In my work on precision motion control systems, the strain wave gear, often called a harmonic drive, is a critical component I frequently rely on. Its unique operating principle grants it exceptional qualities like high reduction ratios, compactness, and zero-backlash potential. However, achieving and verifying its famed high positional accuracy is a complex challenge. The transmission error, defined as the deviation between the theoretical and actual output position for a given input, is the ultimate metric of this precision. Understanding and quantifying this error is paramount not just for selecting the right component, but for the entire design, manufacturing, and assembly process of servo systems. This analysis delves into the core mechanics of the strain wave gear, dissects the primary sources of its transmission error, and presents a methodology for its comprehensive measurement.

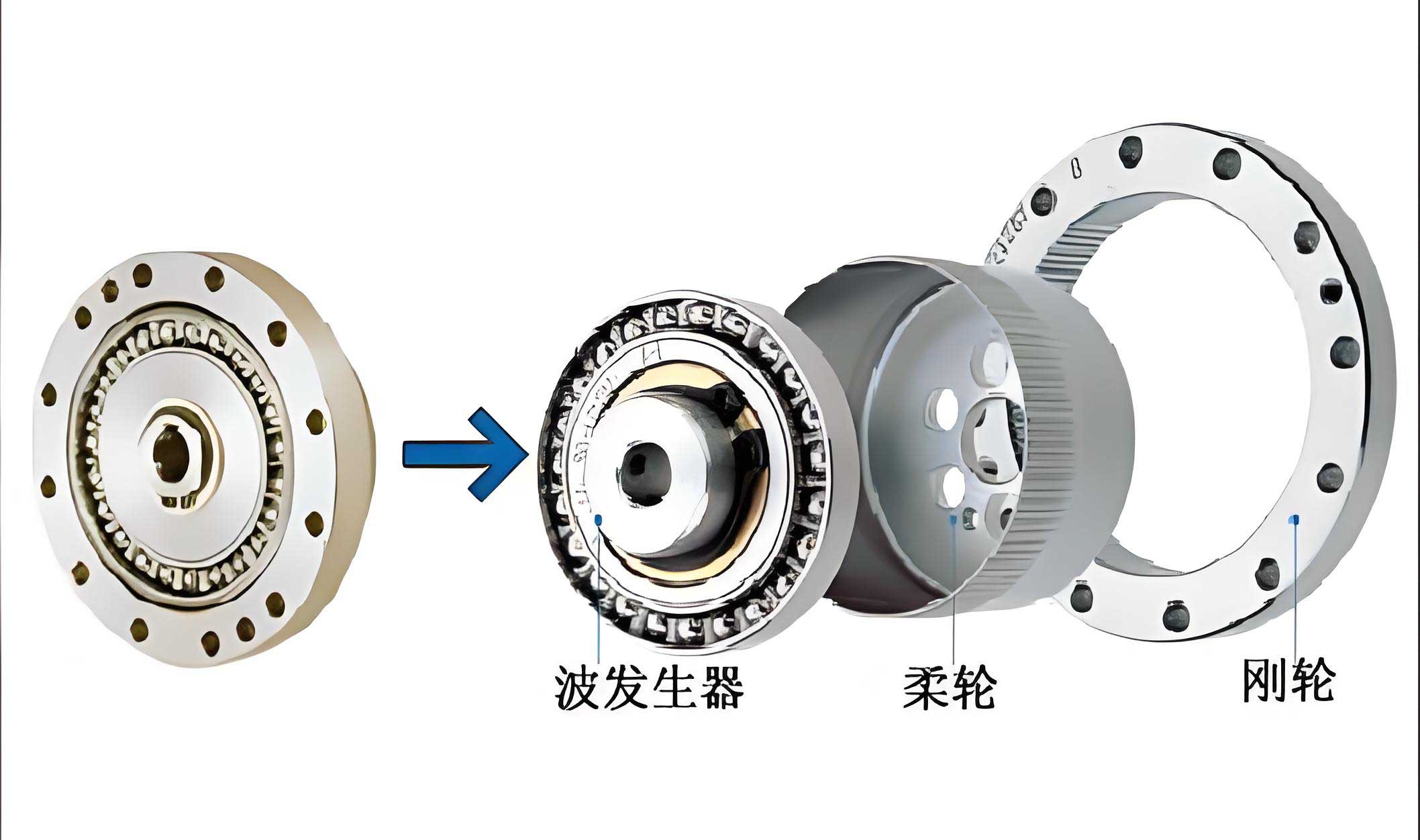

The fundamental operation of a strain wave gear hinges on controlled elastic deformation. It comprises three key elements: a rigid Circular Spline, a flexible Flexspline, and an elliptical Wave Generator that fits inside the Flexspline. The theory of thin-shell elastic deformation provides the mathematical foundation. When the Wave Generator rotates, it induces a controlled elliptical deflection in the Flexspline. This deflection is not static; it propagates as a wave around the Flexspline’s circumference. The radial displacement (W) of the Flexspline’s teeth is intrinsically coupled with a tangential displacement (u). It is this kinematic relationship that facilitates the speed reduction and torque multiplication.

