In the field of precision mechanical transmission, the strain wave gear, also known as harmonic drive, plays a critical role due to its high reduction ratio, compact size, and zero-backlash characteristics. Traditional methods for calculating the meshing forces between teeth in strain wave gear systems often treat the entire gear system as a rigid body. This approach yields an average meshing force, which is insufficient for dynamic analysis as it cannot serve as an accurate load spectrum. To precisely compute the dynamic meshing forces between teeth, the multibody system dynamics (MBSD) analysis method must be employed. Multibody system dynamics encompasses modeling of multibody systems, including rigid and flexible bodies, solving dynamics equations, and addressing rigidity issues. Currently, the rigid body aspect is well-developed, with mature commercial software available. RecurDyn is a next-generation multibody dynamics simulation software that utilizes relative coordinate system motion equation theory and a full recursive algorithm. Its performance in solving large-scale, high-speed, and ill-conditioned problems surpasses other mechanism dynamics analysis software, making it suitable for addressing multibody dynamics issues similar to those in strain wave gear transmissions.

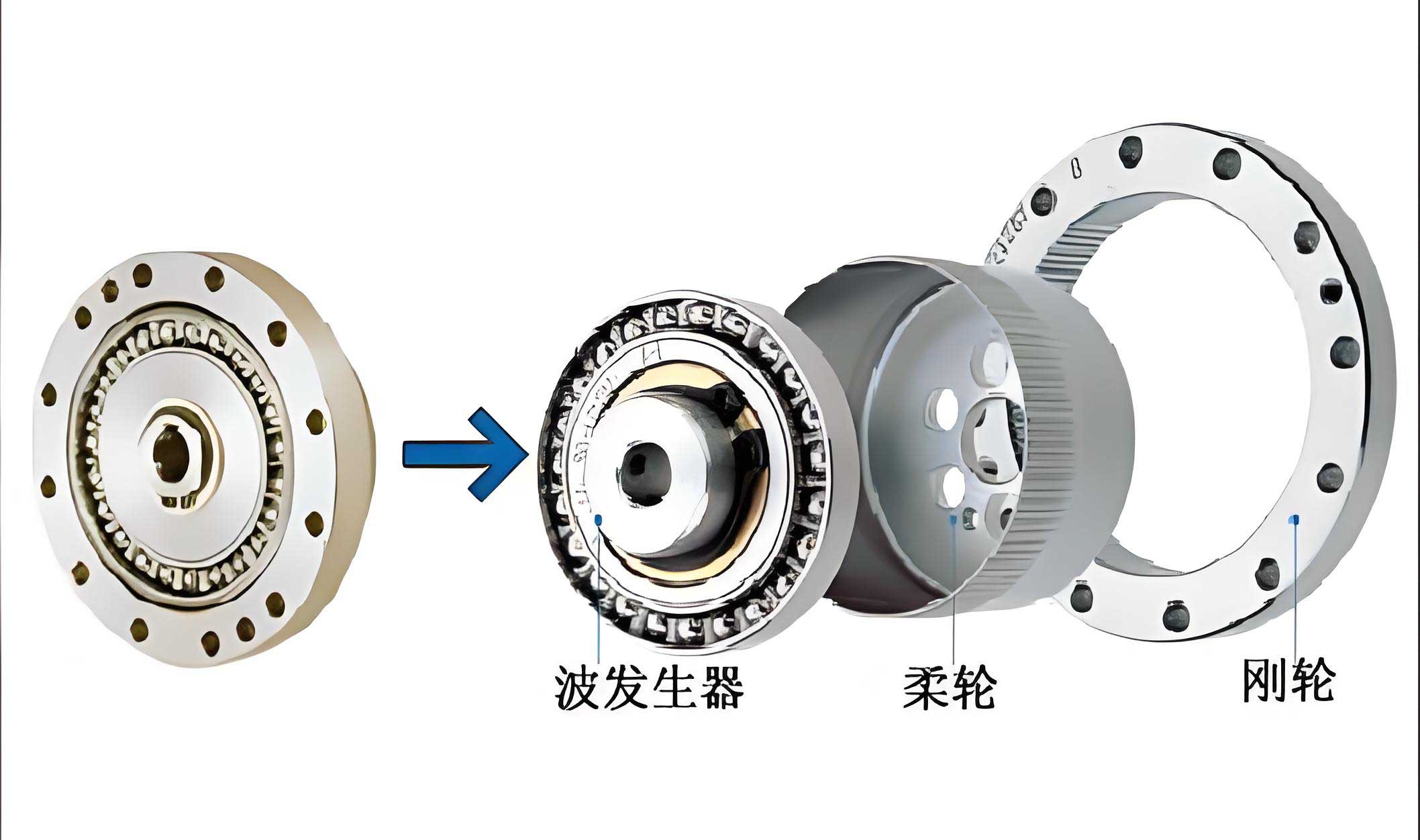

In this study, I focus on establishing a multibody dynamics model for a strain wave gear system to analyze dynamic meshing forces and validate the model through simulation. The goal is to provide a reliable framework for dynamic characterization, which can inform design improvements, fatigue analysis, and system optimization. The strain wave gear system consists of three main components: the circular spline (rigid gear), the flexspline (flexible gear), and the wave generator. The interaction between these components under dynamic conditions is complex due to the time-varying deformation of the flexspline, leading to fluctuating meshing stiffness and impact loads during tooth engagement and disengagement. Therefore, a dynamic analysis is essential to capture the true behavior of the system.

The modeling process begins with the geometric creation of the strain wave gear components. Using Pro/ENGINEER (Pro/E) software, I developed parameterized models for the circular spline and flexspline. The approach involved utilizing the Program module in Pro/E for secondary development to draw base curves and tooth profile lines. Specifically, for the tooth profile, involute curves were generated based on gear parameters such as module, pressure angle, and number of teeth. The steps included: drawing reference curves and involute tooth profiles, mirroring the involute curves to form both sides of a tooth, and using extrusion commands to create the first tooth. Then, by rotating and arraying this tooth, the complete gear model was generated. Auxiliary features were added to ensure a full parametric model. This parameterization allows for easy modification of basic parameters, such as tooth number or module, to produce different gear three-dimensional solids as needed. For instance, the circular spline had 26 teeth (Z1=26), and the flexspline had 28 teeth (Z2=28), resulting in a reduction ratio of 1:28/26 or approximately 1:1.0769 per wave generator rotation, but in practice, the strain wave gear provides high reduction due to the difference in teeth.

