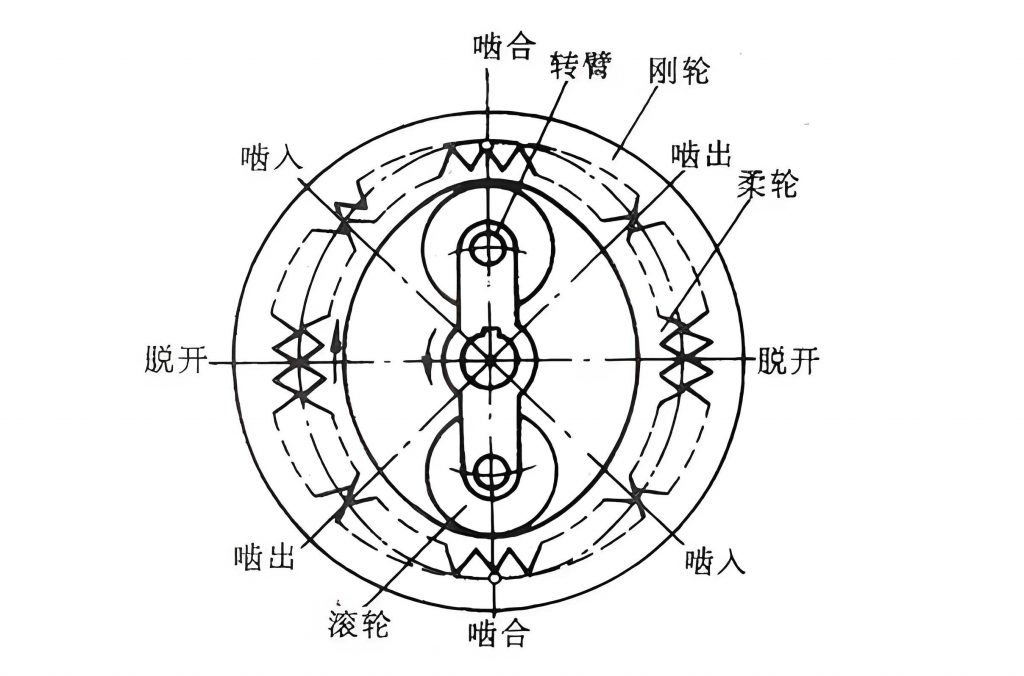

This article presents my in-depth analysis and findings on the precision hobbing of large modified flexsplines, a critical component in harmonic drive gear systems. As a researcher focused on advanced gear manufacturing, I aim to elucidate the unique formation mechanism during hobbing, quantify the inherent theoretical machining errors, and establish clear guidelines for optimizing process parameters to achieve superior gear accuracy. The harmonic drive gear, renowned for its compact size, high reduction ratio, and exceptional positional accuracy, relies heavily on the precision of its thin-walled, large-modification flexspline. The standard hobbing process, when applied to such gears with significant profile shift, can introduce substantial errors if not properly controlled. My work here is based on a rigorous simulation methodology validated by physical experiments, providing a reliable framework for analysis.

The core of my methodology involves establishing a precise mathematical model for the hobbing process. I begin by parameterizing the cutting edges of the hob. For an Archimedean hob, the axial tooth profile in its coordinate system \( O_1-X_1Y_1 \) is defined. Let \( s \) be the parameter along the hob axis \( X_1 \). The profile coordinates \( P_1(s) \) and the corresponding \( Y_1(s) \) value are given by:

$$ P_1(s) = [s, Y_1(s), 0, 1]^T $$

$$ Y_1(s) = \begin{cases}

r_h – h_{f1} & (x_2 < s \leq P_a / 2) \\

r_h + (P_a / 4 – s)\cot\alpha_x & (x_3 < s \leq x_2) \\

D_h / 2 – r_c + \sqrt{r_c^2 – (s – x_4)^2} & (x_4 < s \leq x_3) \\

D_h / 2 & (-x_4 < s \leq x_4)

\end{cases} $$

where \( r_h \) is the hob pitch radius, \( P_a \) is the axial pitch, \( \alpha_x \) is the axial pressure angle, \( D_h \) is the hob outside diameter, and \( r_c \) is the tip fillet radius. The transition points \( x_2, x_3, x_4 \) are calculated from hob geometry. This profile is then replicated around the hob axis to form the series of cutting edges. The \( k\)-th cutting edge, accounting for the helical lead, is expressed as:

$$ L_1^k(s) = M_1^k P_1(s) $$

$$ M_1^k = \begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & k P_a \gamma_s / (Z_L \gamma_s) \\

0 & \cos(2\pi k / Z_L) & -\sin(2\pi k / Z_L) & 0 \\

0 & \sin(2\pi k / Z_L) & \cos(2\pi k / Z_L) & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix} $$

Here, \( Z_L \) is the number of gashes, and \( \gamma_s \) is the helix lead angle (positive for right-hand hob).

