In my years of immersion in robotics and advanced manufacturing, I have witnessed numerous technological shifts, but few as transformative as the advent of spherical gears. The recent global spotlight on humanoid robots at major international events underscores a critical truth: the core of robotic agility and capability lies in its joints. For decades, the field has been constrained by traditional, single-axis output reducers. My exploration into this domain reveals that the spherical gear is not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental reimagining of robotic articulation, promising to elevate humanoid robots to unprecedented levels of dexterity and efficiency. This article delves deep into the mechanics, advantages, and burgeoning landscape of spherical gear technology, emphasizing its pivotal role in the next generation of autonomous systems.

The limitations of conventional robot joint mechanisms are well-documented in engineering literature and practical applications. These systems primarily rely on reducers that permit rotation around a single axis. To achieve multi-directional movement, multiple units must be combined, leading to bulk, weight, and compounded inefficiencies. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and shortcomings of the predominant traditional reducer types, based on my analysis and industry consensus.

| Reducer Type | Key Advantages | Primary Disadvantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision Planetary Gear | Compact size, light weight, high single-stage efficiency, strong load capacity, good shock resistance, lower cost. | Limited single-stage reduction ratio, requires periodic maintenance, lower precision compared to others. | General industrial automation, robotic arms where cost is a concern. |

| Harmonic Drive | Compact design, high reduction ratio, high transmission accuracy, zero backlash. | Lower load capacity, limited service life under heavy loads, higher cost. | Precision robotics, aerospace actuators, surgical robots. |

| RV (Rotary Vector) Reducer | Wide transmission ratio range, high rigidity, excellent overload capacity, smooth operation. | Large volume, high manufacturing complexity and cost. | Heavy-duty industrial robots, machine tool rotary axes. |

| Enveloping Worm Gear | High torque density, simple manufacturing, low cost, low noise, long life. | Lower transmission efficiency, fixed 90° output orientation, requires additional mechanisms for other directions. | Conveyors, packaging machinery with specific angular output needs. |

This reliance on stacked single-degree-of-freedom (DoF) systems creates inherent bottlenecks. For a humanoid robot’s shoulder or hip joint, which naturally requires two rotational degrees of freedom (e.g., abduction/adduction and flexion/extension), engineers must integrate two separate reducer-motor assemblies. This solution increases the joint’s mass and moment of inertia, reduces overall power density, and complicates the control architecture. The search for a more elegant, biomimetic solution has long been a holy grail in robotics. This is precisely where the spherical gear enters the scene, offering a paradigm shift.

The core innovation of the spherical gear mechanism is its ability to provide two rotational degrees of freedom directly from a single, compact assembly. Imagine a gear with teeth arranged on a spherical surface. This design allows for concurrent rotation around two orthogonal axes within the same physical space. The kinematic principle can be conceptualized using rotation matrices. For a joint with two rotational degrees of freedom—say, rotation about the X-axis by an angle $\alpha$ and about the Y-axis by an angle $\beta$—the combined rotation matrix $R$ describing the orientation of the output link relative to the base is given by the product of elementary rotations. While the order matters, a common sequence is:

$$ R_{total} = R_y(\beta) \cdot R_x(\alpha) $$

Where:

$$ R_x(\alpha) = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \cos\alpha & -\sin\alpha \\ 0 & \sin\alpha & \cos\alpha \end{bmatrix}, \quad R_y(\beta) = \begin{bmatrix} \cos\beta & 0 & \sin\beta \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ -\sin\beta & 0 & \cos\beta \end{bmatrix} $$

A traditional joint assembly uses two separate actuators, each responsible for generating one of these rotations through a series of linkages and reducers. In contrast, a spherical gear-based joint aims to achieve this composite motion through a direct, integrated mechanical transmission. The fundamental relationship between the input driver rotations ($\theta_1$, $\theta_2$) and the output orientation angles ($\alpha$, $\beta$) is governed by the unique geometry of the spherical gear meshing. This can be modeled as a nonlinear mapping function $f$:

$$ (\alpha, \beta) = f(\theta_1, \theta_2; G) $$

Here, $G$ represents the geometric parameters of the spherical gear, such as its pitch sphere radius, tooth profile, and number of teeth. The exact form of $f$ is complex and derived from the contact kinematics between the spherical gear and its mating components, often a set of enveloping pinions or differential gears. The torque transmission capability is another critical metric. For a spherical gear joint, the output torque vector $\vec{\tau}_{out}$ is related to the input torque vector $\vec{\tau}_{in}$ through the Jacobian matrix $J$ of the mechanism, which is a function of the instantaneous configuration:

