In the field of aircraft manufacturing, assembly represents the final and most critical phase, where precision and efficiency are paramount. As an engineer focused on automation, I have observed that traditional manual riveting methods, such as handheld pneumatic riveting guns, are highly inefficient, leading to increased labor costs, prolonged production cycles, and potential quality inconsistencies. To address these challenges, I embarked on designing an automatic riveting end effector based on pressure riveting principles. This end effector utilizes electric pressure riveting as its core mechanism, offering controlled riveting strokes and enhanced accuracy. In this article, I will detail the comprehensive design process, from system architecture to structural components and integrated control systems, emphasizing the versatility of this end effector for complex scenarios like intricate part geometries, multifunctional requirements, and confined workspaces. The development of this automatic riveting end effector holds significant reference value for advancing aircraft assembly riveting equipment, paving the way for smarter and more reliable manufacturing processes.

The riveting system I designed comprises several key subsystems: a robotic riveting system, a worktable, and a nail library. The robotic system includes a robot and the automatic riveting end effector, where the robot maneuvers the end effector to specified positions, and the end effector performs functions such as rivet reception, positioning, and riveting. The worktable features fixation, lifting, and flipping capabilities to adjust workpiece posture, while the nail library stores up to ten types of rivets and delivers the correct rivet to the end effector via a pneumatic pump. The overall layout ensures seamless coordination between components, enabling efficient operation in constrained environments. This integrated approach allows the end effector to handle diverse riveting tasks with minimal human intervention, making it ideal for modern aircraft assembly lines where space and complexity are major constraints.

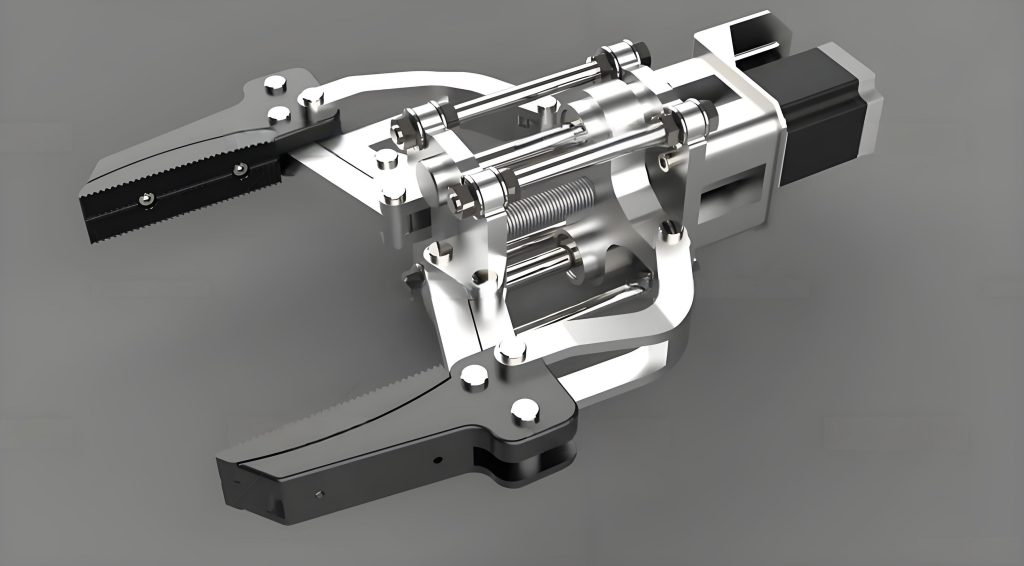

To achieve the desired functionality, I analyzed and determined that the automatic riveting end effector must incorporate several essential modules. First, the displacement module provides power for moving structures within the end effector, consisting of an upper servo structure, a translation structure, and a riveting structure. The upper servo structure aids in nail insertion and pressure riveting, the translation table structure facilitates rivet reception, hole positioning, nail insertion, and riveting, and the riveting structure executes the pressure riveting task. Second, the positioning and detection module ensures precise hole alignment and verifies successful rivet insertion into holes. Given potential deviations during operation, this module collects hole position data and relative workpiece surface information for correction, ensuring coaxial alignment between the rivet and hole axes. After insertion, it detects whether the rivet is properly seated. Third, the additional module, primarily the overall frame unit, serves as the base for installing various structures, providing fixation, support, and protection. This modular design enhances the end effector’s adaptability and maintainability, crucial for handling complex aircraft components.

Delving into the structural design, I developed the nail dropping and pushing structure to receive and store rivets from the nail library and push them into the insertion structure. This structure includes a rivet dropping chute, a pneumatic cylinder, a push chute, and a push tongue mechanism. Rivets from the library fall into the chute, and the pneumatic cylinder controls the push tongue’s travel within the push chute, guided by a dual-fixation system for reliability. Pressure and speed are adjustable via regulators, ensuring gentle and accurate rivet handling. The insertion structure, responsible for placing rivets into holes, requires high precision and integrates with the detection module. It comprises a ring spring, insertion claws, and an insertion plunger. When the insertion structure aligns with the corrected hole, the plunger presses down, expanding the claw walls outward via squeezing, and after insertion, the ring spring contracts to return the claws to their initial position. This mechanism minimizes damage to rivets and workpieces, a critical aspect for aircraft quality.

