In my exploration of aging societies, I have observed that the integration of companion robots into elderly households presents a promising solution for addressing loneliness and caregiving challenges. As a researcher deeply involved in this field, I conducted a longitudinal study to understand how older adults interact with these intelligent devices over time. This article, written from my first-person perspective as an observer, delves into the dynamic process of companion robot usage among the elderly, drawing from experimental observations spanning nine months. The term “companion robot” will be frequently mentioned to emphasize its role in smart elderly care, and I will employ tables and formulas to systematically summarize key findings and models.

The rapid aging of populations worldwide has heightened the need for innovative care solutions, and companion robots have emerged as a potential tool to provide companionship and support. My study was motivated by the gap in understanding long-term usage patterns, as most prior research focused on short-term interactions or laboratory settings. I aimed to capture the natural evolution of how elderly individuals adopt, adapt to, and sometimes abandon companion robots in their daily lives. Throughout this journey, I witnessed firsthand the complexities of human-robot relationships, which I will detail in the following sections.

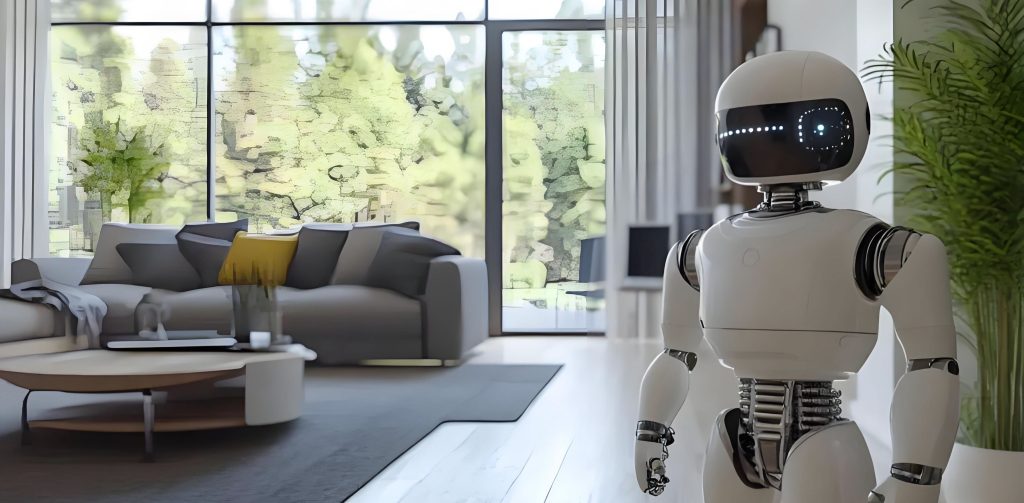

To ground my work, I reviewed existing literature on social robots and elderly users. Previous studies often examined pre-usage attitudes or short-term encounters, but few explored extended domestic use. For instance, some research highlighted that elderly individuals prefer companion robots with warm appearances, while others noted phases like “appropriation,” “integration,” and “transformation” during month-long deployments. However, these studies typically involved non-specialized devices like voice assistants, whereas my focus was on a dedicated companion robot designed for elderly needs. This robot, referred to as “W” in my study, features a humanoid form, voice interaction, and tailored functions such as one-touch calls and family communication. My investigation sought to extend these insights by mapping the entire usage lifecycle, from initial contact to potential disuse.

In designing my study, I adopted an experimental observation approach, placing the companion robot in 47 elderly households across three regions for nine months. I selected participants through snowball sampling, ensuring diversity in age, gender, and family structure. The sample included 47 elderly individuals, aged 56 to 83, with a balanced gender distribution and varied educational backgrounds. Below is a table summarizing the demographic characteristics of the participants, which I compiled to contextualize the findings.