$$ \vec{\tau}_{out} = J^T(\alpha, \beta) \cdot \vec{\tau}_{in} $$

The design goal is to maximize the determinant of $J$ across the workspace to ensure good force transmission and avoid singularities. The compactness stems from the fact that the spherical gear consolidates the functionality of two traditional reducers into one volume. The weight reduction is significant, as expressed by the comparative density equation. If a traditional dual-axis joint has mass $m_{traditional} = m_1 + m_2 + m_{structure}$, a spherical gear joint might have mass $m_{spherical} \approx k \cdot (m_1 + m_2)$, where $k < 1$ due to shared housing and eliminated redundant parts. This directly improves the robot’s dynamic performance, as the required actuator torque for limb acceleration is proportional to the moment of inertia: $\tau = I \cdot \dot{\omega}$. A lighter joint lowers $I$, enabling faster, more energy-efficient movements.

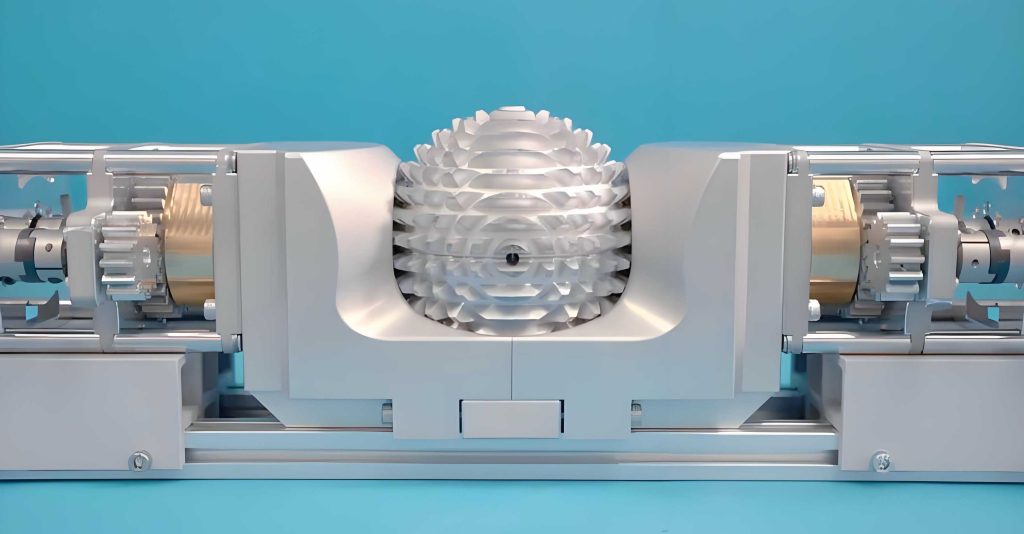

The visual representation above illustrates the intricate and compact nature of a spherical gear assembly. Observing such a design, one can appreciate the spatial efficiency it brings to a robot joint. The journey to realize such a component in durable, high-precision metal has been formidable. The manufacturing challenges are immense. The spherical gear tooth surface is a complex 3D sculpted form requiring micron-level accuracy across its entire curvature. This eliminates conventional gear hobbing or shaping methods. The only viable production tool is a high-precision five-axis computer numerical control (5-axis CNC) machining center. The machining path planning involves simultaneous interpolation along all five axes to follow the contoured surface. The toolpath generation must account for tool orientation, step-over distance to maintain surface finish, and avoidance of collisions with the complex workpiece geometry. The relationship between the machine’s tool center point (TCP) position $\vec{P}(t) = [x(t), y(t), z(t)]^T$ and orientation $\vec{O}(t) = [i(t), j(t), k(t)]^T$ as a function of time $t$ is governed by the spherical gear’s digital model, often defined by a parametric equation $\vec{S}(u,v)$:

$$ \vec{S}(u,v) = \begin{bmatrix} R \cdot \cos(u) \cdot \sin(v) \\ R \cdot \sin(u) \cdot \sin(v) \\ R \cdot \cos(v) \end{bmatrix} + \delta(u,v) \cdot \hat{n}(u,v) $$

where $R$ is the pitch sphere radius, $(u,v)$ are spherical coordinates, $\delta(u,v)$ defines the tooth profile modulation, and $\hat{n}(u,v)$ is the surface normal vector. The 5-axis CNC machine must precisely control its axes to mill this surface from a solid blank. The required positioning accuracy, often within a few micrometers, places this technology at the apex of advanced manufacturing, sometimes referred to as the “crown jewel” of machine tools.

