As an observer and researcher in the field of artificial intelligence, I find myself increasingly concerned with the legal ramifications of intelligent robots. These entities, characterized by autonomy, learning capabilities, and adaptability, are no longer mere tools in human hands. Instead, they operate independently, making decisions that can lead to harm, thereby challenging traditional frameworks of civil liability. In this article, I will explore these challenges, examine recent regulatory efforts, and propose potential solutions for assigning liability for damages caused by intelligent robots, with a focus on autonomous vehicles and other smart machines. I will incorporate tables and formulas to summarize key points and models, ensuring a comprehensive analysis.

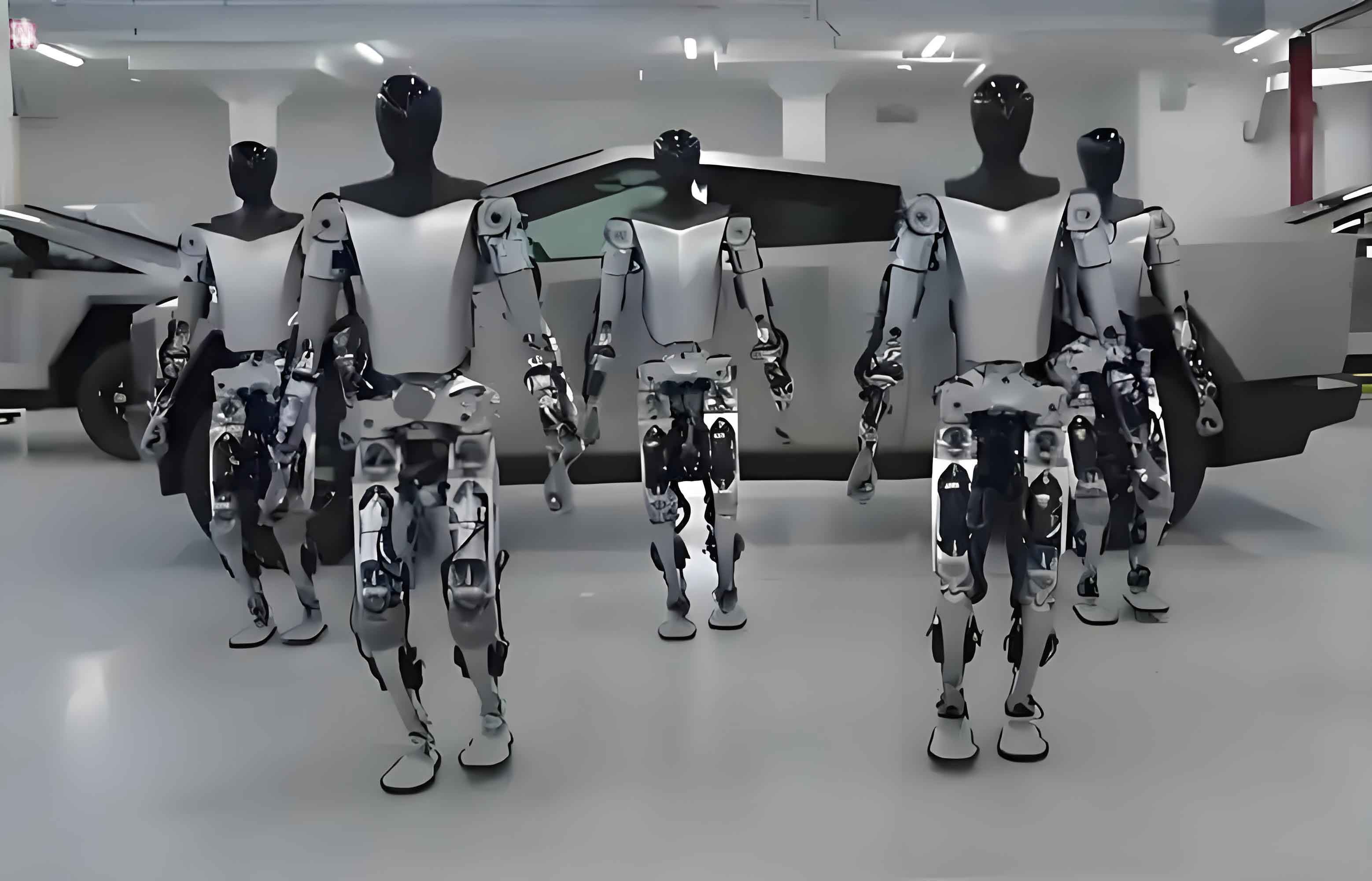

The rise of intelligent robots marks a paradigm shift in technology. Unlike conventional machines, which follow pre-programmed instructions, intelligent robots possess the ability to learn from experience, interact with their environment, and adjust their actions autonomously. This autonomy is defined as the capacity to make and execute decisions without external control, while learning capabilities allow them to evolve beyond their initial programming. As a result, intelligent robots such as autonomous cars, medical robots, and caregiving robots are becoming integral to society. However, their unique features—such as unpredictability, interpretability issues, and complex causality—create gaps in existing liability rules. When an intelligent robot causes personal injury or property damage, determining who should be held responsible becomes a legal conundrum. Traditional tort law and product liability frameworks, designed around human actors or static products, may prove inadequate. For instance, in cases involving fully autonomous intelligent robots, it may be impossible to attribute fault to a human operator or prove a product defect, leaving victims uncompensated. This article aims to delve into these issues, using structured analyses via tables and mathematical models to clarify the path forward.

To understand the liability challenges posed by intelligent robots, we must first define their core characteristics. I propose the following table summarizing key traits that differentiate intelligent robots from traditional machines:

| Characteristic | Description | Impact on Liability |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | Ability to make independent decisions without human intervention, based on sensor data and environmental interactions. | Reduces direct human control, complicating fault attribution in tort law. |

| Learning Capacity | Capability to learn from experiences and adapt behavior over time, often using machine learning algorithms. | Introduces unpredictability, making it hard to foresee actions and prove defects. |