| Characteristic | Category | Number of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 21 |

| Female | 26 | |

| Region | Fujian | 19 |

| Henan | 18 | |

| Shandong | 10 | |

| Age (years) | 56-60 | 15 |

| 61-65 | 14 | |

| 66-70 | 4 | |

| 71-75 | 5 | |

| 76-80 | 5 | |

| 81-85 | 4 | |

| Family Structure | Living Alone | 1 |

| Couple Only | 19 | |

| Nuclear Family | 13 | |

| Extended Family | 14 | |

| Education Level | University | 21 |

| High School/Vocational | 13 | |

| Middle School | 10 | |

| Primary School or Below | 3 |

I conducted semi-structured interviews at four stages: upon introduction, after three months, six months, and at the end of nine months. Each interview lasted approximately 90 minutes, and I recorded and transcribed the conversations to analyze usage behaviors and perceptions. Additionally, I provided notebooks for participants to log their daily interactions with the companion robot, though only five maintained consistent records. The companion robot itself was a compact humanoid device, about 25 cm tall, with flexible joints, LED facial expressions, and functionalities like dancing, voice communication, and health monitoring. Its design aimed to foster emotional connection, which I believed would influence long-term engagement.

From my observations, the usage of the companion robot unfolded in a dynamic, non-linear process that I categorize into four phases: initial contact, active use, intermittent discontinuation, and abandonment. Each phase exhibited distinct behaviors and attitudes, which I will describe in detail, supported by tables and formulas to encapsulate patterns. The term “companion robot” is central here, as its role evolved from a novelty to a potential tool or even a companion.

During the initial contact phase, elderly individuals displayed diverse reactions upon first encountering the companion robot. I noted three primary behaviors: eager exploration, patient learning, and passive use. For example, 20 participants, predominantly female, immediately engaged with the device, touching it, asking questions, and even naming it. This aligns with media equation theory, where humans tend to treat media with social cues as real actors. I formulated this initial engagement level \( E_i \) as a function of perceived warmth \( W \) and competence \( C \) of the companion robot:

$$ E_i = \alpha W + \beta C + \epsilon $$

where \( \alpha \) and \( \beta \) are coefficients reflecting the influence of warmth and competence, and \( \epsilon \) represents individual differences. In contrast, 14 participants adopted a cautious approach, observing demonstrations before trying, while 13 showed reluctance due to fears of complexity or privacy concerns. This variability underscored the importance of tailored onboarding processes for companion robots in elderly care.

The active use phase typically lasted one to three months, during which participants enthusiastically explored the companion robot’s functions. Usage frequency peaked, with many engaging multiple times daily for activities like information retrieval, entertainment, and casual conversation. I recorded an average usage time of 30 minutes per session, often integrated into daily routines such as after meals. To model this phase, I defined usage intensity \( I_a(t) \) at time \( t \) as:

$$ I_a(t) = \gamma e^{-\lambda t} + \delta $$

where \( \gamma \) represents initial curiosity, \( \lambda \) is the decay rate due to novelty wearing off, and \( \delta \) is a baseline usage level. This exponential decay model captures the gradual decline in engagement after the peak. Participants often placed the companion robot in visible areas like living rooms, and some even customized it with accessories, indicating a sense of ownership. Social sharing was common, with many showing the device to friends or posting about it online, which enhanced their social capital. The table below summarizes the key behaviors during active use, based on my interviews.

| Behavior Type | Description | Percentage of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Information Access | Using weather, news, or time functions | 60% |

| Entertainment | Playing music, dancing, or watching actions | 75% |

| Companionship Interaction | Engaging in casual dialogue with the robot | 50% |

| Social Sharing | Demonstrating the robot to family or friends | 85% |

| Personalization | Modifying appearance or functions | 30% |

As time progressed, I observed a shift to intermittent discontinuation, where usage became sporadic. This phase, occurring between one to six months, involved participants using the companion robot less frequently—perhaps once every week or two—but for longer durations, such as during household chores. The functionality narrowed mostly to entertainment, as practical features were deemed inferior to smartphones. I conceptualized this intermittent behavior as a stochastic process, where the probability of use \( P_u(t) \) at time \( t \) follows a Poisson distribution with a decreasing rate parameter \( \mu(t) \):

$$ P_u(t) = \frac{\mu(t)^k e^{-\mu(t)}}{k!} $$

with \( \mu(t) = \mu_0 e^{-\kappa t} \), where \( \mu_0 \) is the initial rate, \( \kappa \) is the decline constant, and \( k \) represents usage events. Factors contributing to this decline included limited functionality, connectivity issues, and privacy worries. For instance, many participants expressed that the companion robot could not engage in deep conversations, reducing its perceived value as a true companion. The table below outlines the main reasons for intermittent discontinuation, derived from my analysis.

