The evolution of technology and shifting societal patterns have given rise to a growing need for intelligent companions for children, particularly within the preschool demographic. This paper focuses on the exploration and application of a user-centered emotional design methodology for companion robots, aiming to bridge the gap between the functional capabilities of such devices and the nuanced, perceptual needs of young children. Traditional design approaches often prioritize technological features or adult perceptions of utility, potentially overlooking the fundamental emotional and aesthetic preferences of the child user. This research posits that by systematically quantifying and integrating children’s latent perceptual demands into the design process, a more engaging, effective, and affectively resonant companion robot can be developed. The methodology employed here synthesizes Donald A. Norman’s three-level theory of emotional design with the quantitative analytical framework of Kansei Engineering. Through this integrated approach, vague perceptual impressions are translated into concrete design elements, guiding the creation of a companion robot that is not only functional but also emotionally supportive and developmentally appropriate for preschool-aged users.

Introduction and Problem Statement

The demographic landscape presents a significant market and social need for solutions supporting early childhood development and care. Following policy changes encouraging family growth, the population of preschool-aged children (3-6 years old) remains substantial. In contemporary dual-income households, parents often face time constraints, creating a demand for supplemental care and educational support. Concurrently, children are increasingly immersed in a digital environment from a young age. A well-designed companion robot has the potential to serve as a constructive bridge within this environment—facilitating learning, enabling communication with parents, and providing a sense of interactive companionship. However, a review of the current market reveals notable shortcomings. Many existing companion robots suffer from aesthetic homogenization, often featuring either overtly mechanical, “high-tech” appearances or overly simplistic, toy-like forms. There is frequently a disconnect between the consumer (the parent) and the primary user (the child), leading to products that may fulfill functional checklists but fail to engage children on an emotional or perceptual level. This gap highlights a critical research question: How can we systematically identify and integrate the genuine perceptual needs and emotional preferences of preschool children into the industrial design of a companion robot? This study addresses this question by employing a structured, data-driven methodology to extract, quantify, and apply key perceptual descriptors to the robot’s form, ultimately aiming to enhance user acceptance and emotional connection.

Theoretical Framework and Literature Synthesis

The theoretical foundation of this research rests on two pillars: Emotional Design and Kansei Engineering (KE). Emotional Design, as articulated by Donald Norman, categorizes user experience into three levels: Visceral, Behavioral, and Reflective. The Visceral level concerns the immediate impact of a product’s appearance, feel, and sound—the initial “gut reaction.” For a child’s companion robot, this translates to aesthetics that are perceived as friendly, warm, and inviting rather than cold or intimidating. The Behavioral level deals with the pleasure and effectiveness of use. The robot must be intuitive, functional, and reliable in its interactions. The Reflective level encompasses the personal meaning, cultural context, and long-term relationship a user forms with the product. A successful companion robot should foster a sense of attachment, trust, and become a meaningful part of the child’s daily life.

Kansei Engineering provides the methodological toolkit to operationalize these emotional goals. KE is a well-established field that translates human psychological feelings (Kansei) into concrete product design parameters. Previous studies have effectively used KE in various domains, such as analyzing user preferences for vehicle interiors or household appliances. The process typically involves: 1) collecting and screening perceptual (Kansei) words, 2) selecting representative product samples, 3) conducting user surveys using semantic differential scales, and 4) applying statistical analyses (like factor analysis, cluster analysis, and multiple regression) to establish quantitative relationships between perceptual evaluations and physical design elements. While prior research has applied similar methods to products for the elderly or general consumer goods, its focused application to the specific demographic of preschool children for companion robot design remains an area for deeper exploration. This study integrates Norman’s three-level model as a qualitative framework for understanding holistic needs, while employing KE’s quantitative rigor to pinpoint the specific design attributes that fulfill those needs, particularly at the crucial Visceral level.

Methodology: From Perceptual Words to Design Elements

The research process followed a structured, multi-stage pipeline designed to objectively capture children’s perceptions and link them to design variables.

