In recent years, the rapid growth of the new energy industry has led to a significant increase in the number of waste lithium-ion batteries. The scarcity of metals such as cobalt and lithium in these batteries makes their recycling highly valuable. Currently, the recycling process in many regions relies heavily on manual labor, which is inefficient and prone to errors. To address this, automation through robotics has emerged as a promising solution. Specifically, the development of a specialized end effector for handling waste batteries during sorting and disassembly stages can enhance efficiency and reusability. This article presents the design and analysis of a robot end effector tailored for handling waste lithium-ion batteries. The end effector is capable of adapting to various battery sizes and weights, ensuring secure gripping and transportation. We focus on the mechanical design, kinematic and dynamic modeling, optimization of key parameters, and simulation-based validation. The goal is to provide a robust and adaptable tool that can integrate with industrial robots for automated battery recycling lines.

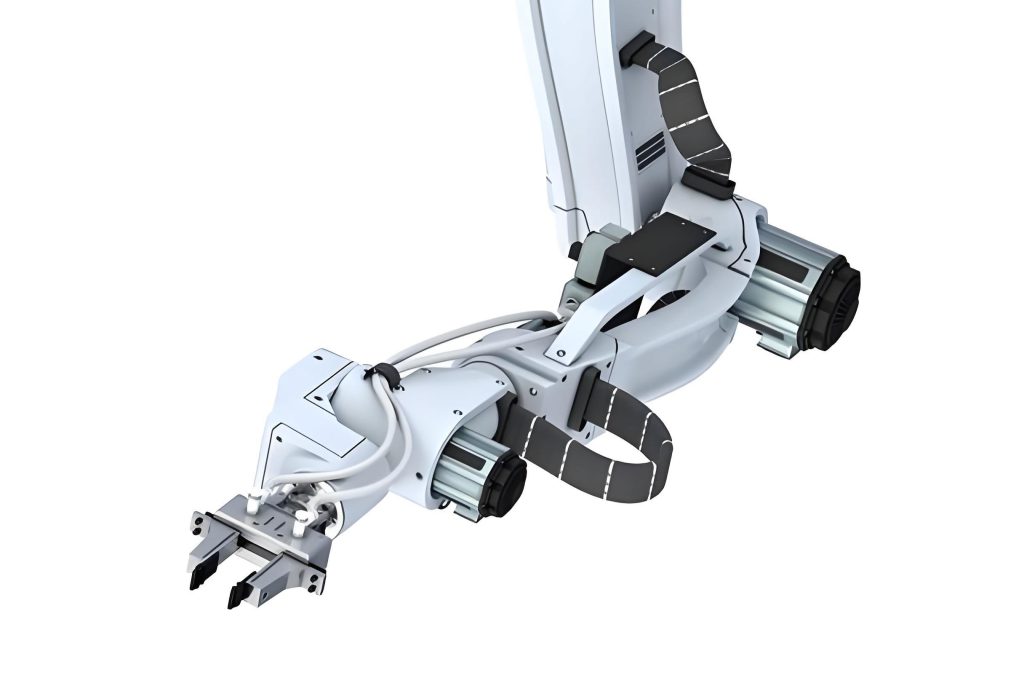

The end effector, often referred to as the robot’s hand, is a critical component installed on the wrist of an industrial robot to grasp workpieces or perform tasks. For waste battery handling, the end effector must accommodate batteries with dimensions ranging from 300 mm × 400 mm × 50 mm to 600 mm × 600 mm × 170 mm (length × width × height) and a maximum weight of 50 kg. The workflow involves visual positioning of battery modules after removal of the casing, followed by the end effector approaching, lifting the module via suction, gripping it with clamping jaws, and transporting it to a conveyor. This process demands precision, adaptability, and reliability from the end effector. Our design incorporates multiple mechanisms: a positioning system, an adsorption system, a transmission system, and a clamping system, all integrated into a compact structure. The transmission system, based on a six-bar linkage, is particularly emphasized due to its advantages in force amplification, low impact, and holding capability, making it ideal for gripping operations. In this article, we delve into the details of each mechanism, with a thorough analysis of the six-bar linkage’s kinematics and dynamics. We also employ optimization algorithms to refine design parameters and validate performance through simulations.

