In the realm of precision motion control and power transmission, I have long been fascinated by the innovative mechanism known as the strain wave gear. This unique drive system relies on controlled elastic deformation to achieve motion transfer, offering a paradigm shift from traditional rigid gear systems. The core advantages of strain wave gears, such as compact structure, high reduction ratios, exceptional positional accuracy, substantial load capacity, minimal backlash, and the ability to transmit motion into sealed spaces, have propelled their adoption across diverse fields. These include aerospace, robotics, medical devices, optical instruments, and automotive systems. The performance and reliability of a strain wave gear are profoundly influenced by the geometry of its teeth—the tooth profile. Therefore, in this article, I will provide a comprehensive overview of the research and development journey of tooth profiles for strain wave gears, drawing from historical progress, theoretical analyses, and practical applications. I will employ tables and mathematical formulations to synthesize key concepts, aiming to elucidate the evolution and current state of this critical technology.

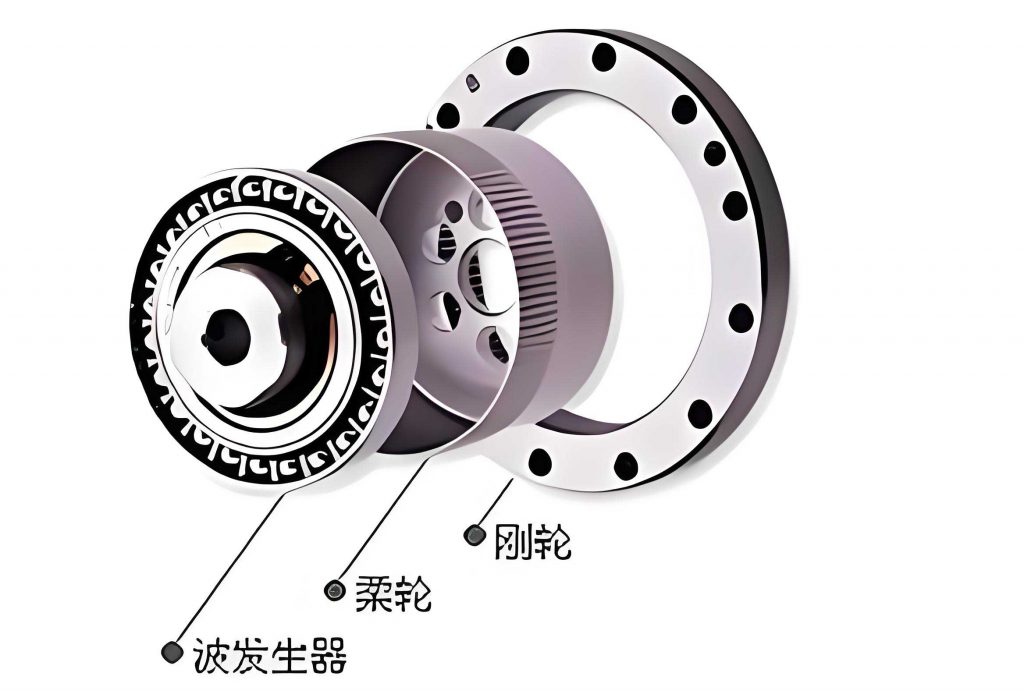

The fundamental operation of a strain wave gear involves three primary components: a rigid circular spline (the “rigid” gear), a flexible spline (the “flexspline” or “flexible” gear), and a wave generator. The wave generator, often an elliptical cam or a multi-roller assembly, deforms the flexible spline into a non-circular shape, causing its teeth to engage with those of the rigid spline at two diametrically opposite regions. As the wave generator rotates, the engagement zones travel, resulting in a relative rotation between the flexible and rigid splines. The kinematic relationship, which is central to the design of any strain wave gear, is given by the basic transmission ratio formula:

$$ i = \frac{\omega_{wg}}{\omega_{fs}} = -\frac{z_r}{z_r – z_f} $$

where \( i \) is the reduction ratio, \( \omega_{wg} \) is the angular velocity of the wave generator, \( \omega_{fs} \) is the angular velocity of the flexible spline, \( z_r \) is the number of teeth on the rigid spline, and \( z_f \) is the number of teeth on the flexible spline. The negative sign indicates opposite directions of rotation. Achieving smooth, efficient, and precise motion under load hinges on the design of the tooth profiles that mesh in these moving engagement zones. My exploration begins with the earliest attempts to define a suitable tooth form for the strain wave gear.