Stage 1: Perceptual Vocabulary Collection and Screening. An initial pool of over 200 Chinese adjectives describing products or experiences was gathered from children’s literature, online product reviews, and design publications. Through synonym reduction and relevance filtering, this list was condensed to 105 words. A panel of 30 design professionals was then asked to select the most appropriate adjectives for describing an ideal companion robot for children. Adjectives selected by at least one-third of the panel (10 times) were shortlisted, resulting in 28 key perceptual words (e.g., “round,” “warm,” “cute,” “technological,” “simple,” “cold”).

Stage 2: Vocabulary Clustering via Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) and Cluster Analysis. To organize these 28 words into coherent perceptual dimensions, 30 respondents were asked to group words they considered similar in meaning. The co-occurrence frequency for each word pair was calculated to form a 28×28 similarity matrix. This matrix was first analyzed using Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) in SPSS to check the fitness of the data for spatial representation. The stress value obtained was $$Stress = 0.03422$$, which indicates a good fit (values close to 0 are optimal). Subsequently, hierarchical cluster analysis was performed on the same matrix. The dendrogram generated suggested a clear grouping structure. A cut-off point on the dendrogram yielded four primary clusters of perceptual words, which were interpreted as core perceptual dimensions for evaluation. Representative adjectives were chosen from each cluster to form the final semantic differential pairs for evaluation:

- Cluster 1 (Organic/Aesthetic): Rounded vs. Geometric

- Cluster 2 (Affective/Thermal): Warm vs. Cold

- Cluster 3 (Utilitarian/Stylish): Practical vs. Fashionable

- Cluster 4 (Formal/Complex): Simple vs. Complex

Stage 3: Sample Selection and Morphological Analysis. To avoid bias from existing, often homogenous, companion robot designs, nine stylistically diverse visual samples were selected from animations and films featuring characters or objects that could be analogous to a robot. These samples provided a broad spectrum of visual styles. Each sample was then decomposed into five morphological categories with specific class items:

| Category | Class Items (and codes) |

|---|---|

| Contour (A) | Rounded (A1), Balanced (A2), Angular (A3) |

| Color Tone (B) | Warm (B1), Neutral (B2), Cool (B3) |

| Size (C) | Large (>60cm, C1), Medium (30-60cm, C2), Small (<30cm, C3) |

| Material Texture (D) | Smooth (D1), Rough (D2), Furry (D3) |

| Character Type (E) | Humanoid (E1), Animal-like (E2), Mechanical (E3) |

This created a binary matrix (Table X) where each sample was coded ‘1’ for the applicable class item in each category and ‘0’ for others.

Stage 4: User Evaluation and Data Collection. A 5-point semantic differential scale questionnaire was constructed using the four adjective pairs. Given the target users are preschoolers (3-6 years old), the survey was administered to 80 parent-child pairs in a major city. Parents guided their children in evaluating the nine samples against the four adjective pairs. A total of 69 valid responses were collected. The mean score for each sample on each adjective pair was calculated, resulting in a matrix of perceptual evaluation data.

Stage 5: Quantitative Analysis – Multiple Regression Analysis. To establish the quantitative relationship between the morphological elements (independent variables) and the perceptual scores (dependent variables), Quantification Theory Type I (a multiple regression analysis for categorical variables) was employed. The binary morphological matrix for the nine samples served as the input for the independent variables. The four sets of mean perceptual scores served as the dependent variables in four separate regression analyses. The analysis yields two key outputs for each perceptual dimension: 1) The coefficient (partial regression weight) for each class item (e.g., A1, B2, C3), indicating its contribution to that perceptual score, and 2) The coefficient of determination ($R^2$), indicating how well the morphological variables explain the variance in the perceptual scores. The formula for the predicted perceptual score $\hat{Y}_k$ for dimension $k$ is:

$$

\hat{Y}_k = \sum_{i=1}^{m} \sum_{j=1}^{l_i} \beta_{kij} \delta_{ij} + \bar{Y}_k

$$

where $\beta_{kij}$ is the regression coefficient for class $j$ in category $i$ for perceptual dimension $k$, $\delta_{ij}$ is a dummy variable (1 if the sample has that class, 0 otherwise), $m$ is the number of morphological categories, $l_i$ is the number of classes in category $i$, and $\bar{Y}_k$ is the mean score for dimension $k$. The $R^2$ value is calculated as:

$$

R^2 = 1 – \frac{SS_{res}}{SS_{tot}}

$$

where $SS_{res}$ is the sum of squares of residuals and $SS_{tot}$ is the total sum of squares.

