In the realm of precision mechanical transmissions, the development of efficient and compact gear systems has always been a focal point. As an engineer specializing in gear design and computer-aided engineering, I have extensively researched and worked on enhancing transmission technologies. One innovative approach that has captured my attention is the integration of traditional strain wave gear principles with oscillating tooth mechanisms. This hybrid system, which I refer to as an end-face strain wave gear transmission with oscillating teeth, aims to overcome inherent limitations in conventional designs. By merging the advantages of strain wave gear drives and oscillating tooth drives, this new configuration fundamentally resolves the conflict between flexible wheel deformation and load-bearing capacity typical in standard strain wave gear systems. Additionally, it mitigates issues such as large radial dimensions and non-adjustable meshing gaps found in oscillating tooth drives. The result is a transmission that retains the benefits of both while increasing the number of simultaneously meshing teeth and enlarging the gear module, thereby significantly boosting power transmission capabilities and extending service life. The successful development of this reducer holds promise for broad applications in robotics, aerospace, and industrial machinery.

The core innovation lies in the unique meshing mechanism. Traditional strain wave gear systems rely on the elastic deformation of a flexspline to generate motion, which can limit durability under high loads. In contrast, the end-face strain wave gear with oscillating teeth employs a rigid configuration where oscillating teeth engage with an end-face gear profile, enabling more robust power transfer. This design not only enhances efficiency but also allows for finer adjustments and greater precision. Throughout this article, I will delve into the principles, digital modeling, and dynamic simulation of this system, emphasizing the role of strain wave gear concepts in its operation. Key aspects include motion theory, parametric design, virtual assembly, and kinematic analysis using advanced software tools like Pro/ENGINEER. By leveraging computational methods, I have validated the theoretical foundations and optimized the design for practical implementation.

