In the field of precision mechanical transmission, the strain wave gear, often referred to as harmonic drive, represents a pivotal technology for applications requiring high reduction ratios, compact design, and accurate motion control. However, the design process of a strain wave gear is inherently complex due to its reliance on the elastic deformation of a flexible spline, or flexspline, to transmit motion. Traditional design methodologies, while functional, often yield suboptimal parameters, leading to inefficiencies, increased material costs, and limitations in performance, such as gear tooth interference, fatigue failure from torsional and bending stresses, high starting torque, excessive heat generation, and restricted lower limits of transmission ratios. To address these challenges, an advanced optimization approach is imperative. In this article, I explore the application of genetic algorithms (GAs) to the parametric optimization design of strain wave gear transmissions. By leveraging the global search capabilities of GAs, I aim to develop a robust framework for determining optimal design variables that minimize material volume and maximize transmission efficiency, thereby enhancing the overall performance and economic viability of strain wave gear systems.

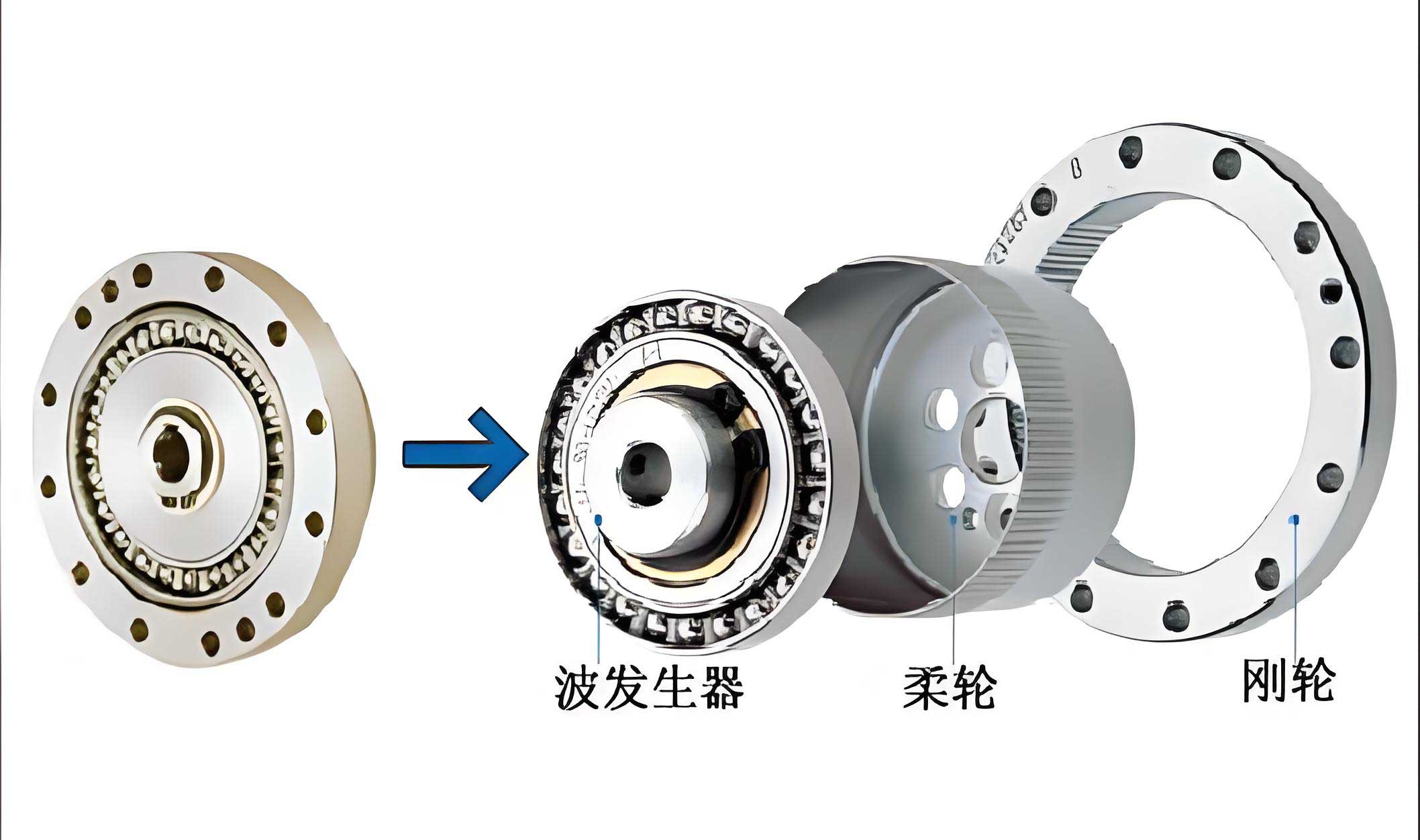

The core principle of a strain wave gear transmission revolves around three primary components: a wave generator, a flexspline (or柔轮), and a circular spline (or刚轮). The wave generator, typically an elliptical cam with a flexible bearing, induces controlled elastic deformation in the flexspline, causing its teeth to engage and disengage with those of the circular spline in a progressive wave-like motion. This unique mechanism allows for high reduction ratios in a compact envelope. However, the success of this design hinges on the careful selection of geometric and material parameters. Key design variables include the module (m), the length of the flexspline barrel (L), the tooth width (b), and the wall thickness of the flexspline barrel (δ). These parameters directly influence other critical variables such as the number of teeth on the flexspline (Z1) and circular spline (Z2), pitch diameters (D1, D2), and pressure angle (α). Given that the transmission ratio (i) is often specified based on application requirements, the independent design variables can be succinctly represented as:

$$ X = [\delta, m, b, L]^T = [X_1, X_2, X_3, X_4]^T $$

Optimizing these variables is a multi-objective endeavor. In practical engineering, reducing material usage to lower costs and improving transmission efficiency are paramount. Therefore, I define two primary objective functions: minimizing the volume of the flexspline (F1(X)) and maximizing the transmission efficiency (F2(X)). The volume minimization directly correlates with material savings and weight reduction, while efficiency maximization enhances energy utilization and reduces thermal issues. The multi-objective nature of this problem necessitates a careful balance, as these goals may conflict. For instance, reducing wall thickness might decrease volume but could compromise strength and efficiency.