The overall structure of the end effector consists of several key components. The main body includes a connection plate for attaching to the robot, a housing, and fixed shafts for the linkage. The positioning mechanism utilizes two ball screws with opposite thread directions, driven by a motor, to adjust the end effector’s width according to battery size. This allows synchronous movement of both sides to ensure proper alignment. The adsorption system employs a vacuum sponge sucker, which is more effective than conventional suction cups due to its ability to conform to uneven surfaces and maintain vacuum integrity even with minor leaks. The sponge sucker is connected to a vacuum generator and includes check valves to preserve suction force. The transmission system is centered on an elbow six-bar linkage, actuated by a pneumatic cylinder, which converts linear motion into rotational motion for the clamping jaws. The clamping jaws, equipped with rubber pads, provide secure gripping with minimal slippage. Additionally, a vision system mounted on the robot aids in target localization. This integrated design enables the end effector to handle diverse battery shapes and sizes efficiently. In the following sections, we break down each subsystem, starting with the adsorption and positioning mechanisms, before focusing on the six-bar linkage analysis and optimization.

The adsorption mechanism is crucial for initially lifting the battery module. We selected a vacuum sponge sucker model YM130×610AC-A5, which operates at a supply pressure of 0.4–0.8 MPa and provides a theoretical maximum suction force of 696 N. The sponge material ensures good contact with irregular surfaces, and built-in check valves prevent vacuum loss if the sucker does not fully cover the battery. The air consumption is 220 L/min, and the maximum vacuum flow rate is 730 L/min. This mechanism is supported by a cylinder that adjusts the vertical position of the sponge sucker, allowing it to press down and lift the battery. The specifications are summarized in Table 1.

| Model | Supply Pressure (MPa) | Air Consumption (L/min) | Max Vacuum Flow (L/min) | Theoretical Max Suction Force (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YM130×610AC-A5 | 0.4–0.8 | 220 | 730 | 696 |

The positioning mechanism uses ball screws for precise linear adjustment. Ball screws offer high transmission efficiency and low friction compared to trapezoidal screws, reducing required torque by about one-third. They also allow reversible motion, enabling the end effector to return to its initial position after gripping. The screws are coupled with bearing seats and sliders to move the end effector body laterally, adapting to different battery widths. This mechanism is driven by a motor through a coupling, ensuring synchronized movement on both sides. The design prioritizes accuracy and repeatability to complement the vision system’s positioning data.

The transmission system is the core of the end effector, where we implement an elbow six-bar linkage. This type of linkage, a variant of the Stephenson III mechanism, is known for its favorable transmission angles, force amplification, and holding characteristics. It consists of a frame (link 1), a slider (link 2), connecting rods (links 3, 4, 5), and a crank (link 6). The pneumatic cylinder drives the slider linearly over a stroke of 50 mm, which in turn moves the linkage to rotate the clamping jaws. The kinematics of this six-bar linkage can be modeled using complex vector methods. Define the positions and angles as shown in the schematic: let $l_i$ denote the length of link $i$, $\theta_i$ the angle of link $i$ measured from the positive x-axis, $s_2$ the slider displacement, and $h$ the vertical distance. The closed-loop vector equations are:

$$ \begin{cases} l_4 + l_3 = x + y + s_2 \\ l_4 + l_5 + l_6 = h \end{cases} $$

where $x$ and $y$ are fixed position parameters. Expressing in complex form using Euler’s formula $e^{i\phi} = \cos \phi + i \sin \phi$, we derive the following system:

$$ \begin{cases} l_4 \cos \theta_4 + l_3 \cos \theta_3 = x + s_2 \\ l_4 \sin \theta_4 + l_3 \sin \theta_3 = y \\ l_4 \cos \theta_4 + l_5 \cos \theta_5 + l_6 \cos \theta_6 = 0 \\ l_4 \sin \theta_4 + l_5 \sin \theta_5 + l_6 \sin \theta_6 = h \end{cases} $$

