Labor scarcity presents a significant challenge to modern society. The widespread adoption of agricultural robots in farm management is replacing numerous tedious and complex tasks such as harvesting, transplanting, pruning, and spraying. Particularly in orchard operations, the rapid proliferation of agricultural robots has substantially reduced dependence on seasonal labor, enhanced fruit yield and quality, and significantly lowered production costs. A primary focus of agricultural robotics research lies in the development and application of end effectors. Many scholars dedicate their efforts to designing various types of end effectors to adapt to different agricultural tasks and diverse environmental conditions. Research has led to robotic systems for harvesting apples, small spherical fruits, and tomatoes, often employing a “grasp-cut-release” sequence. In citrus harvesting, specific robots have been designed, though they face limitations with fruits of varying sizes or very short stems, where cutting tools risk damaging the fruit. For kiwifruit, end effectors with pressure perception have been developed based on their growth characteristics.

Fruit bagging remains a critical challenge in the process of agricultural intellectualization. However, within bagging research, there is a notable lack of studies on bagging end effectors specifically designed for short-stemmed fruits. While several bagging mechanisms exist, they are primarily suitable for fruits with longer stems. For short-stemmed fruits like peaches, bagging poses a formidable challenge: the paper bag cannot be wrapped solely around the fruit stem; it must be positioned over the fruit and sealed around the supporting branch. To address this gap, we have developed a specialized bagging robot and its corresponding end effector for young peaches. The core innovation of this system is its end effector, designed to perform the complete bagging operation for short-stemmed fruit autonomously.

The primary objective of our bagging robot is to replace manual labor in performing bagging tasks for young peaches in standardized orchards. The design goals for the end effector are: 1) To ensure a success rate exceeding 95% for young peach bagging; 2) To avoid causing damage to the young fruit during the process; 3) To prevent injury to the main branch supporting the fruit; 4) To minimize the overall size and mass of the end effector to ensure flexible operation. The complete robotic system includes a mobile chassis, a bag magazine storage unit, a staple magazine storage unit, a robotic arm, the end effector, a control cabinet, depth cameras, and LiDAR. The robot navigates autonomously using LiDAR and GPS, while a vision system with depth cameras locates the fruit in 3D space. The robotic arm then positions the end effector to execute the bagging sequence.