The strain wave gear transmission operates through a fascinating interplay of elasticity and kinematics. The wave generator deforms the flexspline into an elliptical shape, causing meshing between the flexspline and circular spline at two diametrically opposite regions. As the wave generator rotates, these meshing zones propagate, resulting in a relative rotation between the flexspline and circular spline. The reduction ratio is determined by the difference in tooth counts between the two splines. However, this elastic deformation introduces significant mechanical complexities. The flexspline undergoes cyclic stress variations, leading to fatigue concerns. Moreover, geometric constraints must be satisfied to prevent tooth interference, such as profile overlap interference and fillet interference, which can occur if parameters are not properly selected. The following table summarizes key geometric relationships derived from the primary design variables for a typical strain wave gear configuration.

| Parameter | Symbol | Relationship or Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Flexspline Number of Teeth | Z1 | Function of module m and pitch diameter D1: $Z_1 = \frac{D_1}{m}$ |

| Circular Spline Number of Teeth | Z2 | $Z_2 = Z_1 + 2n$, where n is wave number (typically 2) |

| Pitch Diameter of Flexspline | D1 | Often derived from design constraints; $D_1 \approx m Z_1$ |

| Pitch Diameter of Circular Spline | D2 | $D_2 \approx m Z_2$ |

| Wave Generator Dimensions | d | Wave height, related to deformation and module |

| Transmission Ratio | i | $i = -\frac{Z_1}{Z_2 – Z_1}$ for standard configuration |

Given the mixed discrete-continuous nature of the design variables—where module m is typically a discrete value from standard series, while L, b, and δ are continuous—the optimization problem falls into the category of mixed discrete variable nonlinear programming with multiple objectives. Traditional gradient-based optimization methods, such as the complex method, random direction method, or penalty function methods, often struggle with such problems due to their propensity to converge to local optima and difficulties in handling discrete variables and multiple peaks in the objective landscape. In contrast, genetic algorithms, inspired by the principles of natural selection and genetics, offer a robust alternative. GAs operate on a population of candidate solutions, applying operators like selection, crossover, and mutation to evolve solutions over generations. This population-based approach enables a global search across the design space, making GAs particularly effective for solving complex, multimodal, and mixed-variable optimization problems. Their ability to handle non-differentiable functions and discrete variables without requiring derivative information aligns perfectly with the challenges posed by strain wave gear design optimization.

