In the field of electromechanical actuation systems, the planetary roller screw mechanism stands out as a pivotal component due to its high thrust capacity, speed, precision, longevity, and compact design. As a device that converts rotary motion into linear motion and vice versa, the planetary roller screw has found extensive applications in aerospace control systems, medical equipment, precision machine tools, and other demanding sectors. Among the variants, the inverted planetary roller screw offers unique advantages, such as integration with motors by using the nut as a rotor, leading to a more compact and lightweight assembly with faster response times. However, a critical issue in both standard and inverted planetary roller screw designs is the pitch circle mismatch between the roller thread and the roller gear, often caused by manufacturing tolerances and contact deformation under load. This mismatch induces relative sliding and axial displacement between the roller and the screw, which can increase friction, reduce transmission accuracy and efficiency, and potentially damage the mechanism. Therefore, in this study, I focus on the kinematic analysis of the inverted planetary roller screw, considering the effects of pitch circle mismatch, to develop models for sliding angles, axial displacements, and slip velocities, and to explore how these factors influence the overall performance of the planetary roller screw system.

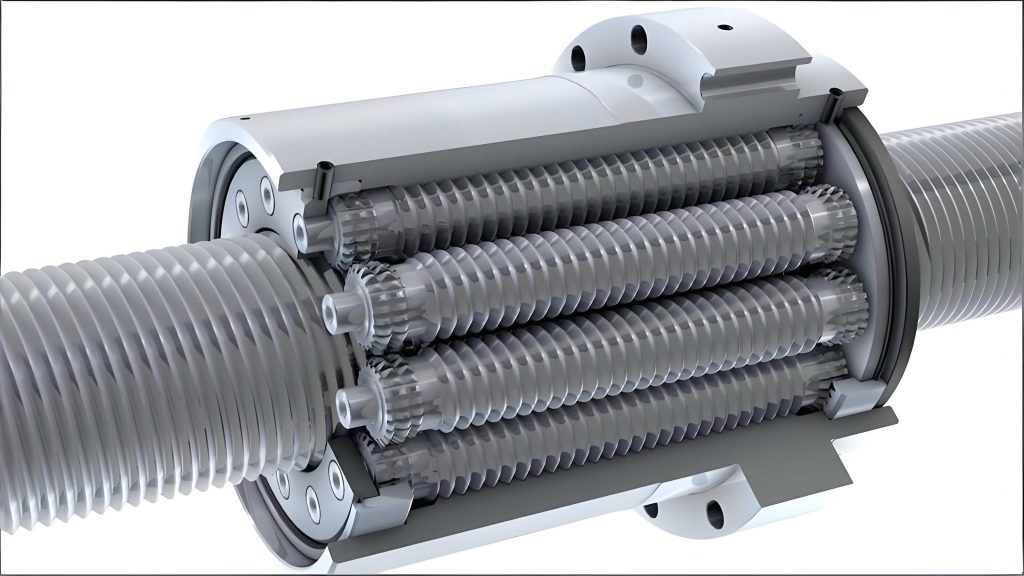

The inverted planetary roller screw consists of several key components: a screw, a nut, multiple rollers, and a carrier. The screw and nut typically feature multi-start threads, while the rollers have single-start threads. The helix angles of the roller and screw threads are identical to ensure no relative axial displacement during pure rolling engagement. Additionally, the rollers and screw have straight gears at their ends to prevent tilting moments from the nut’s helix angle and to constrain relative sliding. The carrier ensures uniform circumferential distribution of the rollers. In operation, the nut acts as the driving element, rotating and engaging with the roller threads to produce planetary motion of the rollers. This motion is then transmitted through the roller-screw thread engagement to generate linear motion of the screw. The planetary roller screw mechanism relies on precise geometric relationships for efficient motion transfer, but deviations due to pitch circle mismatch can disrupt this ideal behavior.

The pitch circle mismatch arises primarily from contact deformation under load. In an inverted planetary roller screw, the roller is subjected to radial forces from both the screw and nut interfaces, compressing the roller thread and causing its pitch circle radius to differ from that of the roller gear. Specifically, the roller thread pitch circle radius (\(R_r\)) becomes smaller than the roller gear pitch circle radius (\(G_r\)) due to deformation, leading to a radial offset. This offset means that during motion, the arc length traversed by the roller gear differs from that by the roller thread, resulting in relative sliding between the roller and screw. The mismatch is quantified by the normalized error \(\epsilon\) and the pitch circle mismatch amount \(\Delta\), defined as:

$$ \epsilon = \frac{R_s – G_s}{R_r} = \frac{G_r – R_r}{R_r} = \frac{\Delta}{R_r} $$