The global race to master and industrialize spherical gear technology has intensified recently. Internationally, significant strides have been made in moving from academic prototypes using polymer 3D printing to durable metal versions suitable for rigorous robotic applications. This transition from lab to factory floor marks a critical maturation point for the spherical gear. Parallel to these developments, and of paramount strategic importance, has been the independent mastery of this technology within other major research and industrial ecosystems. Achieving domestic capability in designing, manufacturing, and controlling spherical gear joints is viewed as essential to avoid future dependencies and to foster innovation in local robotics industries. The ability to produce these core components internally signifies a leap in technological sovereignty.

The advantages of the spherical gear for humanoid robots are profound and multi-faceted. To elucidate these benefits systematically, the following table contrasts a hypothetical spherical gear joint against a conventional dual-harmonic drive joint for a similar payload capacity.

| Performance Metric | Conventional Dual-Harmonic Drive Joint | Spherical Gear-Based Joint | Impact on Humanoid Robot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Components | 2 harmonic reducers, 2 motors, housings, couplings, bearings. | 1 spherical gear assembly, 2 motors (integrated differential), compact housing. | Simplified assembly, higher reliability, lower part count. |

| Volume & Weight | Larger volume $V_c$, higher mass $m_c$ due to stacking. | Estimated 30-50% reduction in volume $V_s$, proportional mass reduction $m_s$. | More slender limb design, lower inertia, improved power-to-weight ratio. |

| Degrees of Freedom | 2 (achieved via two independent, serial single-DoF axes). | 2 (inherent, concurrent motion from a single integrated mechanism). | More natural, coordinated motion mimicking ball-and-socket joints. |

| Transmission Stiffness | High per axis, but system stiffness can be compromised by serial connection. | Potentially very high direct-drive stiffness due to integrated gear mesh. | Better positional accuracy, reduced oscillation, improved force control. |

| Control Complexity | Two independent servo loops, requires coordination and kinematic transformation. | Two-input, two-output coupled control. Requires precise model of spherical gear kinematics $f$. | Control algorithm is more integrated but demands accurate dynamic model of the spherical gear transmission. |

| Heat Dissipation | Two heat sources (motors/reducers) in proximity, challenging thermal management. | Potentially lower heat generation due to reduced friction and higher efficiency in a single transmission path. | Longer continuous operation, reduced need for active cooling in joints. |

| Backlash | Accumulated backlash from two reducer stages. | Can be minimized through precision manufacturing and preload in the spherical gear mesh. | Superior motion smoothness and precision, crucial for delicate tasks. |

The application spectrum for spherical gears extends far beyond humanoid robotics. Their unique properties make them ideal for scenarios requiring compact, multi-directional torque transmission in confined spaces. In satellite systems, spherical gears could drive solar panel arrays needing to track the sun across two axes with minimal mass and high reliability. In medical devices, such as advanced prosthetic limbs or surgical robotic end-effectors, the smooth, precise, and compact nature of spherical gear joints would enable more dexterous and natural movements. The field of semiconductor manufacturing, with its demand for ultra-precise, clean, and reliable motion in equipment like wafer handlers, represents another promising frontier. The potential of spherical gear technology is vast and largely untapped.

However, the path to widespread adoption is paved with technical hurdles that must be systematically overcome. The first is the design and analysis of the spherical gear pair itself. The tooth contact analysis (TCA) for a spherical gear is exponentially more complex than for spur or bevel gears. It involves solving for the continuous contact condition between two complex surfaces under load. The pressure distribution $\sigma(\vec{r})$ across the tooth contact area $A_c$ must be optimized to prevent premature wear or pitting. This requires solving the elasticity contact problem, often approximated by Hertzian theory for simpler geometries but requiring finite element analysis (FEA) for spherical gears:

$$ \nabla \cdot \sigma(\vec{r}) = 0 \quad \text{within the contact bodies} $$

with boundary conditions $\sigma \cdot \hat{n} = 0$ on free surfaces and displacement compatibility at the contact interface. The goal is to maximize the load capacity $F_{max}$ while minimizing stress concentrations. The second major challenge is the supporting mechanical architecture. A functional joint requires more than just the spherical gear. It typically involves a differential gear system to combine the inputs from two servo motors into the coordinated motion of the spherical gear. A basic differential for two inputs ($\omega_1$, $\omega_2$) generating two output rotations ($\omega_\alpha$, $\omega_\beta$) can be modeled by a linear transformation:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} \omega_\alpha \\ \omega_\beta \end{bmatrix} = D \cdot \begin{bmatrix} \omega_1 \\ \omega_2 \end{bmatrix} $$

