In recent years, the fruit and vegetable industry has experienced rapid growth, leading to increased demand for efficient harvesting solutions. As labor costs rise and shortages become more prevalent, the development of agricultural robots, particularly harvesting robots, has gained significant attention. The end effector, as a critical component of these robots, directly interacts with fruits and is responsible for detaching them from plants. However, current end effector systems often suffer from inefficiencies in PID control parameter tuning, nonlinear characteristics, and insufficient anti-interference capabilities, making precise fruit grasping challenging. In this study, we address these issues by proposing a genetic algorithm (GA)-optimized fuzzy PID control strategy to enhance the performance of the harvesting end effector. This approach aims to improve transient response speed, control accuracy, and stability, ensuring reliable and damage-free fruit harvesting.

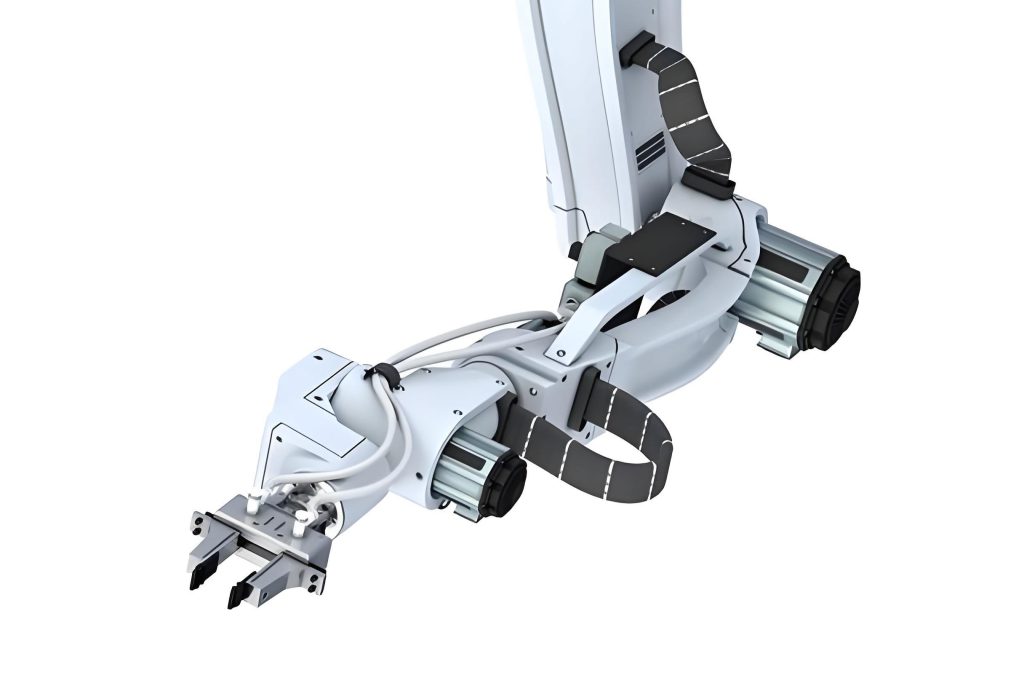

The end effector used in this research features a flexible design with tactile sensors integrated into the grippers. This configuration allows for adaptive grasping and force feedback, which is essential for handling delicate fruits. The dynamics of the end effector are modeled to understand its behavior during interaction with objects. We begin by establishing the kinetic model using the Lagrange formulation, which describes the relationship between joint variables, inertial forces, and external contacts. The equation is given as:

$$ M(q) \frac{d^2q}{dt^2} + C\left(q, \frac{dq}{dt}\right) \frac{dq}{dt} + G(q) + F_f\left(q, \frac{dq}{dt}\right) = \tau – J^T f $$

where \( M \) is the inertia matrix, \( q \) represents joint variables, \( C \) denotes the centrifugal and Coriolis force matrix, \( G \) is the gravity term, \( F_f \) is the friction torque vector, \( \tau \) is the driving force, \( J^T \) is the Jacobian matrix, and \( f \) is the environmental contact force. This model forms the basis for analyzing the end effector’s motion and force interactions during harvesting tasks.

To further describe the contact between the end effector and the fruit, we employ a mass-spring system analogy. The interaction force can be expressed as:

$$ f = m \frac{d^2x}{dt^2} + k x + f_{\text{disturbance}} $$

Here, \( m \) is the mass of the object, \( x \) is the spring displacement, \( k \) is the system stiffness, and \( f_{\text{disturbance}} \) accounts for external disturbances. By combining this with the kinetic model, we derive the servo control rules for the gripper, leading to a closed-loop error equation. Through Laplace transform, the transfer function between the driving force and the output force of the end effector is obtained:

$$ G(s) = \frac{T(s)}{F(s)} = \frac{k_e + k_{ec} / x}{m s^2 + k s + k_e + k_{ec}} $$

where \( T(s) \) is the output force of the end effector, \( F(s) \) is the motor driving force, \( s \) is the complex variable in Laplace transform, \( k_e \) is the stiffness coefficient, and \( k_{ec} \) is the damping coefficient. This transfer function is crucial for designing the control system to achieve precise force tracking.

