The evolution of power transmission systems towards higher load capacity, speed, and precision has established the Planetary Roller Screw (PRS) mechanism as a pivotal component in modern actuation systems. Its unique design, featuring multi-point and multi-pair thread engagement, offers significant advantages in load-bearing capability. However, this very characteristic, combined with operation under high-speed and heavy-load conditions, leads to substantial internal frictional heat generation. This accumulation of heat elevates the internal temperature of the planetary roller screw assembly, inducing thermal deformation, degrading lubrication performance, accelerating wear, and ultimately causing thermal error that compromises positioning and transmission accuracy. In severe cases, it can lead to premature mechanism failure. This review synthesizes current research on the thermal characteristics of planetary roller screw mechanisms. Beginning with an analysis of their structural composition and the underlying mechanisms of thermal phenomena, we systematically examine five critical areas: heat source analysis, methodologies for thermal characteristic analysis, temperature rise and thermo-mechanical coupling, thermal deformation, and thermal error alongside optimization strategies. By summarizing existing knowledge and identifying gaps, this article aims to provide a foundational reference for future research aimed at enhancing the thermal management and operational reliability of planetary roller screw systems.

Introduction and Operating Principle

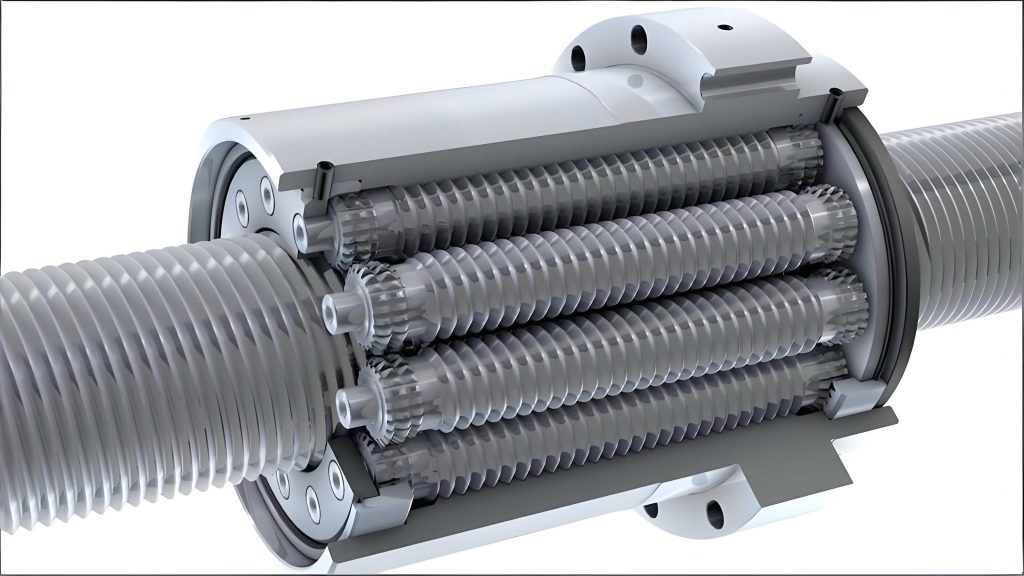

A Planetary Roller Screw (PRS) mechanism is a high-precision mechanical actuator that converts rotary motion into linear motion (or vice-versa) through the combined action of threaded meshing and gear meshing. Primarily implemented as the standard-type PRS, the system comprises several key components as illustrated. The central screw features a multi-start thread and is typically the rotating element. Surrounding the screw are several planet rollers, each with a single-start thread that meshes with the screw’s threads. The rollers are retained and evenly spaced by a cage or retainer. Their ends are geared and engage with an internal ring gear (nut or stationary ring) to prevent skewing and ensure parallelism with the screw axis. The nut, also with a multi-start thread, meshes with the rollers and acts as the translating component in most configurations.

The dominant thermal issue stems from frictional losses at multiple contact interfaces during operation: the screw-roller and nut-roller thread contacts, roller end journal-bearing cage contacts, and support bearing contacts. This generated heat, if not adequately dissipated, raises the component temperatures. The thermal characteristics mechanism can be summarized as follows: frictional work generates heat, leading to a non-uniform temperature field. This causes differential thermal expansion among the components (thermal deformation), altering the precise geometric relationships essential for accuracy, resulting in thermal error. Concurrently, elevated temperatures degrade lubricant properties, increasing the risk of wear and reducing operational reliability. Both effects can culminate in a loss of system precision and potential failure.

