In this study, we focus on the thermal behavior of a hollow planetary roller screw, a critical component in linear actuation systems for aerospace, machine tools, and medical devices. The planetary roller screw is renowned for its high thrust capacity, speed, and longevity, but during operation, friction at the thread meshing interfaces and bearing rotations generates significant heat. This heat leads to temperature rise and thermal deformation, which can degrade positioning accuracy, reduce load-bearing capability, and even cause system failure. To mitigate these issues, hollow designs are employed, allowing coolant circulation through the central bore to dissipate heat. Our objective is to investigate the thermal deformation of such a hollow planetary roller screw under various cooling conditions, using finite element analysis. We calculate thermal boundary conditions based on two primary heat sources: thread meshing friction and bearing rotation friction. Then, we establish an equivalent thermal model to simulate temperature distributions and thermal deformations under no cooling, water cooling, and oil cooling scenarios. Furthermore, we explore the effects of coolant flow rate and screw rotational speed on thermal deformation in oil-cooled cases. The findings aim to guide cooling strategy selection, temperature control, and thermal error prediction for hollow planetary roller screw systems.

The planetary roller screw operates by converting rotary motion into linear motion through rolling contact between the screw, rollers, and nut. This mechanism minimizes friction compared to sliding contacts, but at high speeds or under heavy loads, the cumulative friction heat becomes substantial. The hollow planetary roller screw incorporates an axial bore through the screw shaft, enabling internal coolant flow to enhance heat dissipation. This design expands its applicability in high-temperature environments. However, the thermal dynamics are complex due to multiple heat sources and transient heat transfer processes. We approach this by first deriving analytical expressions for heat generation rates and convection coefficients, then implementing these in a finite element framework. Our analysis considers material properties, structural parameters, and operational conditions to provide a comprehensive understanding of thermal performance.

We begin by simplifying the planetary roller screw assembly for thermal modeling. The screw’s threaded section is approximated as a cylinder with a diameter equal to the pitch diameter, reducing computational complexity while retaining essential thermal characteristics. The nut assembly (including rollers) and support bearings are treated as constant heat sources, with their heat fluxes applied to the screw shaft at contact areas. We assume that the ambient temperature remains constant at 20°C, and convection coefficients for air and coolant are constant and independent of temperature variations. These assumptions facilitate a tractable model without sacrificing accuracy for comparative studies.

The primary heat sources in a planetary roller screw are the thread meshing friction between the screw, rollers, and nut, and the rotational friction in the support bearings. For the thread meshing, the heat generation rate per unit time, \( H_n \), is given by:

$$ H_n = 0.12 \pi n M_T $$

where \( n \) is the rotational speed of the planetary roller screw in revolutions per minute (rpm), and \( M_T \) is the total frictional torque of the screw pair. This torque comprises components due to material elastic hysteresis \( M_m \), roller spin sliding \( M_r \), and lubricant viscosity \( M_l \). Thus, the total frictional torque on the screw side \( M_{TS} \) and nut side \( M_{TN} \) are:

$$ M_{TS} = M_{ms} + M_{rs} + M_{ls} $$

$$ M_{TN} = M_{mn} + M_{rn} + M_{ln} $$

The overall screw pair torque is \( M_T = M_{TS} + M_{TN} \). Based on prior research, approximately 43% of the heat generated in the planetary roller screw nut assembly is conducted to the screw shaft. Therefore, the heat flux density at the screw-nut contact area, \( q_n \), is:

$$ q_n = \frac{0.43 H_n}{A_n} $$

where \( A_n \) is the surface area of contact between the screw shaft and the nut assembly.