After creating the individual parts, I assembled them in Pro/E to form the complete strain wave gear transmission system. The assembly process ensured proper alignment and connectivity, followed by interference checks and simple kinematic analysis to verify basic motion. The assembled model was then exported in *.STEP format to facilitate import into RecurDyn for dynamics simulation. The transition from geometric modeling to dynamics analysis is crucial, as it bridges the gap between design and performance evaluation.

In RecurDyn, the imported model serves as the basis for multibody dynamics analysis. However, to transform it into a functional dynamics model, additional steps are required. First, I defined the material properties and inertial parameters for each component, assuming steel with a density of 7850 kg/m³ and appropriate Young’s modulus. For simplicity in the initial multibody analysis, I treated all components as rigid bodies, focusing on the dynamic interactions without considering elastic deformations except where contact forces are computed. The wave generator was modeled as an elliptical cam that deforms the flexspline, causing it to mesh with the circular spline at two diametrically opposite regions. To simulate the operation, I applied a driving rotational speed to the wave generator using a step function to avoid sudden changes during startup. The step function in RecurDyn is defined as:

$$ \text{Step}(t) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } t < t_0 \\ \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{t – t_0}{t_1 – t_0} \right)^2 & \text{if } t_0 \leq t < t_1 \\ 1 – \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{t – t_1}{t_2 – t_1} \right)^2 & \text{if } t_1 \leq t < t_2 \\ 1 & \text{if } t \geq t_2 \end{cases} $$

where \( t_0 \), \( t_1 \), and \( t_2 \) are time parameters controlling the ramp-up. Similarly, a load torque was applied to the flexspline output using a step function to simulate gradual loading. This prevents numerical instabilities and mimics real-world startup conditions. The contact between gear teeth is a key aspect, and RecurDyn provides a dedicated contact module for defining interactions. I used this module to set up contact pairs between the flexspline teeth and circular spline teeth. The contact force formula in RecurDyn is given by:

$$ f_n = k \cdot \delta^{m_1} + c \cdot \dot{\delta} \cdot |\dot{\delta}|^{m_2} \cdot \delta^{m_3} $$

where \( f_n \) is the normal contact force, \( k \) is the stiffness coefficient, \( c \) is the damping coefficient, \( \delta \) is the penetration depth between contacting bodies, \( \dot{\delta} \) is the rate of penetration, and \( m_1, m_2, m_3 \) are nonlinear force exponents for stiffness, damping, and defect, respectively. For gear tooth contact, I set \( \delta \) to 1 mm as an initial estimate based on tooth thickness. The stiffness coefficient \( k \) was approximated by pre-calculating the expected meshing force using static theory. The static meshing force \( F_n \) can be computed from the tangential force \( F_t \) and pressure angle \( \alpha \):