Data Analysis and Results

The statistical analysis provided clear, actionable insights into which design elements drive specific perceptual impressions in the context of a companion robot for children. The results of the multiple regression analysis for the four perceptual dimensions are summarized in the table below. The coefficients show the strength and direction of influence for each design class item.

| Category / Class Item | Rounded-Geometric Coeff. | Warm-Cold Coeff. | Practical-Fashionable Coeff. | Simple-Complex Coeff. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contour (A) | ||||

| Rounded (A1) | 0.676 | 0.586 | 0.007 | -0.750 |

| Balanced (A2) | 0.078 | 0.065 | -0.563 | 0.304 |

| Angular (A3) | -0.896 | -0.775 | 0.629 | 0.552 |

| Color Tone (B) | ||||

| Warm (B1) | -0.010 | 0.128 | -0.132 | 0.145 |

| Neutral (B2) | -0.061 | 0.035 | 0.161 | -0.155 |

| Cool (B3) | 0.081 | -0.193 | -0.025 | 0.003 |

| Size (C) | ||||

| Large (C1) | 0.370 | 0.322 | -0.449 | -0.021 |

| Medium (C2) | 0.468 | 0.634 | 0.048 | -0.668 |

| Small (C3) | -0.702 | -0.838 | 0.236 | 0.682 |

| Material (D) | ||||

| Smooth (D1) | 0.223 | 0.063 | -0.563 | -0.211 |

| Rough (D2) | 0.137 | 0.092 | 0.604 | 0.033 |

| Furry (D3) | -0.417 | -0.181 | -0.084 | 0.199 |

| Type (E) | ||||

| Humanoid (E1) | 0.606 | 0.496 | -0.497 | -0.503 |

| Animal-like (E2) | -0.606 | -0.496 | 0.503 | |

| Mechanical (E3) | 0.530 | 0.425 | 0.235 | |

| Model R² | 0.915 | 0.835 | 0.563 | 0.627 |

Interpretation of Key Findings:

- For a “Rounded” and “Warm” Impression: High positive coefficients for Rounded Contour (A1), Medium Size (C2), and Humanoid/Mechanical Type (E1/E3) strongly contribute to these perceptions. Interestingly, Animal-like (E2) form showed a negative correlation, suggesting the selected samples in this category may have been perceived as too simplistic or toy-like, not conveying the desired warmth associated with a sophisticated companion. Cool Colors (B3) negatively impacted the “Warm” score.

- For a “Simple” Impression: Rounded Contour (A1) and Medium Size (C2) again showed strong contributions (negative coefficient for A1 indicates it promotes “Simple” over “Complex”). Small Size (C3) and Animal-like form (E2) were associated with greater “Complexity.”

- For a “Fashionable” over “Practical” Impression: Angular Contour (A3), Rough Texture (D2), and Animal-like form (E2) were key drivers. Smooth Texture (D1) and Humanoid form (E1) were strongly associated with “Practical.”

- Model Fit: The high $R^2$ values for “Rounded-Geometric” (0.915) and “Warm-Cold” (0.835) indicate the morphological elements excellently explain perceptions on these dimensions. The moderate $R^2$ for the other two dimensions suggests other factors may also be involved, but the models are still informative.

In summary, the data prescribes a companion robot with a dominantly rounded contour, in a medium size (approx. 30-60cm), potentially blending humanoid or refined mechanical cues rather than a literal animal mimicry, and finished in a smooth material to achieve a balance of warm, friendly, simple, yet technologically credible aesthetics.