For the bearing friction, the heat generation rate \( H_b \) is calculated as:

$$ H_b = \frac{M_b n_b}{9550} $$

Here, \( n_b \) is the bearing rotational speed (often equal to the screw speed in many configurations), and \( M_b \) is the bearing frictional torque, which sums the load-dependent torque \( M_p \) and lubricant viscous torque \( M_0 \):

$$ M_b = M_p + M_0 $$

The viscous torque depends on the bearing type and lubrication. For a bearing with average diameter \( d_m \), when the kinematic viscosity \( \nu \) and speed product \( \nu n_b \geq 2000 \),

$$ M_0 = 10^{-7} f_0 (\nu n_b)^{2/3} d_m^3 $$

and when \( \nu n_b < 2000 \),

$$ M_0 = 160 \times 10^{-7} f_0 d_m^3 $$

The load-dependent torque is \( M_p = f_1 N_p d_m \), where \( f_1 \) is a coefficient related to bearing type and load, and \( N_p \) is the bearing load. The heat flux density at the screw-bearing contact area, \( q_b \), is similarly derived as \( q_b = \frac{0.43 H_b}{A_b} \), with \( A_b \) being the contact surface area.

Next, we consider heat exchange with the environment. The screw shaft convects heat to the surrounding air, characterized by the convection coefficient \( h \). Using the Nusselt number correlation for a rotating cylinder, we have:

$$ h = \frac{\lambda Nu}{L} $$

where \( \lambda \) is the thermal conductivity of air, \( L \) is the characteristic length (taken as the screw pitch diameter \( d_s \)), and \( Nu \) is the Nusselt number given by:

$$ Nu = 0.133 Re^{2/3} Pr^{1/3} $$

The Reynolds number \( Re = \omega d_s^2 / \nu \), with \( \omega \) as the angular velocity of the screw, and \( Pr \) is the Prandtl number for air.

For the hollow planetary roller screw, internal coolant flow through the bore provides forced convection cooling. The convection coefficient \( h_m \) for the coolant depends on the flow regime. For turbulent flow (typical in cooling applications), the Nusselt number is:

$$ Nu_f = 0.023 Re_f^{0.8} Pr_f^{0.4} $$

where \( Re_f = \frac{\rho v d_0}{\mu} \) is the Reynolds number for the coolant flow, with \( \rho \) as density, \( v \) as flow velocity, \( d_0 \) as the bore diameter, and \( \mu \) as dynamic viscosity. \( Pr_f \) is the Prandtl number for the coolant. Then,

$$ h_m = \frac{\lambda_f}{d_0} Nu_f $$

These equations form the basis for our thermal boundary conditions. We compile material and structural parameters for a representative hollow planetary roller screw, as shown in Tables 1 and 2. Using these, we compute thermal parameters for various operational scenarios, summarized in Table 3.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Density (kg/m³) | 7810 |

| Specific Heat at 20°C (J/(kg·°C)) | 552.66 |

| Thermal Conductivity at 20°C (W/(m·°C)) | 36.92 |

| Linear Expansion Coefficient at 20°C (10⁻⁶/°C) | 11.8 |

| Elastic Modulus at 20°C (GPa) | 212 |

| Poisson’s Ratio | 0.29 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Bore Diameter (mm) | 7 |

| Bearing Section Length (mm) | 22 |

| Bearing Section Diameter (mm) | 17 |

| Thread Section Diameter (mm) | 15 |

| Nut Travel Length (mm) | 80 |

| Condition | \( q_n \) (W/m²) | \( q_b \) (W/m²) | \( h \) (W/(m²·K)) | \( h_m \) (W/(m²·K)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No cooling, screw speed 600 rpm | 4778 | 4482 | 20 | N/A |

| Water cooling, screw speed 600 rpm, flow rate 9.2 L/min | 4778 | 4482 | 20 | 4944 |

| Oil cooling (R134a), screw speed 600 rpm, flow rate 2.3 L/min | 4778 | 4482 | 20 | 1245 |

| Oil cooling (R134a), screw speed 600 rpm, flow rate 9.2 L/min | 4778 | 4482 | 20 | 3765 |

| Oil cooling (R134a), screw speed 600 rpm, flow rate 18.4 L/min | 4778 | 4482 | 20 | 6568 |

| Oil cooling (R134a), screw speed 600 rpm, flow rate 23 L/min | 4778 | 4482 | 20 | 7854 |

| Oil cooling (R134a), screw speed 300 rpm, flow rate 18.4 L/min | 2279 | 2223 | 12.3 | 6568 |

| Oil cooling (R134a), screw speed 1200 rpm, flow rate 18.4 L/min | 9556 | 8964 | 31 | 6568 |

