The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into healthcare represents one of the most transformative technological shifts of our era. At the forefront of this revolution are advanced medical robot systems, particularly surgical robots. These systems, transcending the passive role of traditional medical instruments, introduce a paradigm of enhanced precision, minimal invasiveness, and superior clinical outcomes. The global market for surgical robots is experiencing explosive growth, projected to reach tens of billions of dollars, driven by aging populations, rising surgical volumes, and significant governmental support, especially in burgeoning markets like China. However, this rapid ascent is accompanied by profound legal ambiguities. The core legal dilemma revolves around the fundamental status of the medical robot: is it merely a sophisticated tool, an object of property law, or does its growing autonomy warrant a reconceptualization of its legal personality? This question directly dictates the framework for assigning liability when harm occurs, challenging the foundations of existing tort law, which struggles to accommodate an entity that is part product, part agent, and potentially, part autonomous actor.

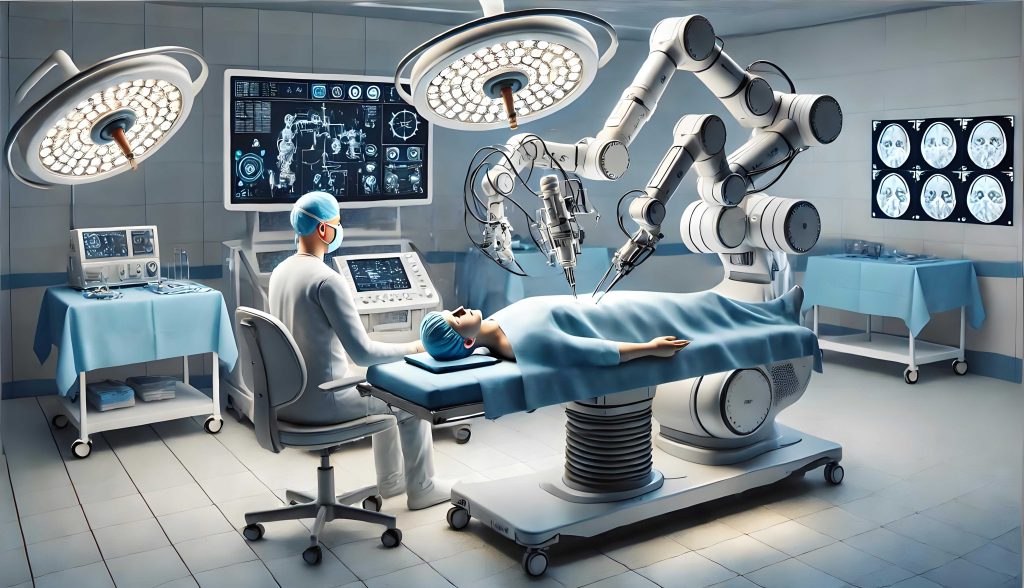

The archetype of contemporary robotic surgery is the master-slave telemanipulation system, such as the da Vinci Surgical System. It comprises a surgeon’s console, a patient-side cart with robotic arms, and a vision system. The surgeon operates from the console, with hand movements translated into precise, scaled, and tremor-filtered motions of the instruments inside the patient’s body. This represents a significant leap from earlier, simpler robotic aids used for stabilization. Yet, the horizon extends further toward greater autonomy. Research platforms like the Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot (STAR) have demonstrated the ability to perform complex soft-tissue surgery, such as intestinal anastomosis, with minimal human intervention, marking a decisive step toward autonomous surgical medical robot platforms.

Categorizing medical robot systems is essential for a nuanced legal analysis. One primary classification is based on the level of AI and autonomy:

- Non-autonomous (Teleoperated): The robot is a direct extension of the surgeon’s will (e.g., standard da Vinci procedures).

- Semi-autonomous: The robot executes pre-planned tasks or provides haptic feedback and guidance, but the surgeon retains primary control.

- Fully Autonomous (Non-conscious): The robot performs an entire surgical procedure based on AI-driven perception and decision-making without real-time human control, though it lacks consciousness (e.g., the envisioned future of systems like STAR).

