In the realm of precision mechanical transmissions, I have dedicated significant attention to the study of strain wave gears, also known as harmonic drives. This unique transmission technology relies on controlled elastic deformation to achieve motion transfer, offering a paradigm shift from traditional gear systems. Throughout my research, I have observed that strain wave gears exhibit exceptional characteristics: compact structure, lightweight design, extensive transmission ratio range, high precision, substantial load capacity, minimal backlash (often approaching zero), a high number of simultaneously engaged teeth, and the ability to transmit motion and power into sealed spaces. Over recent decades, as applications for strain wave gears have expanded across industries, the investigation of their meshing theory and novel tooth profiles has become a focal point for researchers worldwide, yielding numerous advancements. This article synthesizes my perspective on the historical development, comparative analysis, and future directions of tooth profiles in strain wave gearing, emphasizing the critical role of innovative geometries in enhancing performance.

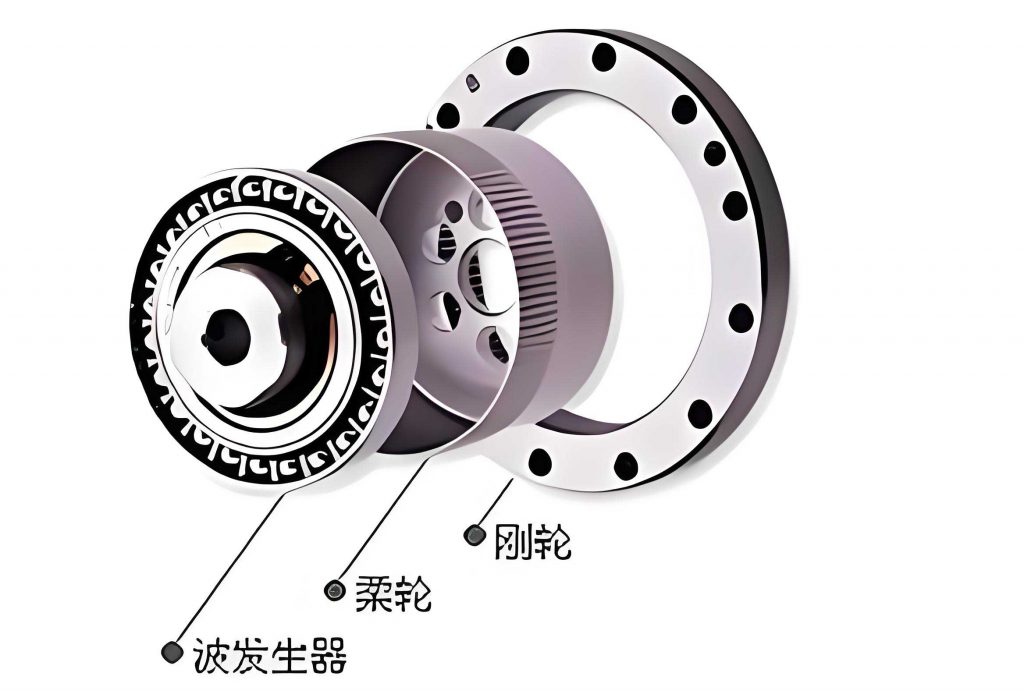

The fundamental operating principle of a strain wave gear involves three primary components: a rigid circular spline (often the fixed ring gear), a flexible spline (the deformable ring gear, typically the output), and a wave generator (which induces controlled deflection). The wave generator, usually an elliptical cam or multi-roller assembly, deforms the flexible spline into a non-circular shape, causing its teeth to engage with those of the rigid circular spline at two diametrically opposite regions. As the wave generator rotates, the engagement zones move, resulting in incremental relative motion between the flexible and rigid splines. The kinematic relationship defining the gear reduction ratio is given by:

$$ i = \frac{N_f}{N_f – N_r} $$

where \( i \) is the reduction ratio, \( N_f \) is the number of teeth on the flexible spline, and \( N_r \) is the number of teeth on the rigid circular spline. The radial displacement \( \rho(\phi) \) of the flexible spline neutral line under the influence of an elliptical wave generator can often be approximated as:

$$ \rho(\phi) = r_0 + w_0 \cos(2\phi) $$

Here, \( r_0 \) is the nominal radius of the undeformed flexible spline, \( w_0 \) is the radial deformation amplitude (a key design parameter influencing meshing quality and stress), and \( \phi \) is the angular coordinate. This elastic deformation foundation is what distinguishes strain wave gearing and imposes unique requirements on tooth profile design to ensure smooth, continuous, and efficient power transmission under load.

My analysis begins with the historically prevalent involute tooth profile. In strain wave gears, involute profiles have been extensively developed and can be categorized into two subtypes: narrow-slot teeth (where the slot width along the root circle is significantly less than the tooth thickness) and wide-slot teeth (where the slot width is comparable to or greater than the tooth thickness, effectively a modified profile with reduced tooth height to lower root stress). The parametric equations for a standard involute curve, used as a basis, are:

$$ x(\theta) = r_b (\cos \theta + \theta \sin \theta) $$

$$ y(\theta) = r_b (\sin \theta – \theta \cos \theta) $$

where \( r_b \) is the base circle radius and \( \theta \) is the roll angle. Theoretical and experimental studies I have reviewed indicate that under no-load conditions, only a limited number of tooth pairs are in simultaneous contact for both narrow and wide-slot involute profiles. When transmitting nominal torque, the number of contacting pairs increases significantly due to elastic deformation, but many teeth experience edge contact or point contact. This edge contact is detrimental as it hinders the formation of lubricant films and concentrates stress. Therefore, by the 1990s, the prevailing approach involved modifying the involute profile through tip and root relief or other corrections to improve contact patterns. However, I must note that claiming the involute profile as the ideal tooth form for strain wave gears lacks rigorous theoretical proof. The motion trajectory of the flexible spline teeth and the inherent characteristics of the involute dictate that proper meshing occurs only within a limited local region when unloaded. The celebrated multi-tooth engagement under load is largely achieved through elastic deformation-induced point contacts, which can compromise durability and load distribution. A summary of involute profile characteristics in strain wave gears is presented in Table 1.

| Profile Type | Key Advantages | Major Drawbacks | Typical Applications | Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow-Slot Involute | Manufacturing ease, wide tool availability, predictable performance. | Limited simultaneous contact unloaded, edge contact under load, stress concentration. | General-purpose industrial drives, early robotic joints. | Requires profile modification (relief) for improved contact. |

| Wide-Slot Involute (Modified) | Reduced tooth root stress, slightly better load sharing after deformation. | Reduced tooth strength potential, complex modification design. | Applications prioritizing fatigue life over peak torque. | Optimization of tooth height and relief parameters critical. |

The pursuit of a profile that ensures continuous contact in the meshing zone without relying solely on load-induced deformation led to the development of the S-shaped tooth profile. I first encountered this innovation in patents and papers from Japanese researchers in the late 1980s. The core idea was to generate a tooth profile based on the curve-mapping method, using the motion trajectory of the flexible spline tooth tip relative to the rigid circular spline as a基准曲线. The inventors aimed to eliminate the啮合 discontinuity observed in traditional profiles. Later refinements resulted in a profile composed of two circular arcs near the tip and root regions with larger radii, connected by a distinctive S-curve central portion. The mathematical formulation for generating such a profile often starts from the relative motion path. If the position vector of a point on the flexible spline tooth relative to the rigid spline is \( \vec{R}(\phi) \), derived from the deformation function \( \rho(\phi) \) and kinematic constraints, a conjugate profile can be sought. For instance, one proposed form uses a parametric curve defined by piecewise functions. Let \( u \) be a parameter along the tooth height. A simplified representation for one flank might be:

$$ X(u) = \int_{0}^{u} \cos(\psi(s)) \, ds $$

$$ Y(u) = \int_{0}^{u} \sin(\psi(s)) \, ds $$

where \( \psi(s) \) is a smoothly varying function designed to match the envelope of relative motion. Proponents demonstrated that strain wave gears employing S-shaped teeth showed improved meshing characteristics, higher rated load capacity, and reduced sensitivity to alignment errors compared to involute designs. However, in my assessment, the theoretical foundation had limitations. The profile generation often assumed a rack-and-pinion equivalence valid only for high tooth counts, introducing errors for gears with fewer teeth. Furthermore, it accepted prior kinematic models without critical re-evaluation. Thus, while S-shaped teeth marked a significant breakthrough, their status as the ultimate strain wave gear tooth profile remained debatable, warranting deeper investigation into their universal applicability and optimization.

Parallel developments in the former Soviet Union and later Japan focused on circular-arc tooth profiles. I find this approach particularly interesting because the approximate trochoidal path of the flexible spline tooth relative to the fixed rigid spline suggests that the rigid spline tooth should have a convex shape, and the conjugate flexible spline tooth profile becomes a concave circular arc or a combination of arcs. Initially, researchers proposed double-circular-arc profiles for the flexible spline paired with convex circular-arc profiles for the rigid spline. Although not strictly conjugate in a classical sense, these profiles proved highly effective in practice. The primary types implemented are single-circular-arc, common-tangent double-circular-arc, and stepped double-circular-arc profiles. For a circular arc, the profile equation is straightforward. For a flank with radius \( R \) and center coordinates \( (x_c, y_c) \), the points satisfy:

$$ (x – x_c)^2 + (y – y_c)^2 = R^2 $$

within a defined angular span. The design challenge lies in selecting the arc radii, center positions, and pressure angles to maximize the contact ratio and minimize sliding friction. My review indicates that circular-arc profiles significantly increase the number of teeth in simultaneous contact, distribute backlash more uniformly, enhance motion accuracy, and improve the fatigue strength of the flexible spline. Japanese manufacturers have successfully mass-produced strain wave gears with circular-arc teeth for robotics, where high torsional stiffness is crucial. However, a significant hurdle is tooling: machining these profiles requires special cutters with complex shapes, increasing cost. A proposed alternative, sometimes called a cycloidal or modified profile, approximates the circular arc with straight-sided cutting edges for easier manufacturing but still involves more complex tool geometry than standard involute cutters. The choice of wave generator type (elliptical cam vs. multi-roller) also influences the optimal arc parameters, necessitating region-specific tool development. Table 2 contrasts the key features of S-shaped and circular-arc profiles against the baseline involute.

| Profile Type | Development Origin | Mechanism & Aim | Performance Advantages | Manufacturing & Practical Challenges | Typical Wave Generator Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-Shaped Tooth | Japan (1980s-90s) | Curve-mapping from motion trajectory to ensure continuous contact without load deformation. | Improved meshing smoothness, higher load capacity, reduced sensitivity to misalignment. | Theoretical basis limited for low tooth counts; precise grinding required. | Primarily elliptical cam. |

| Circular-Arc (Double Arc) | Soviet Union/Japan (1970s onward) | Approximate conjugate action based on trochoidal motion; convex-concave arc pairing. | High simultaneous contact ratio, uniform backlash, enhanced stiffness and fatigue life. | Specialized, expensive cutting tools; tool geometry depends on deformation angle (φ). | Both elliptical cam and multi-roller (specific designs). |

| Involute (Baseline) | Widely adopted historically | Leverages standard gear theory; modified for elastic deformation conditions. | Familiar design process, readily available tooling, predictable. | Edge contact under load, requires modification for performance. | Universal. |