where \(R_s\) and \(G_s\) are the screw thread and gear pitch circle radii, respectively. The geometric relationships for the inverted planetary roller screw must satisfy certain conditions to ensure proper function. For instance, the nut, roller, and screw have the same pitch, and their thread parameters relate as:

$$ R_n = R_s + 2R_r $$

Here, \(R_n\) is the nut thread pitch circle radius. The screw and nut have equal thread starts (\(n_s = n_n = k\)), where \(k\) is the ratio of screw to roller thread pitch circle radii. The gear ratios also match, with \(Z_s / Z_r = R_s / R_r = k\), where \(Z_s\) and \(Z_r\) are the tooth numbers of the screw and roller gears, respectively. These relationships form the basis for kinematic modeling of the planetary roller screw system.

To analyze the kinematics considering pitch circle mismatch, I develop a model that accounts for the relative motion between components. When the nut rotates by an angle \(\theta_n\) with angular velocity \(\omega_n\), the roller undergoes planetary motion, involving both revolution (angle \(\theta_R\)) and rotation (angle \(\theta_r\)). From the gear engagements, the relationship between these angles is derived. At the screw-roller interface, the roller rotation relative to the screw axis is given by:

$$ \theta_r = \frac{G_s + G_r}{G_r} \theta_R $$

Assuming no slip at the nut-roller interface initially, the kinematic condition yields:

$$ (\theta_n – \theta_R) R_n = (\theta_r – \theta_R) R_r $$

Substituting and simplifying, the revolution angle \(\theta_R\) in terms of \(\theta_n\) is:

$$ \theta_R = \frac{G_r R_n}{G_s R_r + G_r R_n} \theta_n $$

Using the geometric relations, this can be expressed as:

$$ \theta_R = \frac{R_n}{2(R_n – R_r)} \theta_n $$

This forms the foundation for calculating sliding effects due to pitch circle mismatch in the planetary roller screw.

The sliding angle, which represents the pure sliding component between the roller and screw, is crucial for understanding friction and wear. When pitch circle mismatch exists, the roller thread and roller gear rotate by different amounts for the same roller axis rotation. The pure rolling angle for the roller thread relative to the screw is:

$$ \theta_R^H = \frac{R_r}{R_s + R_r} \theta_r $$

Similarly, the pure rolling angle for the roller gear is:

$$ \theta_R^G = \frac{G_r}{G_s + G_r} \theta_r $$

The difference gives the sliding angle \(\theta_{slip}\):

$$ \theta_{slip} = \theta_R^G – \theta_R^H $$

Substituting the expressions, I obtain:

$$ \theta_{slip} = \left(1 – \frac{R_r}{G_r}\right) \theta_R $$

This shows that if no mismatch exists (\(R_r = G_r\)), then \(\theta_{slip} = 0\), indicating no relative sliding. However, in practice, mismatch is inevitable due to deformation. Further, by expressing \(\theta_R\) in terms of \(\theta_n\), the sliding angle becomes:

$$ \theta_{slip} = \left(1 – \frac{R_r}{G_r}\right) \frac{G_r R_n}{G_s R_r + G_r R_n} \theta_n $$

This formula highlights how the sliding angle depends on the mismatch and nut rotation in the planetary roller screw system.

Due to the helix angle of the threads, the relative sliding induces axial displacement of the roller relative to the screw. This displacement consists of two parts: one from the pure sliding of the roller thread in the screw thread (\(\delta_1\)), and another from the pure spinning slide of the roller thread (\(\delta_2\)). For a sliding angle \(\theta_{slip}\), these are calculated as:

$$ \delta_1 = \frac{\theta_{slip}}{2\pi} L_s, \quad \delta_2 = -\frac{\theta_{slip}}{2\pi} L_r $$

where \(L_s\) and \(L_r\) are the leads of the screw and roller, respectively. The total axial displacement \(\delta_{rs}\) is:

$$ \delta_{rs} = \delta_1 + \delta_2 = (L_s – L_r) \frac{\theta_{slip}}{2\pi} $$

The leads are related to pitch circle radii and helix angles. For the screw, roller, and nut:

$$ L_s = 2\pi R_s \tan \alpha_s, \quad L_r = 2\pi R_r \tan \alpha_r, \quad L_n = 2\pi R_n \tan \alpha_n $$

and the helix angles satisfy:

$$ \tan \alpha_s = \frac{n_s p}{2\pi R_s}, \quad \tan \alpha_r = \frac{p}{2\pi R_r}, \quad \tan \alpha_n = \frac{n_n p}{2\pi R_n} $$

with \(p\) as the pitch. Since \(n_s = n_n = k\) and the helix angles are equal for screw and roller (\(\alpha_s = \alpha_r\)), substituting leads to:

$$ \delta_{rs} = \left(1 – \frac{R_r}{R_s}\right) \frac{\theta_{slip}}{2\pi} L_n $$

