In the realm of precision mechanical transmissions, the planetary roller screw mechanism stands out as a highly efficient device for converting rotary motion into linear actuation. Its multi-stage variant, which couples multiple planetary roller screw assemblies, offers significant advantages such as large stroke-to-length ratios, high load capacity, and smooth operation without stage-switching impacts. These attributes make multi-stage planetary roller screw mechanisms indispensable in aerospace, automotive, and industrial automation applications where space constraints and performance demands are stringent. This article delves into the rigid-body dynamic modeling of such multi-stage systems, providing a comprehensive analysis based on Newton’s second law. I will explore the kinematic and force relationships between stages, derive the governing equations of motion, and present a solution methodology. Through numerical examples, the influence of interfacial friction coefficients on dynamic behavior will be examined, emphasizing the role of the planetary roller screw design in optimizing performance.

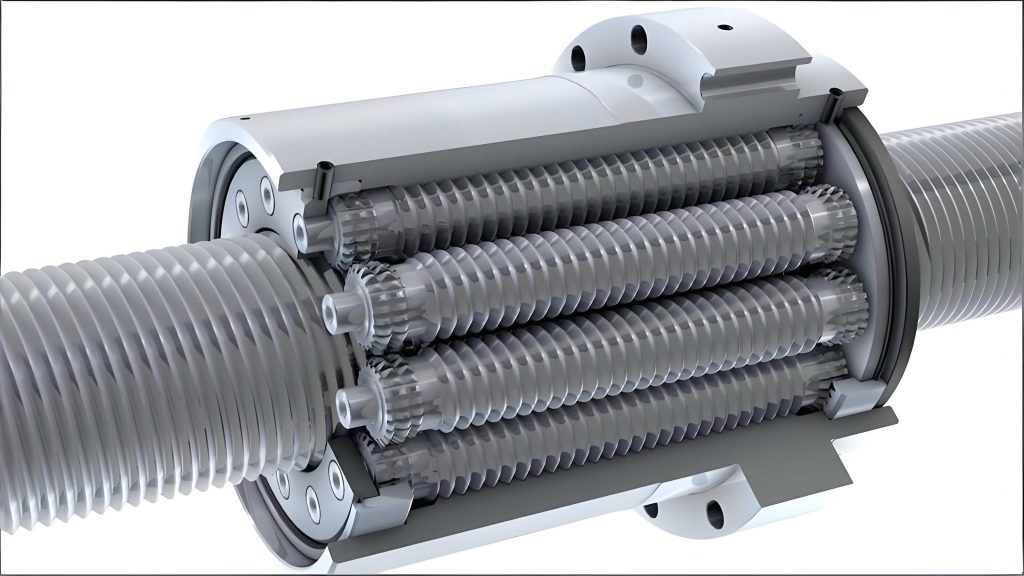

The fundamental operation of a planetary roller screw mechanism involves a screw, multiple rollers, a nut, and a retainer (or cage). In a multi-stage configuration, these components are stacked sequentially, with each stage’s nut connected to the next stage’s screw via thrust bearings to transmit axial loads. This arrangement allows for cumulative linear displacement while maintaining a compact form factor. Understanding the dynamics of a multi-stage planetary roller screw is crucial for predicting its response under various operational conditions, such as step inputs or fluctuating loads. Previous studies have primarily focused on single-stage planetary roller screw mechanisms, addressing aspects like contact kinematics, load distribution, and efficiency. However, the dynamics of multi-stage systems remain underexplored, particularly when considering the complex interactions between stages. My aim here is to fill this gap by developing a rigid-body dynamic model that accounts for the inertial effects and frictional forces inherent in multi-stage planetary roller screw mechanisms.

To begin, let us consider the structural composition of a multi-stage planetary roller screw. Assume there are \( n_{Ex} \) stages, indexed by \( k = 1, 2, \dots, n_{Ex} \). Each stage consists of a screw, rollers, a nut, and a cage. The screws are coupled via spline connections, and the nuts are constrained from rotating. The first-stage screw is driven, while subsequent screws rotate and translate axially due to the motion of preceding nuts. The coordinate system is defined with the Z-axis aligned along the screw axis, and the origin at the bearing support of the first-stage screw. The rotational speed of all screws is identical, given by:

$$ \dot{\theta}_{S1} = \dot{\theta}_{S2} = \dots = \dot{\theta}_{Sk} = \dot{\theta}_S $$

For stages \( k > 1 \), the axial velocity of the screw equals that of the previous nut:

$$ v_{Sk} = v_{N(k-1)} $$

The axial velocity of the nut in the \( k \)-th stage is derived from the screw rotation and the cumulative lead:

$$ v_{Nk} = -\frac{\dot{\theta}_S}{2\pi} \sum_{i=1}^{k} L_{Si} $$

where \( L_{Si} \) is the lead of the \( i \)-th screw. These kinematic relations form the basis for analyzing the forces and motions in a multi-stage planetary roller screw mechanism.

