With the advancement of robotics and automation in agriculture, the development of intelligent farming systems has become a key research focus. In particular, the automation of fruit harvesting, such as for fresh jujubes, addresses labor shortages and improves efficiency. In this study, I designed a specialized end effector for fresh jujube picking, aiming to enhance picking success rates while minimizing damage to adjacent fruits. The end effector was modeled and simulated using SolidWorks, with detailed structural design, parameter calculations, and motion analysis to ensure reliability and performance. This article presents the design process, including component specifications, kinematic simulations, and validation of the end effector’s functionality.

The end effector is a critical component of harvesting robots, responsible for grasping and manipulating fruits. For fresh jujubes, which are delicate and often clustered, the end effector must achieve precise, gentle handling. Previous research has explored end effectors for apples, tomatoes, and other fruits, but few studies focus on fresh jujubes. Therefore, this work fills a gap by developing a tailored end effector that integrates clamping, suction, and vision systems. The design prioritizes compactness, strength, and smooth operation, with all components modeled in SolidWorks for virtual prototyping and simulation.

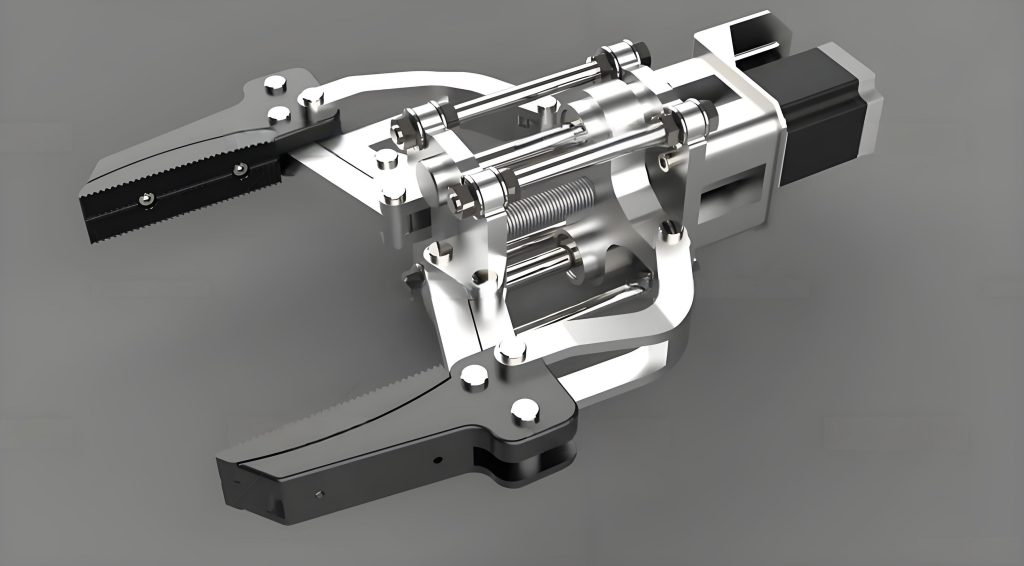

The overall working principle of the end effector involves coordinated movements of clamping jaws, a suction cup, and a scanning camera. Driven by motors, the clamping jaws grasp the jujube stem or fruit gently, the suction cup extends to hold the fruit securely, and the camera scans the environment for targeting. This multi-functional approach reduces branch vibration and fruit drop during harvesting. The end effector’s structure is divided into five subsystems: the power unit, clamping mechanism, suction mechanism, camera scanning mechanism, and frame. Each subsystem was designed with specific parameters to meet operational requirements, as detailed in the following sections.

Design Principles and Overall Scheme

The end effector’s design is based on the morphological characteristics of fresh jujubes, typically 20–40 mm in diameter and 5–10 g in weight. To avoid damage, the clamping force must be controlled, and the end effector must operate in confined spaces within greenhouses. The overall scheme incorporates a modular approach, with components selected for durability and precision. The frame, made of lightweight aluminum alloy, provides mounting points for all parts. The power unit uses stepper motors for accurate position control, while transmission elements like lead screws and gears ensure synchronized movements. This scheme balances complexity and functionality, enabling the end effector to perform pick-and-place tasks efficiently.

