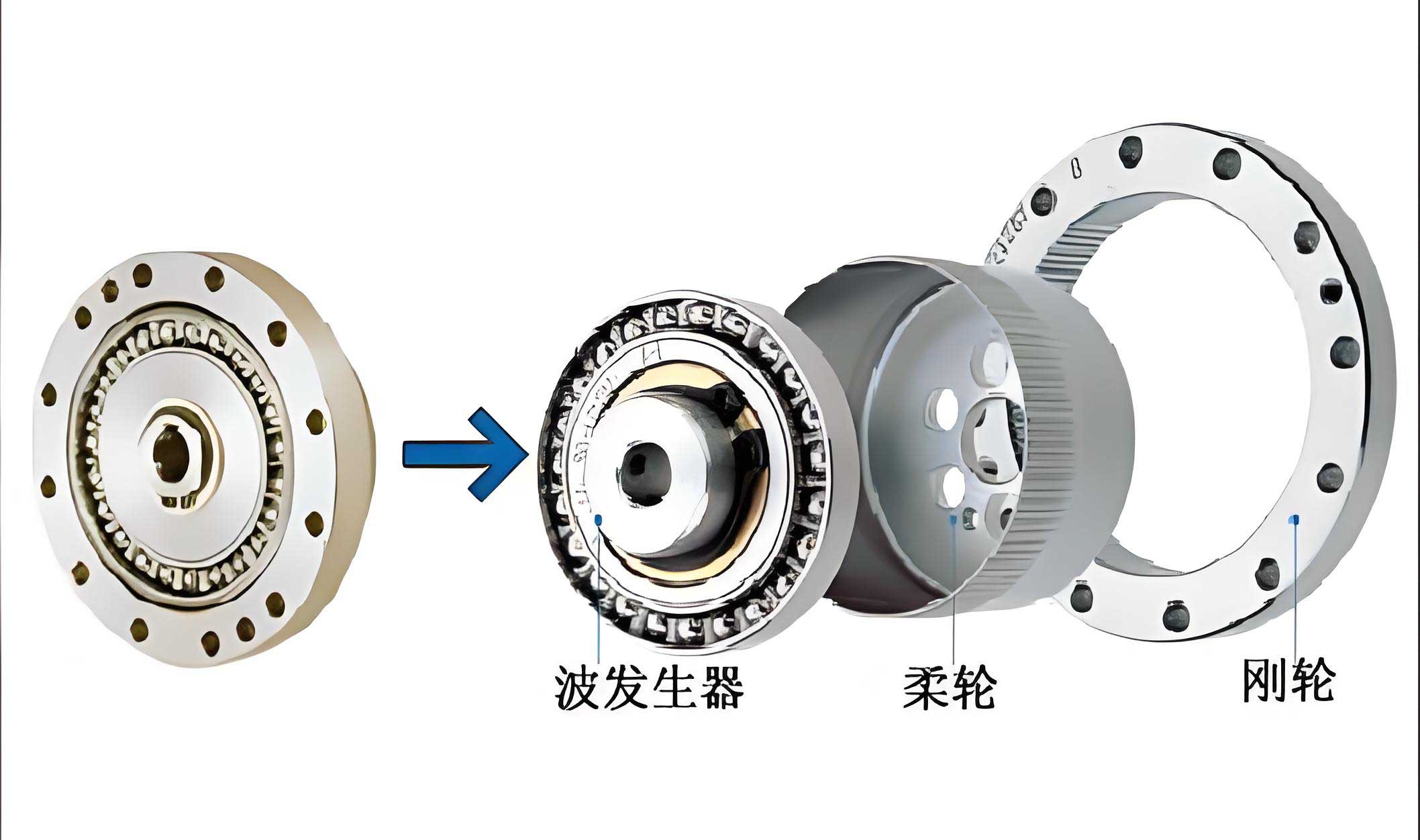

In modern high-performance motion control systems, such as those found in robotics, aerospace attitude platforms, and precision automation, the demand for compact, high-ratio, and low-backlash gearing is paramount. Among the various solutions, the strain wave gear, also commonly referred to as a harmonic drive, has emerged as a critical component. Its unique operating principle, relying on the elastic deformation of a flexible spline (the Flexspline) by a wave generator to mesh with a rigid circular spline (the Circular Spline), offers exceptional advantages including near-zero backlash, high positional accuracy, and compact design. However, as operational speeds increase and performance requirements become more stringent, undesirable dynamic phenomena such as increased vibration amplitude and audible noise become apparent. These vibrations manifest as noticeable radial and circumferential jitter at the output shaft, accompanied by a characteristic beating sound, ultimately degrading the system’s dynamic performance. Therefore, a detailed investigation into the nonlinear dynamic characteristics of the strain wave gear transmission system is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for advancing their application in demanding fields.