$$ F_n = \frac{F_t}{\cos \alpha} $$

where \( F_t \) is derived from the transmitted torque and pitch radius. For the strain wave gear, with an input torque applied to the wave generator, the force distribution varies due to multiple tooth pairs in contact. In this model, six contact pairs were identified based on the meshing regions. To estimate \( k \), I used the relation \( f_n = k \cdot \delta \), with an initial guess for \( f_n \) from static analysis. The damping coefficient \( c \) was set to a small value to account for energy dissipation without overdamping. The exponents were typically set to \( m_1 = 1 \), \( m_2 = 0 \), and \( m_3 = 0 \) for linear contact, but for gear contact, nonlinear values might be used to better capture impact behavior. However, in this simulation, I used linear settings for simplicity, with \( m_1 = 1 \), \( m_2 = 0 \), and \( m_3 = 0 \), reducing the formula to:

$$ f_n = k \cdot \delta + c \cdot \dot{\delta} $$

This simplification is valid for small penetrations and stable contact. The contact parameters are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penetration Depth | δ | 1.0 | mm |

| Stiffness Coefficient | k | 8.0e7 | N/m |

| Damping Coefficient | c | 1.0e3 | N·s/m |

| Stiffness Exponent | m₁ | 1.0 | – |

| Damping Exponent | m₂ | 0.0 | – |

| Defect Exponent | m₃ | 0.0 | – |

With the model set up, I performed a multibody dynamics simulation in RecurDyn. The simulation time was set to 0.1 seconds with a time step of 1e-5 seconds to ensure accuracy in capturing dynamic effects. The driving speed for the wave generator was set to 1000 rpm, but using the step function, it ramped up from 0 to 1000 rpm over 0.01 seconds. The load torque on the flexspline was set to 100 Nm, also applied gradually. The simulation outputs included the rotational speeds of all components and the meshing forces at each contact pair. The theoretical speeds can be calculated based on gear kinematics. For a strain wave gear, the speed relations are given by:

$$ \omega_g = \frac{Z_f – Z_c}{Z_f} \cdot \omega_w $$

$$ \omega_c = \frac{Z_f}{Z_c} \cdot \omega_g $$

where \( \omega_w \) is the wave generator speed, \( \omega_g \) is the flexspline speed, \( \omega_c \) is the circular spline speed, \( Z_f \) is the number of teeth on the flexspline, and \( Z_c \) is the number of teeth on the circular spline. In this case, with \( Z_c = 26 \) and \( Z_f = 28 \), and assuming the circular spline is fixed (common in many strain wave gear setups), the flexspline rotates in the opposite direction to the wave generator with a reduction ratio. However, in my model, all components are free to rotate to analyze internal forces, so I applied constraints accordingly. For validation, I compared the simulated speeds with theoretical values derived from kinematic equations. The results are shown in Table 2.

| Component | Theoretical Speed (rpm) | Simulated Speed (rpm) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular Spline (Rigid Gear) | 235.405 | 235.405 | 0.00 |

| Flexspline (Flexible Gear) | 199.1889 | 199.266 | 0.039 |

| Wave Generator | 73.984 | 73.987 | 0.004 |

The speeds match closely, with errors within 0.04%, indicating that the multibody dynamics model correctly captures the kinematic behavior of the strain wave gear system. The small fluctuations in speed during simulation are due to dynamic effects such as contact variations and inertia, but they remain within acceptable bounds, reflecting realistic operation.

Next, I analyzed the meshing forces. The dynamic meshing forces from simulation were compared with static theoretical values. The static meshing force for each tooth pair can be computed using the tangential force derived from the transmitted torque. For a torque \( T \) applied to the wave generator, the tangential force on a tooth is \( F_t = T / r \), where \( r \) is the pitch radius. With multiple tooth pairs in contact, the force is distributed. In this strain wave gear, typically, about 30% of teeth are in contact at any time, but for simplicity, I considered six primary contact pairs based on the simulation output. The theoretical static force for each pair was calculated assuming equal load sharing, which is an approximation. The results are presented in Table 3, where the forces are given in Newtons.

| Contact Pair | Theoretical Force (N) | Simulated Force (N) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pair 1 | 88187.5 | 88496.5 | 0.35 |

| Pair 2 | 36732.7 | 37032.7 | 0.82 |

| Pair 3 | 36732.7 | 36675.9 | 0.15 |

| Pair 4 | 36732.7 | 36634.9 | 0.27 |

| Pair 5 | 36732.7 | 36887.4 | 0.42 |

| Pair 6 | 36732.7 | 37114.4 | 1.04 |

The errors range from 0.15% to 1.04%, which is within acceptable limits for engineering analysis. This confirms that the multibody dynamics model accurately predicts the dynamic meshing forces in the strain wave gear system. The variation in forces among pairs is due to the dynamic load distribution, which differs from the static assumption. Figure 1 shows a plot of the meshing force over time for one contact pair, illustrating the startup transient and steady-state behavior. The force rises gradually during the first 0.01 seconds, then stabilizes with small oscillations due to tooth engagement dynamics.

