The pursuit of precision, compactness, and reliability in modern robotic systems, including those deployed in demanding sectors such as agriculture, has driven the adoption of advanced transmission technologies. Among these, strain wave gearing, also commonly known as harmonic drive gearing, stands out for its exceptional characteristics. This transmission system offers high reduction ratios within a single stage, exceptional positional accuracy and repeatability, near-zero backlash, high torque capacity relative to its size and weight, and the ability to operate in confined spaces. These attributes make it particularly suitable for robotic joints, manipulator wrists, and other precision motion control applications where performance and form factor are critical.

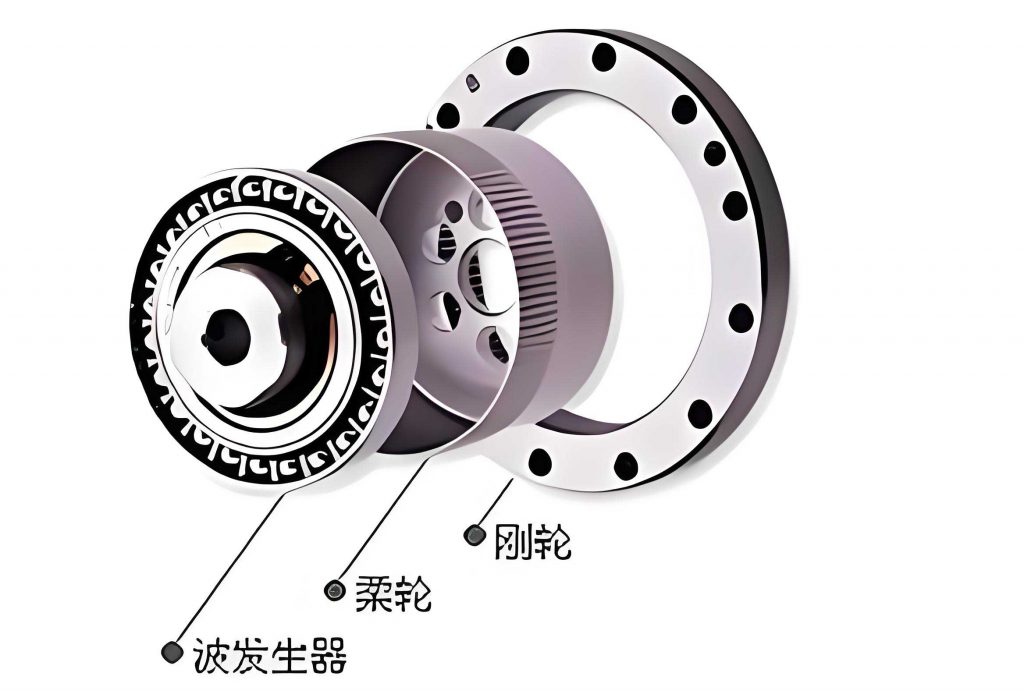

The fundamental operational principle of a strain wave gear relies on the controlled elastic deformation of a critical component: the flexspline. A typical strain wave gear assembly consists of three primary elements: a rigid Circular Spline, a flexible Flexspline, and a Wave Generator. The flexspline is a thin-walled, cup-shaped or hat-shaped component with external teeth. The wave generator, often an elliptical ball bearing or a multi-lobed cam, is inserted into the flexspline, forcing it into a controlled non-circular shape. This deformation causes the teeth of the flexspline to engage with the teeth of the stationary circular spline at two diametrically opposite regions (the major axis of the ellipse). Due to a slight difference in the number of teeth between the flexspline and the circular spline (usually by 2 or more teeth per wave generator lobe), a relative rotational motion is achieved between the wave generator input and the flexspline output (or vice-versa, depending on the design).

The very mechanism that gives the strain wave gear its advantages also subjects the flexspline to significant cyclical stress. During each revolution of the wave generator, the flexspline undergoes a complete elastic deformation cycle. This repeated loading in the plastic deformation range, although designed to be within the material’s endurance limit, makes fatigue failure the primary concern for the flexspline’s longevity. Therefore, a precise understanding of the stress distribution, deformation state, and identification of critical stress concentration zones within the flexspline is paramount for optimal design, material selection, and life prediction. This is where Finite Element Analysis (FEA) becomes an indispensable tool, allowing for a detailed virtual investigation that is often cost-prohibitive or extremely difficult to achieve through physical experimentation alone.

