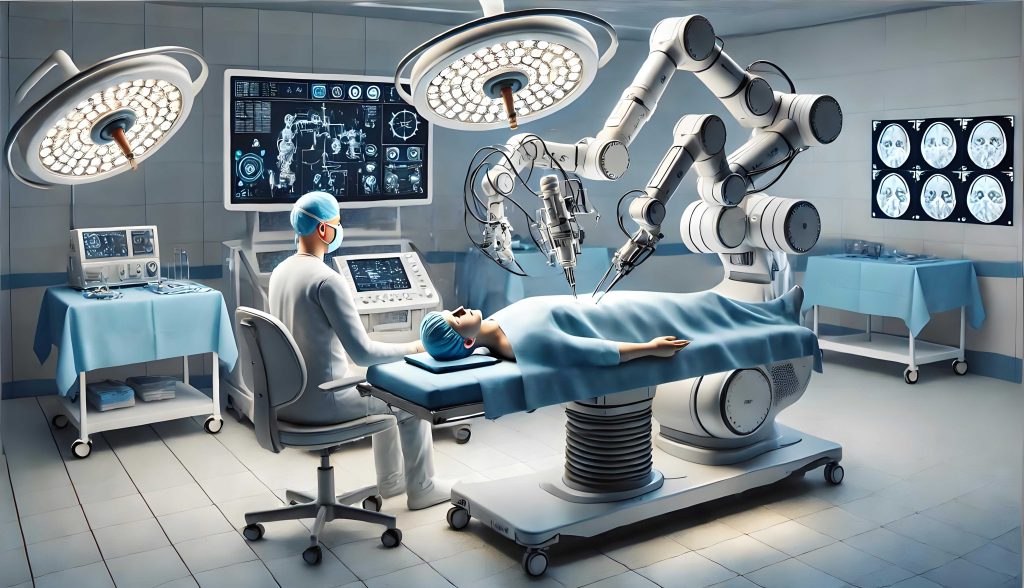

In recent years, the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence has ushered in a new era for healthcare, with medical robots becoming integral to diagnostic, surgical, and therapeutic processes. As a researcher in this field, I have observed how these intelligent systems—equipped with deep learning and autonomous decision-making capabilities—are transforming medical practices. However, this technological leap poses significant challenges to traditional tort law frameworks, particularly in attributing liability for harms caused by medical robots. In this article, I will delve into the complexities of medical robot torts, analyze existing liability approaches, and propose institutional constructs inspired by global initiatives like the European Parliament’s Civil Law Rules on Robotics. My aim is to foster a balanced discourse that encourages innovation while ensuring societal safety.

The integration of medical robots into healthcare systems represents a paradigm shift, driven by algorithms that enable machines to learn from vast datasets and make independent decisions. For instance, surgical medical robots like the da Vinci system have performed thousands of procedures with high precision, while diagnostic medical robots achieve accuracy rates surpassing human experts in areas such as oncology. Despite these benefits, the “black box” nature of AI—where decision-making processes are opaque—introduces unpredictability that complicates liability attribution. From my perspective, this unpredictability stems from the medical robot’s ability to evolve beyond its initial programming, leading to non-human risks that traditional tort law struggles to address. As we embrace this technology, it is crucial to re-evaluate liability pathways to prevent stifling innovation or leaving victims uncompensated.

One of the core issues with medical robot torts is the question of legal personhood. Currently, medical robots are viewed as tools under human control, lacking the consciousness and ethical reasoning inherent to human actors. I argue that granting legal personality to medical robots is premature, as it could disrupt established legal frameworks without solving the underlying problem of unpredictability. Instead, we should focus on refining liability models that account for the medical robot’s autonomous functions. For example, consider a scenario where a medical robot misdiagnoses a patient due to a learned bias not present in its original code. Who should be held responsible—the manufacturer, the healthcare provider, or the medical robot itself? This dilemma highlights the need for nuanced approaches.

To address these challenges, I will explore three primary liability pathways under existing tort law: medical malpractice liability, product liability, and ultra-hazardous activity liability. Each pathway offers insights but falls short in fully accommodating the unique risks posed by medical robots. Below, I present a comparative table summarizing these approaches:

| Liability Approach | Key Elements | Applicability to Medical Robots | Shortcomings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Malpractice Liability | Based on fault of healthcare providers; requires proof of negligence, causation, and harm. | Suitable when medical robots are used as tools by humans; holds institutions accountable for operator errors. | Fails when medical robots act autonomously; unpredictability breaks causation chains and makes negligence hard to prove. |

| Product Liability | Strict liability for defects in design, manufacturing, or warnings; focuses on producers. | Applies as medical robots are products; can cover software flaws or hardware failures. | May inhibit innovation due to high costs; defect exemptions (e.g., state-of-the-art defense) could leave victims unprotected. |

| Ultra-Hazardous Activity Liability | No-fault liability for inherently dangerous activities; emphasizes risk distribution. | Aligns with unpredictability of advanced medical robots; treats risks as societal burdens. | Vague in scope; may not differentiate between human and non-human factors in harm. |