The dynamic behavior of a strain wave gear system is inherently complex and dominated by several intrinsic nonlinearities. These include the kinematic transmission error arising from manufacturing imperfections, the highly nonlinear torsional stiffness characteristic of the compliant Flexspline, and the presence of backlash in the gear mesh. Early dynamic models often simplified these aspects, treating stiffness as linear or ignoring the hysteretic nature of the torque-deflection relationship. My research focuses on developing a comprehensive nonlinear torsional vibration model that rigorously incorporates these factors. The goal is to create a predictive tool that not only simulates the system’s response under various operating conditions but also identifies the primary sources of excitation, thereby guiding design, manufacturing, and assembly processes towards minimized vibration.

The cornerstone of an accurate dynamic model is a precise representation of the excitation sources. In a strain wave gear system, the primary kinematic excitation is the transmission error (TE), defined as the difference between the actual output position and the theoretically ideal output position for a given input. Previous models often described TE using Fourier series derived from experimental measurements, lacking a direct physical link to the actual geometric error sources within the gearbox. In my work, I derive the TE formulation from the fundamental meshing mechanics of the strain wave gear, considering the contribution of individual error sources under the assumptions of independent action and superposition. For a strain wave gear with a fixed Circular Spline, the composite transmission error $\theta_e(t)$, in arcseconds, can be expressed as:

$$

\theta_e(t) = \frac{1}{2N} \left[ \sum_{m=1}^{P} \Delta F_{im} \sin(\omega_4 t – m\zeta_2 – \xi_2 + \phi_m) + \Delta S_{fix} \sin(\omega_2 t + \phi_4) + \sum_{j=1}^{Q} \Delta f_{ij} \sin(\omega_3 t + \varphi_j) + \frac{1}{\cos\alpha_n} \left( \sum_{k=1}^{6} T_{1k} \sin(\omega_1 t + \vartheta_k) + \frac{1}{i \cos\alpha_n} \sum_{l=1}^{14} T_{1l} \sin(\omega_4 t + \varrho_l) \right) \right] \cdot \frac{412.5296}{d_w}

$$

Where $d_w$ is the pitch diameter of the Flexspline, $\alpha_n$ is the nominal pressure angle, $i$ is the gear ratio, and $N$ is the average number of tooth pairs in simultaneous contact. The frequencies $\omega_1, \omega_2, \omega_3, \omega_4$ are related to the wave generator rotational speed $\Omega_H$ ($\omega_4 = \Omega_H$, $\omega_2 = U\Omega_H$, $\omega_3 = U Z_2 \Omega_H$, $\omega_1 = U(1+1/i)\Omega_H$), with $U$ being the wave number (typically 2) and $Z_2$ the number of teeth on the Circular Spline. The terms $\Delta F_{im}$ and $\Delta f_{ij}$ represent the tangential composite errors and base pitch errors of the Flexspline and Circular Spline, respectively. The coefficients $T_{1k}$ and $T_{1l}$ aggregate various assembly and component errors, such as radial runouts of shafts and bearings, fitting clearances, and bearing radial play. This formulation is powerful because each term corresponds directly to a specific physical error source (e.g., $\Delta S_{fix}$ is the misalignment of the housing), allowing for targeted sensitivity analysis. The key error sources and their corresponding frequency contributions are summarized in the table below.

| Error Category | Representative Sources | Primary Frequency Component | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexspline Manufacturing | Tangential composite error $\Delta F_{i1}$, Base pitch error $\Delta f_{i1}$ | $\omega_4, 2\omega_4, \omega_3$ | Imperfections in the flexspline tooth geometry. |

| Circular Spline Manufacturing | Tangential composite error $\Delta F_{i3}$, Base pitch error $\Delta f_{i2}$ | $\omega_2$ | Imperfections in the rigid circular spline tooth geometry. |

| Output Side Assembly | Output shaft radial runout ($S_{fa1}$), Bearing clearance ($C_{fa2}, C_{obh2}$), Bearing radial play ($E_{ob1}$) | $\omega_1 = U(1+1/i)\Omega_H$ | Errors in the output shaft-bearing-housing assembly. |

| Input/Wave Generator Assembly | Cam profile error ($S_{wC}$), Flexible bearing radial play ($E_{wfb2}$), Input bearing clearance ($C_{wab1}$) | $\omega_4 = \Omega_H$ | Errors in the wave generator and input shaft assembly. |

| Housing Misalignment | Housing bore misalignment $\Delta S_{fix}$ | $\omega_2 = U\Omega_H$ | Misalignment between the housing features for the circular spline and bearings. |