| Reason Category | Specific Issues | Impact Level (High/Medium/Low) |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Limitations | Inability to handle complex queries or chores | High |

| Technical Problems | Unstable internet connection or battery drain | Medium |

| Privacy Concerns | Fears of data collection or surveillance | Medium |

| Loss of Novelty | Decreased interest over time | High |

| Social Saturation | Reduced sharing opportunities with peers | Low |

By the six-month mark, most participants entered the abandonment phase, where the companion robot was largely unused but often kept as a decorative item or stored away. Interestingly, even when not actively used, many expressed attachment, hesitating to return the device at the study’s end. This paradoxical behavior highlights the dual role of companion robots as both tools and emotional objects. I represent the abandonment decision \( A \) as a function of self-efficacy \( S \), social support \( F \), and robot functionality \( R \):

$$ A = \theta_1 S + \theta_2 F + \theta_3 R + \eta $$

where \( \theta_1, \theta_2, \theta_3 \) are weights, and \( \eta \) accounts for unobserved factors. Lower self-efficacy and limited social support often predicted earlier abandonment, while higher functionality delayed it. The companion robot’s presence, though passive, served as a symbol of technological integration, fostering a sense of connection to modern society.

Throughout this dynamic process, I identified two critical influencing factors: self-efficacy and social support. Self-efficacy, or individuals’ belief in their ability to use the companion robot, significantly shaped usage patterns. Participants with prior smartphone experience tended to maintain longer active use, translating skills to the new device. I modeled this relationship as:

$$ U(t) = \sigma S(t) + \tau $$

where \( U(t) \) is usage level at time \( t \), \( S(t) \) is self-efficacy, and \( \sigma, \tau \) are parameters. As challenges arose, such as complex features, self-efficacy dropped, leading to discontinuation. Social support, particularly from friends and community, played a reinforcing role. Peer interactions about the companion robot provided motivation, whereas family members’ over-involvement sometimes reduced elderly individuals’ autonomy, causing frustration. This aligns with social support theory, where middle-layer networks (friends) offer positive reinforcement, while inner-layer (family) support can be double-edged. The formula below integrates these factors into a comprehensive usage model:

$$ \frac{dU}{dt} = \rho S(t) + \phi F(t) – \psi D(t) $$

where \( \frac{dU}{dt} \) is the rate of change in usage, \( \rho \) and \( \phi \) are coefficients for self-efficacy \( S(t) \) and social support \( F(t) \), and \( \psi D(t) \) represents decay due to discontinuation factors \( D(t) \) like functionality gaps.

In reflecting on these findings, I see that companion robots occupy a hybrid space between tool and companion for the elderly. Initially, they are perceived as novel gadgets, but over time, their utility as information sources or entertainment devices becomes primary. However, the emotional bond, though shallow, persists through symbolic presence. This has implications for designing companion robots for smart elderly care: they should balance functional simplicity with emotional engagement, accommodate intermittent use patterns, and foster social connections without undermining user autonomy. My study underscores the need for longitudinal approaches in human-robot interaction research, as short-term observations miss these evolving dynamics.

To conclude, the journey of companion robots in elderly households is marked by a dynamic, non-linear usage process encompassing eager adoption, active exploration, sporadic use, and eventual disuse. From my first-person perspective as a researcher, I have learned that elderly individuals are not passive recipients but active agents who adapt technology to their lives, even if incompletely. The companion robot, while not a perfect substitute for human companionship, offers a bridge to digital inclusion and emotional solace. Future work should refine models like those I proposed, incorporating cultural and individual variabilities to enhance the effectiveness of companion robots in aging societies. As I continue this research, I remain hopeful that these insights will pave the way for more empathetic and sustainable smart elderly care solutions.