To formalize the optimization problem, I establish the mathematical model. The design variable vector X is as defined earlier. The objective functions are formulated as follows. The volume of the flexspline, which is approximated as a cylindrical shell with teeth, can be expressed as:

$$ F_1(X) = \text{Volume} \approx \frac{\pi}{4} \left[ (D_1 + 2\delta)^2 – D_1^2 \right] L + \text{tooth volume contribution} $$

For simplicity and focusing on the barrel, the volume can be simplified to a function of δ, D1, and L. However, a more precise model might include tooth geometry. The transmission efficiency F2(X) is a function of friction losses, material properties, and geometric parameters, often derived from empirical or analytical models considering sliding and rolling friction in the mesh. A common approximation for efficiency η is:

$$ \eta = 1 – \frac{P_{\text{loss}}}{P_{\text{in}}} $$

where Ploss includes losses from tooth mesh, bearing friction, and windage. For optimization, I aim to maximize η, which is equivalent to minimizing 1 – η. Thus, I define F2(X) = 1 – η, so minimizing F2(X) maximizes efficiency. The multi-objective optimization problem is then:

$$ \text{Minimize: } \mathbf{F}(X) = [F_1(X), F_2(X)] $$

subject to constraints. The constraints arise from geometric, strength, and performance requirements. Key constraints include:

- Geometric Constraints: To prevent tooth interference, conditions such as minimum tooth tip clearance, contact ratio limits, and interference avoidance formulas must be satisfied. For example, the contact ratio should be greater than 1.2 to ensure smooth transmission.

- Strength Constraints: The flexspline must withstand cyclic stresses without fatigue failure. The torsional stress τ and bending stress σ must be below allowable limits. Fatigue safety factors are applied based on material properties (e.g., for material like 20Cr2Ni4A).

- Stability Constraints: The thin-walled flexspline barrel must resist buckling under torsional loads. The critical shear stress for buckling τ_cr must exceed the applied shear stress τ_γ by a safety margin.

- Design Variable Bounds: Practical limits on variables, e.g., module m must be from a standard series (e.g., 0.5, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0 mm), δ must be above a minimum for manufacturability, b and L within reasonable ranges.

These constraints can be expressed as inequality constraints:

$$ g_j(X) \leq 0, \quad j = 1, 2, \ldots, J $$

where J is the number of constraints. For instance, a fatigue constraint might be:

$$ g_1(X) = \frac{\tau_{\text{max}}}{\tau_{\text{allowable}}} – 1 \leq 0 $$

and a buckling constraint:

$$ g_2(X) = \frac{\tau_{\gamma}}{\tau_{cr}} – 1 \leq 0 $$

Genetic algorithms inherently operate on unconstrained problems. Therefore, to handle constraints, I employ a penalty function method, specifically an exterior penalty function approach. This method transforms the constrained problem into an unconstrained one by adding penalty terms to the objective function for constraint violations. The augmented objective function becomes:

$$ \Phi(X) = w_1 F_1(X) + w_2 \cdot 1000 \cdot F_2(X) + \sigma \sum_{j=1}^{J} \left[ \max(0, g_j(X)) \right]^2 $$

Here, w1 and w2 are weighting factors to balance the two objectives. Since F1(X) (volume) and F2(X) (efficiency-related) may differ in magnitude, I scale F2(X) by 1000 to ensure both objectives contribute comparably to the total fitness. The term σ is a penalty coefficient, typically a large positive number (e.g., 10^6). The sum over constraints penalizes any violation; if all constraints are satisfied (g_j(X) ≤ 0), the penalty term is zero. This method drives the solution toward feasibility while optimizing the objectives. The choice of σ is crucial; too small may allow infeasible solutions, too large may cause numerical issues. In practice, I use a dynamically increasing σ over generations to ensure convergence to a feasible optimum.