The inception of the strain wave gear is credited to its inventor, who proposed an initial tooth profile characterized by a high-pressure-angle straight-sided form. The rationale was twofold: to approximate a constant velocity ratio and to promote surface contact for enhanced load capacity. This design was predicated on the assumption that the neutral curve of the deformed flexible spline followed an Archimedean spiral. However, this model was an oversimplification, as it neglected critical factors such as tangential displacements along the neutral curve and the rotation of the tooth centerline due to curvature changes during deformation. Consequently, this early straight-sided profile, while groundbreaking, introduced inherent kinematic inaccuracies and suboptimal contact conditions. This realization sparked decades of rigorous research into the meshing theory of strain wave gears, shifting focus from purely geometric approximations to more sophisticated analyses of conjugate action.

A significant portion of my research and the wider engineering community’s efforts have been devoted to the involute tooth profile. The adoption of the involute for strain wave gears was driven largely by practical manufacturing considerations. When tooth counts are high, the involute curve approximates a straight line, and the vast existing infrastructure for machining involute gears could be adapted. Involute profiles for strain wave gears are generally categorized into two types: narrow-gap teeth and wide-gap teeth. The narrow-gap variant, where the space at the root circle is much smaller than the tooth thickness, became widely used due to its manufacturing ease. The wide-gap variant, with a root gap comparable to or larger than the tooth thickness, represents a form of profile modification (reduced addendum) intended to alleviate root stress concentration in the flexible spline.

My analytical and experimental studies on involute-profile strain wave gears reveal a critical characteristic. Under no-load conditions, only a limited number of tooth pairs are in simultaneous contact. When transmitting nominal torque, the number of contacting pairs increases significantly due to elastic deformation of the teeth and the flexible spline body, but this contact often occurs at the tooth edges. This edge contact is detrimental as it hinders the formation of a protective lubricant film and leads to elevated contact stresses. Therefore, profile modification or “crowning” of the involute teeth is typically necessary to centralize the contact area under load. The standard involute curve is defined parametrically:

$$ x = r_b (\cos \theta + \theta \sin \theta) $$

$$ y = r_b (\sin \theta – \theta \cos \theta) $$

where \( (x, y) \) are the coordinates of the involute, \( r_b \) is the base circle radius, and \( \theta \) is the roll angle. For a strain wave gear, the effective pressure angle and module must be carefully selected based on the deformation characteristics of the specific wave generator. The following table summarizes key comparative aspects of involute profiles in strain wave gear applications.

| Aspect | Narrow-Gap Involute | Wide-Gap/Modified Involute |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Motivation | Manufacturing convenience, direct use of standard gear tools. | Reduction of flexspline root stress, improved fatigue life. |

| Contact Pattern (No-load) | Limited line contact at a few teeth. | Similar limited contact. |

| Contact Pattern (Loaded) | Increased but often edge contact; requires crowning. | More centralized contact possible with proper modification. |

| Transmission Error | Can be minimized with precise manufacturing and assembly. | Potentially lower due to better load distribution. |

| Typical Applications | General-purpose strain wave gear reducers where cost is key. | Applications demanding higher torque capacity and longevity. |

Despite its widespread use, I must emphasize that the involute profile is not a theoretically ideal conjugate profile for the strain wave gear’s unique kinematic conditions. The motion trajectory of the flexible spline tooth relative to the rigid spline is complex, and true continuous conjugate action across the entire engagement arc is not naturally provided by the involute. The multi-tooth engagement in a loaded involute-based strain wave gear often relies on “point-of-contact” conditions facilitated by elastic deformations, which, while functional, limits the ultimate performance envelope. This understanding paved the way for the pursuit of purpose-designed tooth profiles.

A revolutionary advance in strain wave gear tooth design emerged with the development of the so-called “S” tooth profile. This profile was conceived from a fundamentally different premise: to achieve continuous, multi-tooth contact across the entire engagement zone without relying on load-induced deformation. The core idea involves generating the rigid spline tooth profile based on the envelope of the family of curves traced by the tip of the flexible spline tooth during its relative motion. This method aims to guarantee conjugate action. The name “S” derives from the distinctive shape of the working flank, which resembles the letter S or is composed of connected circular arcs.

