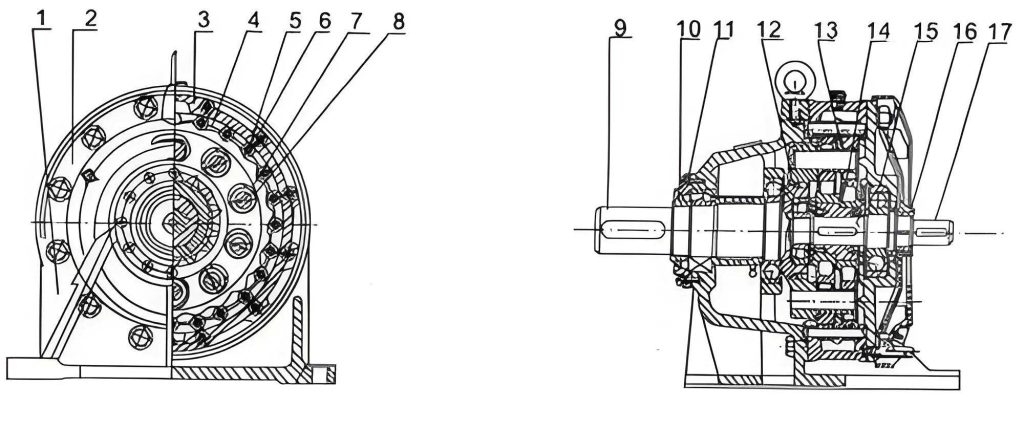

As a maintenance engineer responsible for heavy construction equipment, I encountered a critical failure in one of our tower cranes, specifically within its cycloidal drive system. The crane, a model that had served reliably for nearly a decade, suddenly lost its slewing capability during a crucial lifting operation. This immediate loss of function halted the entire construction project, underscoring the vital role the cycloidal drive plays in the smooth and controlled rotation of the tower crane’s upper structure. The following is a detailed, first-person narrative of the diagnostic process, technical analysis, and the comprehensive repair strategy we developed and executed to restore the cycloidal drive to full operational status.

Upon disassembling the speed reducer unit, the root cause became starkly visible: the secondary-stage cycloidal drive disc, a core component in the torque transmission mechanism, exhibited severe damage. Multiple cracks, significant wear patterns, and sections where material had spalled off were present on the disc’s surface. The failure was extensive, threatening the structural integrity of the entire reduction stage. With no replacement part readily available in the market, and considering the high cost and long lead time for a new cycloidal drive component, we made the decision to attempt a repair through welding. This was not a trivial undertaking, given the material’s notorious reputation for poor weldability.

The damaged component was manufactured from GCr15 bearing steel, a high-carbon chromium alloy. This material choice is excellent for wear resistance and hardness in a cycloidal drive application but presents formidable challenges for welding. To systematically address the repair, we first conducted a thorough weldability analysis. The high carbon content (typically around 1.0%) and chromium alloying lead to a high hardenability. This means that during the rapid heating and cooling cycle of welding, the heat-affected zone (HAZ) is prone to forming hard, brittle martensitic microstructures. The risk of cold cracking, driven by hydrogen embrittlement and residual stresses, is significantly elevated. Furthermore, the material’s sensitivity to hot cracking due to sulfur and phosphorus segregation had to be considered. The fundamental metallurgical challenge can be summarized by considering the carbon equivalent (Ceq), a predictive formula for hardenability. For GCr15-type steels, an applicable formula is:

$$ C_{eq} = C + \frac{Mn}{6} + \frac{Cr + Mo + V}{5} + \frac{Ni + Cu}{15} $$

Using typical composition ranges for GCr15, the calculated Ceq often exceeds 1.0, which falls into the “poor” or “very poor” weldability category. This quantitative analysis confirmed our qualitative assessment that special, stringent measures would be required for any welding repair on this cycloidal drive disc.