Analytical Foundation of Flexspline Mechanics

Before delving into the finite element methodology, it is instructive to review the classical analytical models that describe the deformation and stress state of a simplified flexspline. These models, often based on thin-shell theory, provide valuable closed-form solutions for initial sizing and understanding. For a cup-type flexspline, the radial deflection \( w(\phi) \) imposed by a two-lobe (elliptical) wave generator can be approximated as a function of the angular position \( \phi \) measured from the major axis:

$$ w(\phi) = w_0 \cos(2\phi) $$

where \( w_0 \) is the maximum radial deformation at the major axis (\( \phi = 0^\circ \)). The corresponding circumferential displacement \( v(\phi) \) is derived from the shell compatibility conditions:

$$ v(\phi) = -\frac{w_0}{2} \sin(2\phi) $$

Using these displacement fields, the membrane and bending stresses in the thin cylindrical body of the flexspline (ignoring the teeth initially) can be estimated. The bending stress along the axial direction \( \sigma_z \) and the circumferential direction \( \sigma_\phi \) are of primary interest. For a cylindrical shell of thickness \( s_1 \) and neutral radius \( r_m \), these stresses can be expressed as:

$$ \sigma_z = \frac{E s_1}{2 r_m^2} \left( \frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial \phi^2} + w \right) $$

$$ \sigma_\phi = \frac{E s_1}{2 r_m^2} \left( \frac{\partial^2 w}{\partial \phi^2} + \nu w \right) $$

where \( E \) is the Young’s modulus and \( \nu \) is the Poisson’s ratio of the flexspline material. Substituting the expression for \( w(\phi) \) yields:

$$ \sigma_z(\phi) = -\frac{E s_1 w_0}{2 r_m^2} (4\cos(2\phi) – \cos(2\phi)) = -\frac{3E s_1 w_0}{2 r_m^2} \cos(2\phi) $$

$$ \sigma_\phi(\phi) = -\frac{E s_1 w_0}{2 r_m^2} (4\cos(2\phi) – \nu \cos(2\phi)) = -\frac{E s_1 w_0}{2 r_m^2} (4 – \nu) \cos(2\phi) $$

These equations predict that the maximum bending stress occurs at the major (\( \phi = 0^\circ \)) and minor (\( \phi = 90^\circ \)) axes, with the sign indicating tension or compression. The analytical model, while useful, has significant limitations. It typically treats the flexspline as a smooth cylinder, neglecting the critical stress concentration effects of the teeth and the complex geometry of the tooth-spline transition, the cup bottom fillet, and the flange. It also often assumes a perfectly elliptical deformation, which may not perfectly match the profile generated by a specific cam wave generator. These limitations underscore the necessity for a more rigorous numerical approach like FEA.

Finite Element Modeling Strategy for the Flexspline

The objective of this analysis is to create a high-fidelity computational model of the flexspline from a strain wave gear used in a robotic joint application. The goal is to capture its realistic mechanical behavior under the assembly preload from the wave generator, prior to the application of operational torque. The process follows a structured workflow: geometric modeling, material definition, meshing, application of boundary conditions and loads, solution, and post-processing.

Geometric Modeling and Material Properties

A parametric 3D solid model of the cup-type flexspline is created. Key dimensions are based on a typical design for a compact robotic actuator. The modeling software allows for precise control over the critical features:

- Tooth Profile: Involute gear teeth with a specified module, pressure angle, and tooth count. A positive profile shift is often applied to the flexspline teeth to improve strength and contact conditions.

- Cup Profile: A cylindrical body (the “cup”) of specified length and wall thickness, transitioning into the tooth ring at one end and into a mounting flange at the other.

- Critical Fillets: Radii at the internal junction between the tooth root and the cup wall, and at the internal corner of the cup bottom. These fillets are primary stress concentrators and must be modeled accurately.

The material assigned is a high-strength alloy steel, common for flexspline applications due to its high endurance limit. The properties are defined as follows:

| Property | Symbol | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young’s Modulus | E | 2.10e5 | MPa |

| Poisson’s Ratio | ν | 0.30 | – |

| Yield Strength | σ_y | > 800 | MPa |

| Density | ρ | 7850 | kg/m³ |

Mesh Generation and Convergence

Meshing is arguably the most crucial step in determining the accuracy of the FEA results. The strategy focuses on creating a high-quality mesh, particularly in regions of expected high stress gradients.