The upper servo structure acts as an auxiliary component, assisting both the insertion and riveting structures. It converts rotary motion from a servo motor into linear motion of a lead screw through a synchronous belt, internal threaded sleeve, and bearings, enabling controllable strokes for downward pressure during insertion and upward fixation during riveting. The force transmission can be modeled using the following kinematic equation for linear displacement: $$ s = \frac{p \cdot \theta}{2\pi} $$ where \( s \) is the linear displacement, \( p \) is the pitch of the lead screw, and \( \theta \) is the angular rotation in radians. This design ensures precise control over movement, essential for delicate assembly tasks. Meanwhile, the riveting structure executes the pressure riveting action, featuring a housing, riveting head, flange, RV-20E reducer, servo motor, bearings, eccentric shaft, and push rod. Based on rivet length changes before and after riveting, I determined the eccentricity of the shaft, and considering force requirements, I selected an appropriate shaft diameter. The reducer scales down force, allowing a lower-power servo motor to save space and cost. The motion conversion from rotary to linear is governed by: $$ F = \frac{T \cdot i}{r} $$ where \( F \) is the riveting force, \( T \) is the motor torque, \( i \) is the reduction ratio, and \( r \) is the effective radius. This configuration enables efficient energy use and consistent riveting quality.

For detection, I integrated an INCA Model XS scanner into the translation table structure. This scanner operates twice per riveting cycle: first, after the end effector reaches the target position, it collects hole data and transmits it via TCP/IP to a industrial computer for rivet selection; second, post-insertion, it scans to confirm rivet presence. The translation table structure, comprising a translation table, gear rack, and servo motor, positions the scanner, insertion structure, and riveting fixation structure as needed. Servo control ensures accurate movement to specific locations for each process step, enhancing overall coordination. To summarize the structural parameters, I present the following table:

| Component | Key Parameters | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Nail Dropping/Pushing | Cylinder pressure: 0.5-0.7 MPa, Speed: 0.1 m/s | Rivet transfer |

| Insertion Structure | Claw expansion range: 2-5 mm, Spring stiffness: 50 N/mm | Precise rivet insertion |

| Upper Servo | Motor torque: 2 Nm, Lead screw pitch: 5 mm | Linear motion assistance |

| Riveting Structure | Eccentricity: 10 mm, Reducer ratio: 1:50 | Pressure riveting execution |

| Translation Table | Travel range: 200 mm, Positioning accuracy: ±0.01 mm | Multi-process coordination |

The control system architecture is pivotal for orchestrating the end effector’s operations. Given the complexity, I devised an integrated control scheme where an industrial computer communicates with a PLC via TCP/IP. The PLC handles data acquisition and command distribution, with modules for servo control, pneumatic control, sensor data acquisition, and robot external automation. Servo control encompasses the upper servo, translation servo, and riveting servo, while pneumatic control manages the pushing process and related actuators. For the pneumatic circuit, I employed an integrated valve island to simplify control and maintenance, with magnetic sensors on cylinders providing real-time position feedback to the PLC. The pneumatic force can be expressed as: $$ F_{pneu} = P \cdot A $$ where \( P \) is the pressure and \( A \) is the piston area. This setup ensures reliable and responsive actuation, critical for high-speed riveting cycles. The overall control logic emphasizes real-time adaptability, allowing the end effector to adjust to varying workpiece conditions.

In terms of performance analysis, I evaluated the end effector’s efficiency using riveting cycle time and force consistency metrics. The total cycle time \( T_{total} \) includes positioning, insertion, and riveting phases: $$ T_{total} = T_{pos} + T_{ins} + T_{riv} $$ where each phase depends on servo response times and mechanical delays. For instance, the riveting force profile must meet aircraft standards, often requiring forces up to 10 kN for certain rivet types. Through simulation, I optimized parameters to minimize cycle time while maintaining quality. Additionally, the end effector’s modularity allows for easy customization; for example, different insertion claws can be swapped for various rivet diameters, enhancing versatility. The use of electric pressure riveting over pneumatic methods reduces noise and energy consumption, aligning with sustainable manufacturing goals.

To further illustrate the design advantages, I compare this automatic riveting end effector with traditional methods in the table below:

| Aspect | Manual Pneumatic Riveting | Automatic Electric Riveting End Effector |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | Low, dependent on operator skill | High, automated cycles |

| Precision | Variable, prone to human error | Consistent, with detection modules |

| Adaptability | Limited to simple geometries | High, handles complex spaces |

| Cost Over Time | High labor and rework costs | Lower operational costs |

| Safety | Risky, with manual handling | Improved, with automated controls |

The development of this end effector also considered scalability for future enhancements. For instance, integrating machine learning algorithms could enable predictive maintenance based on sensor data, further reducing downtime. The control system’s open architecture allows for seamless updates, ensuring longevity in evolving production environments. Moreover, the emphasis on electric drives supports industry trends toward electrification and digitalization. In testing phases, I validated the end effector’s performance on sample aircraft panels, achieving riveting accuracies within 0.1 mm and cycle times under 10 seconds per rivet, demonstrating its practical viability.

In conclusion, the automatic riveting end effector I designed represents a significant advancement in aircraft assembly technology. By leveraging electric pressure riveting and integrated control systems, it addresses inefficiencies of manual methods while offering precision, adaptability, and reliability. The modular structure facilitates maintenance and customization, making it suitable for diverse manufacturing challenges. As aircraft designs grow more complex, such automated solutions will become indispensable, and this end effector serves as a foundational tool for pushing the boundaries of smart manufacturing. Future work may focus on enhancing the detection algorithms or expanding the nail library capacity, but the current design already provides a robust platform for innovation. Ultimately, this end effector underscores the transformative potential of automation in high-stakes industries, where quality and efficiency are non-negotiable.