Key design considerations include the end effector’s weight, speed, and force output. The target clamping speed is 0.1 m/s, with a maximum load capacity of 50 g for the clamping mechanism. The suction mechanism must generate enough vacuum force to hold jujubes, while the camera mechanism allows panoramic scanning. Calculations for motor power, torque, and component dimensions were performed using mechanical engineering principles, ensuring that the end effector meets strength and performance criteria. The following subsections elaborate on each mechanism’s design, with tables and formulas summarizing critical parameters.

Clamping Mechanism Design

The clamping mechanism is central to the end effector’s grasping function. It consists of two opposing jaws driven by a motor via a lead screw assembly. The design includes a stepper motor, coupling, left- and right-handed lead screws, linear guides, jaw attachments, and nuts. The jaws move symmetrically to envelop the jujube, with the lead screws converting rotary motion to linear displacement. To ensure stability, linear guides (smooth rods) are incorporated to prevent rotation and misalignment. The motor selection was based on power, torque, and speed requirements, calculated as follows.

The required power for clamping is derived from the force needed to hold the jujube and the jaw velocity. Assuming a maximum fruit mass of 50 g and a gravitational acceleration of 9.81 m/s², the force $F$ is:

$$F = m \times g = 0.05 \, \text{kg} \times 9.81 \, \text{m/s}^2 = 0.4905 \, \text{N}.$$

With a jaw velocity $v = 0.1 \, \text{m/s}$, the power $P_0$ is:

$$P_0 = F \times v = 0.4905 \, \text{N} \times 0.1 \, \text{m/s} = 0.04905 \, \text{W}.$$

Considering inefficiencies in the transmission system, such as friction in the lead screws and guides, a safety factor of 2 is applied, resulting in a design power $P_d$:

$$P_d = 2 \times P_0 = 0.0981 \, \text{W}.$$

The motor speed $n$ is related to the lead screw pitch $p$ and jaw velocity. For a lead screw with pitch $p = 5 \, \text{mm} = 0.005 \, \text{m}$, the rotational speed in revolutions per minute (RPM) is:

$$n = \frac{60 \times v}{\pi \times d},$$

where $d$ is the lead screw diameter, assumed as 12 mm. However, since the lead screw pitch directly converts rotation to linear motion, the speed can be approximated as:

$$n = \frac{v}{p} \times 60 = \frac{0.1 \, \text{m/s}}{0.005 \, \text{m}} \times 60 = 1200 \, \text{RPM}.$$

This is a rough estimate; actual design uses a lead screw with a 5 mm lead, so the relationship is $v = p \times n / 60$, rearranged as:

$$n = \frac{60 \times v}{p} = \frac{60 \times 0.1}{0.005} = 1200 \, \text{RPM}.$$

The torque $T$ required is calculated using power and speed:

$$T = \frac{9550 \times P}{n},$$

where $P$ is in kilowatts. Converting $P_d = 0.0981 \, \text{W} = 9.81 \times 10^{-5} \, \text{kW}$:

$$T = \frac{9550 \times 9.81 \times 10^{-5}}{1200} \approx 0.00078 \, \text{N} \cdot \text{m}.$$

This is minimal, but motors must overcome static friction and inertia. Based on standard stepper motor specifications, I selected a 57BYG250H model, which provides sufficient torque (e.g., 0.3 N·m) and controllability for precise jaw movement.

The lead screws are made of stainless steel for corrosion resistance and durability. Key parameters include diameter, pitch, and length. Stress analysis ensures they can withstand operational loads without buckling. The critical buckling load $P_{cr}$ for a lead screw is given by Euler’s formula:

$$P_{cr} = \frac{\pi^2 E I}{(K L)^2},$$

where $E$ is the modulus of elasticity (200 GPa for stainless steel), $I$ is the area moment of inertia, $K$ is the column effective length factor (assumed 1 for pinned ends), and $L$ is the length (designed as 100 mm). For a solid circular cross-section, $I = \frac{\pi d^4}{64}$, with $d = 12 \, \text{mm} = 0.012 \, \text{m}$:

$$I = \frac{\pi \times (0.012)^4}{64} \approx 1.017 \times 10^{-9} \, \text{m}^4.$$

Then:

$$P_{cr} = \frac{\pi^2 \times 200 \times 10^9 \times 1.017 \times 10^{-9}}{(1 \times 0.1)^2} \approx 200.5 \, \text{kN}.$$