The kinematic relationship between the hob and the workpiece is fundamental. The coordinate transformation chain from the hob edge \( L_1^k(s) \) to the workpiece coordinate system \( O_5-X_5Y_5Z_5 \) involves rotations and translations representing the hobbing motion: hob rotation \( \phi \), hob installation with axis crossing angle \( \gamma_i \), radial center distance \( a \), axial feed \( \mu(\phi) \), and workpiece rotation \( \psi(\phi) \). The resulting family of surfaces generated by the cutting edges in the workpiece space is:

$$ G_g^k(s, \phi) = M_5^4 M_4^2 M_2^1 L_1^k(s) $$

The transformation matrices are:

$$ M_2^1 = \begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & \cos\phi & \sin\phi & 0 \\

0 & -\sin\phi & \cos\phi & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

M_4^2 = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos\gamma_i & 0 & -\sin\gamma_i & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & a \\

\sin\gamma_i & 0 & \cos\gamma_i & \mu(\phi) \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}, \quad

M_5^4 = \begin{bmatrix}

\cos\psi & -\sin\psi & 0 & 0 \\

\sin\psi & \cos\psi & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix} $$

The axial feed per revolution of the workpiece is \( f \), and the feed function is \( \mu(\phi) = \pm N f \phi / (2\pi z) \), where \( N \) is hob thread starts, and \( z \) is gear teeth. The workpiece rotation is synchronized as \( \psi(\phi) = \pm N \phi / z \). The theoretical tooth flank of a straight, large modified involute gear is modeled parametrically. For the \( i \)-th tooth space, the coordinates \( F_i(\theta, w) \) and its normal vector \( n_i(\theta, w) \) are:

$$ F_i(\theta, w) = \begin{bmatrix}

\pm [r_b \sin(\theta – \Omega – i\cdot\Delta) – r_b \theta \cos(\theta – \Omega – i\cdot\Delta)] \\

r_b \cos(\theta – \Omega – i\cdot\Delta) + r_b \theta \sin(\theta – \Omega – i\cdot\Delta) \\

w \\

1

\end{bmatrix} $$

$$ n_i(\theta, w) = \frac{\partial F_i(\theta, w)}{\partial \theta} \times \frac{\partial F_i(\theta, w)}{\partial w} $$

Here, \( r_b \) is base radius, \( \theta \) is involute roll angle, \( w \) is axial coordinate, \( \Delta = 2\pi/z \) is angular pitch, and \( \Omega \) is a constant phase angle incorporating the modification \( x \).

The theoretical machining error is evaluated by finding the minimal normal distance from a point on the theoretical flank \( F_i(\theta_m, w_n) \) to the envelope of all cutting edge trajectories \( G_g^k(s, \phi) \). The error \( \delta_i(\theta_m, w_n) \) is positive if the deviation aligns with the outward normal. By evaluating this over a grid of points, the complete topological error map \( \delta_i(\theta, w) \) is constructed. Profile and lead errors are derived from this map by fixing one parameter.

My simulation and experimental verification confirm the model’s accuracy. I compared standard and large-modified gears. The results showed excellent agreement between simulated and measured profile/lead errors for both gear types, validating the error prediction model.

| Parameter | Gear 1 (Standard) | Gear 2 (Large Modified Flexspline) |

|---|---|---|

| Module \( m_n \) (mm) | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Profile Shift Coefficient \( x \) | 0 | 3 |

| Pressure Angle \( \alpha_n \) (°) | 20 | 20 |

| Number of Teeth \( z \) | 90 | 90 |

| Tip Diameter (mm) | 230 | 245 |

| Root Diameter (mm) | 218.75 | 233.75 |

The central finding for the harmonic drive gear flexspline is the unique error mechanism. For a standard gear, the central hob tooth (index k=0) primarily forms the final flank. However, for a large modified gear, the central tooth becomes ineffective near the tip region. The final tooth form near the tip is generated by cutting edges far from the center (e.g., k = ±36 or beyond). If the hob is not long enough, these outer edges do not fully engage, leading to “uncut” or insufficiently cut material at the tooth tip, causing significant profile error. This is a critical failure mode specific to hobbing large modified gears like those in harmonic drive gear systems.