Assuming the slider displacement follows a motion profile over a 2-second cycle for gripping: $s_2 = -\frac{S_2}{2} \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{2} t\right) + \frac{S_2}{2}$, with $S_2 = 50$ mm, we solve for the angles. For instance, $\theta_3$ can be found from:

$$ H \sin \theta_3 + K \cos \theta_3 + L = 0 $$

where $H = 2y l_3$, $K = 2x l_3 + 2s_2 l_3$, and $L = l_4^2 – x^2 – 2x s_2 – s_2^2 – y^2 – l_3^2$. Then,

$$ \theta_3 = 2 \arctan\left( \frac{H + \sqrt{H^2 + K^2 – L^2}}{K – L} \right) $$

Similarly, $\theta_4 = \arcsin\left( \frac{y – l_3 \sin \theta_3}{l_4} \right)$. The angles for links 5 and 6 are derived from the second loop:

$$ \theta_5 = 2 \arctan\left( \frac{M + \sqrt{M^2 + N^2 – O^2}}{N – O} \right) $$

$$ \theta_6 = \arccos\left( -\frac{l_4 \cos \theta_4 + l_5 \cos \theta_5}{l_6} \right) $$

with $M = 2l_4 l_5 \sin \theta_4 – 2h l_5$, $N = 2l_4 l_5 \cos \theta_4$, and $O = l_4^2 + l_5^2 + h^2 – 2h l_4 \sin \theta_4 – l_6^2$.

Differentiating with respect to time yields angular velocities and accelerations. For example, the angular velocities are:

$$ \omega_3 = -\frac{v_2 \cos \theta_4}{l_3 \sin(\theta_3 – \theta_4)} $$

$$ \omega_4 = -\frac{l_3 \omega_3 \cos \theta_3}{l_4 \cos \theta_3} $$

$$ \omega_5 = -\frac{l_4 \omega_4 \cos(\theta_4 – \theta_6)}{l_5 \sin(\theta_5 – \theta_6)} $$

$$ \omega_6 = -\frac{l_4 \omega_4 \cos \theta_4 + l_5 \omega_5 \cos \theta_5}{l_6 \cos \theta_6} $$

where $v_2$ is the slider velocity. The angular accelerations are obtained by further differentiation, but for brevity, we omit the full expressions here. These kinematic equations form the basis for dynamic analysis and optimization.

To optimize the six-bar linkage parameters, we apply hybrid algorithms combining global and local search methods. The design variables are $x$, $y$, $h$, $l_4$, $l_5$, and $l_6$, with $l_3$ being dependent. The objective function $P$ is a weighted sum of three terms: angular velocity fluctuation $P_1$, maximum pressure angle at link 6 $P_2$, and error in the crank’s final angle relative to 60° $P_3$. That is:

$$ P = R_1 P_1 + R_2 P_2 + R_3 P_3 $$

where $P_1 = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n [\omega(i) – \bar{\omega}]^2$, $P_2 = \max \alpha_y$, and $P_3 = |\theta_6 / 1.046 – 1|$ (since 60° ≈ 1.046 rad). The weights $R_1$, $R_2$, $R_3$ are set based on importance. Constraints include the Grashof condition for the crank, limits on angular acceleration $\alpha_i \leq \alpha_{\text{max}}$, bounds on link lengths $l_{\text{min}} \leq l_i \leq l_{\text{max}}$, and pressure angle limits.