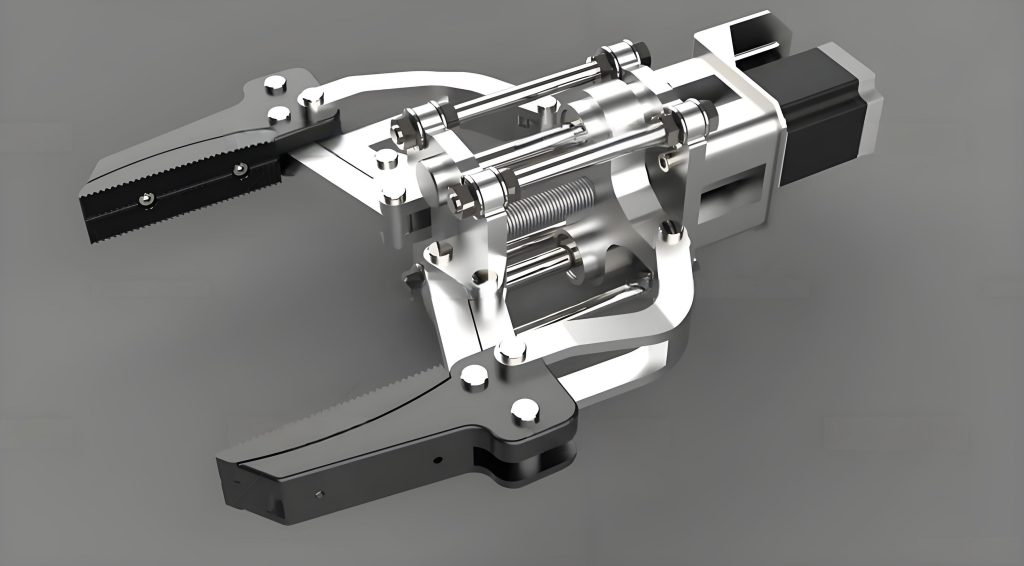

Mechanical Design and Analysis of the End Effector

The end effector is the pivotal component of the system, directly determining the success rate of the bagging task. It is mounted on the final joint of the robotic arm and must adapt to variations in fruit size, position, and orientation. Our design, informed by extensive study of peach morphology and growth patterns, accomplishes all necessary motions using a single stepper motor. The end effector integrates a compact depth camera for final fruit positioning. Its operation relies on three core subsystems: the Bag Pick-and-Transport Unit, the Bag Opening Unit, and the Sealing Unit.

1. Bag Pick-and-Transport Unit

This unit is responsible for extracting a single paper bag from the magazine and transporting it to the opening position. It features a pair of suction cups (Suction Cup Set 1) connected to Vacuum Pump 1. An auxiliary electromagnet pushes the suction assembly towards the bag stack. Once the top bag is securely adsorbed, the electromagnet retracts, and the unit is lifted by the main drive mechanism.

Motion Analysis: The vertical transport is achieved via a lead screw driven by the central stepper motor. The linear velocity \( v_{trans} \) of the unit is determined by the motor’s rotational speed \( r \) (in revolutions per second) and the screw’s lead \( i \).

$$ v_{trans} = i \cdot r $$

Given a screw lead \( i = 4 \, \text{mm/rev} \) and a motor speed \( r = 7.5 \, \text{rev/s} \) (450 rpm), the calculated transport velocity is:

$$ v_{trans} = 4 \, \text{mm/rev} \times 7.5 \, \text{rev/s} = 30 \, \text{mm/s} $$

The total travel distance \( h_{total} \) for the unit from the pick position to the open position is 126 mm. The time required for this transport phase \( t_{transport} \) is:

$$ t_{transport} = \frac{h_{total}}{v_{trans}} = \frac{126 \, \text{mm}}{30 \, \text{mm/s}} = 4.2 \, \text{s} $$

This unit includes a square push rod that interacts with the Bag Opening Unit during its upward motion, initiating the bag opening sequence.

2. Bag Opening Unit

Inspired by linkage mechanisms, this unit is designed to open the mouth of the paper bag after it has been transported. It does not have an independent power source. Instead, it is actuated by the square push rod from the Bag Pick-and-Transport Unit. The unit consists of a slider (Slider 1) that moves within a guide slot. Attached to it are two pairs of suction cups (Suction Cup Set 2) connected to Vacuum Pump 2. As the square rod pushes Slider 1 upward, a cam or linkage mechanism causes the two pairs of suction cups to move inward, gripping the two sides of the paper bag held by the first set of suction cups.

Motion Analysis: Once Vacuum Pump 1 releases the bag and Vacuum Pump 2 activates, the Bag Pick-and-Transport unit reverses direction. As it moves down a short, predetermined distance, a spring mechanism causes Slider 1 to follow. This downward motion, through the designed linkage, forces the two pairs of Suction Cup Set 2 to move apart, thereby fully opening the mouth of the bag. The opening displacement \( d_{open} \) is 10.14 mm. The time \( t_{open} \) required for this opening action, based on the same motor speed, is:

$$ t_{open} = \frac{d_{open}}{v_{trans}} = \frac{10.14 \, \text{mm}}{30 \, \text{mm/s}} \approx 0.338 \, \text{s} $$

This elegant design converts the linear motion of the main drive into the precise opening action needed, eliminating the need for a separate actuator for the end effector’s opening function.

3. Sealing Unit

The final and crucial step is sealing the bag around the branch above the fruit using a metal staple. The Sealing Unit is also mechanically coupled to the main drive and lacks its own motor. It comprises a slider mechanism (Slider 3) and two jaw assemblies. During the return stroke of the main drive, a “sealing assistant” component on the moving frame engages with Slider 3, driving it downward. This motion forces the two jaw assemblies to converge, crimping a pre-loaded staple around the neck of the bag.