Analysis of Heat Generation and Transfer

In the context of planetary roller screw analysis, heat transfer via radiation is typically negligible compared to conduction and convection. The primary heat sources within a PRS-driven system are multifaceted.

Primary Frictional Heat Sources:

- Thread Contact Interfaces: Friction at the screw-roller and nut-roller meshing threads is the predominant source.

- Roller End Contacts: Friction between the roller journals and the cage pockets.

- Support Bearings: Friction within the support bearings at the screw ends.

Ancillary System Heat: The driving servo motor contributes significant heat from copper losses, core losses (hysteresis, eddy currents), and windage losses. This heat conducts into the connected screw.

Heat transfer occurs through conduction between solid components (e.g., from contact interfaces to the screw body, nut, and housing) and convection from component surfaces to the ambient air or coolant. Forced convection is present on rotating parts like the screw and nut exterior, while natural convection often occurs on stationary housings.

| Heat Source | Location | Primary Transfer Mode (Initial) | Ultimate Dissipation Path |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screw-Roller Thread Friction | Thread flanks | Conduction to screw & roller bodies | Convection from screw/nut surface; Conduction to housing |

| Nut-Roller Thread Friction | Thread flanks | Conduction to nut & roller bodies | Convection from nut surface; Conduction to housing |

| Roller End – Cage Friction | Roller journals / Cage pockets | Conduction to roller ends & cage | Convection from cage/housing; Oil mist/ splash |

| Support Bearing Friction | Bearing races & rolling elements | Conduction to screw shaft & housing | Convection from housing/bearing exterior |

| Motor Losses | Motor stator/rotor | Conduction through motor mount to screw | Convection from motor casing; Cooling system |

Methodologies for Thermal Characteristic Analysis

Investigating the thermal behavior of planetary roller screw mechanisms relies on a combination of numerical simulation and experimental validation, grounded in heat transfer theory.

Numerical Simulation Methods

Finite Element Analysis (FEA): Due to the complexity of the planetary roller screw geometry, model simplification is necessary. Typically, non-engaged thread sections and small fillets are removed. Exploiting symmetry and assuming equal load sharing among rollers, a sector model (1/N of the full assembly, where N is the number of rollers) is often analyzed to reduce computational cost. Key steps include:

- Calculating friction torque and deriving thermal boundary conditions (heat flux, convective heat transfer coefficients).

- Importing the simplified geometry into FEA software, defining material properties.

- Meshing, with refinement at contact regions.

- Applying thermal and structural loads for steady-state, transient, or coupled thermo-mechanical analysis.

This approach effectively predicts temperature fields and thermal deformations, including transient effects from moving heat sources along the screw.

Thermal Network Method (TNM): This finite-difference-based approach discretizes the system into temperature nodes connected by thermal resistances (conductive, convective, contact). The network is solved using energy balance equations.

$$Q_{gen,i} + \sum_{j} \frac{T_j – T_i}{R_{ij}} = C_i \frac{dT_i}{dt}$$

where \( Q_{gen,i} \) is the heat generated at node i, \( T_i \) and \( T_j \) are nodal temperatures, \( R_{ij} \) is the thermal resistance between nodes i and j, and \( C_i \) is the thermal capacitance of node i. The TNM is computationally efficient for system-level transient and steady-state temperature prediction, though its accuracy depends heavily on the subjective selection of node locations and the estimation of thermal resistances.

| Method | Advantages | Limitations / Challenges | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Finite Element Analysis (FEA) | High spatial resolution of temperature/stress fields; Can model complex geometry and moving heat sources; Enables detailed thermo-mechanical coupling. | High computational cost; Requires significant model simplification; Contact definition can be complex. | Detailed analysis of component temperatures, localized stress, and deformation. |

| Thermal Network Method (TNM) | Computationally fast; Suitable for system-level and transient analysis; Easily modified for parametric studies. | Lower spatial resolution; Accuracy depends on node selection and resistance estimation; Difficult to capture complex 3D heat flow. | Rapid prediction of system warm-up, average component temperatures, and design sensitivity studies. |

Experimental Research Methods

Experimental validation is crucial. It involves instrumenting a planetary roller screw test rig with temperature sensors (thermocouples, infrared thermography) to measure temperature evolution under controlled loads, speeds, and cooling conditions. Experiments validate numerical models, provide real-world data on warm-up times and steady-state temperatures, and quantify thermal deformations (e.g., using displacement probes). Key challenges include limited spatial measurement coverage and the difficulty of isolating single effects in a coupled system. Therefore, experiments and simulations are complementary: experiments provide validation data, while simulations offer full-field, time-domain insights that are impractical to measure.