Design Application and Prototype Development

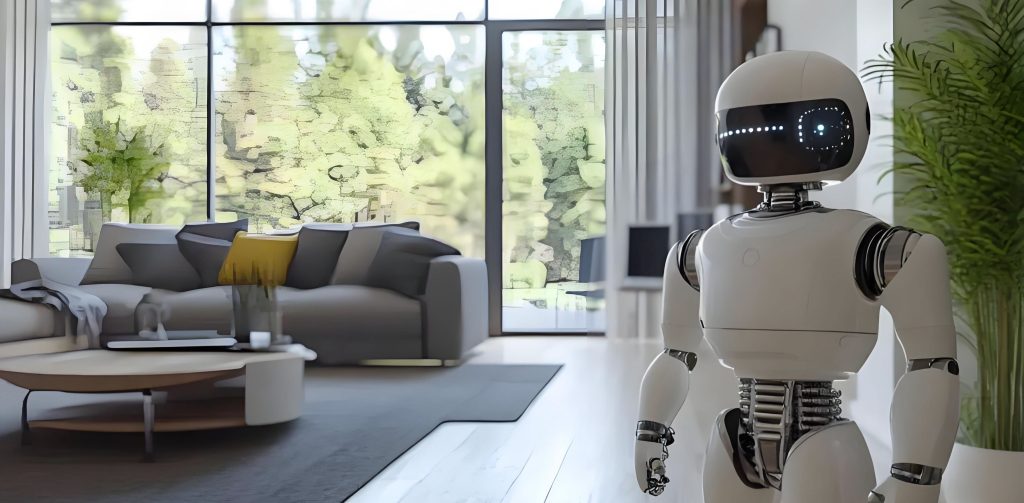

Guided by the quantitative analysis and framed within the three-level theory of emotional design, a new companion robot concept was developed for preschoolers.

Visceral Level (Appearance): The form adopts a cohesive, rounded silhouette with flowing curves to maximize the “rounded” and “warm” coefficients. The primary form language avoids sharp angles and complex geometries. A neutral color palette dominated by white and light gray is used, accented with a darker gray for interactive elements. This balances approachability with a sense of calm sophistication, avoiding overly childish or cold, sterile tech aesthetics. The size is set within the “medium” range, making it substantial enough to be perceived as a presence but not intimidating or overly bulky for a child’s space.

Behavioral Level (Interaction & Function): The robot’s functions are designed to be intuitive and support developmental needs. It features a central display for visual feedback, video calls, and educational content. Simple, tangible buttons provide clear affordances for core functions: voice interaction, music playback, video calling, and projection. A key behavioral feature is an emotion-feedback system. The robot can display simple, abstract emotional states (joy, curiosity, sleepiness) on its screen based on interaction context—celebrating a completed task or suggesting a break after prolonged use. This fosters a sense of reciprocal interaction. Core functionalities include: secure video communication with parents, access to curated educational apps, interactive storytelling, and a safe, parent-managed environment for play.

Reflective Level (Meaning & Relationship): The design aims to encourage the robot to be perceived as a consistent, reliable companion rather than just a tool. The emotion-feedback system is crucial here, helping to build a rudimentary sense of empathy and relationship. By facilitating easy and fun communication with parents, the robot positions itself as a positive bridge within the family, strengthening its reflective value. Its non-threatening, friendly appearance allows it to be welcomed into personal spaces like a bedroom, encouraging a long-term bond.

The final design was modeled and rendered to create high-fidelity visualizations. To validate the design against the original perceptual goals, a follow-up survey using a 5-point Likert scale was conducted with 119 parent-child pairs. The new design scored highly on the target adjectives: “Rounded” (1.54), “Warm” (1.21), “Fashionable” (-0.87, indicating a strong shift towards “Fashionable” from “Practical”), and “Simple” (1.01). These results confirm that the data-driven design process successfully translated target perceptual qualities into a tangible companion robot design.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates the efficacy of integrating a structured, quantitative perceptual methodology with holistic emotional design theory for the development of children’s companion robots. By employing Kansei Engineering techniques—specifically cluster analysis and multiple regression analysis—the often-elusive emotional and aesthetic preferences of preschool children were successfully quantified and mapped onto specific morphological design elements. The resulting design guidelines emphasized rounded contours, medium scale, and a balanced, neutral aesthetic to evoke warmth, simplicity, and a friendly technological presence. The developed companion robot prototype, informed by these guidelines and the three levels of emotional design, scored highly in validation tests targeting the desired perceptual qualities. This study provides a replicable framework for designers and researchers in the field of child-robot interaction, shifting the focus from purely functional specification to a more nuanced, user-centered approach that prioritizes the child’s emotional experience. Future work could involve creating physical prototypes for longitudinal interaction studies, exploring auditory and tactile perceptual dimensions, and adapting the methodology for different age subgroups within childhood. Addressing the challenge of directly capturing reliable perceptual data from very young children also remains an important area for methodological refinement.