In a multi-stage planetary roller screw, the force transmission between stages involves interfacial friction at the screw-screw and nut-screw connections. For the \( k \)-th stage, the friction force at the screw spline and the friction torque at the nut connection are expressed as:

$$ f_{Sk} = -\mu_{SS} \frac{|M_{Sk}|}{r_{SSk}} \text{sign}(v_{Sk}) $$

$$ M_{Nk} = \mu_{NS} |F_{Nk}| r_{NSk} \text{sign}(\dot{\theta}_S) $$

Here, \( \mu_{SS} \) and \( \mu_{NS} \) are the friction coefficients, \( r_{SSk} \) and \( r_{NSk} \) are effective radii, and \( \text{sign}(\cdot) \) denotes the sign function. These frictional effects significantly influence the dynamic response, especially during transient operations of the planetary roller screw mechanism.

The heart of the dynamic analysis lies in deriving the equations of motion for each component. Using Newton’s second law, I formulate the equations for rollers, screws, nuts, and cages, neglecting manufacturing errors and elastic deformations. For the \( k \)-th roller, the forces include contact forces from the screw and nut, friction at the screw-roller interface, and forces from the cage and internal gear. The roller’s motion in the local coordinate system \( o_{Pk}-x_{Pk}y_{Pk}z_{Pk} \) (attached to the cage) is governed by:

$$ \mathbf{F}^P_{RSk} + \mathbf{f}^P_{RSk} + \mathbf{F}^P_{RNk} + 2\mathbf{F}^P_{RPk} + 2\mathbf{F}^P_{RGk} – m_{Rk} \begin{bmatrix} \dot{\theta}_{Pk}^2 (r_{Sk} + r_{Rk}) \\ \ddot{\theta}_{Pk} (r_{Sk} + r_{Rk}) \\ -\ddot{\theta}_S L_{Sk} / (2\pi) \end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{0} $$

where \( \mathbf{F}^P_{RSk} \) and \( \mathbf{F}^P_{RNk} \) are contact force vectors, \( \mathbf{f}^P_{RSk} \) is the friction force vector, \( \mathbf{F}^P_{RPk} \) and \( \mathbf{F}^P_{RGk} \) are forces from the cage and internal gear, \( m_{Rk} \) is the roller mass, and \( r_{Sk} \) and \( r_{Rk} \) are radii. The contact force vectors are derived from the surface normals at the engagement points. For instance, the screw-roller contact force is:

$$ \mathbf{F}^P_{RSk} = F_{RSk} \frac{\mathbf{n}^P_{RSk}}{\|\mathbf{n}^P_{RSk}\|} $$

with the normal vector \( \mathbf{n}^P_{RSk} \) given by:

$$ \mathbf{n}^P_{RSk} = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\phi_{RSk} \tan\beta_{RSk} – \sin\phi_{RSk} \tan\lambda_{RSk} \\ -\sin\phi_{RSk} \tan\beta_{RSk} – \cos\phi_{RSk} \tan\lambda_{RSk} \\ -1 \end{bmatrix} $$

Here, \( \phi_{RSk} \), \( \beta_{RSk} \), and \( \lambda_{RSk} \) are the engagement angle, flank angle, and helix angle at the contact point. The friction force follows the Coulomb model:

$$ \mathbf{f}^P_{RSk} = F_{RSk} \mu_{RS} \frac{\mathbf{v}^P_{RSk}}{\|\mathbf{v}^P_{RSk}\|}, \quad \dot{\theta}_S \neq 0 $$

where \( \mu_{RS} \) is the screw-roller friction coefficient and \( \mathbf{v}^P_{RSk} \) is the relative sliding velocity. The roller’s rotational dynamics are described by:

$$ r_{Rk} F_{RNyk} – r_{RSk} \cos\phi_{RSk} (F_{RSyk} + f_{RSyk}) – r_{RSk} \sin\phi_{RSk} (F_{RSxk} + f_{RSxk}) + 2 r_{RGk} F_{RGyk} – J_{Rk} \ddot{\theta}_{Rk} = 0 $$

with \( J_{Rk} \) as the roller’s moment of inertia and \( \ddot{\theta}_{Rk} \) its angular acceleration.