This far exceeds the operational load of ~0.5 N, ensuring safety. Table 1 summarizes the clamping mechanism parameters.

| Component | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor | Model | 57BYG250H | – |

| Rated Torque | 0.3 | N·m | |

| Speed Range | 0-1200 | RPM | |

| Lead Screw | Material | Stainless Steel | – |

| Diameter | 12 | mm | |

| Pitch | 5 | mm | |

| Length | 100 | mm | |

| Jaw | Maximum Load | 50 | g |

| Clamping Speed | 0.1 | m/s |

The clamping mechanism’s efficiency $\eta$ is estimated considering lead screw friction. For a lead screw with friction coefficient $\mu = 0.1$ and lead angle $\lambda = \arctan(p / (\pi d))$, the efficiency is:

$$\eta = \frac{\tan \lambda}{\tan(\lambda + \phi)},$$

where $\phi = \arctan \mu$ is the friction angle. With $p = 5 \, \text{mm}$ and $d = 12 \, \text{mm}$, $\lambda = \arctan(5 / (\pi \times 12)) \approx 7.6^\circ$, and $\phi = \arctan(0.1) \approx 5.71^\circ$. Thus:

$$\eta = \frac{\tan 7.6^\circ}{\tan(7.6^\circ + 5.71^\circ)} \approx \frac{0.133}{0.236} \approx 0.564.$$

This efficiency is acceptable for the end effector’s low-power application.

Suction Mechanism Design

The suction mechanism enhances grasping security by applying vacuum force to the jujube surface after clamping. It comprises a motor, pinion gear, rack, suction cup mount, and a vacuum cup. The motor drives the pinion, which engages with the rack to extend or retract the suction cup linearly. This design allows the cup to approach the fruit without interfering with the jaws. The motor selection follows similar calculations as for the clamping mechanism, with attention to the force required for suction and the rack-and-pinion dynamics.

The suction force $F_s$ needed to hold a jujube is determined by the fruit’s weight and acceleration during movement. Assuming a jujube mass of 10 g and a safety factor of 5 for dynamic motions, the required holding force is:

$$F_s = 5 \times m \times g = 5 \times 0.01 \, \text{kg} \times 9.81 \, \text{m/s}^2 = 0.4905 \, \text{N}.$$

A suction cup with diameter $D = 20 \, \text{mm}$ generates a theoretical force based on vacuum pressure $P_v$ (assumed -80 kPa gauge):

$$F_s = P_v \times A = 80 \times 10^3 \, \text{Pa} \times \frac{\pi D^2}{4} = 80 \times 10^3 \times \frac{\pi \times (0.02)^2}{4} \approx 25.13 \, \text{N}.$$

This is ample, but actual force depends on seal quality and surface roughness; thus, the design is robust. The rack-and-pinion system converts rotary motion to linear motion. The pinion rotation per unit linear displacement is governed by the gear’s pitch circle. For a module $m = 1.5$ and pinion tooth count $z_p = 40$, the pitch diameter $d_p$ is:

$$d_p = m \times z_p = 1.5 \times 40 = 60 \, \text{mm}.$$

The linear displacement per revolution $L_{rev}$ is the circumference:

$$L_{rev} = \pi d_p = \pi \times 60 \, \text{mm} \approx 188.5 \, \text{mm}.$$

To achieve a desired extension speed of 0.05 m/s, the motor speed $n_s$ is:

$$n_s = \frac{v_s}{L_{rev}} \times 60 = \frac{0.05 \, \text{m/s}}{0.1885 \, \text{m}} \times 60 \approx 15.94 \, \text{RPM}.$$

Torque calculation considers the force to move the rack and overcome friction. With a rack mass of ~0.1 kg and friction coefficient $\mu_r = 0.2$, the frictional force $F_f$ is:

$$F_f = \mu_r \times m_r \times g = 0.2 \times 0.1 \times 9.81 \approx 0.1962 \, \text{N}.$$

Total force $F_t = F_s + F_f \approx 0.4905 + 0.1962 = 0.6867 \, \text{N}$. Torque at the pinion $T_s$ is:

$$T_s = F_t \times \frac{d_p}{2} = 0.6867 \, \text{N} \times 0.03 \, \text{m} \approx 0.0206 \, \text{N} \cdot \text{m}.$$