In my analysis of the S-tooth strain wave gear, the theoretical foundation involves a mapping process. Let the position of a point on the flexible spline tooth be defined in its own coordinate system. As the wave generator rotates, this point moves relative to the rigid spline. The envelope condition is derived from the requirement that at the point of contact, the relative velocity vector is orthogonal to the common normal vector. For a point on the tooth tip curve of the flexible spline, its trajectory family can be described. The condition for the envelope (the rigid spline profile) is given by solving the system:

$$ \mathbf{r}_f(u, \phi) = \text{Transformation}(\phi) \cdot \mathbf{r}_f^0(u) $$

$$ \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_f}{\partial u} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}_f}{\partial \phi} = \mathbf{0} $$

where \( \mathbf{r}_f \) is the position vector in the rigid spline frame, \( u \) is a tooth profile parameter, \( \phi \) is the wave generator rotation angle, and \( \mathbf{r}_f^0 \) is the initial tooth profile. The S-profile is designed to satisfy this condition approximately for the intended operating range. Subsequent refinements led to profiles where the working flank comprises two circular arcs with large radii near the tip and root, connected smoothly. The primary performance benefits I have observed from literature and theoretical models include a significant increase in the simultaneous contact ratio, more uniform load distribution, reduced transmission error, and consequently, higher torsional stiffness and torque capacity. The following formula approximates the contact ratio \( \epsilon \) for an S-tooth strain wave gear, which is notably higher than for traditional profiles:

$$ \epsilon_S \approx \frac{\Delta \phi_{eng}}{\Delta \phi_{pitch}} $$

where \( \Delta \phi_{eng} \) is the angular extent of continuous engagement and \( \Delta \phi_{pitch} \) is the angular pitch. While the S-tooth profile represents a major leap, its design often assumes high tooth counts (approaching a rack-and-pinion analogy), which can introduce errors in strain wave gears with lower tooth numbers. Furthermore, the precise mathematical definition and manufacturing of the S-profile require advanced computational and fabrication techniques.

Parallel to the development of involute and S-profiles, extensive research has been conducted on circular arc tooth profiles for strain wave gears. The motivation for using circular arcs is compelling: they offer superior resistance to bending stress due to their thickened root section, facilitate the formation of a favorable wedge-shaped lubricant film, and can be designed to avoid edge contact. The circular arc profile, especially in its double-arc form, has been successfully implemented in high-performance strain wave gear sets. The basic geometry involves a convex arc on the rigid spline tooth and a conjugate concave arc (or a composite arc) on the flexible spline tooth. The design challenge lies in determining the arc parameters—radius \( R \) and center coordinates—that provide near-conjugate motion over the operating range of the strain wave gear.

For a circular arc profile, the condition of contact can be expressed using the theory of gearing. The common normal at the point of contact must pass through the instantaneous center of relative motion (the pitch point). For a given circular arc on the flexible spline defined by its center \( C_f(x_c, y_c) \) and radius \( R_f \), the corresponding point on the rigid spline profile \( \mathbf{r}_r(\psi) \) must satisfy:

$$ \mathbf{n}_f \cdot \mathbf{v}_{fr} = 0 $$

where \( \mathbf{n}_f \) is the normal vector to the flexible spline tooth arc, and \( \mathbf{v}_{fr} \) is the relative velocity vector of the contact point. Solving this equation for the rigid spline profile leads to a curve that is generally not a simple circular arc but can be closely approximated by one for practical purposes. Common implementations include the single circular arc, the tangent-connected double circular arc, and the stepped double circular arc. The tangent-connected double circular arc profile for the flexible spline, for instance, features two arcs—one near the tip and one near the root—connected smoothly at a common tangent point. This design aims to optimize contact stress distribution and bending strength. A comparative analysis of circular arc profiles is essential for selecting the right design for a strain wave gear application.

| Circular Arc Profile Type | Typical Configuration | Key Advantages | Key Challenges | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Circular Arc | One concave arc on flexspline, one convex arc on rigid spline. | Simplicity, good bending strength. | Shorter effective contact line, requires precise conjugate design. | |

| Tangent-Connected Double Circular Arc | Two arcs on flexspline flank with a smooth internal tangent. | Longer contact path, better stress distribution, improved lubrication. | More complex design and tooling; two arc radii and centers to optimize. | |

| Stepped Double Circular Arc | Two arcs with a discrete step or transition. | Can provide relief for stress concentration. | Potential for impact at the transition point under load. |

The adoption of circular arc profiles in industrial strain wave gear products has demonstrated tangible benefits, particularly in robotic joints where high torsional stiffness and compactness are paramount. However, a significant practical hurdle is the need for specialized cutting tools or grinding wheels to produce these non-involute shapes, increasing manufacturing cost. To circumvent this, “substitute” profiles, such as cycloidal-like shapes machinable with straight-sided tools, have been explored. These retain some advantages of the circular arc while easing production. In my view, the ongoing development of efficient and cost-effective manufacturing processes for circular arc profiles is as crucial as the theoretical design work itself for the widespread adoption of high-performance strain wave gears.

