principles. The choice among them depends on a thorough analysis of the specific application: the magnitude and variability of axial thrust, chemical environment, space constraints, maintenance philosophy, and total cost of ownership.

To further generalize, the principles discussed are not limited to vertical reactor stirrers. Any application where a cycloidal drive might be subjected to unintended axial loads—such as in certain conveyor drives, winches, or vertical pump drives—can benefit from similar engineering interventions. The core idea is to always respect the fundamental design intent of the cycloidal drive: optimal performance under torsional load. By conscientiously managing auxiliary loads through dedicated mechanical systems, we unlock the full potential of this ingenious speed reduction technology. The cycloidal drive, when properly protected, consistently delivers the high torque, compact footprint, and reliable service that modern industry demands. Through continuous refinement of these unloading schemes, we contribute to more efficient, safer, and more productive operations across the chemical, pharmaceutical, food, and biotechnology sectors, ensuring that the cycloidal drive remains a cornerstone of industrial motion control.