In the realm of precision mechanical transmission, strain wave gear systems, often referred to as harmonic gear drives, have garnered significant attention due to their unique capabilities. As a researcher deeply immersed in this field, I find the exploration of these systems both challenging and rewarding. The core innovation lies in the use of elastic deformation to achieve motion transmission, which offers distinct advantages such as high reduction ratios, compact design, and zero-backlash operation. However, with the advent of short-cup flexspline designs aimed at enhancing torsional stiffness and reducing axial dimensions, new challenges emerge, particularly concerning the preliminary deformation force and associated stresses. This study delves into the intricate behavior of the flexspline under initial deformation, employing finite element analysis to unravel the influence of geometric parameters. The ultimate goal is to provide insights that can guide the optimization of strain wave gear components for improved performance and longevity.

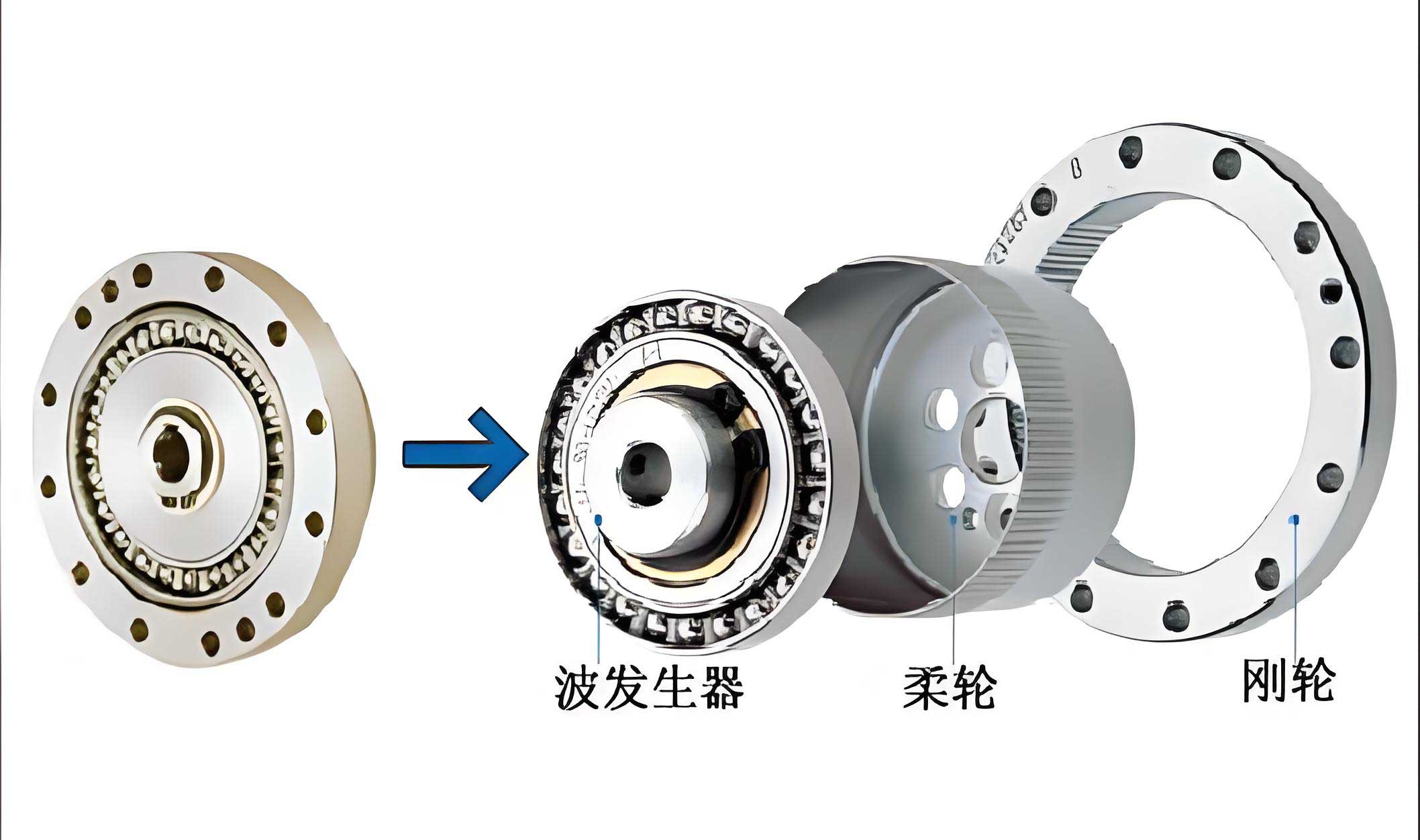

The strain wave gear mechanism operates on the principle of controlled elastic deformation. It typically consists of three primary components: a wave generator, a flexspline (a thin-walled cup with external teeth), and a circular spline (a rigid internal gear). When the wave generator, often an elliptical cam, is inserted into the flexspline, it forces the flexspline to conform to its shape, inducing a controlled deflection. This deflection causes the teeth of the flexspline to engage with those of the circular spline at specific points, enabling smooth torque transmission. The initial act of inserting the wave generator imposes a deformation on the flexspline even before any external load is applied, resulting in what we term the “preliminary deformation force.” This force is critical because it sets the stage for the stress state during operation, directly impacting fatigue life and reliability. In short-cup designs, where the length-to-diameter ratio (Lx) is reduced to around 0.5 or less, this preliminary deformation force can escalate dramatically, leading to heightened stress concentrations that threaten structural integrity. Understanding this phenomenon is paramount for advancing strain wave gear technology.

To systematically investigate the preliminary deformation force, we first establish a geometric model of the flexspline. Given the complexity of the toothed structure, it is common practice to simplify the flexspline into an equivalent smooth cylindrical shell for stress analysis. This simplification is based on the assumption that the tooth module is small and the number of teeth is large, allowing us to approximate the toothed section as a ring with an equivalent thickness. For this study, we focus on a strain wave gear with a two-wave elliptical cam wave generator. The flexspline’s geometry is defined by several parameters, each playing a role in its mechanical response. Below is a comprehensive table summarizing these geometric parameters and their symbols, which will be referenced throughout our analysis.