With these parameters, we proceed to finite element modeling. We use ANSYS software to create a thermal analysis model of the hollow planetary roller screw shaft. The model employs SOLID70 elements, which are 3-D thermal solid elements suitable for transient heat transfer analysis. The mesh consists of 23,652 elements and 5,848 nodes, ensuring sufficient resolution for accurate temperature predictions. The screw shaft is modeled as a cylindrical geometry with the bore, and the nut and bearing heat sources are applied as moving and stationary thermal loads, respectively.

To simulate the reciprocating motion of the nut along the screw, we implement an APDL (ANSYS Parametric Design Language) script that moves the heat flux \( q_n \) along the screw surface in steps corresponding to the screw lead. At each load step, the nut contact area is updated, and after the nut passes, the convection coefficient \( h \) is applied to that region to account for air cooling. This approach captures the transient thermal interaction between the moving nut and the screw. The bearing heat flux \( q_b \) is applied statically at the bearing mounting locations. External convection \( h \) is applied to all outer surfaces except at nut and bearing contact areas, and internal forced convection \( h_m \) is applied to the bore surface and coolant inlet holes. The analysis runs until thermal equilibrium is reached, defined as when temperature changes become negligible over time.

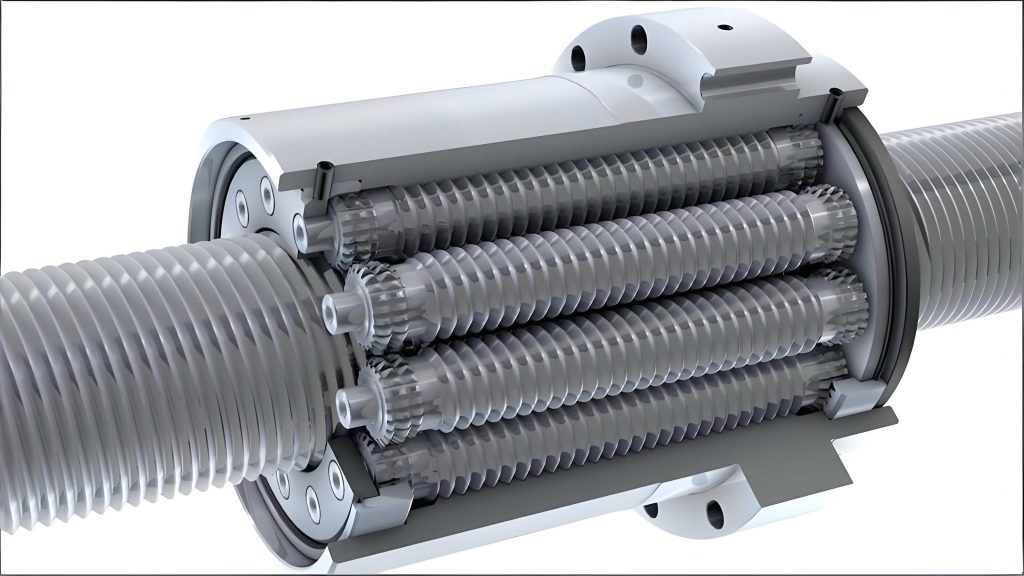

The image above illustrates a typical planetary roller screw assembly, highlighting the intricate interaction between the screw, rollers, and nut. In our hollow design, the central bore is visible, allowing coolant passage to manage thermal loads. This visual context aids in understanding the geometric complexity addressed in our finite element model.