The genetic algorithm implementation involves several steps. First, I encode the design variables into chromosomes. For mixed variables, I use a real-valued representation for continuous variables (δ, b, L) and integer representation for discrete variables (m). The initial population is randomly generated within specified bounds. Each individual’s fitness is evaluated using the augmented objective function Φ(X). Selection is performed using tournament selection or roulette wheel selection based on fitness. Crossover (with probability Pc) blends parents’ genes; for real variables, simulated binary crossover (SBX) is used, and for discrete variables, single-point crossover. Mutation (with probability Pm) introduces random changes; for real variables, polynomial mutation, and for discrete variables, random resetting. Elitism is often incorporated to preserve the best solutions across generations. The algorithm iterates until a termination criterion is met, such as a maximum number of generations or convergence of fitness values.

To demonstrate the efficacy of this approach, I conduct a detailed case study based on a typical strain wave gear transmission application. The design specifications are as follows: output torque T = 600 N·m, transmission ratio i = 100, standard pressure angle α0 = 20°, gear manufacturing accuracy grade 7, flexspline material 20Cr2Ni4A. The wave generator is a cam-type with a flexible rolling bearing, and its speed is 3000 rpm. The initial design, derived from conventional methods, has parameters: δ = 2.0 mm, m = 0.8 mm, b = 28 mm, L = 160 mm. The goal is to optimize these parameters using the GA framework.

I set up the genetic algorithm with the following parameters: population size = 500, maximum generations = 500, crossover probability Pc = 0.8, mutation probability Pm = 0.02. The weighting factors are chosen as w1 = 1 and w2 = 1, emphasizing both volume and efficiency equally. The penalty coefficient σ is set to 10^6. The design variable bounds are: δ ∈ [1.5, 3.0] mm, m ∈ {0.5, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0} mm (discrete set), b ∈ [20, 40] mm, L ∈ [120, 200] mm. The objective functions are computed using analytical models for volume and efficiency. Volume F1(X) is calculated as the volume of the flexspline barrel plus teeth approximation. Efficiency F2(X) is derived from empirical formulas considering mesh friction losses and bearing losses, with an initial efficiency around 85% for the baseline design.

The optimization process evolves over 500 generations. The convergence plot shows the best fitness decreasing steadily, indicating improvement. After completion, the optimal design variables are obtained:

$$ X_{\text{opt}} = [\delta = 1.921 \text{ mm}, m = 0.801 \text{ mm}, b = 25.610 \text{ mm}, L = 153.201 \text{ mm}] $$

Note that m is reported as 0.801 mm due to continuous optimization, but in practice, it would be snapped to the nearest discrete value (0.8 mm). Comparing with the initial design, the changes are: δ reduced by 3.95%, m essentially unchanged, b reduced by 8.53%, and L reduced by 4.37%. The impact on objectives is significant. The flexspline volume decreases by approximately 7.94%, indicating material savings. The transmission efficiency improves by 0.85%, reaching around 85.85%. While the efficiency gain seems modest, in high-precision applications, even small improvements can reduce heat generation and energy consumption over the operational lifespan.

| Parameter | Initial Design | Optimized Design | Percentage Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall Thickness δ (mm) | 2.000 | 1.921 | -3.95% |

| Module m (mm) | 0.800 | 0.801 (≈0.8) | ~0% |

| Tooth Width b (mm) | 28.000 | 25.610 | -8.53% |

| Barrel Length L (mm) | 160.000 | 153.201 | -4.37% |

| Flexspline Volume (approx. cm³) | Calculated: V_init | Calculated: V_opt | -7.94% |

| Transmission Efficiency η | 85.00% | 85.85% | +0.85% |

To validate the optimized design, I perform strength and stability analyses. For fatigue strength, the safety factor against torsional fatigue is computed based on the maximum shear stress and the endurance limit of 20Cr2Ni4A. The initial design has a safety factor s_τ ≈ 2.0, while the optimized design yields s_τ ≈ 2.05, a slight improvement of 2.5%. This indicates that despite the reduction in wall thickness, the optimized parameters maintain or even enhance fatigue resistance due to better stress distribution. For barrel stability under torsion, the ratio of critical buckling shear stress to applied shear stress is evaluated. The initial design has τ_cr / τ_γ = 4.698, whereas the optimized design achieves τ_cr / τ_γ = 5.206, an improvement of 10.8%. This significant enhancement in stability margin demonstrates that the optimization effectively mitigates buckling risks, which is crucial for the reliable operation of the strain wave gear.