Motion Analysis: The sealing action completes the final part of the main drive’s return stroke. After staple crimping, the sealing assistant component disengages automatically due to designed resistance. A return spring then resets the Sealing Unit’s jaws to their open position, ready for the next cycle. The distance for the sealing stroke \( d_{seal} \) can be derived from the total return travel and the distances allocated to other phases. If the total return stroke is also 126 mm, and portions are used for bag opening (\(d_{open}\)) and other clearances, the effective sealing stroke \( d_{seal\_eff} \) is a significant portion of that. The time for the sealing phase \( t_{seal} \) is:

$$ t_{seal} = \frac{d_{seal\_eff}}{v_{trans}} $$

Based on the system’s cycle time analysis (detailed later), the effective time for the mechanical sealing action is approximately 3.862 s. An adjustment screw allows for fine-tuning the point of staple crimping to accommodate variations in fruit and branch position.

The integration of all three subsystems onto a single, centrally-driven end effector is the key to operational efficiency. Employing multiple independent actuators would require sequential control and coordination, increasing cycle time and complexity. Our design enables the entire bagging sequence—pick, transport, open, seal, reset—to be executed with one reciprocating cycle of a single stepper motor, dramatically enhancing speed and reliability.

| Subsystem | Key Component | Actuation Method | Critical Displacement | Calculated Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bag Pick-and-Transport | Suction Cup Set 1, Lead Screw | Stepper Motor (Forward) | 126 mm (Up) | 4.200 |

| Bag Opening | Suction Cup Set 2, Linkage | Driven by Main Return Stroke | 10.14 mm (Open) | 0.338 |

| Sealing | Jaw Assemblies, Staple | Driven by Main Return Stroke | ~115.86 mm (Effective) | ~3.862 |

| Total Mechanical Motion Time | ~8.400 | |||

Control Sequence and Cycle Time Analysis

The end effector’s control is managed by a microcontroller (e.g., Arduino UNO R3), which coordinates the stepper motor, the two vacuum pumps, and the electromagnet according to a precise sequence. The following flowchart and analysis detail the control logic and the temporal breakdown for bagging a single peach.

Control Sequence:

- t0 (0 s): System starts. Vacuum Pump 1 is activated.

- t1 (1 s): Electromagnet is energized, pushing Suction Cup Set 1 to contact the paper bag stack. The 1-second delay ensures Vacuum Pump 1 reaches sufficient suction force.

- t2 (4 s): The bag is securely adsorbed. Electromagnet is de-energized, retracting the suction head and extracting the bag from the magazine. The 3-second duration from t1 to t2 allows for reliable adhesion.

- t3 (8.2 s): The Bag Pick-and-Transport Unit reaches the top of its stroke (4.2 s travel time from t2), triggering a limit switch (Switch 1). Vacuum Pump 2 is activated, causing Suction Cup Set 2 to adsorb the bag. Vacuum Pump 1 is then deactivated.

- t4 (9.2 s): After a 1-second dwell to ensure bag transfer, the stepper motor reverses direction.

- t5 (9.538 s): The Bag Opening Unit completes its action (0.338 s from t4), fully opening the bag mouth. The end effector is now ready.

- t6 (11.538 s): The robotic arm moves the end effector from a pre-position (e.g., 30 mm below the fruit) to envelop the fruit with the open bag. This arm motion time is set to 2 seconds. Upon reaching the target, photoelectric sensors and the integrated depth camera confirm correct positioning, triggering the next phase.

- t7 (15.4 s): The main drive completes its return stroke. During this stroke, the Sealing Unit is engaged and crimps the staple (~3.862 s from t6). At the end of the stroke, a second limit switch (Switch 2) is triggered, stopping the motor. The sealing assistant disengages, and the system is reset.