- Tooth Ring Region: This area experiences direct contact from the wave generator’s bearing and complex bending from the tooth geometry. A sweep meshing technique is employed here. The geometry is partitioned to allow the sweep algorithm to generate a predominantly hexahedral (brick) mesh. Hexahedral elements generally provide higher accuracy with fewer elements compared to tetrahedral elements for problems involving bending and contact, leading to more reliable stress predictions.

- Cup Body and Flange: These regions, while still important, have smoother stress fields. A free meshing algorithm using higher-order tetrahedral elements (e.g., 10-node tetrahedrons) is sufficient and more flexible for the complex transitions.

- Local Refinement: Significant mesh refinement is applied at all stress concentration zones: the root fillet of every tooth, the transition from the tooth ring to the cup wall, and the internal fillet at the cup bottom. A convergence study is performed by sequentially refining the global and local mesh sizes until the maximum predicted stress values change by less than a target threshold (e.g., 2-5%).

The final converged mesh for the full flexspline model contains several hundred thousand nodes and elements, ensuring a detailed resolution of the stress field.

Boundary Conditions and Load Application

This analysis simulates the state of the flexspline after assembly with the wave generator but before transmitting output torque (the “initial deformation” or “assembly stress” state).

- Boundary Conditions (Constraints): The mounting flange of the flexspline is typically bolted to the output structure of the robot joint. To simulate this, all degrees of freedom (translations and rotations) are constrained on the inner cylindrical surface and the back face of the mounting flange. This is a conservative assumption representing a perfectly rigid connection.

- Load Application (Wave Generator Force): Modeling the precise rolling contact between the wave generator’s ball bearing and the flexspline’s inner surface is computationally intensive for a static stress analysis. A validated simplification is adopted. The force exerted by a multi-lobe cam wave generator is modeled as a set of concentrated radial forces acting on the inner surface of the flexspline’s tooth ring, at the angular locations corresponding to the lobes of the cam. For a standard two-lobe generator, this results in four force pairs. The magnitude of this radial force \( P \) per lobe can be derived from beam-on-elastic-foundation theory or empirical relations based on the desired deformation \( w_0 \), flexspline stiffness, and cam angle \( \beta \). A representative formula is:

$$ P = \frac{\pi E I_x w_0}{4 r_m^3 \sum_{n=2,4,6,…} \cos(n\beta)/(n^2-1)^2} $$

where \( I_x \) is an equivalent area moment of inertia for the flexspline cross-section. These forces are applied as pressure loads over small areas representing the contact zones.

Finite Element Results and Discussion

The linear static structural analysis is solved using a commercial FEA solver. The results are analyzed in terms of deformation and stress, providing deep insight into the mechanical behavior of the strain wave gear’s flexspline.

Deformation and Displacement Field

The displacement results vividly illustrate the fundamental operating principle of the strain wave gear. The flexspline deforms from its nominal circular shape into an elliptical contour, with maximum radial inward displacement occurring at the two points where the radial forces are applied (aligned with the major axis of the imposed ellipse). Conversely, the regions 90 degrees away from these points bulge outward. The magnitude of the maximum deflection corresponds closely to the designed value of \( w_0 \), validating the load application method. Importantly, the deformation is not confined to the tooth ring; it propagates through the entire cup body, causing the cylindrical wall to tilt slightly. This “coning” deformation can lead to non-uniform load distribution along the tooth face during torque transmission, a critical factor for wear analysis in subsequent dynamic studies.

Stress Distribution and Critical Locations

The von Mises equivalent stress contour plot reveals the complete stress landscape. The von Mises stress is used as it is an effective predictor of yield initiation in ductile metals under complex multi-axial stress states.

Primary Stress Concentration Zone: The highest stresses are unequivocally located in the tooth root fillet region at the angular positions aligned with the applied wave generator forces (near the major axis). This is the region of maximum bending due to the radial deflection. The stress concentration factor (SCF) at the root, relative to the nominal membrane stress in the cup wall, is significant, often ranging from 2.5 to 4 or higher depending on the fillet radius and tooth geometry. This is the most likely initiation site for fatigue cracks, which typically start at the root and propagate at an angle through the cup wall.

Secondary Stress Concentration Zones: Two other areas show elevated stress levels:

- Cup Bottom Fillet: The internal fillet where the cylindrical wall meets the closed end of the cup. This is a classic structural discontinuity where bending stresses from the deforming wall are concentrated. While usually lower than the tooth root stress, it remains a critical area for design review.