The meshing state between the Flexspline and Circular Spline teeth varies continuously around the circumference. At the major axis of the ellipse, the teeth are in full engagement. Along the minor axis, they are disengaged. This moving wave of engagement is what drives the motion. If we denote ω_H as the angular velocity of the Wave Generator, ω_F as that of the Flexspline, and ω_C as that of the Circular Spline (typically zero in a standard reducer), the gear ratio is derived from kinematic principles. Applying a relative motion of (-ω_H) to the entire system, we can analyze the fixed Wave Generator scenario. The transmission ratio i is then given by the number of teeth on the Flexspline (z_F) and Circular Spline (z_C):

$$ i = \frac{\omega_F – \omega_H}{\omega_C – \omega_H} = -\frac{z_C}{z_F} $$

This equation shows the high-ratio capability, as the difference in tooth count (z_C – z_F) is usually small (e.g., 2), but it appears in the denominator of the ratio expression relative to the Flexspline motion.

The exceptional performance of the strain wave gear is counterbalanced by a complex error landscape. The transmission error (TE) is not a single, simple deviation but a composite of several interrelated errors arising from manufacturing imperfections, assembly, and the inherent elasticity of the components. We can categorize the primary error sources into three main domains, each contributing uniquely to the overall kinematic inaccuracy.

Firstly, we have Backlash or Lost Motion. This is the classic “dead zone” experienced when reversing the direction of rotation. In a perfect strain wave gear with pure rolling contact, backlash could be zero. In reality, it stems from multiple factors: microscopic clearances between mating teeth (tooth flank clearance), minute gaps within the Wave Generator assembly (e.g., between the bearing and the cam), and, significantly, the elastic wind-up of the Flexspline under torsional load. When torque direction reverses, the stored elastic energy releases, causing a momentary unmeshing before contact is re-established on the opposite flank. The total angular backlash φ_b can be modeled as a sum of these contributions:

$$ \varphi_{b} = \Delta_s + \Delta_g + \Delta_f $$

where Δ_s is the torsional wind-up contribution, Δ_g is the geometric clearance from manufacturing, and Δ_f is the deflection-related free motion. This is often converted to an arc-minute value at the output.

Secondly, there is the Stiffness-Dependent Error. The Flexspline is, by design, a compliant element. Its torsional stiffness is finite and non-linear, typically exhibiting a hysteresis curve. For a given applied output torque T_out, the Flexspline and other elements twist elastically, causing a positional lag Δ_θ. This error is directly proportional to the torque and inversely proportional to the system’s composite torsional stiffness K_t. This relationship is often simplified to a linear approximation for servo analysis:

$$ \Delta_e = \frac{T_{out}}{K_t} $$

This means the apparent output position of the strain wave gear changes with load, even if the input is held perfectly constant. This is crucial for systems where payload varies.

Finally, there is the fundamental Kinematic or Motion Error. This is the error present even under no-load, unidirectional rotation. It is caused by imperfections in the conjugate motion itself: deviations in the Wave Generator’s elliptical profile, pitch errors and tooth profile errors on the Flexspline and Circular Spline, and radial run-out of components. A key advantage of the strain wave gear is error averaging. Because multiple teeth (often 10-30% of the total) are in simultaneous contact, individual tooth errors are averaged out. The RMS kinematic error Δ_φ_k is significantly less than that of an equivalent traditional gear pair. It can be approximated by:

$$ \Delta_{\phi k} \approx \Delta_{g} \cdot \frac{k_B}{\sqrt{z_m}} $$

where Δ_g is the error of a single tooth pair, k_B is an empirical factor, and z_m is the number of teeth simultaneously in mesh.

Therefore, the total instantaneous transmission error Δ_TE of a strain wave gear in a bi-directional servo application is a complex amalgamation of these effects. It can be summarized by a comprehensive expression that combines the kinematic error, the manifestation of backlash during reversals (which is a function of the kinematic error and clearance), and the stiffness-dependent deflection:

$$ \Delta_{TE} = \pm \left[ \frac{k_B}{\sqrt{z_m}} \cdot F(\Delta_{profile}, \Delta_{pitch}) + \Phi(\Delta_s, \Delta_g, \Delta_f) \right] + \frac{T_{out}}{K_t} + \epsilon(t) $$

Here, F(·) represents the combined effect of profile and pitch errors, Φ(·) represents the backlash function which engages upon direction change, and ε(t) represents higher-frequency noise or periodic errors. The ± sign indicates the error band. The following table summarizes these primary error sources and their characteristics.

| Error Source | Symbol | Primary Cause | Dependency | Nature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinematic Error | Δ_φ_k | Tooth profile/pitch error, Wave Generator imperfection | Geometry, manufacturing quality | Periodic, direction-insensitive |

| Backlash (Lost Motion) | φ_b | Tooth clearance, assembly gaps, elastic wind-up | Direction reversal, torque history | Discontinuous, appears on reversal |

| Stiffness Error | Δ_e | Elastic torsion of Flexspline and components | Output Torque (T_out), stiffness (K_t) | Proportional to load, reversible |

To validate this theoretical framework and provide quantitative data for system integration, I designed and implemented a high-precision transmission error test system. The core objective was to measure both static (point-to-point) and dynamic (continuous rotation) transmission error under various load conditions.

