In the realm of agricultural robotics, the end effector stands as a pivotal component, directly influencing harvesting efficiency and fruit quality. As we delve into the challenges of citrus picking in hilly regions, it becomes evident that the design and application of end effectors are critical for advancing agricultural mechanization. This article explores the principles, influencing factors, and future directions of end effectors for citrus harvesting, drawing from extensive research and practical considerations. We aim to provide a comprehensive analysis that underscores the importance of innovative end effector designs in overcoming the unique obstacles presented by丘陵地形.

The cultivation of citrus fruits in hilly areas is a significant economic activity, yet harvesting remains largely manual, accounting for approximately 40% of total production time. This labor-intensive process is fraught with inefficiencies and risks of fruit damage. With aging populations and urbanization reducing rural labor forces, the need for mechanized solutions is urgent. However, most existing harvesting robots are experimental and ill-suited for the complex terrains of hilly orchards. A key reason for this shortfall lies in the limitations of current end effectors, which often lack universality and cause skin injuries. Thus, rethinking end effector design is essential for practical implementation.

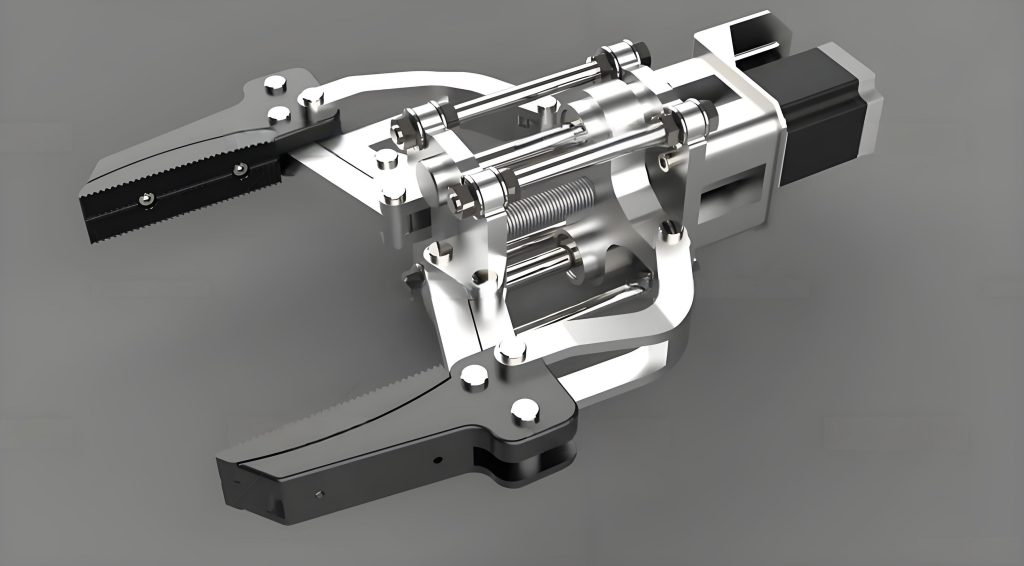

The primary function of an end effector is to emulate human fingers, separating fruit from stem without harming the peel. Over the years, various end effector designs have emerged, predominantly based on two principles: mimicking human five-finger movements and simulating biological swallowing actions. The former includes multi-fingered grippers, while the latter involves suction-based mechanisms. Additionally, stem separation techniques can be categorized into physical methods (e.g., scissors, rotating blades) and thermal methods (e.g., electric heating wires, laser cutting). Each approach has its merits and drawbacks, which we analyze in detail below.

To better understand the landscape of end effector designs, we summarize key types in Table 1, focusing on their principles, advantages, and challenges in hilly orchard contexts.

| Type of End Effector | Principle | Advantages | Challenges in Hilly Orchards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-fingered Gripper | Simulates human finger movements for grasping and cutting | Adaptable to fruit sizes, precise control | Susceptible to leaf obstruction, requires specific fruit orientation |

| Suction-based End Effector | Mimics biological swallowing using suction cups | Efficient stem cutting, reduces movement time | Prone to clogging from leaves, fruit damage during collection |

| Rotary Blade End Effector | Employs rotating blades for stem severance | High cutting speed, minimal force required | Risk of damaging nearby fruits, alignment issues |

| Hybrid End Effector | Combines grasping and suction elements | Versatile, reduces fruit slippage | Complex design, increased weight and size |

The effectiveness of an end effector is governed by several mechanical and environmental factors. From a theoretical perspective, the grasping force must balance between secure hold and avoiding damage. This can be modeled using the equation for frictional force: $$F_f = \mu \cdot N$$ where \(F_f\) is the frictional force preventing slippage, \(\mu\) is the coefficient of friction between the end effector material and citrus peel, and \(N\) is the normal force applied by the gripper. Excessive \(N\) can cause bruising, while insufficient \(N\) leads to dropped fruits. Optimizing this relationship is crucial for end effector performance.

Furthermore, the torque required for stem cutting can be expressed as: $$\tau = F \cdot r \cdot \sin(\theta)$$ where \(\tau\) is the cutting torque, \(F\) is the applied force, \(r\) is the blade radius, and \(\theta\) is the angle of attack. This highlights the importance of blade design and positioning in end effector mechanisms. In hilly orchards, where fruits may be at odd angles, adaptive cutting systems are necessary.