We first examine temperature distributions under three cooling scenarios: no cooling, water cooling, and oil cooling, all at a screw rotational speed of 600 rpm. For water and oil cooling, the coolant flow rate is set to 9.2 L/min. The simulation runs until the nut completes 32 reciprocating cycles along the 80 mm travel length, taking 51.2 seconds. Figure 1 shows the temperature contour on the screw shaft at 51.2 seconds for the no-cooling case. The maximum temperature reaches 28.456°C, corresponding to a temperature rise of 8.456°C above the ambient 20°C. The heat accumulates steadily over time without active cooling, leading to continuous temperature increase.

In contrast, with water cooling, the maximum temperature drops to 22.5375°C at 51.2 seconds, as shown in Figure 2. This represents a temperature rise of only 2.5375°C, demonstrating the effectiveness of water as a coolant. For oil cooling using R134a refrigerant oil, the maximum temperature is 22.9268°C (rise of 2.9268°C), slightly higher than water cooling but still significantly lower than the no-cooling case. Thus, water cooling outperforms oil cooling in terms of heat dissipation, likely due to water’s higher specific heat and thermal conductivity. However, oil is often preferred in mechanical systems to prevent corrosion and provide lubrication benefits. In all three scenarios, the hottest spots occur at the bearing mounting locations, indicating that bearing friction is a dominant heat source. This is consistent with the higher heat flux densities \( q_b \) compared to \( q_n \) in Table 3. The temperature evolution at the bearing point over time is plotted in Figure 3, revealing that with cooling, temperatures stabilize quickly, whereas without cooling, they rise monotonically.

To quantify thermal deformation, we conduct coupled thermal-structural analyses. After obtaining the temperature field, we apply it as a thermal load to a structural model of the screw shaft, using the same mesh but with structural elements like SOLID185. The material properties from Table 1, including the thermal expansion coefficient, are used to compute displacements due to thermal strain. The screw is constrained at the bearing locations to simulate realistic mounting, and the resulting deformations are evaluated. For the no-cooling case at 600 rpm, the total thermal deformation (vector sum of displacements) peaks at 2.90 μm, with an axial deformation (along the screw axis) of 2.57 μm. Under water cooling, these values reduce to 1.52 μm (total) and 1.52 μm (axial). With oil cooling at 9.2 L/min, deformations are 1.52 μm (total) and 1.52 μm (axial), similar to water cooling due to comparable temperature rises. The deformation patterns show that maximum displacements occur near the free end of the screw shaft, away from constraints, as expected from thermal expansion effects.

Next, we investigate the influence of coolant flow rate on thermal behavior for the oil-cooled planetary roller screw at 600 rpm. We test flow rates of 2.3 L/min, 9.2 L/min, 18.4 L/min, and 23 L/min. The temperature rise at the bearing point over time is plotted in Figure 4. As flow rate increases, the steady-state temperature rise decreases markedly. For instance, at 2.3 L/min, the temperature rise stabilizes around 5.2°C, whereas at 23 L/min, it drops to about 1.8°C. This is because higher flow rates enhance the forced convection coefficient \( h_m \), improving heat removal from the bore surface. The time to reach thermal equilibrium also shortens with increased flow. Table 4 summarizes the thermal deformations for these flow rates.

| Flow Rate (L/min) | Total Deformation (μm) | Axial Deformation (μm) |

|---|---|---|

| 2.3 | 2.90 | 2.57 |

| 9.2 | 1.52 | 1.52 |

| 18.4 | 0.805 | 0.796 |

| 23 | 0.727 | 0.683 |

The data indicate that increasing flow rate from 2.3 to 18.4 L/min reduces total deformation by 72%, from 2.90 μm to 0.805 μm. However, further increasing to 23 L/min yields only a minor improvement to 0.727 μm, suggesting diminishing returns. Thus, an optimal flow rate exists beyond which additional cooling provides limited benefits. For this planetary roller screw, 18.4 L/min appears adequate for effective thermal management. Figure 5 displays the total deformation contour for the 18.4 L/min case, with a maximum of 0.805 μm at the free end.