| Symbol | Description | Typical Value or Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| m | Module | 0.4 mm |

| z | Number of teeth | 200 |

| Xr | Modification coefficient | 3.85 |

| R1 | Transition radius at cup bottom | 3 mm |

| R2 | Transition radius at flange | 3 mm |

| R3 | Transition radius between tooth ring and cup body | 3 mm |

| BR | Width of tooth ring | 16 mm |

| BI | Distance from tooth ring to cup rim | 3 mm |

| R0 | Internal radius of flexspline | Derived: df/2 – H0 |

| Raa | Radius of equivalent smooth tooth ring | Derived: R0 + 2.286H0 |

| H | Thickness of flange at cup bottom | 5 mm |

| H0 | Wall thickness under tooth root | 0.6 + T/2 mm |

| T | Wall thickness of cup body | Variable (e.g., 0.4 mm) |

| L | Length of flexspline cup | Variable: Lx × dz |

| d1 | Inside diameter of flange | 26 mm |

| dT | Outside diameter of flange | 50 mm |

| d2 | Diameter of bolt hole circle on flange | 39 mm |

| d3 | Diameter of bolt hole | 5 mm |

| da | Addendum diameter of flexspline | Derived: dz + 2m(1 + Xr) |

| df | Dedendum diameter of flexspline | Derived: dz – 2m(1.35 – Xr) |

| dz | Pitch diameter of flexspline | Derived: m × z |

| w0 | Wave height | 0.4 mm |

| Lx | Length-to-diameter ratio of cup | Variable (e.g., 0.8) |

The theoretical foundation for analyzing the flexspline relies on shell theory, with several key assumptions to make the problem tractable. We assume the wave generator is a rigid body, the neutral axis of the cylindrical shell remains unchanged in length during deformation, and the elastic deformations are small. Under these conditions, the stress state in the flexspline can be described using thin-shell mechanics. For a cylindrical shell subjected to elliptical deformation, the bending moments and membrane forces contribute to the overall stress. The preliminary deformation force, denoted as Fr, arises from the resistance of the flexspline to this imposed shape change. In mathematical terms, the relationship between deformation and force can be approximated by considering the strain energy. For a simplified model, the force required to deform a thin-walled cylinder into an ellipse can be expressed as:

$$ F_r \propto \frac{E T^3 w_0}{R_0^3} f(L_x) $$

where E is the Young’s modulus of the material (taken as 2.1 × 105 N/mm² for typical steel), T is the wall thickness, w0 is the wave height, R0 is the internal radius, and f(Lx) is a function that captures the influence of the length-to-diameter ratio. This formulation highlights the cubic dependence on wall thickness and the inverse cubic dependence on radius, suggesting that even small changes in T can significantly affect Fr. However, this simplified model neglects edge effects and geometric discontinuities, which is why a detailed finite element analysis is indispensable for accurate predictions, especially in short-cup strain wave gear designs.