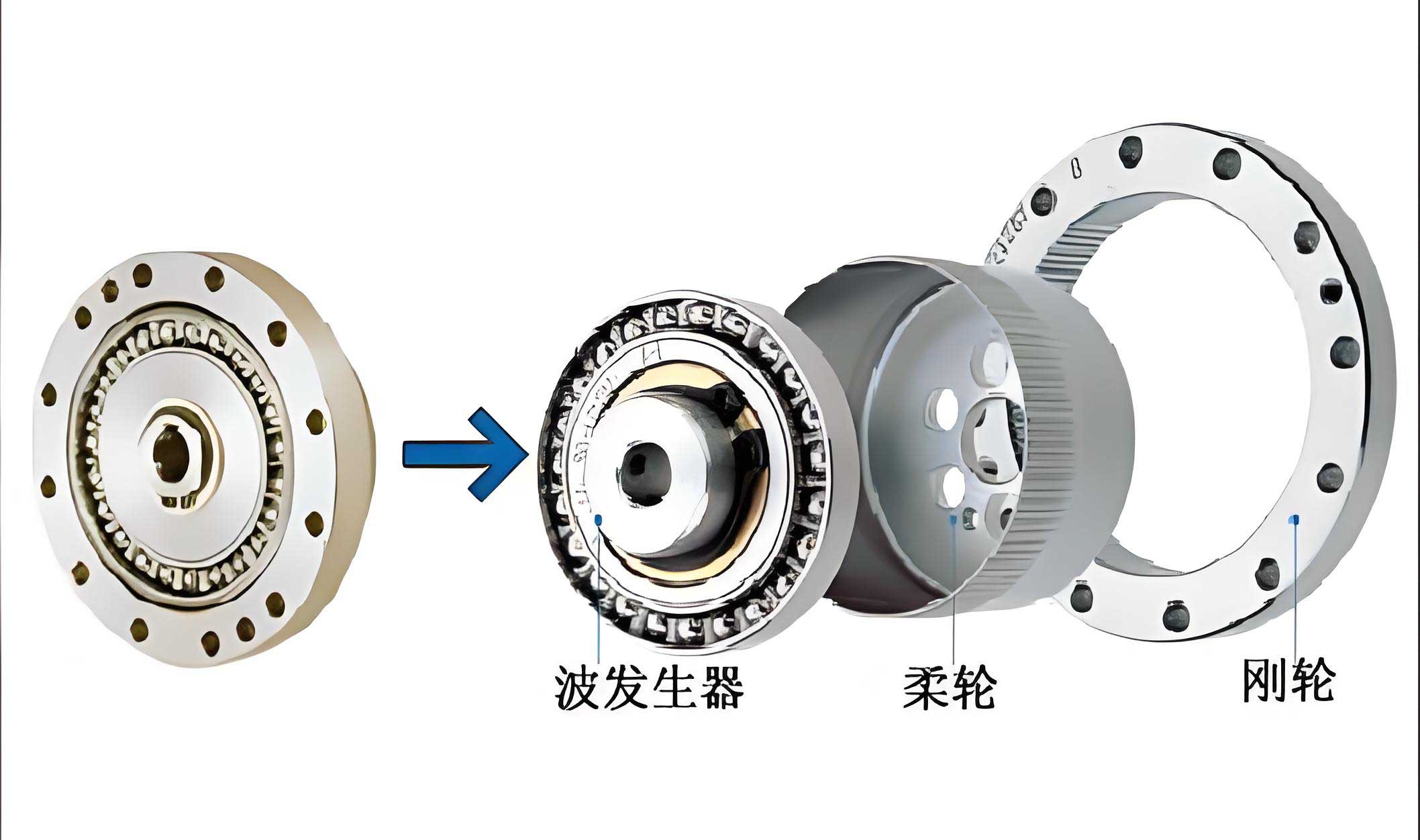

To understand the mechanics, let’s start with the motion principle. The end-face strain wave gear transmission with oscillating teeth consists of several key components: an end-face gear, a wave generator (which functions as an end-face harmonic gear), oscillating teeth, and a slotted wheel. The system operates as follows: when the input shaft rotates, it drives the wave generator attached to it. The wave generator, typically a multi-lobed cam, actuates the oscillating teeth housed in slots on the slotted wheel. These teeth move axially and engage with the stationary end-face gear fixed to the housing. This engagement causes the slotted wheel to rotate, and since the slotted wheel is connected to the output shaft via a torque tube, motion and power are transmitted to the output. The transmission ratio is derived from the difference in tooth counts between the oscillating teeth and the end-face gear, a hallmark of strain wave gear systems. Mathematically, the output speed \(v_2\) is given by:

$$v_2 = \frac{v_1}{i} = v_1 \frac{Z_O – Z_E}{Z_O}$$

where \(v_1\) is the input speed, \(i\) is the reduction ratio, \(Z_O\) is the theoretical number of oscillating teeth, and \(Z_E\) is the number of teeth on the end-face gear. This equation underscores the high reduction capabilities inherent to strain wave gear designs, often achieving ratios from 50:1 to 320:1 in a compact space. The negative sign in the ratio indicates a reversal in direction, which is common in such transmissions. The following table summarizes the key parameters and their typical values in this strain wave gear system:

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Speed | \(v_1\) | 240 deg/sec | Angular velocity of input shaft |

| Output Speed | \(v_2\) | ≈ -10 deg/sec | Angular velocity of output shaft |

| Oscillating Teeth Count | \(Z_O\) | 40 | Number of theoretical oscillating teeth |

| End-Face Gear Teeth Count | \(Z_E\) | 38 | Number of teeth on end-face gear |

| Reduction Ratio | \(i\) | \(Z_O / (Z_O – Z_E)\) = 20 | Gear ratio for this configuration |

| Module | \(m\) | 2 mm | Gear module size |

The design of individual components is critical for optimal performance. The wave generator, essentially an end-face cam, features a multi-start helical surface that dictates the motion of the oscillating teeth. Its profile is defined by a parametric equation to ensure precise meshing. For a strain wave gear system, the cam lobe count matches the difference in tooth counts, typically two lobes for a high reduction ratio. The profile can be expressed in cylindrical coordinates \((r, \theta, z)\) as:

$$z(\theta) = A \sin(n \theta) + B \cos(m \theta)$$

where \(A\) and \(B\) are amplitude coefficients, \(n\) is the number of lobes, and \(m\) is a modulation factor. This sinusoidal pattern generates the harmonic motion that characterizes strain wave gear operation. Similarly, the end-face gear has a conjugated profile to mesh smoothly with the oscillating teeth. Each oscillating tooth is designed as a slider with a curved contact surface, modeled using spline curves to reduce stress concentration. The slotted wheel houses these teeth in precision-machined slots, allowing axial movement while transmitting torque. Material selection is also vital; for instance, the wave generator and gears are often made from hardened steel, while the oscillating teeth use bronze or composite materials to minimize wear. The integration of these parts forms a robust strain wave gear transmission capable of handling high loads with minimal backlash.