The second major nonlinearity is the torsional stiffness $K_{HD}$ of the strain wave gear assembly. Unlike conventional gear trains, the strain wave gear exhibits a pronounced hysteresis loop in its torque versus angular deflection characteristic. This is primarily due to the elastic deformation and friction within the Flexspline, the wave generator bearing, and the tooth contacts. Simply using a constant stiffness value is insufficient for dynamic analysis. Based on experimental torque-angle data, I have employed a piecewise polynomial approach. The loading and unloading curves are separately fitted with third-order polynomials. The instantaneous torsional stiffness is then obtained as the derivative of these fitted curves with respect to the angular deflection $x$:

Loading Stiffness (increasing torque): $$ K_{2}(x) = A_2 x^2 + B_2 x + C_2 $$

Unloading Stiffness (decreasing torque): $$ K_{1}(x) = A_1 x^2 + B_1 x + C_1 $$

Here, $A_{1,2}$, $B_{1,2}$, and $C_{1,2}$ are coefficients obtained from the experimental data fitting, with units consistent with N·m/arcsec³, N·m/arcsec², and N·m/arcsec, respectively. The transition between these curves depends on the history of the motion (whether the system is being driven further into load or is coming back), introducing a memory-dependent nonlinearity into the system dynamics.

The third nonlinear element is the backlash or lost motion, represented by a dead-zone function. The total mechanical backlash $2\beta_j$ and the system’s elastic hysteresis $\Delta_t$ define a piecewise function for the restoring force $f(\delta)$:

$$

f(\delta) =

\begin{cases}

\delta – \beta_j & \text{if } \delta > \beta_j \\

0 & \text{if } -\beta_j – \Delta_t/2 \leq \delta \leq \beta_j + \Delta_t/2 \\

\delta + \beta_j & \text{if } \delta < -\beta_j

\end{cases}

$$

where $\delta$ is the dynamic transmission error (the difference between the actual and kinematically enforced relative displacement). The central dead-zone of width $(\beta_j + \Delta_t/2)$ represents regions where the gear teeth are not in contact and the effective stiffness is zero.

Integrating these nonlinearities, I establish a two-inertia torsional vibration model for the strain wave gear system. The model consists of the input inertia $J_1$ (motor rotor, wave generator) and the output inertia $J_0$ (load, output shaft), connected through the nonlinear strain wave gear element characterized by the stiffness $K_{HD}$, backlash function $f(\delta)$, and transmission error excitation $\theta_e(t)$. Applying Newton’s second law and defining the dynamic transmission error as $\delta = \theta_0 – \theta_1 / i – \theta_e(t)$ (where $\theta_0$ and $\theta_1$ are the absolute rotations of the output and input sides, respectively), the equation of motion is derived. After algebraic manipulation and assuming an equivalent viscous damping coefficient $C_{io} = 2\xi \sqrt{J_{dl} \bar{K}}$ (where $\bar{K}$ is an average stiffness and $\xi$ is the damping ratio), the governing nonlinear differential equation for the dynamic transmission error $\delta$ is:

$$

J_{dl}\ddot{\delta} + C_{io}(\dot{\delta} – \dot{\theta_e}) + K_{HD} \cdot f(\delta) = -J_{dl}\left[ \frac{1}{J_0}(T_L + T_{iL}\sin(\omega_{L}t)) + \frac{1}{i J_1}(T_d + T_{id}\sin(\omega_{d}t)) \right]

$$

Here, $J_{dl} = (i^2 J_1 J_0) / (i^2 J_1 + J_0)$ is the equivalent lumped inertia of the system. The right-hand side represents the forcing due to mean and fluctuating load torques ($T_L$, $T_{iL}\sin(\omega_{L}t)$) on the output and mean and fluctuating drive torques ($T_d$, $T_{id}\sin(\omega_{d}t)$) on the input. The term $C_{io}\dot{\theta_e}$ represents a damping force proportional to the rate of change of the kinematic transmission error.

This equation is a strongly nonlinear second-order differential equation due to the piecewise-defined stiffness $K_{HD}$ and dead-zone function $f(\delta)$. Analytical solutions are intractable, necessitating numerical methods for simulation and analysis. I developed a dedicated simulation software using a variable-step fourth-order Runge-Kutta integration scheme. The algorithm includes logic to track the state of the system (loading or unloading) and the engagement condition (inside or outside the backlash zone) to correctly switch between the respective stiffness polynomials $K_1(x)$ and $K_2(x)$ at each integration step. This software serves as a virtual test bench for exploring the nonlinear dynamics of the strain wave gear system.