Combining with the expression for \(\theta_{slip}\), the axial displacement becomes:

$$ \delta_{rs} = \left(1 – \frac{R_r}{R_s}\right) \left(1 – \frac{R_r}{G_r}\right) \frac{G_r R_n}{G_s R_r + G_r R_n} \frac{\theta_n}{2\pi} L_n $$

This indicates that if no pitch circle mismatch occurs (\(\Delta = 0\)), then \(\delta_{rs} = 0\). However, in real planetary roller screw applications, such displacement is inevitable and must be accounted for in design, for example, by ensuring adequate tooth width on the screw gear to maintain power transmission over the entire axial travel. Over the total screw travel \(\lambda\), the cumulative axial displacement is:

$$ \delta_{rs}^T = \left(1 – \frac{R_r G_s}{R_s G_r}\right) \frac{G_r R_n}{G_s R_r + G_r R_n} \lambda $$

To assess the impact on system performance, I analyze whether this axial displacement affects the overall lead of the inverted planetary roller screw. The relative axial displacements between components are interrelated. The roller’s axial displacement relative to the nut, \(\delta_{rn}\), includes contributions from roller rotation and revolution. Following similar derivations, I find:

$$ \delta_{rn} = \left( \frac{G_r R_n}{G_s R_r + G_r R_n} – 1 \right) \left(1 + \frac{R_n}{R_s}\right) \frac{\theta_n}{2\pi} L_n $$

The screw’s axial displacement relative to the nut, \(\delta_{sn}\), is the difference between \(\delta_{rn}\) and \(\delta_{rs}\):

$$ \delta_{sn} = \delta_{rn} – \delta_{rs} $$

Substituting the expressions and simplifying, I arrive at a key result:

$$ \delta_{sn} = -\frac{\theta_n}{2\pi} L_n $$

This implies that for one full nut rotation (\(\theta_n = 2\pi\)), the screw moves axially by \(\delta_{sn} = -L_n\) relative to the nut, meaning the magnitude equals the nut lead. Therefore, the pitch circle mismatch causes axial displacement of the roller relative to the screw, but it does not alter the overall transmission lead of the planetary roller screw system. This is crucial for design, as the functional output remains predictable despite internal sliding.

Next, I derive the slip velocities associated with the sliding motion. The total sliding arc length \(\gamma\) at the screw-roller interface comprises contributions from both sliding components:

$$ \gamma = R_r \theta_{slip} + R_s \theta_{slip} = (R_r + R_s) \theta_{slip} $$

The circumferential slip velocity \(v_{cp}\) is obtained by differentiating with respect to time:

$$ v_{cp} = \frac{d\gamma}{dt} = (R_r + R_s) \frac{d\theta_{slip}}{dt} $$

Since \(\frac{d\theta_{slip}}{dt} = \left(1 – \frac{R_r}{G_r}\right) \frac{G_r R_n}{G_s R_r + G_r R_n} \omega_n\), where \(\omega_n = \frac{d\theta_n}{dt}\), the circumferential slip velocity becomes:

$$ v_{cp} = \left(1 – \frac{R_r}{G_r}\right) \frac{G_r R_n (R_r + R_s)}{G_s R_r + G_r R_n} \omega_n $$

Similarly, the axial slip velocity of the roller relative to the screw, \(v_{rs}\), is derived from \(\delta_{rs}\):

$$ v_{rs} = \frac{d\delta_{rs}}{dt} = \left(1 – \frac{R_r}{R_s}\right) \left(1 – \frac{R_r}{G_r}\right) \frac{G_r R_n}{G_s R_r + G_r R_n} \frac{\omega_n}{2\pi} L_n $$

For the roller relative to the nut, the axial slip velocity \(v_{rn}\) is:

$$ v_{rn} = \frac{d\delta_{rn}}{dt} = \left( \frac{G_r R_n}{G_s R_r + G_r R_n} – 1 \right) \left(1 + \frac{R_n}{R_s}\right) \frac{\omega_n}{2\pi} L_n $$

These velocities are essential for evaluating friction losses and thermal effects in the planetary roller screw mechanism.