Beyond these major categories, research into novel tooth profiles for strain wave gears continues. This includes investigations into modified cycloidal profiles, polynomial curves optimized via finite element analysis for minimum stress, and even non-symmetric profiles tailored for unidirectional high-torque applications. The design process is increasingly supported by sophisticated computer-aided engineering (CAE) tools. Multi-objective optimization algorithms are employed to simultaneously maximize load capacity, minimize transmission error, and ensure manufacturability. The objective function \( F \) for such an optimization might look like:

$$ F(\mathbf{p}) = w_1 \cdot \sigma_{max}^{-1}(\mathbf{p}) + w_2 \cdot TE^{-1}(\mathbf{p}) + w_3 \cdot \kappa(\mathbf{p}) $$

where \( \mathbf{p} \) is a vector of tooth profile parameters (e.g., pressure angles, arc radii, modification coefficients), \( \sigma_{max} \) is the maximum contact or bending stress, \( TE \) is the transmission error, \( \kappa \) is a manufacturability index, and \( w_i \) are weighting factors. This computational approach allows for the exploration of a vast design space beyond classical geometric forms.

The impact of tooth profile selection on the overall system dynamics of a strain wave gear cannot be overstated. The profile directly influences key performance metrics which I have summarized in the following comprehensive table, providing a side-by-side comparison of the three major profile families discussed.

| Performance Metric | Involute Profile | S-Tooth Profile | Circular Arc Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Conjugacy | Low. Approximate, relies on deformation for multi-tooth contact. | High. Designed for near-conjugate action in the engagement zone. | Medium to High. Can be designed for good conjugacy with proper arc parameters. |

| Simultaneous Contact Ratio | Moderate (highly load-dependent). | High (intrinsically designed). | High (due to favorable flank geometry). |

| Load Distribution | Often uneven, prone to edge contact. | Very uniform across engaged teeth. | Uniform, with good centralization of contact. |

| Torsional Stiffness | Good, but can be limited by edge contact. | Excellent due to continuous multi-tooth engagement. | Excellent, particularly with double-arc designs. |

| Transmission Error & Backlash | Can be made very low with precision manufacturing and preload. | Potentially the lowest, due to conjugate design. | Very low, contributing to high positional accuracy. |

| Stress in Flexspline Tooth | Higher bending stress at root; sensitive to fillet design. | Well-distributed, generally lower peak stress. | Excellent bending strength due to thick root; low stress concentration. |

| Manufacturing Complexity & Cost | Lowest. Utilizes standard gear production technology. | High. Requires specialized design software and non-standard tooling/machining. | Medium to High. Needs special cutters/grinding wheels, but processes are established. |

| Primary Application Focus | Cost-sensitive, general industrial automation, where volume production benefits from standard tools. | High-end robotics, aerospace actuators, precision instruments where performance is critical. | Industrial robots, space mechanisms, high-torque compact drives requiring durability and stiffness. |

In conclusion, my journey through the evolution of strain wave gear tooth profiles reveals a clear trajectory from pragmatic adoption of existing geometries (involute) toward sophisticated, purpose-engineered solutions (S-tooth and circular arc) that unlock the full potential of the strain wave gear principle. The choice of tooth profile is a critical design decision that balances kinematic correctness, mechanical strength, manufacturing feasibility, and cost. The ongoing research, increasingly powered by computational optimization and advanced material science, continues to push the boundaries. New developments in additive manufacturing may further revolutionize how complex, optimized profiles for strain wave gears are produced. As demands for precision, compactness, and reliability grow in fields like collaborative robotics, satellite mechanisms, and surgical devices, the incentive to develop and implement advanced tooth profiles for strain wave gears will only intensify. Therefore, I believe that sustained investment in both the theoretical understanding and practical fabrication of these profiles is essential for the next generation of high-performance motion control systems.