The end effector is the terminal component of a robotic manipulator that interacts directly with the workpiece or environment. It serves as a critical interface, translating the robot’s programmed motions into tangible actions such as gripping, welding, painting, or assembling. Its performance is paramount, as any failure directly halts the production process. The operational integrity of the end effector directly influences production line stability, product quality, and overall equipment effectiveness (OEE).

From my experience in industrial automation, the challenges in maintaining these components are multifaceted. Modern production demands near-continuous operation, making rapid fault diagnosis and efficient repair not just beneficial but essential. This article synthesizes field observations and maintenance logic into a structured framework. I will analyze the current landscape of end effector maintenance, introduce a multidimensional classification system for faults, and explore how this framework informs strategic maintenance decisions, supported by analytical models and case-derived insights.

The Maintenance Landscape for Industrial Robot End Effectors

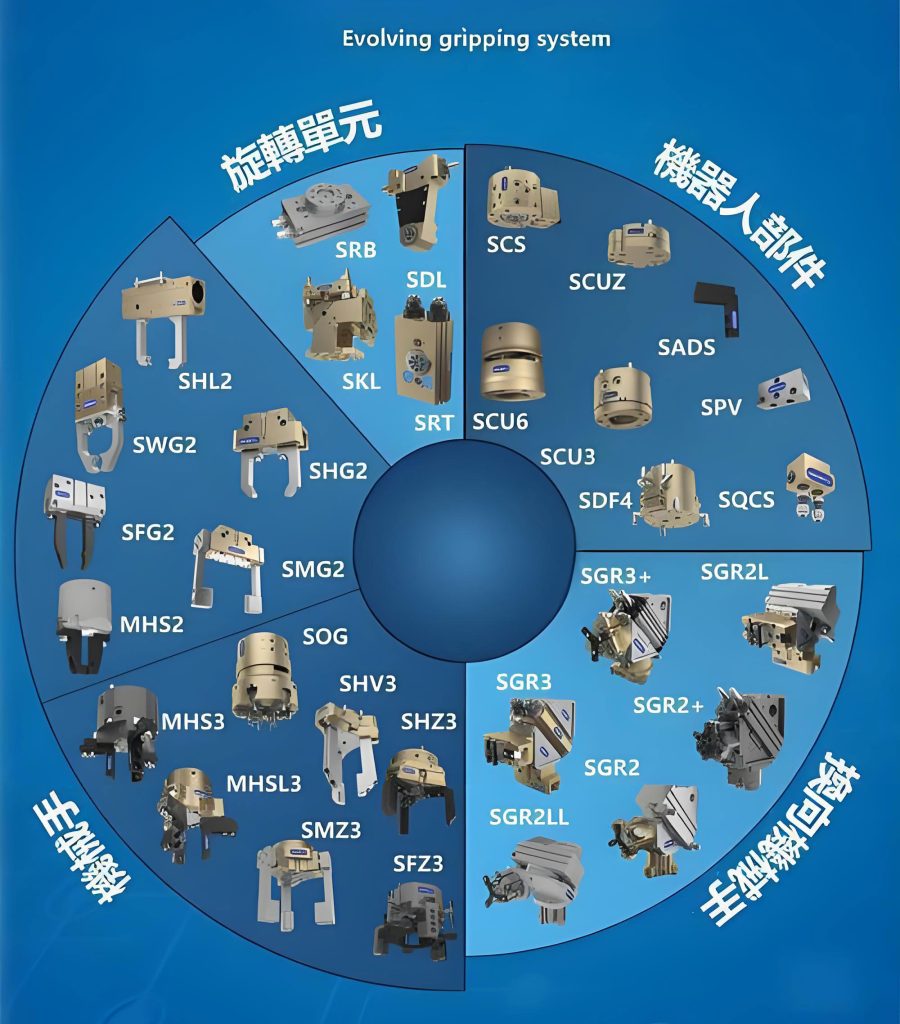

The approach to maintaining an end effector is fundamentally shaped by its design philosophy and integration level. A primary distinction lies between standardized and custom-built units.

| End Effector Type | Characteristics | Maintenance Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized End Effector | Off-the-shelf design, moderate cost, limited application scope but good within its range. | Faster diagnosis due to known failure modes. Lower spare part cost and easier procurement. Repair procedures are often documented. |

| Custom-Built End Effector | Tailored for specific tasks, high complexity and initial cost, optimal for niche applications. | Diagnosis requires deep system understanding. Spare parts may be proprietary or have long lead times. Repair strategies often need to be developed in-house. |

Regardless of type, effective troubleshooting rests on a solid theoretical foundation. One must understand not only the robot’s kinematics and control but also the specific end effector’s actuation principle (pneumatic, electric, hydraulic), transmission mechanism, sensor feedback (force, torque, vision), and its integration with the robot controller. This knowledge is the map that guides the diagnostic journey. The general maintenance workflow, as practiced on the floor, follows a logical sequence: observation of symptoms, root cause analysis, strategy formulation, corrective action, and verification. This process consistently reveals interconnected factors contributing to a failure.