To generalize the analysis, I non-dimensionalize the formulas using the normalized error \(\epsilon\) and the radius ratio \(k = R_s / R_r\). Recall that \(\epsilon = \Delta / R_r = (G_r – R_r)/R_r\). From the geometric relations, \(G_s = R_s – \Delta = R_s – \epsilon R_r\), and \(G_r = R_r + \Delta = R_r(1 + \epsilon)\). Also, \(R_n = R_s + 2R_r = R_r(k + 2)\). Substituting these into the key equations, I obtain non-dimensional forms that simplify parametric studies. The sliding angle becomes:

$$ \theta_{slip} = \epsilon \frac{k+2}{(\epsilon+2)(k+1)} \theta_n $$

The axial displacement relative to screw lead is:

$$ \frac{\delta_{rs}}{L_n} = \epsilon \frac{(k-1)(k+2)}{k(\epsilon+2)(k+1)} \frac{\theta_n}{2\pi} $$

The total axial displacement over travel \(\lambda\) is:

$$ \delta_{Total} = \frac{\delta_{rs}^T}{\lambda} = \epsilon \frac{(k-1)(k+2)}{k(\epsilon+2)(k+1)} $$

The axial displacement relative to nut lead is:

$$ \frac{\delta_{rn}}{L_n} = \frac{\epsilon – k}{(k+1)(\epsilon+2)} \frac{\theta_n}{2\pi} $$

The non-dimensional circumferential slip velocity is:

$$ \bar{v}_{cp} = \frac{v_{cp}}{\omega_n R_r} = \epsilon \frac{k+2}{\epsilon+2} $$

The non-dimensional axial slip velocities are:

$$ \bar{v}_{rs} = \frac{v_{rs}}{\omega_n L_n} = \epsilon \frac{(k-1)(k+2)}{2\pi k(k+1)(\epsilon+2)} $$

$$ \bar{v}_{rn} = \frac{v_{rn}}{\omega_n L_n} = \frac{\epsilon – k}{2\pi (k+1)(\epsilon+2)} $$

These non-dimensional expressions reveal the influence of \(\epsilon\) and \(k\) on the kinematic behavior of the planetary roller screw. For instance, when \(\epsilon = 0\), \(\bar{v}_{rs} = 0\), but \(\bar{v}_{rn} = -1/(2\pi(k+1))\), which is a constant, indicating that slip always occurs at the nut-roller interface. This underscores the importance of minimizing pitch circle mismatch to reduce sliding at the screw-roller side.

To illustrate the application of these models, I consider a numerical example based on a commercial inverted planetary roller screw, similar to those produced by manufacturers like Rollvis. The parameters are: \(R_s = 20 \, \text{mm}\), \(R_r = 5 \, \text{mm}\), \(R_n = 30 \, \text{mm}\), and \(n_s = n_n = 4\). Thus, the radius ratio \(k = R_s / R_r = 4\). The normalized error \(\epsilon\) is varied to study its effects. Using the non-dimensional formulas, I compute key quantities for a range of \(\epsilon\) from -0.01 to 0.01, representing typical mismatch due to deformation. The results are summarized in the following tables to provide a clear overview.

| \(\epsilon\) | \(\theta_{slip} / \theta_n\) | \(\delta_{Total}\) | \(\bar{v}_{cp}\) | \(\bar{v}_{rs}\) | \(\bar{v}_{rn}\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -0.01 | -0.0025 | -0.0011 | -0.02 | -0.00018 | -0.0106 |

| -0.005 | -0.0012 | -0.00055 | -0.01 | -0.000089 | -0.0103 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -0.0100 |

| 0.005 | 0.0012 | 0.00055 | 0.01 | 0.000089 | -0.0097 |

| 0.01 | 0.0025 | 0.0011 | 0.02 | 0.00018 | -0.0094 |

This table shows that as \(\epsilon\) increases, the sliding angle and axial displacement magnitude increase linearly. The circumferential slip velocity \(\bar{v}_{cp}\) is proportional to \(\epsilon\), while the axial slip velocity \(\bar{v}_{rs}\) is small but non-zero for non-zero \(\epsilon\). Notably, \(\bar{v}_{rn}\) remains negative and relatively constant, confirming that slip at the nut-roller interface is inherent. For a specific load case, I estimate the pitch circle mismatch due to contact deformation. Using Hertzian contact theory, as referenced in prior studies on planetary roller screws, under an axial load of 5 kN, the radial contact deformation can be approximately 4.5 μm. Thus, \(\Delta = 4.5 \, \mu\text{m}\) and \(\epsilon = \Delta / R_r = 0.0009\). With \(k=4\), \(\delta_{Total} = 0.0004\). If the total screw travel \(\lambda = 2 \, \text{m}\), then the cumulative axial displacement \(\delta_{rs}^T = 0.0004 \times 2000 \, \text{mm} = 0.8 \, \text{mm}\). This displacement, though small, must be accommodated in the design of the planetary roller screw to prevent binding or loss of engagement.