The results underscore the effectiveness of genetic algorithms in navigating the complex design space of strain wave gear transmissions. By considering multiple objectives and constraints simultaneously, the GA identifies a Pareto-optimal solution that balances material economy and performance. The ability of GAs to handle mixed variables is particularly advantageous; for instance, the module m is naturally treated as discrete, avoiding the need for post-processing rounding that might degrade optimality. Moreover, the global search capability prevents entrapment in local optima, which is common in traditional methods when dealing with nonlinear constraints and multiple peaks.

Further analysis reveals insights into the sensitivity of design variables. For example, the wall thickness δ has a strong influence on both volume and strength; reducing it decreases volume but must be compensated by adjustments in other parameters to maintain strength. The tooth width b directly affects load capacity and efficiency; its reduction in the optimized design suggests that the initial value was conservative. The barrel length L impacts overall dimensions and stiffness; its optimization contributes to compactness. The module m, being discrete, shows less variation, but its selection is critical for tooth geometry and interference avoidance. The following table summarizes the influence trends based on the optimization outcomes.

| Design Variable | Impact on Volume | Impact on Efficiency | Impact on Strength/Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall Thickness (δ) | High: Direct proportionality | Moderate: Affects stiffness and losses | High: Critical for fatigue and buckling |

| Module (m) | Moderate: Affects tooth dimensions | High: Influences mesh friction and geometry | High: Determines tooth strength and interference |

| Tooth Width (b) | Moderate: Linear effect on tooth volume | Moderate: Wider teeth may increase friction | High: Directly related to load capacity |

| Barrel Length (L) | High: Linear effect on barrel volume | Low: Minor effect on efficiency | Moderate: Affects buckling length and stiffness |

In terms of computational efficiency, the genetic algorithm required approximately 500 generations with a population of 500, resulting in 250,000 function evaluations. While this may seem computationally intensive, modern computing resources and parallelization techniques can significantly reduce runtime. Moreover, the quality of the solution justifies the effort, especially for custom strain wave gear designs where performance and cost are critical. Compared to traditional trial-and-error or gradient-based methods, the GA provides a systematic and automated approach that can explore a broader design space, leading to more innovative and optimal configurations.

The application of genetic algorithms to strain wave gear optimization also opens avenues for further enhancements. For instance, multi-objective GAs like NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II) can be employed to generate a Pareto front of solutions, allowing designers to choose based on specific trade-offs between volume and efficiency. Additionally, integrating finite element analysis (FEA) for accurate stress and deformation calculations within the fitness evaluation could improve fidelity, albeit at higher computational cost. Machine learning surrogates could be used to approximate expensive simulations, speeding up the optimization process. These advanced techniques could further refine the design of strain wave gear transmissions for emerging applications in robotics, aerospace, and precision machinery.

In conclusion, the integration of genetic algorithms into the parametric design of strain wave gear transmissions proves to be a powerful and effective methodology. By addressing the mixed discrete-continuous, multi-objective, and constrained nature of the problem, GAs enable the discovery of optimal design parameters that enhance material utilization, improve transmission efficiency, and ensure mechanical integrity. The case study demonstrates tangible benefits: a reduction in flexspline volume by nearly 8%, a slight but valuable increase in efficiency, and improved fatigue and stability safety factors. This approach not only surpasses traditional design methods in terms of optimality but also offers a flexible framework adaptable to various design specifications. As strain wave gear technology continues to evolve for high-performance applications, genetic algorithm-based optimization will play a crucial role in advancing design efficiency and performance, providing engineers with a robust tool to overcome the inherent complexities of these sophisticated transmission systems. The success of this method underscores the synergy between computational intelligence and mechanical engineering, paving the way for more innovative and sustainable designs in the future.