In the pursuit of higher precision and efficiency in modern automation and advanced manufacturing systems, electric actuators have emerged as superior alternatives to traditional hydraulic and pneumatic cylinders. Their core advantages stem from the direct integration of a servo motor with a screw drive mechanism, enabling precise control over speed, position, and force. Among these electromechanical systems, actuators utilizing a planetary roller screw mechanism represent a significant technological advancement. This essay provides a detailed, first-person perspective analysis of the factors influencing the accuracy of such actuators, with a primary focus on deriving a comprehensive system stiffness function. The analysis incorporates numerical evaluation and emphasizes the critical role of the planetary roller screw assembly’s contact characteristics.

The fundamental advantage of an electric cylinder lies in its conversion of the servo motor’s rotary motion into precise linear motion. The planetary roller screw is pivotal to this conversion. Compared to conventional ball screws, the planetary roller screw offers higher load capacity, better stiffness, and longer life due to its multi-threaded, line-contact design. When such an actuator is employed as a motion strut in high-precision machine tools, its inherent mechanical accuracy becomes a non-negligible component of the overall system error budget. Therefore, a thorough understanding and quantification of its compliance under load is essential.

Introduction to Planetary Roller Screw Electric Actuators

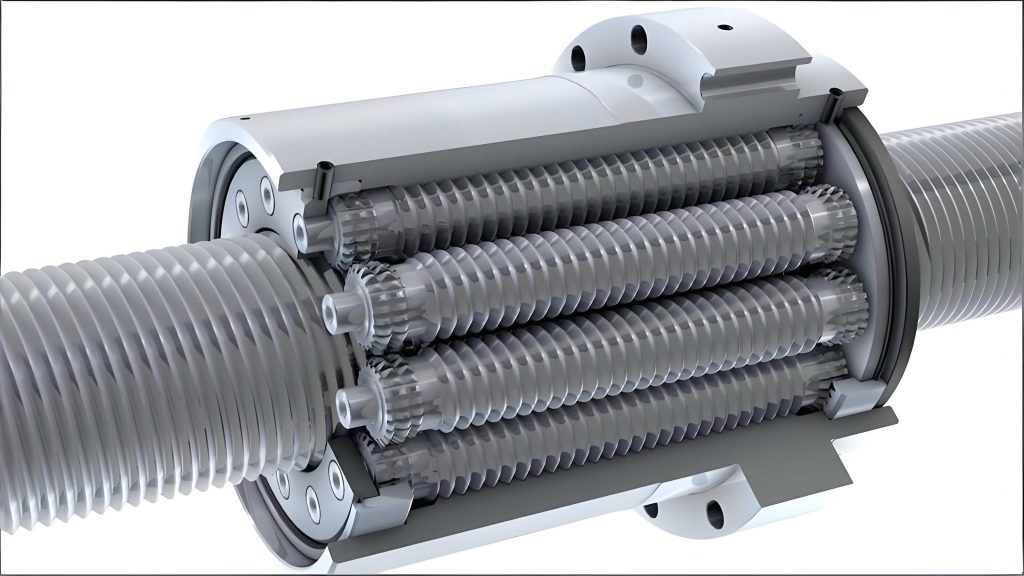

The typical structure of an electric cylinder based on a planetary roller screw involves a servo motor (often coupled via a synchronous belt or directly) that drives the central screw. The rotation of this screw is transmitted to a set of planetary rollers arranged circumferentially within a nut assembly. The rollers, meshing with both the screw and the nut threads, convert the screw’s rotation into linear translation of the nut or the screw itself, depending on the configuration. The kinematic relationship is governed by the screw’s lead and the contact geometry of the threads. This multi-contact-point design is what grants the planetary roller screw its superior performance characteristics, but it also introduces a complex set of compliances that must be analyzed collectively.

Stiffness Modeling and Accuracy Analysis

The total axial deformation, $\Delta L_{total}$, of an electric actuator under an external axial load, $F$, is the sum of several independent deformation components arising from its constituent parts. Each component contributes to the overall system compliance $K_{sys} = F / \Delta L_{total}$. A lower compliance (higher stiffness) translates directly into higher positional accuracy under varying loads.