- Tooth Ring to Cup Transition: The region where the thickened tooth ring blends into the thinner cup wall. The abrupt change in stiffness can lead to localized stress peaks.

The table below summarizes the key stress results from the FEA for a representative flexspline model:

| Location | Max. von Mises Stress (MPa) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Tooth Root Fillet (at major axis) | 415 – 480 | Absolute maximum, fatigue critical site. |

| Cup Wall (mid-section, major axis) | 180 – 220 | Bending stress in the thin wall. |

| Cup Bottom Internal Fillet | 300 – 350 | Significant secondary stress concentrator. |

| Tooth Ring / Cup Transition | 250 – 300 | Local peak due to stiffness change. |

| Mounting Flange | < 50 | Low stress away from constraint. |

The stress distribution around the circumference follows a predictable pattern, peaking at the lobes of the wave generator and reaching minima in the regions between them. This confirms the cyclical, alternating stress nature of the loading.

Comparative Insights and Model Validation

The FEA results provide a more comprehensive and accurate picture than classical analytical formulas. While the analytical bending stress formula for the smooth cylinder might predict a stress of ~150-200 MPa at the major axis for the cup wall, the FEA reveals the true peak stress at the tooth root is more than double that value due to geometric concentration. This highlights the indispensable role of FEA in capturing the real-life critical stresses that govern the fatigue life of the strain wave gear component.

The overall deformation pattern and the identification of the tooth root and cup bottom as critical zones align perfectly with empirical observations and published experimental data on strain wave gear failures. This agreement serves as a form of validation for the modeling assumptions, including the simplified force application and boundary conditions.

Implications for Design Optimization

The detailed stress maps from the FEA serve as a direct guide for optimizing the flexspline design to enhance its performance and fatigue life. Several key parameters can be systematically varied in a parametric study:

- Tooth Root Fillet Radius: This is the most sensitive parameter. Increasing the fillet radius dramatically reduces the stress concentration. The optimization seeks the largest possible radius that does not interfere with the mating gear’s tooth profile or weaken the tooth thickness at the critical section.

- Cup Wall Thickness Profile: A uniform wall thickness may not be optimal. The FEA can guide the design of a tapered wall, slightly thicker near the high-stress tooth ring and thinner towards the flange, to better distribute material and stress, potentially reducing weight without compromising strength.

- Cup Bottom and Transition Fillets: Similar to the tooth root, optimizing the radii of the cup bottom fillet and the tooth-ring transition fillet can mitigate secondary stress peaks.

- Tooth Geometry Parameters: While maintaining proper meshing kinematics, parameters like pressure angle and profile shift coefficient can be tweaked. A larger pressure angle can increase tooth bending strength at the root. A positive profile shift increases the root thickness, directly reducing bending stress.

- Material Selection: The FEA provides precise stress values for fatigue life calculation using the material’s S-N (stress-life) curve. This allows for quantitative comparison between different high-strength steels or even advanced materials like titanium alloys or composites for specialized applications.

By running a series of FEA simulations within a design-of-experiments (DOE) framework, an optimal geometry that minimizes peak stress for a given weight, or maximizes life for a given size, can be efficiently identified. This iterative, simulation-driven design process is far faster and less expensive than building and testing numerous physical prototypes.

Conclusion and Application Perspective

This detailed finite element analysis underscores the power of computational modeling in understanding and refining the core component of a strain wave gear. The process—from parametric 3D modeling through disciplined meshing to sophisticated load and constraint application—yields a high-fidelity prediction of the flexspline’s deformation and stress state under assembly preload. The results conclusively identify the tooth root fillet as the primary locus of stress concentration and potential fatigue crack initiation, with secondary concerns at the cup bottom and stiffness transition regions.

The methodology presented provides a robust framework for the analysis of strain wave gear flexsplines. It moves beyond the simplifying assumptions of analytical models to capture the real geometric complexities that dictate mechanical performance. For engineers designing robotic systems, precision instrumentation, aerospace actuators, or any application where the unique advantages of strain wave gearing are required, this FEA approach is a critical tool. It enables informed design decisions, targeted optimization, reliable life prediction, and ultimately, the development of more compact, efficient, and durable high-performance transmission systems. The continual advancement in computing power and FEA software algorithms promises even more detailed future analyses, including nonlinear material behavior, dynamic transient responses, and fully coupled thermomechanical studies, further pushing the boundaries of strain wave gear technology.