We use two approaches: Genetic Algorithm-BFGS (GA-BFGS) and Particle Swarm Optimization-BFGS (PSO-BFGS). GA provides global exploration through selection, crossover, and mutation, while PSO simulates bird flocking with particle updates. Both are coupled with the BFGS quasi-Newton method for local refinement and an interior point method to handle constraints. The optimization process yields two sets of parameters, as shown in Table 2.

| Method | $l_3$ | $l_4$ | $l_5$ | $l_6$ | $x$ | $y$ | $h$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA-BFGS | 112.25 | 64.28 | 62.37 | 50.00 | 105.18 | 19.51 | 99.16 |

| PSO-BFGS | 113.01 | 63.63 | 67.99 | 51.89 | 108.94 | 18.61 | 95.61 |

The corresponding objective function values are compared in Table 3. The GA-BFGS result gives a lower overall $P$, but PSO-BFGS yields a higher maximum pressure angle. Based on further analysis of dynamic performance, we select the GA-BFGS parameters for the end effector design, as they provide smoother motion characteristics.

| Method | $P$ | $P_1$ | $P_2$ | $P_3$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA-BFGS | 0.4051 | 0.5876 | 1.1215 | 0.1954 |

| PSO-BFGS | 0.4517 | 0.5941 | 1.1924 | 0.1361 |

With the kinematic model established, we proceed to dynamics analysis to determine the required driving force. Using Lagrange’s equation for a single-degree-of-freedom system with generalized coordinate $q = s_2$ (slider displacement), the equation of motion is:

$$ J_e \ddot{q} + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial J_e}{\partial q} \dot{q}^2 = Q $$

where $J_e$ is the equivalent inertia, and $Q$ is the generalized force (i.e., the cylinder driving force $F_2$). The equivalent inertia is computed from the kinetic energy $T = \frac{1}{2} J_e \dot{q}^2$, with contributions from all links’ masses and moments of inertia. Expressing link centroids in terms of $q$ and differentiating, we derive $J_e$ as:

$$ J_e = \sum_{i=2}^6 \left[ m_i \left( \left( \frac{\partial x_{si}}{\partial q} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{\partial y_{si}}{\partial q} \right)^2 \right) + J_i \left( \frac{\partial \theta_i}{\partial q} \right)^2 \right] $$

where $m_i$ and $J_i$ are mass and mass moment of inertia of link $i$, and $x_{si}$, $y_{si}$ are centroid coordinates. Solving the equation yields the driving force profile over time. For the selected GA-BFGS parameters, the maximum required force under no-load conditions is 432 N. Therefore, we choose a pneumatic cylinder model SDA40×50SB with a bore diameter of 40 mm, stroke of 50 mm, and thrust range of 500–1000 N at 0.15–1.0 MPa pressure, ensuring sufficient force margin. Table 4 summarizes the cylinder specifications.

| Model | Action Type | Pressure Range (MPa) | Speed Range (mm/s) | Thrust Range (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDA40×50SB | Double-acting | 0.15–1.0 | 30–500 | 500–1000 |

To validate the kinematics, we perform a motion simulation using Adams software. The end effector model is imported, and the driving force is applied to the slider. The resulting angular velocity and acceleration of the clamping jaw (link 6) are compared with the theoretical calculations. The simulation shows close agreement, with smooth curves indicating low impact during gripping. Specifically, the angular velocity remains near zero at the gripping instant, minimizing shock between the jaw and battery. This confirms the advantage of the six-bar linkage in providing controlled motion.

Next, we analyze the end effector’s performance during horizontal handling, considering worst-case scenarios with maximum battery size (50 kg) and robot operating at maximum reach (2.2 m) and angular velocity. The robot model is an IRB6620 with a payload of 150 kg. During rotation, centrifugal and inertial forces act on the battery and clamping jaws. The radial force $F_r$ on the external jaw is computed from components due to rotation about the robot’s base (axis 1) and wrist (axis 6). Let $m_1 = 8.275$ kg be the external jaw mass, $m_2 = 50$ kg the battery mass, $r_1 = 2.2$ m the distance from axis 1 to battery center, $r_6 = 0.3$ m the distance from axis 6 to jaw center, $\omega_1 = 1.74$ rad/s and $\alpha_1 = 5.22$ rad/s² for axis 1, $\omega_6 = 3.31$ rad/s and $\alpha_6 = 23.17$ rad/s² for axis 6. The moments of inertia are $I_{\text{bat-1}} = 70.511$ kg·m², $I_{\text{bat-6}} = 2.429$ kg·m², $I_{\text{jaw-1}} = 15.431$ kg·m², $I_{\text{jaw-6}} = 0.683$ kg·m². The forces are:

$$ F_1 = m_1 (r_1 + r_6) \omega_1^2 = 62.6335 \, \text{N} $$

$$ F_5 = m_2 r_1 \omega_1^2 = 333.036 \, \text{N} $$

$$ F_3 = m_1 r_6 \omega_6^2 = 27.1985 \, \text{N} $$

$$ F_4 = \frac{I_{\text{bat-6}} \alpha_6}{2 r_6} = 93.7998 \, \text{N} $$

$$ F_r = F_1 + F_5 + F_3 + F_4 = 516.6678 \, \text{N} $$

Considering friction between the jaw and battery with coefficient $\mu$, the total gripping force needed is $F = \sqrt{F_r^2 + (\mu F_r)^2}$. For $\mu = 0.5$, $F \approx 661.6447$ N. This force must be supplied by the six-bar linkage output.

We conduct a dynamic simulation in Adams to verify this. The robot motion is programmed with step functions for each axis over a 10-second cycle: axis 1 rotates 100° from 7–10 s to simulate high-speed handling, axis 2 and 3 adjust for reach, and axes 4, 5, 6 are set accordingly. A vertical force of 700 N represents the suction, and a driving force of 500 N is applied to the cylinder from 3–4 s for gripping. Contact constraints with friction are added between battery, ground, jaws, and suction pad. The simulation tracks battery trajectory, velocity, acceleration, and jaw forces. Results show that during gripping (3–4 s), the external jaw experiences an average impact force of 385 N, with peaks up to 380 N, indicating that the 500 N input yields sufficient output. During horizontal rotation (7–10 s), the average force on the external jaw is 625 N, with a maximum of 772 N, close to the calculated 661.6 N. The internal jaw bears lesser loads. The battery’s velocity peaks at 5380 mm/s, and acceleration shows spikes corresponding to suction engagement and centrifugal effects. These results validate that the end effector can handle the specified loads under extreme conditions.

In summary, this end effector design effectively addresses the challenges of waste lithium-ion battery handling. The use of a six-bar linkage provides mechanical advantages such as force amplification and smooth motion, reducing impact during gripping. Optimization with GA-BFGS and PSO-BFGS algorithms refined the linkage parameters to minimize angular velocity fluctuations and pressure angles. Dynamic analysis confirmed that a pneumatic cylinder with 500 N thrust is adequate for no-load operation, and simulations demonstrated that the end effector can withstand radial forces up to 772 N during high-speed robot movements. The integration of a vacuum sponge sucker ensures reliable adsorption on uneven surfaces, while ball screw-based positioning allows adaptation to various battery sizes. Future work could explore lightweight materials for the end effector structure to enhance robot payload efficiency, or incorporate sensors for real-time force feedback. Overall, this end effector offers a robust solution for automating battery recycling processes, contributing to sustainable energy practices. The design principles and analysis methods presented here can also inspire developments in other robotic handling applications where adaptability and precision are key.

The end effector’s performance hinges on the synergistic operation of its components. For instance, the vacuum system must quickly establish suction to lift the battery before the jaws close, and the positioning mechanism must accurately align the end effector based on visual data. The six-bar linkage, as the transmission heart, ensures that the clamping force is maintained even if power is lost, thanks to its self-locking tendency at certain configurations. This is crucial for safety in industrial environments. Moreover, the optimization process highlighted the trade-offs between different performance metrics; for example, a lower pressure angle improves force transmission but may require longer links, affecting compactness. Our chosen compromise via GA-BFGS balances these factors. The simulation results further reinforce the design’s viability, showing that even under dynamic loads, the end effector remains stable and secure. This end effector not only facilitates battery recycling but also serves as a case study in applying advanced optimization techniques to mechanical design. As robotics continues to evolve, such integrated approaches will be essential for creating efficient and reliable end effectors for diverse tasks.