1. Axial Displacement of Screw Support Bearings

The bearings supporting the screw shaft, typically preloaded tapered roller bearings, exhibit nonlinear axial stiffness. For bearings with line contact in both raceways, the axial displacement under load $F$ and preload $F_{a0}$ can be approximated by:

$$\Delta L_1 = \frac{F}{29.011 Z^{0.9} l_1^{0.8} \sin^{1.9}\alpha \; F_{a0}^{0.1}}$$

where $Z$ is the number of rollers, $l_1$ is the effective roller length, and $\alpha$ is the loaded contact angle. This component forms the first series compliance in the load path.

2. Contact Deformation in the Planetary Roller Screw Assembly

This is often the most significant compliance in the system. The load $F$ is distributed among the $i$ planetary rollers. Assuming ideal load sharing, the normal force on a single roller is:

$$Q = \frac{F}{i \sin\beta \cos\lambda}$$

where $\beta$ is the contact angle (typically 45°) and $\lambda$ is the screw’s lead angle.

The deformation at the two contact points—between the roller and the screw ($S$), and between the roller and the nut ($N$)—is governed by Hertzian contact theory. The key parameters are the principal curvatures at the contact points. For a standard planetary roller screw geometry:

| Contact Point | Principal Curvatures |

|---|---|

| Roller-Screw (S) | $\rho_{S11}=\rho_{S12}=\frac{2\cos\beta}{d}$, $\quad \rho_{S21}=\frac{2\cos\beta}{d_1 \cos\lambda}$, $\quad \rho_{S22}=0$ |

| Roller-Nut (N) | $\rho_{N11}=\rho_{N12}=\frac{2\cos\beta}{d}$, $\quad \rho_{N21}=-\frac{2\cos\beta}{d_2 \cos\lambda}$, $\quad \rho_{N22}=0$ |

Here, $d$ is the roller pitch diameter, $d_1$ is the screw thread effective diameter, and $d_2$ is the nut thread effective internal diameter. The total axial deflection due to contact compliance is derived from the Hertzian formulas for semi-axes and approach, resulting in a nonlinear relationship with load:

$$\Delta L_2 = (\delta_S + \delta_N) \frac{\cos\lambda}{\sin\beta} = K_{con} F^{2/3}$$

where $K_{con}$ is a constant aggregating material properties (Young’s moduli $E, E_1, E_2$ and Poisson’s ratios $\nu, \nu_1, \nu_2$), geometry, and Hertzian elliptical integral values based on the curvature sums $\sum \rho_S$ and $\sum \rho_N$.

$$K_{con} = \left( k_S + k_N \right) \left( \frac{\cos\lambda}{i^{2} \sin^{5}\beta} \right)^{1/3}$$

with

$$k_S = \left( \frac{2\mathcal{K}(e_S)}{\pi m_{aS}} \right)^{1/3} \left[ \frac{3}{8} \left( \frac{1-\nu^2}{E} + \frac{1-\nu_1^2}{E_1} \right) \right]^{2/3} \left( \sum \rho_S \right)^{-1/3}$$

and a similar expression for $k_N$. The nonlinear $F^{2/3}$ dependence is characteristic of Hertzian line/semi-elliptical contact.

3. Elastic Deformation of Screw and Nut Thread Teeth

The individual thread teeth of the screw and nut undergo complex deformation under the distributed normal load $F’ = Q \cdot i / i_1 = F / (i_1 \sin\beta \cos\lambda)$, where $i_1$ is the number of active thread turns. Modeling the teeth as short cantilever beams with specific profiles, the total deformation can be found by superimposing effects from bending, shear, root tilt, root shear, and radial expansion/contraction. For a standard trapezoidal-like thread form with geometric ratios $p=4a, a=2b, b=2c$, the screw thread deformation $\gamma_S$ is:

$$\begin{aligned}

\gamma_{S} = & \frac{3\sqrt{2}F'(1-\nu_1^2)}{16E_1}(4\ln2 – 3) + \frac{6\sqrt{2}F'(1+\nu_1)}{10E_1}\ln2 \\

& + 0 + \frac{3\sqrt{2}F'(1-\nu_1^2)}{2\pi E_1}\ln3 + \frac{\sqrt{2}F'(1-\nu_1)d_1}{4pE_1}

\end{aligned}$$

The corresponding axial displacement is simply $\Delta L_3 = \gamma_S$. A similar set of equations, with appropriate sign changes for radial expansion, yields the nut thread deformation $\gamma_N$ and its contribution $\Delta L_4 = \gamma_N$.