The total time \( T_{total} \) for one complete bagging cycle is therefore the sum of all sequential actions:

$$ T_{total} = t_{adhesion} + t_{transport\_up} + t_{dwell} + t_{open} + t_{arm\_move} + t_{seal} $$

$$ T_{total} = 3\,s + 4.2\,s + 1\,s + 0.338\,s + 2\,s + 3.862\,s = 15.4\,s $$

This analysis clearly shows that the cycle time is dominated by the mechanical transport phases (governed by stepper motor speed) and the robotic arm’s movement speed. Sensor processing times are negligible (milliseconds).

| Phase | Action Description | Start Time (s) | End Time (s) | Duration (s) | Governing Component |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initialization & Adhesion | Pump on, electromagnet push, bag pickup | 0.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Vacuum Pump, Electromagnet |

| Bag Transport Up | Lifting bag to opening station | 4.0 | 8.2 | 4.2 | Stepper Motor Speed & Screw Lead |

| Bag Transfer & Dwell | Switch vacuum, ensure grip transfer | 8.2 | 9.2 | 1.0 | Control Logic |

| Bag Opening | Mechanical opening of bag mouth | 9.2 | 9.538 | 0.338 | Stepper Motor Speed & Linkage |

| Robotic Arm Positioning | Move end effector to envelop fruit | 9.538 | 11.538 | 2.0 | Robotic Arm Velocity |

| Sealing & Reset | Crimp staple and return drive to home | 11.538 | 15.4 | 3.862 | Stepper Motor Speed & Sealing Mechanics |

| Total Cycle Time | 0.0 | 15.4 | 15.4 |

Discussion and Potential for Efficiency Enhancement

The developed end effector demonstrates a viable solution for the automated bagging of short-stemmed fruits. The integrated, single-motor design is mechanically elegant and robust. However, the current cycle time of 15.4 seconds per fruit highlights areas for significant improvement to match or surpass human labor rates in practical applications.

The cycle time equation \( T_{total} \) reveals the primary bottlenecks:

$$ T_{total} \propto \frac{1}{v_{trans}} + \frac{1}{v_{arm}} + C $$

where \( v_{trans} \) is the linear velocity of the end effector’s internal drive, \( v_{arm} \) is the velocity of the robotic arm’s final positioning move, and \( C \) represents the fixed dwell and adhesion times.

Strategies for Improvement:

- Increase Stepper Motor Performance: Using a higher-power stepper motor or a servo motor with a closed-loop controller would allow for faster accelerations and higher steady-state speeds without losing steps. If the motor speed \( r \) could be doubled to 900 rpm (15 rev/s), the transport velocity \( v_{trans} \) would become 60 mm/s. This would halve the transport and sealing motion times, potentially saving over 4 seconds per cycle.

- Optimize Robotic Arm Trajectory and Speed: The 2-second arm movement is a major contributor. Employing a faster robotic arm and optimizing its path planning to minimize the distance traveled between sequential fruits could drastically reduce this time. Implementing predictive motion, where the arm begins moving towards the next fruit while the end effector completes its sealing reset, could also yield gains.

- Lightweighting the End Effector: Reducing the mass of the end effector through topology optimization and the use of advanced lightweight materials (e.g., carbon fiber composites, high-strength aluminum alloys) would reduce inertia. This allows for higher acceleration and deceleration rates from both the internal motor and the robotic arm, further shortening non-constant velocity portions of the movement profile.

- Parallelization of Operations: Future iterations could explore designs where bag picking for the next cycle occurs in parallel with the sealing operation of the current cycle, though this would increase mechanical complexity.

In conclusion, the presented bagging robot and its innovative end effector address a specific and challenging niche in agricultural automation. The mathematical modeling of its subsystems provides a clear framework for understanding its performance and guiding its future development. By focusing on enhancing the drive system’s power, the robotic arm’s speed, and the overall mass of the end effector, the cycle time can be significantly reduced, paving the way for commercially viable robotic peach bagging systems.