In our investigation, we employ the finite element method (FEM) to simulate the initial deformation of the flexspline. Using ANSYS software, we construct a three-dimensional model of one-quarter of the flexspline, leveraging symmetry to reduce computational cost. The model meshes with SOLID186 and SOLID187 elements, ensuring adequate resolution in critical areas like transition radii. The material properties are defined with a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3. The wave generator is modeled as a rigid elliptical surface that displaces the inner wall of the flexspline, simulating the insertion process. We then compute the reaction forces at the constraints to determine the preliminary deformation force. To isolate the effects of various geometric parameters, we conduct a series of parametric studies, varying one parameter at a time while keeping others at their default values (e.g., T = 0.4 mm, R1 = R2 = R3 = 3 mm, Lx = 0.8). The results are summarized in the table below, which quantifies how each parameter influences Fr.

| Parameter | Variation Range | Trend in Fr | Relative Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall Thickness (T) | 0.3 mm to 0.6 mm | Increases monotonically | High |

| Length-to-Diameter Ratio (Lx) | 0.4 to 1.2 | Decreases asymptotically; sharp rise for Lx < 0.5 | High |

| Cup Bottom Transition Radius (R1) | 1 mm to 5 mm | Minimal fluctuation | Low |

| Flange Transition Radius (R2) | 1 mm to 5 mm | Negligible change | Low |

| Tooth Ring Transition Radius (R3) | 1 mm to 5 mm | Slight increase with minor波动 | Low to Moderate |

The data clearly indicates that wall thickness and length-to-diameter ratio are the dominant factors governing the preliminary deformation force in strain wave gear flexsplines. As T increases, the flexspline becomes stiffer, requiring more force to achieve the same elliptical deformation. This relationship appears nonlinear, prompting further regression analysis. Conversely, as Lx increases, the flexspline behaves more like a long cylinder where end effects diminish, leading to a reduction in Fr. However, when Lx drops below 0.5, the short-cup geometry induces significant boundary constraints, causing Fr to escalate rapidly. This phenomenon underscores the trade-off in designing compact strain wave gear systems: reducing axial size to enhance torsional stiffness comes at the cost of higher initial stresses. The transition radii (R1, R2, R3) show minimal influence, suggesting that stress concentrations at these fillets are secondary to global bending effects in determining Fr. Nonetheless, they may affect fatigue life and should be optimized separately.

To formalize the relationships, we perform nonlinear regression analysis on the data for wall thickness and length-to-diameter ratio. For wall thickness (T), we test several function types—exponential, power, and S-curve—and evaluate their fit using the sum of squared errors (SSE). The exponential model provides the best approximation, yielding the following equation:

$$ F_r = 34.0997 \cdot e^{1.9276 T} $$

where Fr is in Newtons and T is in millimeters. This exponential growth aligns with the theoretical expectation that stiffness increases rapidly with thickness. For the length-to-diameter ratio (Lx), we explore hyperbolic, S-curve, exponential, power, and polynomial models. A fourth-degree polynomial offers an excellent fit, but a hyperbolic function also performs well for practical purposes. The hyperbolic regression equation is:

$$ \frac{1}{F_r} = 0.018 – \frac{0.004}{L_x} $$

which can be rearranged to express Fr directly:

$$ F_r = \frac{1}{0.018 – \frac{0.004}{L_x}} $$

For higher accuracy, the polynomial regression yields:

$$ F_r = 1914.8 L_x^4 – 6070.4 L_x^3 + 7215.6 L_x^2 – 3847 L_x + 858.5 $$

These equations provide valuable design tools for predicting the preliminary deformation force based on key geometric parameters in strain wave gear flexsplines. They highlight that in short-cup configurations (Lx ≈ 0.5), Fr can be several times higher than in traditional designs (Lx ≈ 1.0), emphasizing the need for careful material selection and fatigue analysis.