For the screw in the \( k \)-th stage, the axial and rotational equations are:

$$ -F_{N(k-1)} + f_{Sk} – f_{S(k+1)} + F_{SRzk} + f_{SRzk} – m_{Sk} \ddot{z}_{Sk} = 0 $$

$$ r_{SRk} \left[ \cos\phi_{SRk} (F_{SRyk} + f_{SRyk}) – \sin\phi_{SRk} (F_{SRxk} + f_{SRxk}) \right] – M_{N(k-1)} + M_{Sk} – M_{S(k+1)} – J_{Sk} \ddot{\theta}_{Sk} = 0 $$

where \( m_{Sk} \) and \( J_{Sk} \) are the screw’s mass and moment of inertia, \( F_{SRzk} \), \( f_{SRzk} \), etc., are components of the reaction forces from the roller, and \( M_{Sk} \) is the driving torque. For the first stage, \( f_{S1} = 0 \), and for the last stage, \( M_{S(n_{Ex}+1)} = 0 \).

The nut’s motion equations account for axial force balance and torque constraint:

$$ -n_{\text{roller}} F_{RNzk} + F_{Nk} + m_{Nk} \frac{\ddot{\theta}_S L_{Sk}}{2\pi} = 0 $$

$$ M_{Nk} + M_{Ck} – r_{Nk} F_{RNyk} – r_{NGk} F_{RGyk} = 0 $$

Here, \( n_{\text{roller}} \) is the number of rollers, \( m_{Nk} \) is the nut mass, \( M_{Ck} \) is the constraint torque preventing nut rotation, and \( r_{Nk} \) and \( r_{NGk} \) are the nut radius and internal gear pitch radius. The cage dynamics are simpler, as it primarily rotates due to roller interactions:

$$ -n_{\text{roller}} F_{RPyk} (r_{Sk} + r_{Rk}) – J_{Pk} \ddot{\theta}_{Pk} = 0 $$

with \( J_{Pk} \) as the cage’s moment of inertia.

To solve these equations for a multi-stage planetary roller screw mechanism, I propose a sequential approach. Starting from the last stage (\( k = n_{Ex} \)), the equations are solved given the input screw speed \( \dot{\theta}_S \) and the external load \( F_{N(n_{Ex})} \). The computed forces and torques, such as \( F_{N(k-1)} \) and \( M_{Sk} \), are then used as inputs for the preceding stage. This backward propagation continues until the first stage is reached. The solution yields the dynamic state of all components, including velocities, accelerations, and contact forces. This methodology enables the analysis of transient and steady-state behavior in multi-stage planetary roller screw systems.

To illustrate the application, consider a two-stage planetary roller screw mechanism. The parameters for each stage are summarized in Table 1. These parameters reflect typical designs used in high-precision applications, with the second-stage components being larger to handle increased loads.

| Parameter | Stage 1 | Stage 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Screw nominal radius, \( r_{Sk} \) (mm) | 9.75 | 16.50 |

| Roller nominal radius, \( r_{Rk} \) (mm) | 3.25 | 5.50 |

| Nut nominal radius, \( r_{Nk} \) (mm) | 16.25 | 27.50 |

| Number of screw threads, \( n_{Sk} \) | 5 | 5 |

| Lead, \( L_{Sk} \) (mm) | 10 | 10 |

| Flank angle, \( \beta_{Sk} \) (degrees) | 45 | 45 |

| Number of rollers, \( n_{\text{roller}} \) | 7 | 7 |

| Roller mass, \( m_{Rk} \) (kg) | 0.014 | 0.039 |

| Screw mass, \( m_{Sk} \) (kg) | 0.761 (approx.) | 0.761 |

| Nut mass, \( m_{Nk} \) (kg) | 2.2 | 20 |

| Screw moment of inertia, \( J_{Sk} \) (kg·mm²) | 51.94 | 172.3 |

| Roller moment of inertia, \( J_{Rk} \) (kg·mm²) | 0.077 | 0.471 |

| Cage moment of inertia, \( J_{Pk} \) (kg·mm²) | 2.95 | 19.88 |

| Screw-screw friction coefficient, \( \mu_{SS} \) | Varied (0.10, 0.15, 0.20) | |