The evolution of tooth profiles is not merely academic; it has profound implications for advanced technological applications. In my work, I have seen a growing demand for high-performance strain wave gears in aerospace, robotics, and precision instrumentation. For instance, in space technology, strain wave gears are employed in satellite antenna deployment mechanisms, solar array drive assemblies, and robotic manipulators for space stations or lunar rovers. The requirements here are extreme: minimal weight, ultra-high reliability, vacuum compatibility, and ability to withstand thermal cycling. Novel tooth profiles, particularly circular-arc variants, contribute directly to meeting these demands by increasing torsional stiffness, reducing backlash (critical for positioning accuracy), and improving efficiency. A notable example is the development of short-flexspline strain wave gears with new tooth profiles (like double circular arcs) that reduce axial dimensions and weight while boosting load capacity and stiffness, making them suitable replacements for traditional designs and imported units. The technical specifications often targeted include: backlash ≤ 2 arcminutes, transmission error ≤ 2 arcminutes, efficiency ≥ 80% under rated conditions, with all structural and performance metrics matching international standards.

To quantify the design trade-offs and performance enhancements offered by new profiles, I often rely on analytical models and optimization criteria. One can formulate an optimization problem to maximize a composite performance index \( \Pi \) for a strain wave gear tooth profile:

$$ \Pi = w_1 \cdot \frac{C}{C_0} + w_2 \cdot \frac{\eta}{\eta_0} + w_3 \cdot \frac{K}{K_0} – w_4 \cdot \frac{\sigma_{max}}{\sigma_{0}} $$

where \( C \) is the load capacity, \( \eta \) is the transmission efficiency, \( K \) is the torsional stiffness, and \( \sigma_{max} \) is the maximum tooth root stress. The subscript \( _0 \) denotes a reference value (e.g., from a baseline involute design), and \( w_i \) are weighting factors reflecting application priorities. The parameters of the tooth profile (e.g., pressure angle \( \alpha \), addendum coefficient \( h_a^* \), arc radii, etc.) become design variables. Constraints include geometric non-interference, manufacturing limits, and minimum contact ratio. The contact ratio \( m_c \) for a strain wave gear, considering elastic deformation, can be approximated by:

$$ m_c \approx \frac{\Delta \phi_{engage}}{\pi / N_f} $$

where \( \Delta \phi_{engage} \) is the angular span over which teeth remain in contact, derived from the deformation kinematics and tooth flank geometry. For circular-arc profiles, this span is typically larger than for involute profiles under similar conditions.

Another critical aspect is the analysis of stresses in the flexible spline. The complex stress state results from combined bending due to wave generator deformation, tensile stress from transmitted torque, and contact stresses at the tooth flanks. Using thin-shell theory, the membrane stress \( \sigma_m \) and bending stress \( \sigma_b \) in the flexspline cylinder can be estimated. For a cylindrical shell of thickness \( t \) under radial pressure \( p(\phi) \) varying with angle, the bending moment \( M(\phi) \) per unit length is related to the radial displacement \( w(\phi) \):

$$ D \frac{d^4 w}{d\phi^4} + \frac{E t}{r_0^2} w = p(\phi) $$

where \( D = \frac{E t^3}{12(1-\nu^2)} \) is the flexural rigidity, \( E \) is Young’s modulus, and \( \nu \) is Poisson’s ratio. The tooth root bending stress is often the limiting factor for fatigue life and can be assessed using a cantilever beam model modified for the curved geometry. The choice of tooth profile directly influences the load distribution among teeth, thereby affecting the local contact pressure \( p_c \) according to Hertzian contact theory for curved surfaces. For two cylindrical surfaces in line contact, the maximum contact pressure is:

$$ p_{max} = \sqrt{\frac{F E^*}{\pi R^* L}} $$

where \( F \) is the normal load per unit length, \( \frac{1}{E^*} = \frac{1-\nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1-\nu_2^2}{E_2} \), and \( \frac{1}{R^*} = \frac{1}{R_1} \pm \frac{1}{R_2} \) (sign depending on convex/concave pairing). Optimized tooth profiles aim to reduce \( p_{max} \) by increasing the effective contact length and conformality.