| Element | Content (wt.%) | Effect on Weldability |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | 0.95-1.05 | Primary cause of high hardness and cracking risk. |

| Chromium (Cr) | 1.30-1.65 | Increases hardenability and corrosion/wear resistance. |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.20-0.40 | Moderate effect on hardenability. |

| Silicon (Si) | 0.15-0.35 | Deoxidizer, can increase strength. |

| Sulfur (S) | ≤ 0.025 | Promotes hot cracking if segregated. |

| Phosphorus (P) | ≤ 0.027 | Promotes hot cracking and cold brittleness. |

| Calculated Ceq | ~1.10 – 1.25 | Indicates very poor weldability. |

The first practical step was the complete elimination of all cracks. Using a pneumatic grinder, we carefully removed all defective material. The grinding sequence was strategic: starting from the crack tips to prevent their propagation during the grinding process and moving towards the main body of the crack. For non-through-thickness cracks, we prepared a U-shaped groove with a smooth, radiused bottom to minimize stress concentration at the groove root. For through-thickness cracks, a single-V groove preparation was employed. The geometry of these grooves is critical for ensuring full penetration and managing distortion. The included angle for the V-groove was maintained at approximately 60-70 degrees. After grinding, the component was thoroughly cleaned with solvents to remove all grease, oil, and grinding debris, which are potential sources of hydrogen and welding defects.

With the defect preparation complete, we designed a multi-stage welding procedure. The core philosophy was to minimize heat input, control cooling rates, and use a filler metal with superior crack resistance. For the cycloidal drive disc, which requires high surface hardness and wear resistance post-repair, we selected an austenitic stainless steel electrode, specifically AWS E309-16 (equivalent to A307 mentioned in some contexts). Austenitic stainless steel deposits have high toughness and ductility, which help absorb stresses and resist cracking, even when deposited on a hardenable steel substrate. Although its machinability is not ideal, it was acceptable for the final precision grinding required. The electrodes were baked at 350°C for two hours to remove moisture and minimize the introduction of hydrogen.

The welding was performed using a DC power source set to reverse polarity (electrode positive). We meticulously controlled the welding parameters to keep the heat input low. Heat input (Q) per unit length is a key parameter calculated as:

$$ Q = \frac{\eta \cdot V \cdot I}{v} $$

where:

\( \eta \) = Arc efficiency (≈0.8 for SMAW),

\( V \) = Arc voltage (Volts),

\( I \) = Welding current (Amperes),

\( v \) = Travel speed (mm/s).

We aimed for a heat input range of 8-12 kJ/cm. This was achieved by using a low current, a relatively fast travel speed, and short weld beads. The welding sequence was critical to manage residual stresses. We began by welding the shortest, shallowest cracks first. The technique involved starting the arc at the crack tail and using a “stitch” or “tack” welding method, depositing small, isolated weld beads at intervals, allowing each to cool slightly before proceeding. This peening effect between beads helps to relieve some stress. After successfully completing the minor cracks without observing any new crack formation, we proceeded to the major through-thickness cracks. For these, after welding one side, the root was back-gouged completely using a grinder until sound base metal was revealed, before welding the opposite side. Finally, the areas of material loss and spalling were built up using a careful layer-by-layer deposition technique.

| Parameter | Value/Range | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Welding Process | Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW) | Versatility, good control in positional welding. |

| Filler Metal | AWS E309-16, Ø 3.25 mm | Austenitic structure resists cracking; provides a buffer layer. | Preheat | 150-200°C | Slows cooling rate, reduces risk of martensite formation and hydrogen cracking. |

| Interpass Temperature | ≤ 200°C | Prevents excessive heat buildup. |

| Welding Current | 90 – 105 A (DCEN) | Low current minimizes heat input and dilution. |

| Arc Voltage | 20 – 22 V | Stable arc condition. |

| Travel Speed | ~2.0 – 3.0 mm/s | Calculated to achieve target heat input. |

| Heat Input (Q) | 8 – 12 kJ/cm | Balances penetration needs with microstructural control. |

| Post-Weld Heat Treatment | None (Controlled slow cool in insulating material) | Avoids tempering of the base metal HAZ which could soften critical wear surfaces. |

Following the completion of all welding, the entire cycloidal drive disc was immediately wrapped in insulating ceramic blanket to facilitate a very slow, controlled cooling to room temperature. This step is crucial to prevent the formation of quenching cracks. Once at ambient temperature, the component underwent post-weld machining. The primary objective was to restore the original geometric dimensions and surface profile critical for the proper meshing action within the cycloidal drive. The two main faces were machined flat and parallel on a lathe. The intricate cycloidal profile around the periphery, which had been built up by welding, was then carefully ground and finished using precision grinding tools and hand filing, constantly checking against a master template. The final step involved a thorough non-destructive examination, primarily magnetic particle inspection (MPI), to verify the absence of any new cracks in the weld metal and heat-affected zones.