The system architecture is as follows: A servo motor, driven by a precise motion controller, provides the input rotation. A high-resolution optical encoder (Encoder 1) is directly coupled to the motor shaft to measure the true input angle θ_in, closing the servo loop. The unit under test (the strain wave gear reducer) is mounted on a rigid fixture. Its output shaft is connected to a rotary torque sensor, which in turn couples to a programmable magnetic powder brake acting as the dynamometer for applying controlled load torque T_load. A second, ultra-high-resolution optical encoder (Encoder 2) is directly mounted on the output flange of the reducer to measure the absolute output angle θ_out. All sensor data (θ_in, θ_out, T_load) is synchronously acquired by a data acquisition system at high sampling rates (>10 kHz) and processed on a host computer. The core measurement is the transmission error TE, calculated in real-time:

$$ TE(\theta_{in}) = \theta_{out} – \left( \frac{\theta_{in}}{i} \right) $$

where i is the nominal reduction ratio. This system effectively minimizes parasitic errors from couplings and aligns with metrology best practices.

Static Error Testing: For static testing, the input is commanded to move to 24 equally spaced angular positions over one full output revolution (i.e., many input revolutions). At each position, the system settles, and the average input and output angles are recorded over a short period. This yields a discrete mapping of TE across one cycle. I conducted tests on a commercial precision strain wave gear unit under two conditions: no-load and under a 60 N·m output load. The table below summarizes the key statistical results from the static tests.

| Test Condition | Direction | Mean TE (arc-min) | Peak-to-Peak TE (arc-min) | Standard Deviation (arc-min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-Load | Forward | -1.6 | 5.2 | 1.8 |

| No-Load | Reverse | -1.9 | 5.8 | 2.0 |

| 60 N·m Load | Forward | +3.3 | 6.5 | 2.2 |

| 60 N·m Load | Reverse | +3.1 | 6.1 | 2.1 |

The results clearly show several key aspects of strain wave gear performance. First, the no-load kinematic error is very low, with a mean near zero and a peak-to-peak value around 5.5 arc-min, confirming the excellent inherent accuracy and error-averaging effect. Second, the shift in mean TE from approximately -1.8 arc-min (no-load) to +3.2 arc-min (under 60 N·m load) is a direct manifestation of the stiffness-dependent error Δ_e. The total shift of about 5 arc-min corresponds to the elastic wind-up under that specific load. The consistency between forward and reverse directions under load suggests symmetric stiffness behavior in this unit.

Dynamic Error Testing: To capture the behavior during continuous motion, I performed dynamic tests with the input rotating at a constant 100 RPM (output at a corresponding slow speed) and sampled data at 1 kHz. This reveals the TE as a continuous function of time (or input angle), exposing higher-frequency components and the smoothness of the error curve. The no-load dynamic TE trace showed a repeating, primarily sinusoidal pattern with some higher harmonics superimposed, characteristic of kinematic errors dominated by once-per-revolution and tooth-meshing frequencies. The peak-to-peak amplitude was consistent with the static test, averaging around 5.5 arc-min. Under the 60 N·m load, the entire error waveform was offset by the same ~5 arc-min, but the shape and peak-to-peak amplitude remained largely unchanged, indicating that the load primarily causes a quasi-static torsional deflection rather than altering the kinematic error pattern significantly.

A critical part of dynamic analysis is examining the spectral content of the transmission error. By performing a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) on the time-domain TE signal, we can identify the fundamental frequencies contributing to the error. The most prominent peaks typically occur at:

1. The output revolution frequency (1/rev of output shaft).

2. The tooth meshing frequency (z_F / rev of output shaft).

3. Harmonics of the meshing frequency.

The magnitude of these spectral components provides insight into the root cause of imperfections—for instance, a dominant 1/rev peak points to eccentricity or Wave Generator profile error, while a strong meshing frequency peak indicates tooth profile or pitch error.

The test system demonstrated a measurement capability with an angular precision better than ±6 arc-min, fully encompassing the observed errors of the tested strain wave gear unit. The integrated design, with direct encoder mounting and a high-stiffness loading mechanism, successfully eliminated artifacts from coupling backlash and misalignment that often plague such measurements.

In conclusion, the transmission error of a precision strain wave gear is a multifaceted parameter stemming from kinematic imperfections, elastic deflections, and clearances. My analysis shows that it can be systematically broken down into motion error, backlash, and stiffness error components. The derived relationships and the composite error formula provide a solid theoretical basis for predicting servo system performance. Furthermore, the implemented test system validates this theory, offering a reliable method for the comprehensive evaluation of both static and dynamic transmission accuracy. For engineers integrating these remarkable reducers into high-performance systems, understanding and being able to measure these distinct error contributions is essential for optimizing control algorithms, ensuring positioning accuracy, and ultimately guaranteeing the reliability of applications ranging from aerospace actuators to robotic joints. The strain wave gear, with its unique blend of strengths and nuanced error characteristics, remains a fascinating and indispensable component in the world of precision motion.