I quantified this requirement. To avoid tip under-cutting for a specific harmonic drive gear flexspline (module 0.5, x=3, 200 teeth), the minimum required active hob length corresponds to the indices shown below. For complete cutting at the tip diameter of 104 mm, cutting edges up to k=41 and k=-41 are required, meaning a minimum of 83 active teeth are needed.

| Diameter (mm) | 103.544 | 103.658 | 103.772 | 103.886 | 104.000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Flank (k) | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 |

| Right Flank (k) | -37 | -38 | -39 | -40 | -41 |

The relationship between the minimum number of required active hob teeth \( N_{min} \) and the profile shift coefficient \( x \) is approximately linear and increasing, as shown by the formula derived from simulation data for a given gear set:

$$ N_{min} \approx 17 + 22x $$

This underscores that manufacturing a high-precision harmonic drive gear flexspline with large modification demands a specially long hob, unlike standard gear hobbing.

The second major source of error in harmonic drive gear flexspline hobbing is the lead error, manifesting as a waviness along the tooth face. This is intrinsically linked to the intermittent axial feed of the hob. The peak-to-valley lead error \( \Delta L_{max} \) is highly sensitive to the axial feed per revolution \( f \). My simulations establish a clear quantitative relationship. Reducing \( f \) dramatically improves the harmonic drive gear’s lead accuracy.

| Axial Feed \( f \) (mm/rev) | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max. Lead Error \( \Delta L_{max} \) (µm) | ~5.4 | ~2.4 | ~0.6 | ~0.15 |

The data fits a power-law relationship, which can be expressed as:

$$ \Delta L_{max} \propto f^{\,n} $$

where \( n \) is approximately 2 for the simulated conditions. This means halving the feed reduces the lead error to about one-quarter. This trade-off between productivity (high feed) and accuracy (low feed) is crucial for process planning in harmonic drive gear manufacturing.

My comprehensive error analysis, combining the under-cutting and lead waviness effects, provides a clear roadmap for improving harmonic drive gear flexspline hobbing precision:

- Hob Length Specification: Use a hob with sufficient active length, calculated based on the profile shift coefficient and tip diameter, to eliminate tip under-cutting errors. For the example flexspline, a hob with at least 83 active teeth is mandatory.

- Axial Feed Optimization: Select the axial feed \( f \) based on the required lead accuracy. For ultra-precision harmonic drive gear applications, a very low feed (e.g., 0.5 mm/rev or less) is necessary to minimize lead waviness. The relationship \( \Delta L_{max} \propto f^{\,2} \) serves as a guide for this decision.

Implementing these measures based on the simulated models allows for the production of harmonic drive gear flexsplines with significantly enhanced geometric accuracy. For instance, by applying a sufficiently long hob and reducing the feed to 0.5 mm/rev, the dominant profile error at the tip is eliminated, and the maximum lead error is reduced from over 5 µm to below 0.6 µm. This level of improvement is critical for achieving the near-zero-backlash and high positioning repeatability that harmonic drive gear systems are known for.

In conclusion, my analysis demonstrates that the hobbing of large modified flexsplines for harmonic drive gears is subject to unique error formation mechanisms distinct from standard gear hobbing. The primary challenges are tip under-cutting due to insufficient hob length and lead waviness due to axial feed. Through precise mathematical modeling and simulation, I have quantified these errors and derived practical formulas and relationships to control them. The key to high-precision manufacturing of the harmonic drive gear flexspline lies in specifying a long-enough hob and employing a sufficiently low axial feed rate. These findings provide a solid theoretical and practical foundation for optimizing the hobbing process, ultimately contributing to the performance and reliability of advanced harmonic drive gear systems in robotics, aerospace, and other precision applications. Future work may explore the interaction of these geometric errors with the loaded tooth contact and transmission error of the assembled harmonic drive gear.