Beyond the finite element results, it is insightful to consider the broader implications for strain wave gear performance. The preliminary deformation force not only affects assembly but also sets the baseline stress state during operation. In a rotating strain wave gear system, the flexspline undergoes cyclic loading as the wave generator spins, leading to alternating stresses that can cause fatigue failure. The initial stress from Fr superimposes onto these operational stresses, potentially reducing the fatigue limit. We can estimate the maximum bending stress in the flexspline wall using beam theory on a curved beam. For an elliptical deformation, the circumferential bending stress σθ at the critical point (typically the long axis) can be approximated as:

$$ \sigma_\theta = \frac{M \cdot y}{I} $$

where M is the bending moment per unit length, y is the distance from the neutral axis (≈ T/2), and I is the moment of inertia per unit length (≈ T³/12). The moment M is related to the deformation curvature κ, which for an ellipse with wave height w0 and radius R0, is roughly κ ≈ w0/R0². Thus, we derive:

$$ \sigma_\theta \approx \frac{E T w_0}{2 R_0^2} $$

This stress increases linearly with wall thickness and wave height, but inversely with the square of the radius. In short-cup strain wave gear flexsplines, the stress may be amplified due to edge effects, which our FEM captures more accurately. To correlate stress with force, we note that Fr is essentially the integral of stress over the deformed area. A simplified relation might be:

$$ F_r \approx \sigma_\theta \cdot A_{eff} $$

where Aeff is an effective area dependent on Lx. Combining these expressions reinforces the critical role of T and Lx in determining both force and stress.

In practice, designing a strain wave gear involves balancing multiple constraints. For instance, increasing wall thickness boosts stiffness and load capacity but raises Fr and stress, possibly requiring stronger materials. Reducing Lx saves space and improves torsional rigidity but at the expense of higher initial deformation forces. Therefore, optimization algorithms can be employed to find Pareto-optimal solutions. We propose an objective function that minimizes Fr while maintaining stress below a fatigue limit, subject to geometric bounds. Such optimization would leverage the regression models we derived, enabling rapid prototyping and design iteration for advanced strain wave gear systems.

Furthermore, the material properties play a crucial role. While we assumed linear elastic behavior for steel, composite materials or advanced alloys could mitigate some issues. For example, materials with higher strength-to-weight ratios or better fatigue resistance could allow thinner walls, reducing Fr without compromising durability. Additionally, manufacturing tolerances and surface treatments affect stress concentrations, particularly at transition radii. Although our study shows R1, R2, and R3 have minor impact on Fr, they influence local stress peaks that initiate cracks. Hence, a holistic design approach should integrate geometric, material, and manufacturing considerations.

To validate our findings, experimental measurements on prototype strain wave gear flexsplines would be beneficial. Strain gauges could be installed on the outer surface to measure initial stresses after wave generator insertion, and force sensors could record Fr during assembly. Such data would corroborate the FEM predictions and regression models, building confidence in their use for industrial applications. Moreover, dynamic testing under load would reveal how preliminary deformation affects long-term performance, such as backlash variation and efficiency degradation.

In conclusion, this study underscores the significance of preliminary deformation force in strain wave gear flexsplines, especially for short-cup designs. Through finite element analysis and regression modeling, we have demonstrated that wall thickness and length-to-diameter ratio are the primary geometric drivers of this force. The exponential relationship with thickness and the hyperbolic or polynomial relationship with length-to-diameter ratio provide practical equations for designers. These insights enable more informed trade-offs in optimizing strain wave gear systems for applications ranging from robotics to aerospace, where compactness, precision, and reliability are paramount. Future work could explore nonlinear material models, dynamic effects, and multi-objective optimization to further advance the state of the art in strain wave gear technology.

Reflecting on the broader context, strain wave gears continue to evolve, with innovations like magnetic or piezoelectric wave generators emerging. However, the elastic flexspline remains at the heart of these systems, and its behavior under deformation is fundamental. By deepening our understanding of parameters like preliminary deformation force, we contribute to the development of more robust and efficient transmission solutions. I believe that continued research in this area will unlock new possibilities for miniaturization and performance enhancement, solidifying the role of strain wave gears in next-generation mechanical systems.