Temperature Rise, Thermo-Mechanical Coupling, and Deformation

The non-uniform temperature field induces differential thermal expansion. Thermo-mechanical coupling analysis, often treated as a one-way sequential coupling, first computes the temperature field and then applies it as a thermal load in a structural analysis to determine deformation and stress.

Quantifying Heat Generation

The heat generation rate \( \dot{Q} \) (W) from a friction source is directly related to the friction torque \( M_f \) (N·m) and rotational speed \( n \) (rpm):

$$\dot{Q} = \frac{2\pi}{60} M_f n \approx 1.047 \times 10^{-4} M_f n$$

1. Bearing Friction Torque & Heat: The total bearing friction torque \( M_{f, bearing} \) includes load-dependent \( M_1 \) and viscous \( M_v \) terms.

$$ M_{f, bearing} = M_1 + M_v $$

$$ M_1 = f_1 F_\beta d_m $$

where \( f_1 \) is a factor depending on bearing design and load, \( F_\beta \) is the equivalent bearing load, and \( d_m \) is the bearing mean diameter.

$$ M_v =

\begin{cases}

10^{-7} f_0 (\nu_0 n)^{2/3} d_m^3 & \text{if } \nu_0 n \ge 2000 \\

160 \times 10^{-7} f_0 d_m^3 & \text{if } \nu_0 n < 2000

\end{cases} $$

where \( f_0 \) depends on bearing type and lubrication, and \( \nu_0 \) is the kinematic viscosity of the lubricant.

2. Planetary Roller Screw Friction Torque & Heat: The total PRS friction torque \( M_{PRS} \) is a sum of components from differential sliding \( M_C \), roller spin \( M_S \), roller-cage friction \( M_{RC} \), lubricant viscous drag \( M_E \), and, for preloaded assemblies, preload \( M_{PR} \).

For a preloaded planetary roller screw:

$$ M_{PRS} = M_C + M_S + M_{RC} + M_E + M_{PR} $$

The associated heat generation is \( \dot{Q}_{PRS} = 1.047 \times 10^{-4} M_{PRS} n \).

3. Motor Heat: Heat from motor inefficiencies: \( \dot{Q}_{motor} = (1 – \eta) \frac{2\pi}{60} T_{out} n \), where \( \eta \) is the motor efficiency and \( T_{out} \) is the output torque.

Thermal Deformation

The axial thermal elongation of the screw, often the most critical deformation, is given by:

$$ \Delta L = \alpha \Delta T L $$

where \( \alpha \) is the coefficient of thermal expansion, \( \Delta T \) is the average temperature rise of the screw, and \( L \) is the effective threaded length. This elongation directly translates to a positioning error (thermal error) in the nut’s travel.

Coupled thermo-mechanical models reveal that temperature rise not only causes bulk expansion but also alters contact conditions. Thermal gradients can change clearances and preload, redistributing the load among the rollers and threads, which in turn affects localized heat generation—a classic coupled problem. Most current research focuses on ambient conditions; studying the effects of dynamic external thermal environments and their interaction with internal friction remains an important area for future planetary roller screw research.

Thermal Error and Mitigation Strategies

Thermal error, responsible for a significant portion (40-70%) of total error in precision systems, is a critical performance metric for planetary roller screw mechanisms. Mitigation follows two principle approaches: error prevention (hardware-based) and error compensation (software-based).

Error Prevention (Thermal Management)

This strategy focuses on minimizing heat generation and enhancing heat removal at the design stage.

- Structural Design: Optimizing thread profile, using materials with low thermal expansion or high conductivity, and designing efficient heat paths.

- Cooling Systems:

- Natural Convection: Adequate finning and surface area for low-duty cycles.