| Physical Embodiment | Existence in a tangible form, such as a car or robot body, enabling interaction with the physical world. | Facilitates direct causation of harm, necessitating liability rules for physical damages. |

| Adaptability | Adjustment of actions based on changing environments, leading to unique decisions in novel situations. | Creates interpretability challenges, as decisions may not be traceable to original programming. |

These characteristics collectively undermine traditional liability frameworks. Let’s consider the formula for establishing liability in tort law: $$L = F \times C$$, where \(L\) represents liability, \(F\) denotes fault (or breach of duty), and \(C\) signifies causation. For intelligent robots, both \(F\) and \(C\) become problematic. Fault may not be assignable to a human, and causation can be obscured by the robot’s autonomous learning. For example, if an autonomous vehicle causes an accident, the human “driver” might be a passive passenger, eliminating fault. Similarly, product liability relies on proving a defect, but with intelligent robots, defects may arise from unpredictable learning processes rather than manufacturing errors. This can be expressed as: $$D = D_d + D_l$$, where \(D\) is the total damage, \(D_d\) is damage from design/manufacturing defects, and \(D_l\) is damage from learning-induced behaviors. Isolating \(D_l\) is often impossible, leading to liability gaps.

The inadequacy of traditional liability rules is evident in several areas. First, negligence-based tort law requires a human actor to have breached a duty of care. With intelligent robots operating independently, no such human exists. For instance, in a Level 4 or 5 autonomous vehicle, the human is merely a passenger, and the car’s actions are governed by its AI system. Courts have historically allowed leeway for human limitations, but intelligent robots are expected to perform with mechanical precision. This shifts the standard of care from human reasonableness to machine performance benchmarks. Second, product liability, as a strict liability regime, demands proof of defect, harm, and causation. However, the autonomous nature of intelligent robots makes defects elusive. Consider a scenario where an intelligent robot causes harm due to a decision made after learning from unforeseen data. The manufacturer might argue that the harm was unforeseeable, invoking the “state-of-the-art” defense. This can be modeled using probability theory: let \(P_d\) be the probability of a defect, and \(P_u\) be the probability of unforeseeable harm from learning. The overall liability risk \(R\) becomes: $$R = P_d \cdot D_d + P_u \cdot D_u$$, where \(D_d\) and \(D_u\) are respective damages. As \(P_u\) increases with robot autonomy, traditional product liability becomes less effective.