The manufacturing processes for these advanced tooth profiles present their own set of challenges, which I have studied extensively. For involute teeth, standard hobbing or shaping suffice, often followed by finishing processes like honing. For S-shaped and circular-arc teeth, specialized CNC grinding or skiving is typically required. The tool profile must accurately match the desired tooth space geometry. In some cases, a generating process using a custom-shaped cutter on a modified gear hobbing machine can be employed. The economic viability often depends on production volume. For high-volume applications like robotics, investment in custom tooling for circular-arc strain wave gears is justified by the performance gains. For low-volume or prototyping, wire electrical discharge machining (EDM) might be used to form the teeth directly on the flexspline blank. Table 3 outlines common manufacturing methods for different strain wave gear tooth profiles.

| Tooth Profile Type | Primary Machining Method for Flexspline | Tooling Complexity | Secondary Finishing | Suitability for Mass Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involute (standard) | Hobbing, Shaping | Low (standard gear cutters) | Honing, Grinding (optional) | Excellent |

| Involute (modified) | CNC Hobbing with modified program | Medium | Profile grinding for high precision | |

| S-Shaped | CNC Profile Grinding, Form Milling | High (custom form wheel/mill) | Lapping, Superfinishing | Moderate (requires precision setup) |

| Circular-Arc (Double Arc) | Special Hobbing with shaped cutter, CNC Grinding | Very High (cutter geometry specific to deformation angle) | Precision grinding essential | Good for dedicated high-volume lines |

Looking forward, I believe the research and development of novel tooth profiles for strain wave gears are of paramount importance. The驱动 forces include the relentless demand for higher power density, greater precision, longer service life, and miniaturization in fields like collaborative robotics, aerospace actuators, and medical devices. Future work should focus on several key areas. First, the development of comprehensive digital twins and multi-physics simulation models that integrate finite element analysis (FEA) for stress and deformation, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) for lubrication, and multi-body dynamics for system-level performance. These models can accelerate the design optimization of tooth profiles tailored for specific operating conditions. Second, the exploration of non-standard deformation waves. While elliptical wave generators are common, multi-lobed (e.g., three-lobe) generators or contoured cam profiles could be paired with custom tooth profiles to achieve even more favorable contact patterns and load distribution. The kinematic equations would then involve higher-order harmonics:

$$ \rho(\phi) = r_0 + \sum_{n=2}^{N} w_n \cos(n\phi + \delta_n) $$

Third, the integration of advanced materials and surface engineering. The use of high-strength steels, titanium alloys, or even composites for the flexspline, combined with coatings like diamond-like carbon (DLC) on tooth flanks, can push the performance limits. The tooth profile design must account for the specific elastic properties and wear characteristics of these materials. Fourth, standardization efforts. While proprietary profiles exist, industry-wide standards for certain high-performance profiles (like a specific double-circular-arc geometry for robotics) could reduce costs and foster broader adoption. Finally, experimental validation remains crucial. Advanced testing rigs capable of measuring transmission error under load, tooth-by-tooth load sharing, temperature rise, and long-term wear are essential to validate theoretical predictions and simulation results.

In conclusion, my extensive review of the research and development trajectory of tooth profiles in strain wave gearing reveals a dynamic field driven by the quest for optimal performance. From the widespread but limited involute to the innovative S-shaped and circular-arc profiles, each step has contributed to understanding how to harness elastic deformation for efficient power transmission. The strain wave gear, with its unique operating principle, continues to offer challenges and opportunities for mechanical designers. The adoption of new tooth profiles has already proven beneficial in demanding applications like aerospace and robotics, where weight, stiffness, precision, and reliability are non-negotiable. As a researcher in this domain, I am convinced that continued investment in theoretical modeling, manufacturing technology, and experimental investigation of novel tooth geometries will unlock further potential for strain wave gears, solidifying their role as a key enabling technology in precision motion systems of the future.