- Forced Air Cooling: Using fans or air nozzles directed at the nut/screw.

- Liquid Cooling: Employing a hollow screw with internal coolant circulation for high-heat flux scenarios. Coolant flows through a central tube and returns via the annulus, effectively extracting heat from the core.

- Lubrication: Selecting high-temperature, thermally stable greases or implementing oil-air or oil-jet lubrication to improve heat removal from contacts and maintain lubricant film strength.

Error Compensation

This involves predicting the thermal error in real-time and applying a corrective offset through the control system. The process flow is: data acquisition (temperature and error measurements) -> model training (using algorithms on historical data) -> real-time prediction -> compensation signal application.

Accurate, robust thermal error models are essential. While extensively studied for ball screws (using techniques like neural networks, regression models), application to planetary roller screw mechanisms is less common. Models must correlate temperature measurements (often from key points on the nut, housing, or screw ends) with the resulting positional error of the nut.

| Strategy Category | Specific Methods | Key Principle | Considerations for Planetary Roller Screw |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error Prevention (Hardware) | Optimized thread profile/material | Reduce friction coefficient or improve heat conduction. | Must maintain meshing conditions and load capacity. |

| Forced air / Liquid cooling | Actively remove heat from the system. | Coolant channel design in hollow screws; sealing for liquid systems. | |

| Advanced lubrication systems | Reduce friction and carry away heat. | Grease selection for high temp; complexity of oil-air systems for multiple rollers. | |

| Error Compensation (Software) | Model-based compensation (e.g., thermal network, FEM) | Predict error from physics-based models using measured or estimated temperatures. | Model complexity and requirement for accurate boundary conditions. |

| Data-driven compensation (e.g., neural networks, regression) | Learn the mapping between temperature sensors and error from experimental data. | Requires extensive training data; robustness to varying operational conditions. |

Optimization of Thermal Performance

Research on optimizing planetary roller screw thermal performance is nascent. Insights can be drawn from related fields like gear systems and ball screws. Optimization can target multiple aspects:

- Geometry and Material: Multi-objective optimization of thread parameters and material selection to balance stiffness, strength, and thermal growth.

- Cooling Design: Optimizing coolant flow rate, channel geometry, and nozzle placement using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and response surface methodology.

- System Control: Optimizing motion profiles to minimize heat generation while meeting performance requirements.

- Error Model Accuracy: Applying optimization algorithms (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization, Genetic Algorithms) to tune the parameters of data-driven thermal error prediction models for higher accuracy.

Future work should integrate these optimization approaches specifically for the multi-roller, multi-contact nature of the planetary roller screw mechanism.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

The thermal characteristics of planetary roller screw mechanisms present a significant challenge for their application in high-performance, precision systems. This review has outlined the fundamental mechanisms, analysis methods, and current understanding of heat generation, temperature rise, thermo-mechanical coupling, deformation, and error mitigation. While foundational work has been established, several critical avenues warrant further investigation to advance the thermal management of planetary roller screw systems:

- Advanced Coupled Modeling: Developing high-fidelity models that integrate thermo-mechanical-fluidal (e.g., lubricant flow) coupling under realistic conditions, including extreme temperatures, dynamic external thermal environments, and varying lubrication regimes. The interaction between thermal effects, load distribution, and wear is particularly complex and needs integrated modeling approaches.

- High-Fidelity Simulation: Creating more geometrically accurate finite element models that reduce simplification assumptions while remaining computationally tractable, potentially through advanced sub-modeling or multi-scale techniques.

- Innovative Thermal Management Design: Exploring novel cooling architectures beyond simple hollow screws, advanced thermal interface materials, and phase-change cooling concepts tailored to the planetary roller screw geometry.

- Robust Thermal Error Prediction and Compensation: Developing and validating application-specific thermal error models and compensation strategies for planetary roller screw mechanisms, leveraging both physics-based and advanced data-driven techniques like machine learning.

- System-Level Optimization: Implementing holistic design optimization frameworks that simultaneously consider thermal, structural, and dynamic performance of the planetary roller screw within the complete actuation system.

Addressing these research directions will be pivotal in enhancing the reliability, accuracy, and lifespan of planetary roller screw mechanisms, solidifying their role in the next generation of high-performance electromechanical actuation systems.