4. Deformation of the Nut Component Body

The nut assembly, treated as a hollow cylinder under tension/compression, deforms according to the elementary formula:

$$\Delta L_5 = \frac{F L_5}{E_2 A_2} = \frac{4F L_5}{\pi E_2 (d_2’^{\,2} – d_2^{\,2})}$$

where $L_5$ is the nut body length, $d_2’$ is its external diameter, and $A_2$ is its cross-sectional area.

5. Axial Deformation of the Loaded Screw Section

The section of the screw shaft between the support bearing and the nut is subjected to direct axial stress. Its elongation/compression is:

$$\Delta L_6 = \frac{F x}{E_1 A_1} = \frac{4F x}{\pi E_1 d_1^2}$$

where $x$ is the actuator extension length from its zero-load position. This compliance is linearly dependent on both load $F$ and extension $x$.

6. Axial Displacement due to Screw Torsion

The driving torque $T$ causes a twist in the screw shaft. The twist per unit length is $\theta = \frac{32 T}{\pi d_1^4 G}$. Since the torque is related to the axial load by $T = \frac{F p}{2\pi \eta}$, where $p$ is the screw lead and $\eta$ the mechanical efficiency, the resulting axial displacement (due to the nut “riding” on a twisted helix) is:

$$\Delta L_7 = \frac{\theta x}{2\pi} p = \frac{32 T}{\pi d_1^4 G} \frac{x p}{2\pi} = \frac{8 F p^2}{\pi^3 d_1^4 \eta G} x$$

This term also depends linearly on both $F$ and $x$.

7. Transmission Error from the Synchronous Belt Drive

Many planetary roller screw actuators use a belt drive to couple the motor. Two main error sources are considered: the polygon effect and belt elasticity. The polygon effect error from one pulley meshing is:

$$\Delta x_1 = 2\left[ R_c \phi – R_r \sin\phi – (R_p + c)\phi \right]$$

where parameters define the pulley and belt tooth geometry. The elastic stretch of the belt’s tight side (length $l_8$, width $b$, equivalent modulus $E_3$) under tight side tension $F_a = \frac{T}{r_1} + F_0$ is:

$$\Delta x_2 = \frac{F_a l_8}{E_3 b (h_s – h_t/2)}$$

Assuming negligible pulley eccentricity, the combined error reflected as an equivalent screw axial displacement is:

$$\Delta L_8 = \frac{\Delta x_1 + \Delta x_2}{2\pi r_2} p$$

where $r_2$ is the driven pulley (screw side) radius.

Total System Stiffness Function

The total axial deformation under load is the sum of all eight components:

$$\boxed{\Delta L_{total}(F, x) = \sum_{j=1}^{8} \Delta L_j(F, x)}$$

Substituting all derived expressions yields a complex stiffness function of the form:

$$\Delta L_{total} = C_1 F + C_2 F^{2/3} + C_3 F + C_4 F + C_5 F + C_6 F x + C_7 F x + C_8 F + C_9$$

where the coefficients $C_1$ through $C_9$ are constants determined by the actuator’s geometry, material properties, and preloads. The nonlinear $F^{2/3}$ term from the planetary roller screw contact is prominent. The overall compliance (inverse stiffness) is $1/K_{sys} = \partial(\Delta L_{total}) / \partial F$.

Numerical Calculation and Result Analysis

To illustrate, let’s analyze a specific planetary roller screw electric actuator with the following parameters:

| Parameter Group | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bearings | $Z$ | 16 | – |

| $l_1$ | 16 | mm | |

| $\alpha$ | 45 | ° | |

| $F_{a0}$ | 6000 | N | |

| Planetary Roller Screw | $d, d_1, d_2$ | 12, 36, 60 | mm |

| $\beta, \lambda$ | 45, 3 | ° | |

| $p$ | 5 | mm | |

| $i, i_1$ | 10, 15 | – | |

| $E, E_1, E_2$ | 200 | GPa | |

| $\nu, \nu_1, \nu_2$ | 0.27 | – | |

| Nut Body | $L_5$ | 600 | mm |

| $d_2’$ | 80 | mm | |

| Screw & Drive | $G$ | 85 | GPa |

| $\eta$ | 0.93 | – | |

| $r_1, r_2$ | 35.0, 17.5 | mm | |

| $F_0$ | 30 | N | |

| $E_3$ | 80 | GPa | |

| $l_8$ | 81.28 | mm |

Substituting these values into the complete model yields a numerical stiffness function (for deformation in mm, force in N, length in mm):

$$\Delta L_{total} \approx 2.504 \times 10^{-7}F + 2.753 \times 10^{-5}F^{2/3} + 1.106 \times 10^{-12}F + 1.365 \times 10^{-9}F + 4.915 \times 10^{-12}F x + 7.006 \times 10^{-11}F x + 5.115 \times 10^{-9}F + 5.503 \times 10^{-6}$$