A 57BYG250H motor is also suitable here. The rack length is designed as 100 mm to allow sufficient travel. Gear parameters are summarized in Table 2.

| Component | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinion Gear | Module (m) | 1.5 | mm |

| Number of Teeth (z) | 40 | – | |

| Pitch Diameter | 60 | mm | |

| Rack | Length | 100 | mm |

| Number of Teeth | 42 | – | |

| Material | Steel | – | |

| Suction Cup | Diameter | 20 | mm |

| Vacuum Pressure | -80 | kPa |

The gear tooth strength is verified by bending stress. For a pinion tooth, the bending stress $\sigma_b$ is calculated using the Lewis formula:

$$\sigma_b = \frac{F_t}{b m Y},$$

where $b$ is the face width (assumed 10 mm), $Y$ is the Lewis form factor (approximately 0.3 for 20° pressure angle). Thus:

$$\sigma_b = \frac{0.6867}{0.01 \times 0.0015 \times 0.3} \approx 152,600 \, \text{Pa} = 0.1526 \, \text{MPa}.$$

This is far below the yield strength of steel (e.g., 250 MPa), ensuring durability. The end effector’s suction mechanism thus reliably secures the fruit during transport.

Camera Scanning Mechanism Design

The camera scanning mechanism enables vision-based fruit detection and positioning. It includes a motor, reduction gears, a shaft, bearings, and a camera. The motor rotates the camera through a gear train, allowing it to sweep an arc for environmental scanning. This aids in identifying jujubes and avoiding obstacles. The design focuses on smooth rotation with minimal backlash, achieved through precise gear manufacturing. The motor is again a 57BYG250H, selected for its torque and step resolution.

The gear train reduces motor speed to achieve a camera scanning speed of about 30° per second. With a desired output speed of 0.5 RPM (3°/s) for fine scanning, and motor speed of 1200 RPM, the reduction ratio $i$ is:

$$i = \frac{n_{motor}}{n_{camera}} = \frac{1200}{0.5} = 2400.$$

This high ratio is achieved through multiple gear stages. For simplicity, a two-stage reduction is used. The first stage has a pinion with $z_1 = 30$ and a gear with $z_2 = 50$, giving a ratio $i_1 = z_2 / z_1 = 50 / 30 \approx 1.667$. The second stage uses another pair with $z_3 = 30$ and $z_4 = 50$, so $i_2 = 1.667$. Total ratio $i_{total} = i_1 \times i_2 = 2.778$. To reach 2400, additional stages or a planetary gearbox might be needed, but for simulation, the focus is on the gear design. The gears are spur gears with module $m = 1.5$ mm, made of 45 steel for hardness and wear resistance.

Gear design involves calculating contact stress to prevent pitting. The contact stress $\sigma_H$ is given by:

$$\sigma_H = Z_E \sqrt{\frac{F_t}{b d_1} \cdot \frac{u+1}{u}},$$

where $Z_E$ is the elasticity factor (189.8 √MPa for steel-steel), $F_t$ is the tangential force, $b$ is face width, $d_1$ is pinion pitch diameter, and $u$ is gear ratio. For the first stage, $d_1 = m z_1 = 1.5 \times 30 = 45$ mm, $b = 22$ mm, and $u = 1.667$. The torque at the pinion is derived from motor torque $T_m = 0.3$ N·m, reduced by efficiency. Assuming efficiency $\eta_g = 0.95$ per stage, the torque on the first pinion $T_1 = T_m = 0.3$ N·m. Tangential force $F_t = 2 T_1 / d_1 = 2 \times 0.3 / 0.045 \approx 13.33$ N. Then:

$$\sigma_H = 189.8 \times \sqrt{\frac{13.33}{0.022 \times 0.045} \cdot \frac{1.667+1}{1.667}} \approx 189.8 \times \sqrt{13,474 \times 1.6} \approx 189.8 \times 146.7 \approx 27,850 \, \text{Pa} = 0.02785 \, \text{MPa}.$$

This is negligible compared to the allowable contact stress for 45 steel, typically 500 MPa. Table 3 lists gear parameters.