The success of this repair hinges on a deep understanding of the cycloidal drive principle. This type of reducer operates on the principle of eccentric motion. An input shaft with an eccentric bearing causes a cycloidal drive disc to undergo a compound wobbling motion. This motion, in turn, drives the output through a set of pins and rollers. The mathematical profile of the disc’s lobes is a cycloid or epicycloid curve. The reduction ratio (R) for a single-stage cycloidal drive is given by:

$$ R = \frac{N_p}{N_p – N_l} $$

where \( N_p \) is the number of pins (or rollers) in the stationary ring, and \( N_l \) is the number of lobes on the cycloidal drive disc. Typically, \( N_l = N_p – 1 \), leading to high reduction ratios in a compact space. The contact stresses between the disc lobes and the pins are exceptionally high, governed by Hertzian contact stress theory. The maximum contact pressure \( p_0 \) for two cylindrical surfaces can be approximated by:

$$ p_0 = \sqrt{\frac{F}{\pi L} \cdot \frac{\frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2}}{\frac{1-\nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1-\nu_2^2}{E_2}}} $$

where \( F \) is the normal force, \( L \) the contact length, \( R \) the radii of curvature, \( E \) the elastic modulus, and \( \nu \) Poisson’s ratio. This explains why the GCr15 material, with its high hardness and compressive strength, is chosen, and why any repair must restore comparable surface properties to withstand these repeated high-contact stresses.

| Property | GCr15 Base Metal (Hardened) | E309 Stainless Weld Metal | Implication for Repair |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness (HRC) | 58 – 65 | ~20 – 25 | Wear resistance must come from base metal; weld acts as structural filler. |

| Yield Strength (MPa) | > 1500 | ~450 | Weld zone is the “soft” link; design must avoid high tensile stresses here. |

| Elongation (%) | < 5 | > 30 | High ductility of weld metal helps accommodate strains and resist cracking. |

| Crack Resistance | Low (Brittle) | Very High | Primary reason for filler metal selection. |

The repaired cycloidal drive assembly was reinstalled in the tower crane’s slewing mechanism. After rigorous testing under no-load and progressively increasing load conditions, the performance was validated. The slewing motion was smooth, with no unusual noise or vibration, indicating proper meshing of the repaired disc. The crane was returned to service. This repair has now been in continuous operation for over five years in demanding construction environments, performing flawlessly. This outcome not only saved substantial replacement costs and project downtime but also provided invaluable insights into the limits and methodologies for repairing high-performance, hard-to-weld components like those found in precision cycloidal drive systems.

Reflecting on this experience, the repair of a cycloidal drive component is a multidisciplinary challenge intersecting metallurgy, mechanical design, and precision craftsmanship. It underscores the importance of a systematic approach: rigorous analysis of the base material’s weldability, meticulous preparation, selection of a metallurgically compatible filler metal, stringent control of welding thermal cycles, and precision post-weld machining. While the weld metal itself does not replicate the extreme surface hardness of the original cycloidal drive disc, its role is to restore structural integrity and geometric form. The critical wear surfaces remain the original, hardened GCr15 material exposed after final machining. This case study demonstrates that with careful procedure development and execution, even components with “very poor” weldability ratings can be successfully repaired, extending service life and contributing to sustainable equipment management practices. The cycloidal drive, with its compactness and high torque capability, remains a cornerstone of many motion control systems, and understanding its maintenance and repair is essential for engineers in the heavy machinery sector.

Furthermore, considering the operational lifespan of such drives, preventive maintenance strategies should include regular oil analysis to monitor wear debris and periodic inspections of the reduction gearbox. The loading conditions on a tower crane’s cycloidal drive are dynamic and complex, involving shock loads during slewing start/stop and variable moment loads from the jib. A simplified model for the torsional stress (\(\tau\)) on the cycloidal drive disc shaft can be related to the slewing torque (\(T\)) and the polar moment of inertia (\(J\)) of the rotating mass:

$$ \tau = \frac{T \cdot r}{J} $$

where \( r \) is the radius to the point of interest. Fatigue analysis, using modified Goodman or Gerber criteria, would be necessary for a full life assessment but was beyond the immediate scope of this emergency repair. However, our successful long-term outcome suggests that the stress state in the repaired regions was managed adequately. In conclusion, the knowledge gained from this repair of the tower crane’s cycloidal drive has been integrated into our standard maintenance protocols, ensuring that we are better prepared for future challenges with these critical and complex power transmission components.