Another crucial classification is by clinical application, as the risks and standards of care differ:

| Application Type | Examples | Key Legal Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Laparoscopic Robots | da Vinci system for prostatectomy, hysterectomy | Surgeon skill transfer, instrument failure, vision system error. |

| Orthopedic Robots | Robots for knee/hip arthroplasty, spinal surgery | Precision of bone cutting, registration accuracy, software planning errors. |

| Robots for Percutaneous Procedures | Robots for biopsy, ablation, stereotactic neurosurgery | Targeting accuracy, path planning, real-time adaptation to tissue movement. |

The distinctive nature of harm caused by a medical robot creates unique challenges for tort law:

- Complexity and the “Black Box” Problem: The intertwining of hardware, software, and machine learning algorithms creates a system of extreme complexity. When a failure occurs, attributing it to a specific mechanical fault, a software bug, a flawed design premise, or an emergent property of the AI’s learning is extraordinarily difficult. This opacity hinders both factual causation and legal attribution.

- The Autonomy Continuum: Unlike a scalpel, a medical robot possesses a degree of independence. In semi-autonomous modes, it may interpret sensor data and adjust its actions. A fully autonomous system makes its own intra-operative decisions. This autonomy disrupts the traditional, linear chain of liability from manufacturer to user to patient. Who is responsible when the critical error originates from the machine’s own “decision,” derived from its training data and algorithms, rather than from a manufacturing defect or a surgeon’s mistaken command?

- The Paramount Stakes: A malfunctioning medical robot operates inside a human body. The potential for catastrophic, irreversible harm to life and health is immediate and profound. This elevates the required duty of care for all parties involved—designers, manufacturers, regulators, and healthcare providers—to the highest level. The patient is in an exceptionally vulnerable position, unable to resist or correct the machine’s actions.

The central, unresolved legal question is the subject status of the medical robot. Is it an object (a “tool” or “product”) or a subject (an “electronic person” or “agent”)? Legal scholarship is divided, with theories ranging from “electronic personhood” and “limited legal personality” to “complex instrument” and “software agent.” Practical precedents are sparse but suggestive: a US regulatory body once considered an AI driving system as the “driver,” and a humanoid robot was granted symbolic citizenship in Saudi Arabia. In the medical context, some AI diagnostic systems have been treated as “employees” of a hospital for liability purposes. Currently, in most jurisdictions, including China, surgical robots are regulated as Class III medical devices—high-risk products. This unequivocally places them in the legal category of “object” or “product.” This classification simplifies liability into existing channels: product liability against the manufacturer or medical malpractice liability against the surgeon/hospital. However, this traditional framing is increasingly strained. When a medical robot errs in suturing based on its own visual processing, as reported in a fatal UK case, or causes unexplained tissue damage, solely blaming the surgeon for lack of experience or the hospital for systemic failure feels incomplete. It neglects the causative contribution of the machine’s autonomous function.

Empirical analysis of litigation reveals a concerning trend: the neglect of product liability claims in favor of medical malpractice claims. A review of cases involving robotic surgery shows that plaintiffs almost exclusively allege errors in surgical planning, inadequate surgeon training, or lack of informed consent. Claims directly targeting a design or defect in the medical robot itself are exceedingly rare, even when injuries are atypical or causation is unclear. This occurs because: (a) the robot is still viewed as a tool under the surgeon’s ultimate control; (b) the lines between product failure and medical error are inherently blurred in device-intensive surgery; (c) forensic expertise is often geared towards evaluating clinical care, not reverse-engineering AI software; and (d) there is a procedural and psychological bias towards holding the tangible, human-led hospital accountable rather than pursuing a complex product liability case against a remote manufacturer. This neglect is unsustainable. As autonomy increases, the machine’s role as a causative agent will become undeniable. The legal system must develop a framework that can adequately address the unique product liability dimensions of intelligent medical robot systems.

Toward a Dynamic Legal and Liability Framework

Addressing these challenges requires a nuanced, multi-pronged approach that evolves with the technology.

1. A Phased Approach to Legal Status: A binary, static classification is inadequate. The law must adopt a dynamic, phased model that reflects the medical robot‘s operational autonomy.

- Current Phase (Object Status): For contemporary teleoperated and semi-autonomous systems, retaining their status as advanced medical devices/products is pragmatically and legally sound. The surgeon is the primary decision-maker, and the machine is an instrument. Liability should flow through established tort doctrines, albeit with heightened standards.

- Future Phase (Limited Legal Personhood): When fully autonomous medical robot systems performing complex procedures become clinically viable, the “object” model will fracture. At this point, conferring a limited legal personhood—a legal fiction—becomes a necessary tool to rationalize liability. This would not grant human rights but would treat the AI as a distinct legal entity for the specific purpose of bearing responsibility. It could own a fund for liability (funded by manufacturers, operators, and insurers), be directly “sued,” and have its “actions” scrutinized. This elegantly resolves the problem of attributing acts arising from its independent intelligence without anthropomorphizing it. The responsibility would then be allocated to its creators, operators, and trainers under principles similar to vicarious liability or principles for controlling legal persons.