To validate the model and observe real-world dynamics, I conducted extensive experimental tests on a commercial strain wave gear unit (similar to an XB-80-134H type). The test setup involved driving the input shaft with a servo motor across a wide speed range (from 100 to 2700 rpm) while the output was kept under no load. An accelerometer mounted on the output housing captured the vibration response, which was processed to obtain velocity and displacement time histories via integration. The key observations from the experimental data were:

- Amplitude Growth and Jump Phenomenon: As the input speed increased, the vibration amplitude generally grew. More importantly, at high speeds (around 2600-2700 rpm), the response amplitude exhibited a sudden, step-like increase, a classic signature of a nonlinear jump resonance, akin to the behavior of a hardening spring system.

- Spectral Content: Frequency analysis of the response at different speeds revealed distinct peaks. A particularly noticeable peak was found at a frequency corresponding to $2Z_2 f_H$ (where $f_H$ is the wave generator rotational frequency in Hz). However, the amplitude of this very high-frequency component was relatively small compared to lower-frequency components.

Using the simulation software with parameters derived from the test unit’s specifications, measured stiffness data, and estimated error magnitudes, I performed numerical simulations. The results successfully replicated key nonlinear phenomena observed in the experiment. The time-domain response showed complex, non-harmonic oscillations. The phase portrait (plot of velocity versus displacement) displayed a tangled, non-repeating trajectory, and the Poincaré section (sampling the phase portrait at the period of the fundamental excitation) showed a cloud of points rather than a finite set. These are strong indicators of chaotic vibration under the specific simulated operating conditions, driven by the interplay of transmission error excitation, nonlinear stiffness, and backlash.

A crucial aspect of this research is to decompose the complex dynamic response and attribute its energy to specific physical error sources. By correlating the spectral peaks from both experiments and simulations with the frequency terms in the transmission error model, I can assess the contribution of different error categories. The analysis clearly shows that the most significant contributions to the dominant low-frequency vibration come from error terms with frequencies related to $\omega_1 = U(1+1/i)\Omega_H$ and $\omega_2 = U\Omega_H$.

| Identified Spectral Peak (from Exp/Sim) | Theoretical TE Frequency | Major Contributing Error Sources | Relative Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~44-45 Hz (at ~2680 rpm input) | $\omega_4 = \Omega_H$ | Wave generator assembly errors (cam profile, flexible bearing play, input bearing clearances). | Low. Amplitude is divided by gear ratio $i$ when reflected to output. |

| ~89 Hz | $2\omega_4 = 2\Omega_H$ | Second harmonic of wave generator errors, certain housing effects. | Moderate. Observable peak in spectrum. |

| ~90 Hz | $\omega_1 = U(1+1/i)\Omega_H \approx 2\Omega_H$ | Output side assembly errors (output shaft runout, bearing clearances and play). | Very High. This is often the dominant peak in the spectrum. |

| ~24120 Hz | $2Z_2 f_H = 2Z_2 \Omega_H / 2\pi$ | Tooth mesh frequency harmonics (e.g., from tooth spacing errors). | Low. High frequency but low energy contribution to output vibration. |

This diagnostic capability is a primary outcome of the model. It shifts the focus from merely observing vibration to understanding its root causes. The conclusion is that to minimize dynamic response in a strain wave gear system, the primary control objectives during design, manufacturing, and assembly should be:

1. Output-side assembly precision: Minimizing radial runout of the output shaft,严格控制轴承与轴和座孔的配合间隙 (strictly controlling bearing fits and clearances on the output side), and specifying bearings with minimal radial play.

2. Flexspline and Circular Spline quality: Controlling the tangential composite error and base pitch error of both the Flexspline and the Circular Spline.

3. Housing alignment: Ensuring the concentricity and alignment of the housing bores for the Circular Spline and the output bearings.

In summary, the nonlinear dynamics of a strain wave gear system are governed by a synergy of kinematic error excitation, memory-dependent stiffness hysteresis, and discontinuous backlash. The physics-based transmission error model I developed provides a direct mapping from component-level imperfections to system-level dynamic excitation. Coupled with a numerically solved nonlinear dynamic model incorporating piecewise stiffness, this framework offers a powerful tool for both the analysis and design of strain wave gear systems. The insights gained, particularly the identification of output-side assembly errors as a dominant excitation source, provide clear guidance for precision engineering practices aimed at achieving smoother operation and higher performance in applications reliant on this exceptional yet dynamically complex technology. Future work will involve extending the model to include more detailed friction models and validating it against a broader range of operating conditions and loading scenarios.