| Nut-screw friction coefficient, \( \mu_{NS} \) | Varied (0.005, 0.055, 0.105) | |

| Screw-roller friction coefficient, \( \mu_{RS} \) | 0.05 | |

The dynamic model is first validated by reducing it to a single-stage planetary roller screw mechanism and comparing results with existing literature. For a step input of \( \dot{\theta}_S = 1 \, \text{rad/s} \) and a load \( F_{N1} = 100 \, \text{N} \), with a viscous friction model \( \mathbf{f}^P_{RSk} = \mu’_{RS} \mathbf{v}^P_{RSk} \) where \( \mu’_{RS} = 25 \, \text{N·s/m} \), the cage speed ratio \( \zeta_{PS1} = \dot{\theta}_{P1} / \dot{\theta}_S \) matches prior studies closely, confirming the model’s accuracy.

For the two-stage planetary roller screw, simulations are run with \( \dot{\theta}_S = 100 \, \text{rad/s} \), \( F_{N2} = 7000 \, \text{N} \), and varying friction coefficients. The efficiency \( \eta \) of the mechanism is calculated as:

$$ \eta = \frac{F_{N2} \cdot (L_{S1} + L_{S2})}{2\pi M_{S1}} $$

where \( M_{S1} \) is the driving torque on the first-stage screw. The cage speed ratio for each stage is \( \zeta_{PSk} = \dot{\theta}_{Pk} / \dot{\theta}_S \). Contact forces, such as those between the internal gear and roller \( F_{RGk} \) and between the cage and roller \( F_{RPk} \), are computed as:

$$ F_{RGk} = \frac{|F_{RGyk}|}{\cos\alpha_{RG}}, \quad F_{RPk} = \sqrt{F_{RPxk}^2 + F_{RPyk}^2} $$

with \( \alpha_{RG} = 20^\circ \) being the pressure angle.

When varying the screw-screw friction coefficient \( \mu_{SS} \) from 0.10 to 0.20, the results show that the steady-state cage speed ratio is slightly higher for the second stage due to smaller helix angles. The efficiency exhibits a two-step rise during transients, starting around 0.60 and stabilizing near 0.87. This behavior correlates with the cage accelerations: as each stage’s cage reaches steady speed, the tangential component of screw-roller friction decreases, reducing losses. The internal gear-roller contact force \( F_{RGk} \) initially drops to zero then recovers slightly, while the cage-roller force \( F_{RPk} \) increases rapidly to steady-state. Notably, forces in the first-stage planetary roller screw are larger than in the second stage, despite the first-stage screw having a smaller radius, due to higher interfacial loads. The influence of \( \mu_{SS} \) on efficiency is minimal because the screw helix angles are small (e.g., 9.27° for stage 1 and 5.51° for stage 2). The approximate efficiency considering only screw-screw friction is:

$$ \eta_{SS} \approx \frac{1}{1 + \frac{\mu_{SS} \tan\lambda_{S1} \tan\lambda_{S2}}{\tan\lambda_{S1} + \tan\lambda_{S2}}} $$

which confirms the weak dependence.

Varying the nut-screw friction coefficient \( \mu_{NS} \) from 0.005 to 0.105 has a more pronounced effect. Efficiency decreases significantly with higher \( \mu_{NS} \), as the friction torque \( M_{Nk} \) directly increases the required driving torque. However, other dynamic metrics like cage speeds and contact forces remain relatively unaffected. This underscores the importance of minimizing nut-screw friction in multi-stage planetary roller screw designs to enhance overall efficiency.

To further elucidate these trends, Table 2 summarizes key dynamic outputs for different friction scenarios. The data highlights how friction coefficients impact the performance of a multi-stage planetary roller screw mechanism.

| Friction Coefficient | Steady-State \( \zeta_{PS1} \) | Steady-State \( \zeta_{PS2} \) | Steady-State Efficiency \( \eta \) | Max \( F_{RG1} \) (N) | Max \( F_{RP1} \) (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| \( \mu_{SS} = 0.10, \mu_{NS} = 0.055 \) | 0.192 | 0.198 | 0.872 | 15.3 | 8.7 |