A Five-Dimensional Framework for End-Effector Fault Analysis

Through the systematic review of maintenance logs and incident reports, I have identified five core dimensions that collectively describe any end effector fault. This framework moves beyond a simple symptom-fix approach to a more analytical one.

| Dimension | Description | Common Manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Fault Phenomenon | The observable symptom or system alarm. | Loss of grip force, positional deviation, excessive vibration, actuator stalling, sensor failure alarm. |

| 2. Fault Type | The categorical nature of the failed subsystem. | Mechanical (wear, breakage), Electrical (short circuit, signal loss), Pneumatic/Hydraulic (leak, pressure drop), Control (parameter drift, software bug). |

| 3. Root Cause | The fundamental origin of the failure. | Design flaw, material fatigue, improper operation, inadequate lubrication, software error. |

| 4. Environmental Context | External conditions influencing the failure. | Temperature extremes, conductive dust, chemical corrosion, coolant/oil ingress, mechanical impact. |

| 5. Failure Frequency | The rate of occurrence over time. | Sporadic (once), Intermittent (random), Chronic (repeating at high rate). |

These dimensions are not independent. For instance, a Fault Phenomenon like “inconsistent weld quality” may stem from a Fault Type of mechanical wear in a torch cleaning unit (Root Cause: abrasive paper exhaustion), exacerbated by a dusty Environmental Context, leading to a gradually increasing Failure Frequency. Analyzing a fault through this multidimensional lens allows for a more precise diagnosis and a more strategic repair response.

Impact of Fault Dimensions on Maintenance Strategy Formulation

The identified dimensions directly inform the choice of maintenance strategy. The goal is to select the most efficient and cost-effective response, balancing immediate repair needs with long-term reliability. The influence matrix can be summarized as follows:

| Fault Dimension | Primary Influence on Strategy | Typical Strategic Response |

|---|---|---|

| Phenomenon & Type | Guides immediate diagnostic path and repair action. | Corrective Maintenance: Replace broken gear, reseal leaking cylinder, recalibrate sensor. |

| Root Cause | Determines if a one-time fix or a systemic change is needed. | Improvement Maintenance: Redesign a weak bracket, upgrade a substandard component, modify control logic. |

| Environmental Context | Highlights need for protective measures or condition monitoring. | Preventive Maintenance: Install protective bellows, add air filters, implement regular cleaning schedules. |

| Failure Frequency | Indicates the effectiveness of current strategies and signals aging or design issues. | Predictive Maintenance: Analyze trend data to schedule part replacement before failure; switch from time-based to condition-based maintenance. |

The strategic choice can be modeled as an optimization problem minimizing total cost. The total cost $C_{total}$ associated with an end effector fault is a function of repair cost, downtime cost, and potential quality loss:

$$ C_{total} = C_{repair} + C_{downtime} \cdot T_{repair} + C_{quality} $$

A strategic framework aims to minimize $C_{total}$. For a chronic fault (high Failure Frequency), a purely corrective strategy leads to a high cumulative $C_{total}$. Implementing an improvement strategy (addressing the Root Cause) may have a higher initial $C_{repair}$ but reduces $C_{downtime} \cdot T_{repair}$ over time, yielding a lower $C_{total}$. The optimal strategy $S^{*}$ for a fault described by dimension vector $\vec{D} = (Phenomenon, Type, Cause, Environment, Frequency)$ can be conceptualized as:

$$ S^{*} = \arg\min_{S \in \mathcal{S}} \mathbb{E}[C_{total}(S, \vec{D})] $$

where $\mathcal{S}$ is the set of all feasible maintenance strategies. In practice, a scoring system based on the fault dimensions helps select $S^{*}$. For example, a high score in Root Cause (design flaw) and Failure Frequency (chronic) strongly pushes the decision towards an Improvement strategy.