We also study the effect of screw rotational speed on thermal deformation, keeping the oil coolant flow rate constant at 18.4 L/min. Speeds of 300 rpm, 600 rpm, and 1200 rpm are analyzed. The heat generation rates \( H_n \) and \( H_b \) are proportional to speed, as per Equations (1) and (6), so higher speeds lead to greater heat input. Figure 6 shows the bearing point temperature rise over time for these speeds. At 300 rpm, the temperature rise stabilizes at approximately 1.5°C after 32.4 seconds; at 600 rpm, it reaches 2.8°C after 51.2 seconds; and at 1200 rpm, it climbs to 5.6°C after a longer period. The higher slopes of the temperature curves indicate faster heat accumulation at increased speeds. Table 5 lists the corresponding thermal deformations.

| Screw Speed (rpm) | Total Deformation (μm) | Axial Deformation (μm) |

|---|---|---|

| 300 | 0.443 | 0.337 |

| 600 | 0.805 | 0.796 |

| 1200 | 1.60 | 1.60 |

As speed doubles from 300 to 600 rpm, total deformation increases by 82%, and from 600 to 1200 rpm, it doubles again. This near-linear relationship underscores the critical impact of operational speed on thermal performance. The axial deformation follows a similar trend, emphasizing that thermal expansion along the screw axis is a primary concern for positioning accuracy. Figure 7 illustrates the deformation contour for the 300 rpm case, with a maximum of 0.443 μm.

To delve deeper, we analyze the heat transfer mechanisms mathematically. The overall energy balance for the hollow planetary roller screw can be expressed as:

$$ \rho c_p \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + \dot{q}_{gen} – \dot{q}_{conv} $$

where \( \rho \) is density, \( c_p \) is specific heat, \( T \) is temperature, \( t \) is time, \( k \) is thermal conductivity, \( \dot{q}_{gen} \) is internal heat generation rate per volume from friction, and \( \dot{q}_{conv} \) is convective heat loss per volume. For the screw shaft, \( \dot{q}_{gen} \) is zero except at surface contacts where heat fluxes \( q_n \) and \( q_b \) are applied as boundary conditions. The convective term includes both external air convection and internal coolant convection. Solving this equation numerically via finite element method yields the transient temperature fields we observed.

Moreover, the thermal deformation \( \delta \) can be estimated from the temperature distribution using the linear thermal expansion formula:

$$ \delta = \alpha L_0 \Delta T $$

where \( \alpha \) is the coefficient of thermal expansion, \( L_0 \) is the original length, and \( \Delta T \) is the temperature change. For complex geometries like the planetary roller screw, this simplifies to integrated strain over the volume. Our finite element approach computes deformations directly from thermal strains, providing precise results.

In discussion, we note that the bearing regions consistently exhibit the highest temperatures, highlighting the need for focused cooling or enhanced bearing designs in planetary roller screw systems. Water cooling’s superiority over oil cooling stems from its higher heat capacity and conductivity, but practical considerations like corrosion prevention may favor oil. The flow rate analysis suggests that beyond a certain point, increasing coolant flow yields minimal gains, so system designers should balance cooling performance with pump power and cost. The strong dependence on screw speed implies that for high-speed applications, active cooling is essential to maintain accuracy. Our model assumptions, such as constant convection coefficients, could be refined by incorporating temperature-dependent properties for more accurate predictions in extreme conditions.

In conclusion, our study on the hollow planetary roller screw provides insights into thermal deformation under various cooling strategies. We developed a comprehensive thermal model based on friction heat calculations and finite element analysis. Results show that water cooling is more effective than oil cooling, but both significantly reduce temperatures compared to no cooling. The bearing areas are critical hotspots. Increasing coolant flow rate diminishes thermal deformation, but with diminishing returns at higher flows. Screw rotational speed has a proportional effect on temperature rise and deformation. These findings can inform the selection of cooling methods, optimization of flow parameters, and thermal error compensation in planetary roller screw systems. Future work could explore advanced cooling techniques, such as phase-change materials or hybrid cooling, and validate results with experimental measurements on actual hollow planetary roller screw assemblies.