| \( \mu_{SS} = 0.15, \mu_{NS} = 0.055 \) | 0.192 | 0.198 | 0.870 | 15.4 | 8.8 |

| \( \mu_{SS} = 0.20, \mu_{NS} = 0.055 \) | 0.192 | 0.198 | 0.868 | 15.5 | 8.9 |

| \( \mu_{SS} = 0.10, \mu_{NS} = 0.005 \) | 0.192 | 0.198 | 0.885 | 15.2 | 8.6 |

| \( \mu_{SS} = 0.10, \mu_{NS} = 0.105 \) | 0.192 | 0.198 | 0.859 | 15.4 | 8.8 |

The transient dynamics of a multi-stage planetary roller screw mechanism reveal interesting characteristics. For instance, the efficiency curve’s step-like rise corresponds to the settling times of the cages. The first stage’s cage, with lower inertia, stabilizes faster, causing the first efficiency step. The second stage’s cage, with higher inertia, takes longer, leading to the second step. This inertial effect is crucial for applications requiring rapid response, as it may induce vibrations or delays. The contact forces also exhibit transient dips and peaks, which could affect wear and fatigue life in planetary roller screw components. Engineers must consider these dynamics when designing control systems or selecting materials for multi-stage planetary roller screw mechanisms.

Expanding the analysis to more than two stages, the dynamic model can be generalized. For an \( n_{Ex} \)-stage planetary roller screw, the equations of motion form a coupled system that can be solved iteratively. The general form for the screw axial dynamics in the \( k \)-th stage is:

$$ \sum \text{Axial Forces} – m_{Sk} \ddot{z}_{Sk} = 0 $$

and for rotation:

$$ \sum \text{Torques} – J_{Sk} \ddot{\theta}_{Sk} = 0 $$

Similar equations apply to other components. The solution strategy remains backward propagation, making it scalable for any number of stages. This scalability is vital for designing customized multi-stage planetary roller screw systems for specific stroke and load requirements.

In practical applications, the planetary roller screw mechanism often operates under variable loads and speeds. The dynamic model can be extended to include time-varying inputs, such as \( \dot{\theta}_S(t) \) or \( F_{Nk}(t) \), by integrating the equations numerically. For example, using a Runge-Kutta method, one can simulate the response to sinusoidal or ramp inputs. This capability allows for thorough performance evaluation of multi-stage planetary roller screw drives in realistic scenarios, like aerospace actuation where loads fluctuate during flight.

Another aspect worth exploring is the effect of lubrication on friction coefficients. In a planetary roller screw, lubrication reduces \( \mu_{RS} \), \( \mu_{SS} \), and \( \mu_{NS} \), thereby improving efficiency and reducing heat generation. The dynamic model can incorporate variable friction coefficients as functions of temperature or speed, adding complexity but increasing accuracy. For instance, the Stribeck curve could model screw-roller friction, transitioning from boundary to hydrodynamic regimes. Such refinements would enhance the predictive power of the model for multi-stage planetary roller screw mechanisms operating in harsh environments.

To aid designers, I propose a set of dimensionless parameters that characterize multi-stage planetary roller screw dynamics. These include inertia ratios, friction ratios, and geometric ratios. For example, the inertia ratio between stages might be defined as \( \Gamma_k = J_{Sk} / J_{S(k-1)} \), and the friction ratio as \( \Psi_k = \mu_{SS} r_{SSk} / (\mu_{RS} r_{Sk}) \). Analyzing dynamics in terms of these parameters could reveal optimal configurations for minimizing transient overshoot or maximizing efficiency. This approach aligns with modern design philosophies for planetary roller screw mechanisms, where modularity and performance tuning are key.

In conclusion, the rigid-body dynamic model presented here provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing multi-stage planetary roller screw mechanisms. By deriving equations of motion from Newton’s second law and proposing a sequential solution method, I have enabled the computation of forces, torques, and motions across all stages. The analysis of friction effects shows that nut-screw friction significantly impacts efficiency, while screw-screw friction has a negligible influence for small helix angles. Transient behaviors, such as step-like efficiency changes and force variations, underscore the importance of dynamics in design and control. Future work could incorporate elastic deformations, manufacturing errors, and advanced friction models to further refine the analysis. Ultimately, this work contributes to the advancement of planetary roller screw technology, facilitating the development of more efficient and reliable multi-stage actuators for high-performance applications.

The versatility of the planetary roller screw mechanism makes it a cornerstone in precision engineering. As demands for compact, high-load linear drives grow, multi-stage configurations will become increasingly prevalent. By understanding their dynamics through models like the one described, engineers can optimize these systems for a wide range of applications, from robotics to aerospace. The planetary roller screw, in its multi-stage form, represents a synergy of mechanical ingenuity and dynamic analysis, promising continued innovation in motion control systems.