Moving to digital modeling, I utilized Pro/ENGINEER (now Creo Parametric) for its powerful parametric and feature-based design capabilities. The 3D modeling process began with creating the wave generator. Given its complex geometry, I derived the tooth surface equations and used parametric curves to sketch the profile. For example, the helical surface was generated by sweeping a curve along a helical path, defined by:

$$x = r \cos(\theta), \quad y = r \sin(\theta), \quad z = \frac{p \theta}{2\pi}$$

where \(p\) is the pitch. This approach ensured accuracy in the strain wave gear components. The end-face gear was modeled similarly, with teeth arrayed circularly using pattern features. The oscillating teeth were created as separate parts, with their contact surfaces tailored to match both the wave generator and end-face gear. Other components, such as the slotted wheel, input shaft, output shaft, housing, and bearing covers, were modeled based on standard mechanical design principles. The slotted wheel, for instance, includes slots equally spaced at angles of \(360^\circ / Z_O\), and the housing was designed with mounting features for assembly. Below is a comparison of key components and their modeling complexity in this strain wave gear system:

| Component | Modeling Technique | Key Features | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wave Generator | Parametric surfaces, helical sweeps | Multi-lobe cam profile, high precision | Ensuring smooth curvature for meshing |

| End-Face Gear | Patterned teeth, extruded cuts | Conjugated tooth shape, durability | Maintaining tooth thickness and strength |

| Oscillating Teeth | Spline curves, lofted blends | Curved contact surfaces, low friction | Avoiding interference during motion |

| Slotted Wheel | Circular patterns, slot cuts | Precision slots, torque transmission | Aligning slots with tooth paths |

| Housing | Extrusions, shells, ribs | Rigid structure, bearing seats | Managing thermal expansion and assembly |

After modeling, the virtual assembly was conducted to ensure proper fit and function. The assembly process in Pro/ENGINEER involved defining constraints and connections between parts. For the strain wave gear transmission, I adopted a bottom-up approach, starting with sub-assemblies. The input sub-assembly included the input shaft, wave generator, bearings, and retainers, connected using pin joints to allow rotation. The output sub-assembly consisted of the output shaft, slotted wheel, oscillating teeth, and torque tube. Here, the oscillating teeth were connected to the slotted wheel with slider joints, permitting axial movement, while the slotted wheel was fixed to the output shaft with rigid connections. The overall assembly then integrated these sub-assemblies into the housing, with the end-face gears fixed to the housing. This virtual prototyping phase was crucial for identifying interferences and optimizing clearances, a common step in strain wave gear development to prevent binding or excessive play.

For motion simulation, Pro/ENGINEER’s Mechanism module was employed. This tool enables kinematic and dynamic analysis by defining joints, drivers, and force interactions. However, simulating the meshing between the wave generator and oscillating teeth—as well as between the oscillating teeth and end-face gear—posed a challenge, as these are essentially spatial cam mechanisms with multiple followers. Standard cam-follower definitions in the software were insufficient. To address this, I utilized slot-follower connections, where a point on the oscillating tooth follows a curve on the wave generator or end-face gear. This workaround effectively captured the complex motion of the strain wave gear system. The steps included:

- Creating slot-follower connections for each oscillating tooth with the wave generator’s cam profile curve.

- Creating similar slot-follower connections for each oscillating tooth with the end-face gear’s tooth profile curve.

- Defining a servo motor on the input shaft with a constant angular velocity of 240 degrees per second.

- Running a dynamic analysis over a specified time period, such as 10 seconds, to observe the motion.

The simulation revealed the engagement process, showing how the oscillating teeth move axially while pushing the slotted wheel to rotate. This visual validation is essential for confirming the strain wave gear principle in this hybrid design. The output motion was smooth, with minimal vibration, indicating good meshing characteristics. To quantify performance, I measured various kinematic parameters, as detailed below.

The dynamic analysis provided insights into velocity, acceleration, and displacement. For the output shaft, the angular velocity fluctuated slightly around -10 degrees per second, consistent with the theoretical calculation from the strain wave gear ratio formula. The angular acceleration ranged between -1.9 and 1.9 degrees per second squared, averaging near zero, which implies stable motion with minor perturbations due to meshing transitions. The oscillating teeth exhibited periodic axial velocity and acceleration profiles, with velocities peaking at ±54 inches per second and accelerations at ±23.4 inches per second squared. These values align with expectations for a strain wave gear system, where harmonic motion induces cyclic loads. The following equations summarize the relationships observed:

$$\omega_{\text{output}} = \frac{\omega_{\text{input}}}{i} + \epsilon(t)$$

where \(\epsilon(t)\) is a small periodic error function due to manufacturing tolerances. The acceleration \(a\) of an oscillating tooth can be approximated by:

$$a = -\omega^2 A \sin(\omega t + \phi)$$

with \(A\) as the amplitude of oscillation and \(\phi\) as a phase shift. These dynamics are critical for assessing fatigue life and efficiency in strain wave gear applications. To further analyze the results, I compiled key simulation outputs into a table:

| Measurement | Minimum Value | Maximum Value | Average Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Output Shaft Angular Velocity | -10.046 | -9.900 | ≈ -10.0 | deg/sec |

| Output Shaft Angular Acceleration | -1.9 | 1.9 | ≈ 0.0 | deg/sec² |

| Oscillating Tooth Axial Velocity | -54.0 | 54.0 | 0.0 (cyclic) | in/sec |

| Oscillating Tooth Axial Acceleration | -23.4 | 21.5 | 0.0 (cyclic) | in/sec² |

| Meshing Frequency | \(f = \frac{\omega_{\text{input}} \cdot Z_E}{360}\) ≈ 25.3 Hz | Hz | ||