The challenges facing end effector deployment in hilly regions are multifaceted, encompassing both external and internal factors. Externally, terrain irregularities limit robot mobility, sunlight variations affect machine vision, and citrus growth patterns (e.g., clustering, leaf occlusion) complicate picking. Internally, end effector design aspects such as shape, size, material, and integration of grasping and cutting functions play pivotal roles. We elaborate on these factors below, with a focus on their impact on end effector efficacy.

Regarding external factors, hilly terrain introduces slopes and uneven ground, necessitating compact and portable harvesting robots. The end effector must operate within a constrained workspace, as robot arms may have limited reach. Sunlight intensity and direction change throughout the day, interfering with visual recognition systems that guide the end effector. This can be quantified by the signal-to-noise ratio in image processing: $$SNR = \frac{P_{signal}}{P_{noise}}$$ where \(P_{signal}\) represents the useful image data for fruit detection, and \(P_{noise}\) includes glare and shadows. Low SNR leads to misidentification, causing end effector misalignment.

Citrus growth habits further exacerbate difficulties. Fruits often grow in clusters or are hidden by leaves, requiring the end effector to navigate dense foliage. The stem strength varies, with typical tensile strengths ranging from 5 to 20 MPa, depending on variety and ripeness. The end effector must apply precise cutting forces to avoid tearing the peel. Additionally, fruit size dispersion (e.g., diameters from 50 to 100 mm) demands adaptable grasping mechanisms.

Internal factors revolve around end effector design specifics. The grasping structure should conform to citrus morphology, using flexible materials to distribute pressure evenly. The overall dimensions must be minimized for maneuverability, yet large enough to accommodate fruit variability. Force feedback systems are essential for real-time adjustment; we can model the control loop as: $$u(t) = K_p \cdot e(t) + K_i \int e(t) dt + K_d \frac{de(t)}{dt}$$ where \(u(t)\) is the control signal to the end effector actuators, \(e(t)\) is the error between desired and actual grasp force, and \(K_p\), \(K_i\), \(K_d\) are PID gains. Proper tuning ensures gentle but firm handling.

Integration of grasping and cutting actions is another critical aspect. Ideally, a single power source should drive both functions to reduce weight and complexity. The kinematic chain can be analyzed using transformation matrices: $$T = \prod_{i=1}^{n} A_i$$ where \(A_i\) represents the homogeneous transformation for each joint, and \(T\) defines the end effector position and orientation. Streamlining this chain enhances speed and reliability.

To address these challenges, we propose several solutions centered on end effector innovation. First, modular and portable designs can facilitate robot transport in hilly areas. The end effector should be detachable, with quick-connect interfaces for easy maintenance. Second, algorithm optimization for machine vision can mitigate sunlight effects; techniques like histogram equalization or deep learning-based segmentation improve robustness. The accuracy can be measured by: $$\text{Precision} = \frac{TP}{TP + FP}$$ where \(TP\) is true positives (correct fruit detections) and \(FP\) is false positives. High precision ensures efficient end effector targeting.

Third, material selection is paramount. Combining flexible polymers for contact surfaces with lightweight alloys for structural parts can achieve both compliance and durability. The stress-strain relationship for flexible materials follows: $$\sigma = E \cdot \epsilon$$ where \(\sigma\) is stress, \(E\) is Young’s modulus, and \(\epsilon\) is strain. Lower \(E\) values allow for greater deformation without damaging fruit. Additionally, scientific pruning of trees can simplify the end effector’s task by reducing foliage density and fruit clustering.

Looking ahead, the future of end effectors for citrus picking lies in advanced material science, miniaturization, and intelligent control. We envision end effectors that seamlessly blend柔性材料 with rigid components, offering adaptive grasping surfaces that mimic human skin. Weight reduction through composite materials will enhance agility, allowing end effectors to reach inner tree canopies. Single-power-source designs that unify grasping and cutting motions will simplify mechanics, as represented by the efficiency equation: $$\eta = \frac{P_{out}}{P_{in}}$$ where \(\eta\) is efficiency, \(P_{out}\) is useful mechanical power for harvesting, and \(P_{in}\) is input power. Maximizing \(\eta\) reduces energy consumption and extends operational time.

Moreover, sensor fusion will play a key role. Integrating tactile, force, and visual sensors into the end effector enables real-time feedback for delicate handling. The data fusion can be modeled using Bayesian inference: $$P(A|B) = \frac{P(B|A) P(A)}{P(B)}$$ where \(P(A|B)\) is the posterior probability of successful grasp given sensor readings \(B\). This enhances decision-making for the end effector.

In conclusion, the development of effective end effectors for citrus picking in hilly orchards requires a holistic approach that considers mechanical design, environmental factors, and technological integration. By addressing the outlined challenges through innovative solutions, we can pave the way for practical harvesting robots. The end effector remains the cornerstone of this endeavor, and continued research into its optimization will undoubtedly yield significant advancements in agricultural automation. As we refine these systems, the dream of efficient, damage-free citrus harvesting in challenging terrains will become a reality, bolstering economic sustainability and food security.