Furthermore, I explore the sensitivity of these parameters to the radius ratio \(k\). The following table presents how the non-dimensional axial displacement \(\delta_{Total}\) varies with \(k\) for a fixed \(\epsilon = 0.001\).

| k | \(\delta_{Total}\) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.0005 | Moderate displacement |

| 3 | 0.00067 | Increasing with k |

| 4 | 0.00075 | As in the example |

| 5 | 0.0008 | Approaching asymptote |

| 6 | 0.00083 | Slow growth |

This indicates that larger \(k\) (i.e., larger screw relative to roller) leads to slightly higher axial displacement due to mismatch, but the effect diminishes. In practice, designers of planetary roller screw systems can use such tables to select appropriate parameters that minimize unwanted sliding.

The kinematic models also allow for the calculation of power losses due to sliding friction. The frictional power dissipation \(P_f\) at an interface can be estimated as \(P_f = \mu F_n v_{slip}\), where \(\mu\) is the friction coefficient, \(F_n\) the normal force, and \(v_{slip}\) the slip velocity. For the screw-roller interface, using \(v_{cp}\) or \(v_{rs}\), one can assess the contribution to inefficiency. Since the planetary roller screw is often used in high-precision applications, even small losses can accumulate over time, making it essential to control pitch circle mismatch through precise manufacturing and preload adjustments.

In addition to contact deformation, other factors like thermal expansion and wear can exacerbate pitch circle mismatch over the life of the planetary roller screw. Therefore, the kinematic analysis should be part of a broader durability study. For instance, the models can be extended to dynamic conditions where inertial effects become significant at high speeds. The equations of motion for the roller, considering its mass and moment of inertia, could incorporate the sliding forces derived here. This would enable simulation of transient behavior, such as during start-up or load changes, further optimizing the planetary roller screw design for robust performance.

Another aspect is the effect of lubrication on slip velocities. In a well-lubricated planetary roller screw, the friction coefficient may vary with slip speed, leading to complex tribological interactions. The models provide the kinematic inputs for such studies, highlighting the importance of accurate slip velocity calculations. For example, if \(v_{cp}\) exceeds a critical value, it might trigger mixed or boundary lubrication regimes, increasing wear. Hence, minimizing \(\epsilon\) through design, such as using materials with higher stiffness or optimizing tooth profiles, can enhance the longevity of the planetary roller screw mechanism.

To further illustrate the formulas, I present a detailed derivation of the lead relationship. From the definition, the lead \(L\) is the axial advance per revolution. For the nut, \(L_n = n_n p\), and since the pitch is constant, \(p = 2\pi R_r \tan \alpha_r\). Using the condition \(n_s = n_n = k\), and \(\tan \alpha_s = \tan \alpha_r\), we have \(L_s = k p = 2\pi R_s \tan \alpha_s\) and \(L_r = p = 2\pi R_r \tan \alpha_r\). This consistency ensures that in the absence of sliding, the kinematic chain produces the expected motion. However, when sliding occurs, the effective leads at interfaces may differ locally, but the overall system lead remains as derived, demonstrating the robustness of the planetary roller screw architecture.

In conclusion, this study has developed comprehensive kinematic models for the inverted planetary roller screw, accounting for pitch circle mismatch between the roller thread and roller gear. The key findings are:

- The pitch circle mismatch induces relative sliding and axial displacement between the roller and screw in the planetary roller screw system. The sliding angle and axial displacement are directly proportional to the normalized error \(\epsilon\) and depend on the radius ratio \(k\).

- However, this axial displacement does not affect the overall transmission lead of the planetary roller screw. The screw’s axial movement relative to the nut remains equal to the nut lead per revolution, ensuring predictable system output.

- Slip velocities have been derived, showing that the nut-roller interface always experiences axial slip, while the screw-roller slip can be minimized by reducing the pitch circle mismatch. The non-dimensional forms provide insights for design optimization.

- Numerical examples highlight that even small mismatches, such as those from contact deformation under load, can lead to measurable axial displacements (e.g., 0.8 mm over 2 m travel), necessitating design allowances like increased gear tooth width.

These results underscore the importance of controlling pitch circle mismatch in planetary roller screw designs to reduce friction, improve accuracy, and enhance efficiency. Future work could integrate these kinematic models with dynamic and thermal analyses for a holistic approach to planetary roller screw development. By repeatedly considering the planetary roller screw mechanism throughout this analysis, I emphasize its centrality in advanced actuation systems, and the need for precise engineering to overcome challenges like pitch circle mismatch.