The terms are ordered as per the deformation components 1 through 8. The dominance of the second term ($\propto F^{2/3}$), representing the planetary roller screw contact compliance, is immediately apparent due to its relatively large coefficient.

Evaluating the partial derivatives (force influence coefficients) at a typical operating point ($x=300$ mm, $F=5000$ N) reveals the relative sensitivity:

$$\left( \frac{\partial \Delta L_i}{\partial F} \right)^T \approx \left[ 2.50\text{e-7}, \; 1.84\text{e-5}, \; 1.11\text{e-12}, \; 1.37\text{e-9}, \; 4.92\text{e-12}x, \; 7.01\text{e-11}x, \; 5.12\text{e-9}, \; 0 \right]^T$$

At $x=300$ mm, this becomes approximately [2.50e-7, 1.84e-5, 1.11e-12, 1.37e-9, 1.48e-9, 2.10e-8, 5.12e-9, 0].

| Deformation Component | Expression ($\times 10^{-6}$ mm/N) | Relative Influence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Bearing Axial Compliance | 0.250 | ~1.3 |

| 2. PRS Contact Compliance | 18.4 | ~96.0 |

| 3. Screw Thread Flex | ~0.00011 | ~0.0006 |

| 4. Nut Thread Flex | ~0.00137 | ~0.007 |

| 5. Nut Body Tension | ~0.00148 | ~0.008 |

| 6. Screw Tension ($x$-dep.) | ~0.00210 | ~0.011 |

| 7. Screw Torsion ($x$-dep.) | ~0.00512 | ~0.027 |

| 8. Belt Error (Constant) | 0 (derivative) | 0 |

The stiffness curve $F$ vs. $\Delta L_{total}$ is not a straight line, primarily due to the $F^{2/3}$ term from the planetary roller screw contact. If this contact compliance is isolated and plotted, it shows clear nonlinearity. The collective stiffness of all other components is nearly linear but varies with actuator stroke $x$ because of the $x$-dependent terms $\Delta L_6$ and $\Delta L_7$. Therefore, the system stiffness is both load-dependent and position-dependent.

The analysis unequivocally shows that the contact stiffness within the planetary roller screw assembly and the axial stiffness of the support bearings are the most significant factors limiting the overall mechanical accuracy of the electric actuator. The bearing stiffness, while smaller than the planetary roller screw compliance, is the second-largest contributor. It is crucial to note that the planetary roller screw contact stiffness calculation assumes perfect load distribution among all rollers. In reality, manufacturing tolerances lead to uneven load sharing, especially at low loads, potentially making the effective contact compliance even higher than the ideal model predicts. This underscores the critical importance of high-precision manufacturing and selective assembly of the rollers in a planetary roller screw system.

Conclusion

The pursuit of high accuracy in electric actuators necessitates a detailed understanding of their structural compliance. This analysis systematically breaks down the primary sources of elastic deformation in a planetary roller screw-based electric cylinder. The derived total stiffness function, incorporating bearing deflection, nonlinear Hertzian contact in the planetary roller screw assembly, thread tooth bending, component stretching, torsional effects, and transmission errors, provides a comprehensive model for accuracy prediction.

The numerical evaluation highlights a key finding: the contact stiffness at the roller-screw and roller-nut interfaces is the predominant compliance, making the planetary roller screw assembly the most critical element for overall system stiffness. The support bearing stiffness is the next most significant factor. The actuator’s stiffness is not constant; it varies with both the applied load (nonlinearly) and the extension length (linearly). Therefore, for applications demanding the highest precision under varying loads and positions, such as in advanced machine tools or aerospace actuation, the design and selection process must give paramount importance to optimizing the planetary roller screw副’s contact characteristics and choosing high-stiffness support bearings. Furthermore, controlling manufacturing tolerances to ensure even load distribution among the planetary rollers is essential to achieve the theoretical stiffness performance predicted by the model.