2. Expanding the Circle of Liable Parties: The Critical Role of the Designers. Product liability law traditionally targets manufacturers and sellers. For AI-driven medical robot systems, this is insufficient. The “defect” often originates in the design phase: in the algorithms, the architecture of neural networks, the training data sets, or the human-robot interaction protocols. When the designer is a separate entity from the manufacturer, the injured patient currently cannot sue the designer directly; the manufacturer must seek indemnity later. This obscures accountability and shields a key responsible party. The law must be amended to include designers as primary, direct defendants in medical robot product liability suits. This imposes a powerful duty of care at the very source of the system’s intelligence, incentivizing safety-by-design and rigorous validation of AI behavior.

3. Establishing Clear Standards for “Design Defect” in AI. Proving a design defect in an AI medical robot is the paramount challenge. The defect is not a cracked gear but a flawed logic, a biased dataset, or an unsafe reward function in reinforcement learning. Courts need coherent, technology-informed tests. We can adapt established U.S. legal doctrines into a composite test for an “unreasonably dangerous” AI design:

| Test | Legal Question | Application to Medical Robot AI |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer Expectation Test | Was the product less safe than an ordinary consumer would expect? | Would a reasonable patient expect a surgical robot to make certain types of uncommanded movements or misinterpret anatomical structures? |

| Risk-Utility Test | Do the foreseeable risks of the design outweigh its benefits? | Does the benefit of an autonomous suturing module’s speed outweigh the risk of its occasional misidentification of tissue layers? This requires quantifying both. A simplified model could be: $$ R_u = \frac{\sum (p_i \cdot s_i)}{B} $$ where $R_u$ is the risk-utility ratio, $p_i$ is the probability of harm $i$, $s_i$ is its severity, and $B$ is the aggregate medical benefit. A design is defective if $R_u > \alpha$, where $\alpha$ is a legally/socially determined threshold. |

| Reasonable Alternative Design (RAD) Test | Could a practical, safer alternative design have been adopted? | Could the neural network have been trained on more diverse data to avoid a failure mode? Could a “trapped key” software architecture have prevented the unsafe state? Expert testimony on AI safety becomes crucial here. |

Establishing specialized forensic units capable of performing these assessments—auditing AI code, training data, and system logs—is essential for providing courts with the necessary evidence.

4. Integrating Liability Frameworks: A Proposed Synthesis. The liability regime for a medical robot incident must be flexible, capable of applying different rules based on the nature of the failure. The following integrated model is proposed:

Let $L$ represent total liability. It can be a function of contributions from different parties based on the failure mode $F$.

- For Pure Product Defects (hardware/manufacturing): $$ L = L_{manufacturer} $$ Strict liability applies.

- For Design & Algorithmic Defects: $$ L = L_{designer} + L_{manufacturer} $$ Joint and several liability applies. The Risk-Utility and RAD tests are key.

- For Operational Errors (Surgeon/Hospital): $$ L = L_{hospital} $$ Medical malpractice principles apply.

- For Hybrid Failures (AI error compounded by human error): $$ L = \alpha L_{designer/manufacturer} + \beta L_{hospital} $$ where $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are apportionment factors determined by causation analysis. This is the most complex and likely scenario.

- For Autonomous AI Actions (Future Scenario): $$ L = Fund_{Robot}(+ L_{creator} \text{ if negligent creation/training}) $$ The limited legal person (the medical robot) is primarily liable through its fund, with recourse against its creators for fundamental faults in its “upbringing.”

The advent of intelligent medical robot systems exposes a growing rift between technological capability and legal doctrine. Clinging to the simple “product” classification for increasingly autonomous machines risks creating accountability gaps and injustice for injured patients. Conversely, prematurely granting full legal personhood is philosophically fraught and practically unnecessary. The prudent path is a phased, functional approach. Currently, we must strengthen the existing framework by explicitly bringing designers into the scope of product liability and developing sophisticated, AI-literate standards for proving design defects. As technology crosses the threshold into meaningful surgical autonomy, the creation of a limited legal personhood for advanced medical robot systems will become a logical and necessary step to ensure a coherent, just, and efficient liability regime. This proactive evolution of tort law is not merely an academic exercise; it is a fundamental prerequisite for building the trust required to fully realize the life-saving potential of robotic surgery, ensuring that innovation proceeds with responsibility at its core.