Systematic Case Studies in Strategy Selection

The following analysis synthesizes real-world scenarios to illustrate how the five-dimensional framework guides effective decision-making. These cases are generalized from field experience.

| Case Focus | Relevant Fault Dimensions | Analysis & Strategic Rationale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Servo Welding Gun Drift | Phenomenon: Weld spot position deviation. Type: Mechanical wear. Frequency: Increasing intermittently. |

Predictive & Improvement. Replaced wear-prone linear guides with a hardened version and instituted vibration monitoring trend analysis. | The Frequency dimension signaled a wear-out failure mode, not a random event. A corrective fix was insufficient. Predictive monitoring allowed planned intervention, and the improved component (addressing the Root Cause) extended the mean time between failures (MTBF), reducing long-term $C_{total}$. |

| 2. Gripper Force Loss in Machining Cell | Phenomenon: Part dropped during transfer. Type: Pneumatic. Environment: High humidity, fine abrasive dust. |

Preventive & Corrective. Cleaned and replaced the solenoid valve (Corrective). Installed a desiccant air filter and a protective skirt on the end effector (Preventive). | The Environmental Context was the key driver. A simple corrective repair would lead to quick recurrence. The combined strategy addressed the immediate fault and mitigated the environmental Root Cause, preventing a high Failure Frequency. |

| 3. Vision-Guided Screwdriver Error | Phenomenon: “Torque Not Reached” alarm. Type: Control/Electrical. Cause: Electrical noise on sensor signal. |

Improvement Maintenance. Rerouted sensor cabling away from power lines, added shielding, and adjusted the controller’s noise filtering parameters. | Intermittent alarms pointed to a Control type issue. The Root Cause (signal integrity) required an engineering improvement, not just part replacement. This solution targeted the underlying system vulnerability, effectively reducing the fault’s occurrence probability to near zero. |

The effectiveness of a chosen strategy can be quantified. For Case 1, if $MTBF_{old}$ was 400 hours and $MTBF_{new}$ becomes 1200 hours after improvement, and the mean time to repair (MTTR) is 2 hours with a downtime cost $C_{downtime}$ of $500/hour, the annual savings in downtime cost alone (assuming 8000 operational hours/year) would be:

$$ Savings = \left( \frac{8000}{MTBF_{old}} – \frac{8000}{MTBF_{new}} \right) \cdot MTTR \cdot C_{downtime} $$

$$ Savings = \left( \frac{8000}{400} – \frac{8000}{1200} \right) \cdot 2 \cdot 500 = (20 – 6.67) \cdot 1000 = \$13,330 $$

This simple calculation demonstrates the tangible impact of a dimension-informed strategy.

Towards a Proactive Maintenance Culture for End Effectors

The transition from reactive fixing to proactive management is the ultimate goal. The five-dimensional framework facilitates this by structuring data collection and analysis. Historical fault records should be tagged with these dimensions, enabling powerful analytics. For instance, Pareto analysis of Root Causes can identify the “vital few” design issues across a fleet of end effectors. Trend analysis of Failure Frequency for specific Fault Types can inform optimal spare part inventory levels using models like:

$$ \lambda(t) = \frac{\beta}{\alpha} \left( \frac{t}{\alpha} \right)^{\beta-1} $$

where $\lambda(t)$ is the failure rate, and $\alpha$ (scale) and $\beta$ (shape) parameters are estimated from historical time-between-failure data. A $\beta > 1$ indicates wear-out, justifying preventive replacement schedules.

Furthermore, this framework integrates with modern Industrial IoT (IIoT) platforms. Sensors can monitor the Environmental Context (temperature, particulate count) and Fault Phenomenon proxies (vibration amplitude, current draw). Machine learning algorithms can then correlate this real-time data with the historical dimension-based failure database to predict faults before they occur, enabling true predictive maintenance. For an electric gripper, a gradual increase in motor current required to achieve the same grip force could be an early Phenomenon dimension indicator of mechanical wear (Type), triggering an inspection work order.

In conclusion, viewing end effector faults through the intertwined lenses of Phenomenon, Type, Cause, Environment, and Frequency transforms maintenance from a tactical necessity into a strategic function. This structured approach enables faster diagnosis, more informed repair-or-improve decisions, and the systematic accumulation of knowledge that feeds back into better end effector design and maintenance policy. It is a powerful framework for ensuring that the critical final link in the robotic chain—the end effector—operates with the reliability and precision that modern automated manufacturing demands.