Third, vicarious liability, which holds employers responsible for employees’ actions, might analogously apply to intelligent robots deployed by companies. But this requires defining the “scope of employment” for an intelligent robot, which is ambiguous. If an intelligent robot delivers goods and causes harm, is it acting within its programmed duties? This uncertainty necessitates new rules. To illustrate, I propose a table comparing traditional liability approaches and their limitations with intelligent robots:

| Liability Framework | Key Requirement | Challenge with Intelligent Robots | Example Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negligence (Tort Law) | Breach of duty of care by a human actor. | No human in control; duty shifts to robot performance. | Autonomous car accident with no driver intervention. |

| Product Liability | Proof of defect in product design/manufacturing. | Defects may arise from autonomous learning, not initial design. | Medical robot error due to adaptive algorithm changes. |

| Vicarious Liability | Employee acting within scope of employment. | Defining scope for intelligent robots is complex and untested. | Delivery drone causing property damage during route. |

In response to these challenges, regulatory bodies like the European Union have begun exploring new liability regimes. The EU Parliament’s Legal Affairs Committee has proposed several innovations, emphasizing that intelligent robots’ autonomy makes them more than simple tools. Their recommendations include a strict liability scheme, mandatory insurance, compensation funds, and even considering legal personality for advanced intelligent robots. From my perspective, these proposals aim to balance victim compensation with innovation promotion. For instance, strict liability would hold manufacturers or users liable regardless of fault, simplifying claims for victims. This can be expressed as: $$L_s = C$$, where \(L_s\) is strict liability and \(C\) is causation alone. The EU also suggests differential liability based on regulatory approval: if an intelligent robot meets safety standards, liability might be limited, otherwise, full strict liability applies. This introduces a regulatory variable \(R_a\) (approval status), modifying liability: $$L_d = f(R_a, C)$$, where \(L_d\) is differential liability.

Building on these ideas, I propose several potential schemes for intelligent robot civil liability. Each scheme has merits and drawbacks, which I summarize in a comparative table below:

| Scheme | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages | Mathematical Representation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strict Liability | Manufacturer or user liable for all damages caused by intelligent robot, based solely on causation. | Ensures victim compensation; reduces litigation costs by avoiding defect proof. | May stifle innovation if liability is too burdensome; risk of over-compensation. | $$L_{strict} = \sum D_i \text{ for all damages } D_i \text{ caused}$$ |

| Differential Liability | Liability varies based on regulatory approval: limited for approved intelligent robots, strict otherwise. | Encourages safety compliance; balances innovation and protection. | Requires robust regulatory framework; may create loopholes if approval is voluntary. | $$L_{diff} = \begin{cases} \alpha \cdot D & \text{if approved} \\ D & \text{if not approved} \end{cases}$$ where \(\alpha < 1\). |

| Mandatory Insurance & Compensation Fund | Manufacturers or owners must insure intelligent robots; a fund covers uncovered damages. | Spread risk across industry; guarantees victim recovery. | Adds costs; fund management complexity; may not cover all damage types. | $$I + F \geq D$$, with \(I\) as insurance payout and \(F\) as fund contribution. |

| Legal Personality for Intelligent Robots | Grant advanced intelligent robots legal status as “electronic persons,” liable for their own actions. | Directly addresses autonomy; simplifies attribution of responsibility. | Controversial; requires new legal categories; may obscure human accountability. | $$L_{robot} = f(\text{robot assets})$$, assuming robot holds rights and obligations. |

To delve deeper, let’s consider formulas for allocating liability in these schemes. For strict liability, the total compensation \(C_t\) from manufacturer to victim can be modeled as: $$C_t = \int_{0}^{T} d(t) \, dt$$, where \(d(t)\) is the damage function over time \(T\), assuming continuous harm. This ensures full recovery but may need caps. For differential liability, if an intelligent robot is approved by a regulatory agency, liability could be limited to a multiple of its market value \(V\). For example: $$L_{approved} = \min(D, k \cdot V)$$, where \(k\) is a constant (e.g., 2). This incentivizes safety while protecting manufacturers. For insurance models, the premium \(P\) can be calculated based on risk assessment: $$P = \beta \cdot E[D]$$, where \(\beta\) is a factor accounting for administrative costs and profit, and \(E[D]\) is the expected damage from the intelligent robot. This spreads risk but requires accurate damage estimation.