where $D$ is a 2×2 matrix determined by the differential’s gear ratios. Integrating this seamlessly with the spherical gear is a key design task. Third, the control system must account for the nonlinear kinematics and potential dynamic coupling. A standard PID controller might be insufficient. A more robust approach involves computed-torque control or model predictive control (MPC). The control law $u(t)$ for the motor currents might be derived from the inverse dynamics model:

$$ u(t) = M(q) \ddot{q}_d + C(q, \dot{q}) \dot{q}_d + G(q) + K_p e + K_d \dot{e} $$

where $q = [\alpha, \beta]^T$ is the joint angle vector, subscript $d$ denotes desired values, $e$ is the tracking error, $M$ is the inertia matrix, $C$ captures Coriolis and centrifugal forces, $G$ is gravity, and $K_p$, $K_d$ are gain matrices. For a spherical gear joint, deriving accurate expressions for $M$, $C$, and $G$ that include the transmission’s inertia and friction characteristics is essential.

The manufacturing breakthrough, therefore, is twofold: creating the machine tools capable of making the spherical gear, and mastering the process to do so consistently and cost-effectively. The availability of domestically developed, high-precision, and affordable five-axis CNC machines is a critical enabler. It dramatically lowers the barrier to experimenting with and producing spherical gear prototypes and small batches, fostering innovation. The economic equation is compelling: if the cost of the key manufacturing equipment can be reduced significantly compared to imported alternatives, it accelerates the entire ecosystem’s ability to iterate and improve spherical gear designs. This virtuous cycle of accessible advanced manufacturing tools leading to better core components, which in turn enable superior robots, is a powerful driver for technological leadership.

Looking ahead, the research and development trajectory for spherical gear technology is vibrant. Several key areas demand focused attention. Material science is one: exploring advanced alloys, composites, or even ceramic materials for spherical gears could push the boundaries of strength-to-weight ratio and wear resistance. Surface engineering, such as applying diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings, could further reduce friction and increase longevity. The tribological performance of the spherical gear mesh, characterized by the coefficient of friction $\mu$ and wear rate $W$, will be a major factor in determining maintenance intervals and lifetime. Another frontier is the integration of sensing directly into the spherical gear joint. Embedding miniature strain gauges or utilizing fiber Bragg grating sensors within the gear structure could enable direct measurement of transmitted torque and contact forces, leading to highly responsive force control and condition monitoring. The data stream from such a joint, $S(t) = \{\alpha(t), \beta(t), \tau_\alpha(t), \tau_\beta(t), T(t)\}$ (where $T$ is temperature), would provide rich feedback for adaptive control algorithms.

Furthermore, the design philosophy of spherical gears could inspire entirely new robotic morphologies. Beyond mimicking human ball-and-socket joints, they could enable novel locomotion schemes for robots operating in unstructured environments. Imagine a multi-legged robot where each leg terminates in a spherical gear-based “ankle” allowing omnidirectional steering, or a snake-like robot with a continuous backbone of miniature spherical gear modules providing fluid, 3D bending motion. The mathematical modeling for such systems would involve complex, underactuated, or hyper-redundant kinematics, opening new chapters in robotics theory. The spherical gear, in essence, provides a fundamental building block for constructing sophisticated spatial mechanisms.

In conclusion, the emergence and ongoing refinement of spherical gear technology represent a quantum leap for robotic articulation, particularly for the ambitious field of humanoid robotics. My assessment, grounded in the principles of mechanics, manufacturing, and systems engineering, is that this technology addresses the core deficiencies of traditional joint architectures head-on. By offering dual rotational degrees of freedom in a compact, efficient, and high-torque package, the spherical gear unlocks new potentials for agility, strength, and energy economy in robots. The simultaneous progress in its advanced manufacturing—making the precise fabrication of spherical gears more accessible—is equally vital. This convergence of design innovation and production capability is creating a fertile ground for a new generation of robots. While challenges in precise control, durability validation, and system integration remain, the path forward is clear. The spherical gear is not just another component; it is a foundational technology that will underpin the dexterity and autonomy of future intelligent machines, reshaping industries from manufacturing and logistics to healthcare and space exploration. The race to master and deploy spherical gears is, in many ways, a race to define the next era of robotics.