From my analysis, a hybrid model is necessary. In the short term, medical malpractice and product liability can be expanded to cover most medical robot incidents. For instance, if a medical robot causes harm due to a manufacturing defect, product liability should apply; if a healthcare provider misuses the medical robot, malpractice liability is appropriate. However, as medical robots gain more autonomy, we must shift toward a risk-based framework akin to ultra-hazardous liability. I propose using mathematical models to quantify risks associated with medical robots. Let’s define the risk probability $R$ as a function of autonomy level $A$, unpredictability factor $U$, and harm severity $H$:

$$ R = f(A, U, H) = \alpha A + \beta U + \gamma H $$

where $\alpha$, $\beta$, and $\gamma$ are weighting coefficients based on empirical data. This formula can help regulators assess when a medical robot transitions from a tool to a source of non-human risk, triggering stricter liability rules.

The European Parliament’s Civil Law Rules on Robotics provides a valuable blueprint for addressing these issues. I find its emphasis on transparency, equality, and human oversight particularly relevant for medical robots. The rules advocate for principles like “explainability,” where medical robots must provide understandable reasons for decisions, and “black box” recording to trace actions post-incident. In my view, incorporating these into liability frameworks can mitigate the “black box” problem. For example, a medical robot’s algorithm could be designed to log decision pathways, allowing experts to analyze causality in tort cases. Moreover, the European approach suggests a graded liability system: as a medical robot’s autonomy increases, the liability of its trainer decreases, but non-human risks are pooled for collective compensation.

To operationalize this, I recommend establishing specialized regulatory agencies and registration systems for medical robots. A central authority could oversee safety standards, ethical compliance, and liability insurance for medical robots. Below is a proposed institutional framework:

| Institutional Component | Description | Benefits for Medical Robot Torts |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Agency | An independent body to set rules for medical robot development, deployment, and monitoring. | Ensures uniform standards; facilitates liability attribution by maintaining records of medical robot specifications and updates. |

| Registration System | A digital registry tracking each medical robot’s lifecycle, including ownership, usage, and insurance status. | Enables transparency; helps identify liable parties in tort cases involving medical robots. |

| Mandatory Insurance Scheme | Requiring producers or users of medical robots to obtain insurance covering potential harms. | Provides victim compensation without proving fault; spreads risk across the medical robot industry. |

| Compensation Fund | A pooled fund financed by levies on medical robot sales or usage, for cases where insurance is insufficient. | Acts as a safety net; addresses non-human risks from highly autonomous medical robots. |

In developing these institutions, we must prioritize fairness. For instance, insurance premiums for medical robots could be calibrated using risk formulas. Let $P$ be the premium, based on the medical robot’s autonomy score $A_s$ and historical incident rate $I_r$:

$$ P = k \cdot A_s \cdot I_r $$

where $k$ is a constant factor. This incentivizes safer medical robot designs while ensuring fund sustainability. Additionally, I advocate for a举证责任和缓制 (burden of proof mitigation) rule in tort litigation involving medical robots. If a victim demonstrates prima facie causation between a medical robot’s action and harm, the burden should shift to the defendant—such as the manufacturer or hospital—to disprove it. This balances the power asymmetry in complex medical robot cases.

Looking ahead, the evolution of medical robots will likely necessitate continuous legal adaptation. I caution against hastily conferring electronic personhood on medical robots, as this may obscure accountability rather than clarify it. Instead, we should refine liability pathways through iterative policy-making. For example, as medical robots become more integrated into daily healthcare, we might see new tort categories emerge, such as “algorithmic negligence” specific to AI errors. To prepare, I suggest fostering interdisciplinary collaboration between technologists, jurists, and ethicists. Workshops and simulations can test liability models in scenarios where a medical robot makes a life-altering decision autonomously.

In conclusion, the liability for medical robot torts requires a multifaceted approach that blends existing tort principles with innovative institutional constructs. By drawing from the European rules and emphasizing transparency, insurance, and regulation, we can create a system that supports the growth of medical robot technology while protecting societal interests. As I reflect on this topic, it is clear that the medical robot revolution is not just a technical challenge but a legal and ethical one. Through proactive dialogue and adaptive frameworks, we can harness the benefits of medical robots without compromising justice or safety. The journey ahead will demand vigilance, but with thoughtful design, medical robots can become trusted partners in healthcare rather than sources of legal uncertainty.