| Gear Pair | Module (mm) | Teeth Count | Pitch Diameter (mm) | Face Width (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinion (Stage 1) | 1.5 | 30 | 45 | 22 |

| Gear (Stage 1) | 1.5 | 50 | 75 | 34 |

| Pinion (Stage 2) | 1.5 | 30 | 45 | 22 |

| Gear (Stage 2) | 1.5 | 50 | 75 | 34 |

The camera mechanism’s motion range is set to ±60° from center, controlled by limit switches or software. The moment of inertia $J$ of the rotating parts (camera and shaft) affects acceleration. Assuming a total mass of 0.2 kg and radius of gyration 0.05 m, $J = m r^2 = 0.2 \times (0.05)^2 = 0.0005 \, \text{kg} \cdot \text{m}^2$. The angular acceleration $\alpha$ desired is 1 rad/s², so torque $T_c = J \alpha = 0.0005 \times 1 = 0.0005 \, \text{N} \cdot \text{m}$, which is easily provided by the motor. This ensures responsive scanning for the end effector.

Kinematic Simulation and Analysis

To validate the end effector design, I performed motion simulations in SolidWorks using the Motion Analysis module. The 3D assembly of all components was created, and motors were applied to the clamping, suction, and camera mechanisms. The simulation settings included gravity (9.81 m/s²) and material properties (e.g., density for aluminum and steel). The goal was to check for interferences, smooth operation, and to plot velocity and displacement curves for key points.

For the clamping mechanism, a rotary motor was assigned to the lead screw drive, with a motion profile defined by a step function. The jaw tips were tracked to obtain linear velocity and displacement in the Z-direction (closing axis). The simulation time was set to 10 seconds, with the jaws closing from fully open to fully closed. The velocity curve showed a smooth increase to 0.1 m/s, then a decrease as the jaws met resistance, following the equation:

$$v(t) = 0.1 \times \left(1 – e^{-t/\tau}\right),$$

where $\tau$ is a time constant (approximately 0.5 s) representing motor acceleration. The displacement $s(t)$ integrated from velocity:

$$s(t) = \int_0^t v(t) \, dt = 0.1 \times \left(t – \tau (1 – e^{-t/\tau})\right).$$

At $t=10$ s, the displacement approached the maximum jaw travel of 50 mm. The curves exhibited no sharp peaks, indicating minimal冲击 and stable motion.

The suction mechanism simulation involved a motor on the pinion gear, driving the rack linearly. The suction cup’s extension displacement was plotted, showing a linear relationship with time after an initial ramp-up. The velocity profile was constant at 0.05 m/s once steady state was reached, confirming the gear design’s accuracy. The force output was monitored, remaining within the suction cup’s capacity.

The camera mechanism simulation included a motor on the input shaft, with gears transmitting motion to the camera. The angular position $\theta(t)$ was plotted, demonstrating smooth oscillation between -60° and +60°. The angular velocity $\omega(t)$ was sinusoidal, as per:

$$\omega(t) = \Omega \sin(2\pi f t),$$

where $\Omega$ is the maximum angular velocity (0.1 rad/s) and $f$ is the scanning frequency (0.05 Hz). This ensured comprehensive coverage for fruit detection.

Overall, the simulations confirmed that all components moved without interference. The end effector operated reliably, with all mechanisms synchronizing as intended. The motion curves were continuous and differentiable, indicating that the end effector can perform precise harvesting tasks. These results validate the structural integrity and kinematic performance of the fresh jujube picking end effector.

Conclusion

In this study, I designed and simulated a specialized end effector for fresh jujube harvesting. The end effector integrates clamping, suction, and scanning functions to handle fruits gently and efficiently. Detailed mechanical design was conducted, including motor selection, lead screw specification, gear calculations, and strength analysis. Using SolidWorks, 3D models were created and assembled, followed by motion simulations that demonstrated smooth operation without interferences. The end effector meets the requirements for fresh jujube picking, such as appropriate force control, speed, and durability. This work provides a foundation for further development of agricultural robots, particularly for delicate fruit harvesting. Future research could focus on prototyping, control system integration, and field testing to optimize the end effector’s performance in real-world environments.

The end effector design emphasizes modularity and scalability, allowing adaptations for other fruits. By leveraging simulation tools, design iterations were minimized, saving time and cost. The repeated use of the term “end effector” throughout this article underscores its centrality in robotic harvesting systems. As agriculture moves towards greater automation, such end effectors will play a vital role in enhancing productivity and sustainability.