The control methodology involves a fuzzy PID controller, which integrates fuzzy logic with traditional PID control to enable adaptive parameter adjustment. This is particularly beneficial for the nonlinear and time-varying dynamics of the harvesting end effector. The fuzzy PID controller uses the error \( E \) and the error change rate \( E_c \) as inputs, which are fuzzified based on predefined membership functions. The output variables \( \Delta K_p \), \( \Delta K_i \), and \( \Delta K_d \) represent adjustments to the PID parameters. The membership functions for \( E \) and \( E_c \) are defined over the universe of discourse \(\{-3, 3\}\), while the output universe is \(\{-1, 1\}\). The fuzzy rules are designed to map input conditions to output adjustments, ensuring robust control under varying operational scenarios.

The PID control algorithm is formulated as:

$$ u(t) = K_p E(t) + K_i \int_0^t E(t) dt + K_d \frac{dE(t)}{dt} $$

where \( u(t) \) is the control output, \( E(t) = r(t) – y(t) \) is the error between the reference signal \( r(t) \) and the system output \( y(t) \), and \( K_p \), \( K_i \), and \( K_d \) are the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively. The fuzzy controller modifies these gains dynamically:

$$ K_p = K_{p0} + \Delta K_p, \quad K_i = K_{i0} + \Delta K_i, \quad K_d = K_{d0} + \Delta K_d $$

Here, \( K_{p0} \), \( K_{i0} \), and \( K_{d0} \) are the initial PID parameters, and \( \Delta K_p \), \( \Delta K_i \), and \( \Delta K_d \) are the corrections from the fuzzy inference system. Defuzzification is performed using the centroid method to convert fuzzy outputs into crisp values for real-time control.

To optimize the fuzzy PID controller, we employ a genetic algorithm. The GA enhances the performance by fine-tuning the initial parameters, quantization factors, and scaling factors of the fuzzy controller. The optimization process begins with defining a fitness function based on the integral of time multiplied by absolute error (ITAE), which serves as a performance index:

$$ J = \int_0^\infty t |E(t)| dt $$

Since a lower ITAE indicates better performance, the fitness function is set as:

$$ F = \frac{1}{J} $$

This ensures that the GA seeks to minimize the ITAE, thereby improving the response characteristics of the end effector control system.

The GA uses real-number encoding for parameters such as the quantization factors \( K_e \) and \( K_{ec} \), and the PID gains \( K_p \), \( K_i \), and \( K_d \). Each individual in the population is represented as a sequence \(\{a_1, a_2, \dots, a_{10}\}\), where each element is a random value between 0 and 9. Decoding is performed to map this sequence to actual parameter values within specified ranges. For example, for a parameter with range \([m, n]\), the decoded value is calculated as:

$$ \text{result} = \frac{g \cdot d \cdot (n – m)}{10 \cdot (d(1) – 1)} + m $$

where \( d \) is the sequence \(\{10^9, 10^8, 10^7, \dots, 10^0\}\). This encoding scheme allows for efficient exploration of the parameter space.

Selection in the GA is based on the roulette wheel method, where the probability of selecting an individual is proportional to its fitness. For a population of size \( n \), the probability \( p_i \) for individual \( i \) with fitness \( f_i \) is:

$$ p_i = \frac{f_i}{\sum_{i=1}^n f_i} $$

This promotes the survival of individuals with higher fitness, aligning with the goal of optimizing the end effector control.

Crossover and mutation probabilities are adaptive to maintain diversity and avoid premature convergence. The crossover probability \( p_c \) and mutation probability \( p_m \) are defined as:

$$ p_c = \begin{cases}

k_1 \left( \frac{f_{\text{max}} – f_m}{f_{\text{max}} – f_{\text{avg}}} \right) & \text{if } f_m \geq f_{\text{avg}} \\

k_2 & \text{if } f_m < f_{\text{avg}}

\end{cases} $$

$$ p_m = \begin{cases}

k_3 \left( \frac{f_{\text{max}} – f}{f_{\text{max}} – f_{\text{avg}}} \right) & \text{if } f \geq f_{\text{avg}} \\

k_4 & \text{if } f < f_{\text{avg}}

\end{cases} $$

Here, \( f_{\text{max}} \) is the maximum fitness in the population, \( f_{\text{avg}} \) is the average fitness, \( f_m \) is the higher fitness of the two individuals undergoing crossover, and \( f \) is the fitness of the individual to be mutated. Constants \( k_1, k_2, k_3, k_4 \) are set between 0 and 1. This adaptive approach ensures that individuals with fitness close to the maximum have lower probabilities of alteration, preserving good solutions, while those with lower fitness are more likely to be modified to explore new areas.