The learning capacity of intelligent robots adds another layer of complexity. Machine learning algorithms often operate as “black boxes,” making decisions inexplicable even to designers. This interpretability problem affects causality proofs. We can model this using information theory: let \(I\) be the information required to explain a robot’s decision, and \(H\) be the available information. The explicability gap \(G\) is: $$G = I – H$$. When \(G > 0\), liability attribution fails. To mitigate this, some propose transparency mandates, but these may conflict with intellectual property rights. Alternatively, liability could be assigned based on risk creation: if deploying an intelligent robot increases societal risk \(R_s\), the deployer should bear liability proportional to \(R_s\). This can be expressed as: $$L_{risk} = \gamma \cdot \Delta R_s$$, where \(\gamma\) is a liability factor and \(\Delta R_s\) is the incremental risk from the intelligent robot.

In the context of autonomous vehicles, a key example of intelligent robots, these issues are particularly acute. Governments like the U.S. and Germany are developing policies, such as requiring black boxes to record decisions. This enhances explicability but doesn’t solve liability wholly. From my view, a hybrid approach combining strict liability with insurance might be optimal. For instance, a no-fault insurance system for autonomous vehicles, where victims claim from insurers regardless of fault, and insurers subrogate against manufacturers if defects are proven. This balances efficiency and justice. Mathematically, let \(I_v\) be insurance payout to victim, and \(R_m\) be manufacturer responsibility. Then: $$I_v = D$$, and $$R_m = I_v – I_p$$ if defect proven, where \(I_p\) is insurer’s subrogation recovery. This ensures swift compensation while preserving accountability.

Looking ahead, the evolution of intelligent robots will demand continuous legal adaptation. As autonomy increases, we may see more incidents where no human or manufacturer is directly culpable. This could lead to calls for granting legal personality to intelligent robots, akin to corporate personhood. However, this raises ethical questions about responsibility and rights. From a liability perspective, if an intelligent robot has legal personality, it could own assets to pay damages, and its “guardians” (e.g., manufacturers) might have residual liability. This creates a layered model: $$L_{total} = L_{robot} + L_{guardian}$$, where \(L_{robot}\) is limited to robot’s assets, and \(L_{guardian}\) covers shortfalls. Such models require careful calibration to avoid moral hazard.

In conclusion, the civil liability of intelligent robots is a pressing issue that transcends traditional legal boundaries. Through this analysis, I have highlighted how autonomy and learning capabilities create unpredictability, interpretability, and causality gaps. Tables and formulas have helped summarize these challenges and potential solutions. Whether through strict liability, differential schemes, insurance, or legal personality, the goal is to balance innovation incentives with victim protection. As intelligent robots become ubiquitous, legislators and courts must engage in comprehensive论证 to develop rules that ensure justice and foster technological progress. The journey ahead will require interdisciplinary collaboration, drawing on law, ethics, and computer science to craft liability frameworks as dynamic as the intelligent robots themselves.

To further illustrate the liability allocation, consider a decision tree model for intelligent robot accidents. Let \(A\) be the accident event, \(M\) be manufacturer action, \(U\) be user action, and \(R\) be robot autonomous decision. The probability of liability \(P(L)\) can be modeled as: $$P(L) = P(A) \cdot [P(M) \cdot L_m + P(U) \cdot L_u + P(R) \cdot L_r]$$, where \(L_m, L_u, L_r\) are liability assignments to manufacturer, user, and robot respectively. As \(P(R)\) grows with robot autonomy, \(L_r\) must be defined. This underscores the need for clear rules. Ultimately, the future of intelligent robot liability lies in adaptive regulations that evolve alongside the technology, ensuring that as these machines learn and adapt, so too does our legal system.