The simulation also allowed for interference checking, confirming that no collisions occur during operation—a vital aspect for reliability in strain wave gear systems. The only contact points are the intended meshing surfaces, which reduces wear and noise. Additionally, the virtual prototype enabled evaluation of load distribution across the oscillating teeth. Since multiple teeth engage simultaneously, the stress is shared, enhancing the load capacity compared to traditional strain wave gears where the flexspline bears concentrated stress. This advantage is a key selling point for this design, as it merges the high reduction of strain wave gears with the robustness of oscillating tooth drives.

From a broader perspective, the integration of digital tools like Pro/ENGINEER has revolutionized the development of strain wave gear transmissions. Parametric modeling allows quick iterations; for instance, changing the tooth count \(Z_E\) or \(Z_O\) automatically updates all related dimensions and simulations. This flexibility is crucial for customizing strain wave gear reducers for specific applications, such as robotic joints or aerospace actuators. Moreover, the simulation data can be exported for finite element analysis (FEA) to assess structural integrity under loads. The dynamic loads derived from the kinematic analysis serve as inputs for stress simulations, ensuring the design meets safety factors. The table below contrasts this advanced strain wave gear system with conventional alternatives:

| Feature | Traditional Strain Wave Gear | Oscillating Tooth Drive | End-Face Strain Wave Gear with Oscillating Teeth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Component | Yes (flexspline) | No | No (rigid components) |

| Radial Dimensions | Compact | Large | Compact |

| Meshing Gap Adjustability | Limited | No | Yes |

| Simultaneous Meshing Teeth | Moderate (10-30%) | High (50-70%) | High (60-80%) |

| Load Capacity | Limited by flexspline | High | Very High |

| Transmission Ratio Range | 50:1 to 320:1 | 10:1 to 100:1 | 20:1 to 200:1 |

| Typical Applications | Robotics, aerospace | Heavy machinery | Robotics, industrial automation |

Looking ahead, further optimization of this strain wave gear system is possible. For example, the tooth profiles can be refined using advanced algorithms to minimize contact stress and improve efficiency. The equation for contact stress \(\sigma_c\) according to Hertzian theory is:

$$\sigma_c = \sqrt{\frac{F}{\pi \cdot b} \cdot \frac{1}{\frac{1 – \nu_1^2}{E_1} + \frac{1 – \nu_2^2}{E_2}} \cdot \frac{1}{R}}$$

where \(F\) is the load, \(b\) is the contact width, \(\nu\) is Poisson’s ratio, \(E\) is Young’s modulus, and \(R\) is the effective radius of curvature. By adjusting the profile curvature, \(\sigma_c\) can be reduced, extending the lifespan of the strain wave gear. Additionally, materials like ceramics or coatings could be explored to enhance wear resistance. Another avenue is the integration of smart sensors for real-time monitoring of wear and alignment, enabling predictive maintenance in critical applications.

In conclusion, the end-face strain wave gear transmission with oscillating teeth represents a significant advancement in gear technology. By combining the principles of strain wave gear drives with oscillating tooth mechanisms, it achieves high power density, precision, and durability. Through detailed 3D modeling, virtual assembly, and motion simulation using Pro/ENGINEER, I have validated the design and analyzed its kinematic performance. The results confirm stable operation with expected velocity and acceleration profiles, underscoring the feasibility of this strain wave gear system. Future work will focus on prototyping and experimental testing to correlate simulation data with real-world performance. As strain wave gear technology evolves, such hybrid designs promise to expand the boundaries of mechanical transmission, offering efficient solutions for modern engineering challenges. The journey from concept to virtual prototype has been enlightening, demonstrating the power of computational tools in innovating strain wave gear systems for tomorrow’s applications.

Throughout this exploration, the term “strain wave gear” has been central, highlighting its influence on the design and simulation processes. This strain wave gear approach not only improves traditional systems but also opens new possibilities for customization and integration. As I continue to refine this technology, the insights gained will contribute to the broader field of precision mechanics, where strain wave gear reducers play a pivotal role in enabling advanced motion control. The collaborative synergy between digital engineering and mechanical design ensures that strain wave gear transmissions remain at the forefront of innovation, driving progress in industries that demand reliability and efficiency.