The termination condition for the GA is set to a maximum of 100 generations. Throughout the optimization, the GA iteratively evaluates the fuzzy PID model, with the output used to compute fitness values. The evolution of fitness over generations shows convergence, indicating that the GA effectively improves the controller parameters for the end effector. After optimization, the best parameters obtained are \( K_p = 10.2314 \), \( K_i = 3.6561 \), and \( K_d = 1.5574 \), starting from initial values of \( K_p = 15 \), \( K_i = 2 \), and \( K_d = 0.2 \).

To validate the proposed control strategy, we conduct simulations using MATLAB/Simulink. A model of the end effector grasping system is constructed, incorporating the dynamics and control algorithms. We compare three control methods: traditional PID, fuzzy PID, and GA-optimized fuzzy PID (GA-Fuzzy-PID). The simulation inputs a step signal of 20 N, representing the target grasping force for fruits like apples. The performance metrics analyzed include overshoot, settling time, peak time, rise time, and steady-state error.

The simulation results demonstrate that the GA-Fuzzy-PID controller outperforms the others in terms of response speed and stability. For instance, the GA-Fuzzy-PID achieves a settling time of 0.419 seconds, significantly faster than traditional PID (0.833 seconds) and fuzzy PID (0.742 seconds). The overshoot is reduced to 0.60%, compared to 8.09% for PID and 10.65% for fuzzy PID. Additionally, the steady-state error is minimized to 0.08 N, indicating high precision in force control. These improvements are crucial for the end effector to handle fruits without causing damage.

We also test the controllers under random disturbances to assess robustness. The GA-Fuzzy-PID controller shows rapid recovery and maintains stable tracking of the target force, highlighting its superior anti-interference capability. This is essential for real-world harvesting environments where external factors like vibrations or fruit variability may affect the end effector performance.

Following simulations, we perform physical experiments using a custom-built harvesting robot system. The setup includes a UR5e robotic arm, an Advantech EPC-P3000 industrial computer, a RealSense D455 camera for vision, and a Wheeltec bionic flexible gripper as the end effector. The experiments involve 50 apple-picking trials for each control algorithm, with success defined as undamaged fruit after grasping. The results are summarized in the table below:

| Control Algorithm | Successful Picks | Average Time per Fruit (s) | Damaged Fruits | Success Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PID | 41 | 6.13 | 9 | 82 |

| Fuzzy PID | 42 | 5.86 | 8 | 84 |

| GA-Fuzzy-PID | 45 | 5.01 | 5 | 90 |

The GA-Fuzzy-PID controller achieves a success rate of 90%, with an average picking time of 5.01 seconds per fruit and only 5 damaged apples. This outperforms both traditional PID and fuzzy PID, confirming the effectiveness of the genetic algorithm optimization in enhancing the end effector’s real-world performance.

During the experiments, we monitor the grasping force and voltage signals from the tactile sensors. The data shows that the GA-Fuzzy-PID controller maintains a stable grasping force around 20 N, with minimal fluctuations in voltage signals. This consistency ensures reliable grasping across fruits of varying sizes, further validating the robustness of the proposed control strategy for the harvesting end effector.

In conclusion, this study presents a GA-optimized fuzzy PID control method for improving the performance of harvesting end effectors. By integrating fuzzy logic with genetic algorithm optimization, we address key challenges such as parameter tuning inefficiencies and nonlinear dynamics. The simulation and experimental results demonstrate that the GA-Fuzzy-PID controller offers faster response, lower overshoot, reduced steady-state error, and better disturbance rejection compared to conventional methods. These advancements contribute to more efficient and damage-free fruit harvesting, supporting the broader adoption of agricultural robots. Future work could explore real-time adaptation of the control parameters or extend the approach to other types of end effectors for diverse cropping systems.

The development of intelligent control systems for end effectors is pivotal for advancing agricultural automation. As the demand for precision farming grows, optimizing the end effector’s grasping capabilities through algorithms like GA-Fuzzy-PID will play a crucial role in enhancing productivity and sustainability. This research underscores the importance of interdisciplinary approaches, combining control theory, optimization techniques, and robotic design to address practical challenges in modern agriculture.

Throughout this work, the term “end effector” has been emphasized to highlight its centrality in harvesting robots. The end effector is not merely a mechanical component but a sophisticated system that requires precise control to interact delicately with biological materials. By leveraging advanced control strategies, we can unlock the full potential of robotic end effectors, paving the way for smarter and more resilient agricultural practices.

In summary, the genetic algorithm optimization of fuzzy PID control provides a robust framework for enhancing end effector performance. The methodology detailed here—from kinetic modeling to experimental validation—offers a comprehensive approach that can be adapted to various robotic applications. As technology evolves, continued refinement of such control systems will be essential for meeting the growing food production demands while minimizing environmental impact.