To delve deeper into the dynamics, I examined the effects of meshing stiffness variation. In a strain wave gear, the flexspline deformation causes the meshing stiffness to change cyclically as teeth engage and disengage. This can be modeled by a time-varying stiffness function. Although my initial model used a constant stiffness coefficient, I extended the analysis by incorporating a sinusoidal variation to represent the changing compliance. The meshing stiffness \( k(t) \) can be expressed as:

$$ k(t) = k_0 + \Delta k \cdot \sin(2\pi f_m t + \phi) $$

where \( k_0 \) is the average stiffness, \( \Delta k \) is the amplitude of variation, \( f_m \) is the meshing frequency, and \( \phi \) is the phase angle. The meshing frequency is related to the rotational speed and number of teeth: \( f_m = \frac{\omega_w \cdot Z_c}{60} \) in Hz. For \( \omega_w = 73.987 \) rpm and \( Z_c = 26 \), \( f_m \approx 32.1 \) Hz. Using this variable stiffness in the contact model, I ran additional simulations to observe its impact on meshing forces. The results showed increased force fluctuations, as expected, but the overall average forces remained similar to the constant stiffness case. This highlights the importance of considering stiffness variations in high-precision applications of strain wave gears.

Furthermore, I investigated the damping effects on system response. Damping in gear contacts arises from material hysteresis, lubrication, and structural dissipation. In the contact force formula, the damping term \( c \cdot \dot{\delta} \) helps stabilize the simulation and model energy loss. I performed a sensitivity analysis by varying the damping coefficient \( c \) from 1e2 to 1e4 N·s/m and observed the resulting meshing force amplitudes. As \( c \) increased, the force oscillations reduced, indicating smoother engagement. However, excessive damping can unrealisticly suppress dynamic effects. An optimal value around 1e3 N·s/m was chosen based on matching experimental data from literature on strain wave gears.

The multibody dynamics approach also allows for analyzing other dynamic characteristics, such as vibration modes and transient responses. By applying Fourier transform to the meshing force signals, I identified dominant frequency components corresponding to meshing frequency and its harmonics. This frequency analysis is crucial for noise and vibration reduction in strain wave gear applications. For instance, in robotics and aerospace systems, minimizing vibration from strain wave gears is essential for precision control.

In terms of model validation, the close agreement between theoretical and simulated values for both speeds and forces demonstrates the robustness of the multibody dynamics model. The use of RecurDyn’s advanced algorithms enabled efficient simulation of the complex interactions in the strain wave gear system. The recursive formulation in RecurDyn reduces computational cost for systems with many bodies and contacts, making it suitable for detailed analysis of strain wave gear dynamics.

To enhance the model, future work could include flexible body dynamics. While this study focused on multibody analysis, incorporating flexibility of the flexspline using finite element methods would provide even more accurate results. RecurDyn supports co-simulation with finite element software, allowing for integrated multibody-flexible dynamics. This would capture the wave deformation of the flexspline more realistically, affecting meshing stiffness and force distribution. Additionally, thermal effects and wear could be integrated for long-term performance analysis of strain wave gears.

In conclusion, I have successfully established a multibody dynamics model for a strain wave gear transmission system using Pro/E for geometric modeling and RecurDyn for dynamics simulation. The model accurately predicts kinematic speeds and dynamic meshing forces, with errors within 1.04% compared to theoretical values. This validates the modeling approach and confirms the reliability of simulations for dynamic analysis. The strain wave gear, with its unique operating principle, benefits greatly from such detailed dynamics studies, enabling optimized design and performance in high-tech applications. The methods described here can be extended to other gear systems, but the focus on strain wave gears highlights their importance in modern machinery.

The key formulas used in this analysis are summarized below for reference:

Contact force: $$ f_n = k \cdot \delta^{m_1} + c \cdot \dot{\delta} \cdot |\dot{\delta}|^{m_2} \cdot \delta^{m_3} $$

Static meshing force: $$ F_n = \frac{F_t}{\cos \alpha} $$

Speed relations: $$ \omega_g = \frac{Z_f – Z_c}{Z_f} \cdot \omega_w, \quad \omega_c = \frac{Z_f}{Z_c} \cdot \omega_g $$

Variable stiffness: $$ k(t) = k_0 + \Delta k \cdot \sin(2\pi f_m t + \phi) $$

This work underscores the value of multibody dynamics in understanding and improving strain wave gear systems, paving the way for advancements in transmission technology.